The Growing Pains of Urbanization, 1870-1900

Explore the The Growing Pains of Urbanization, 1870-1900 study material pdf and utilize it for learning all the covered concepts as it always helps in improving the conceptual knowledge.

The Growing Pains of Urbanization, 1870-1900 PDF Download

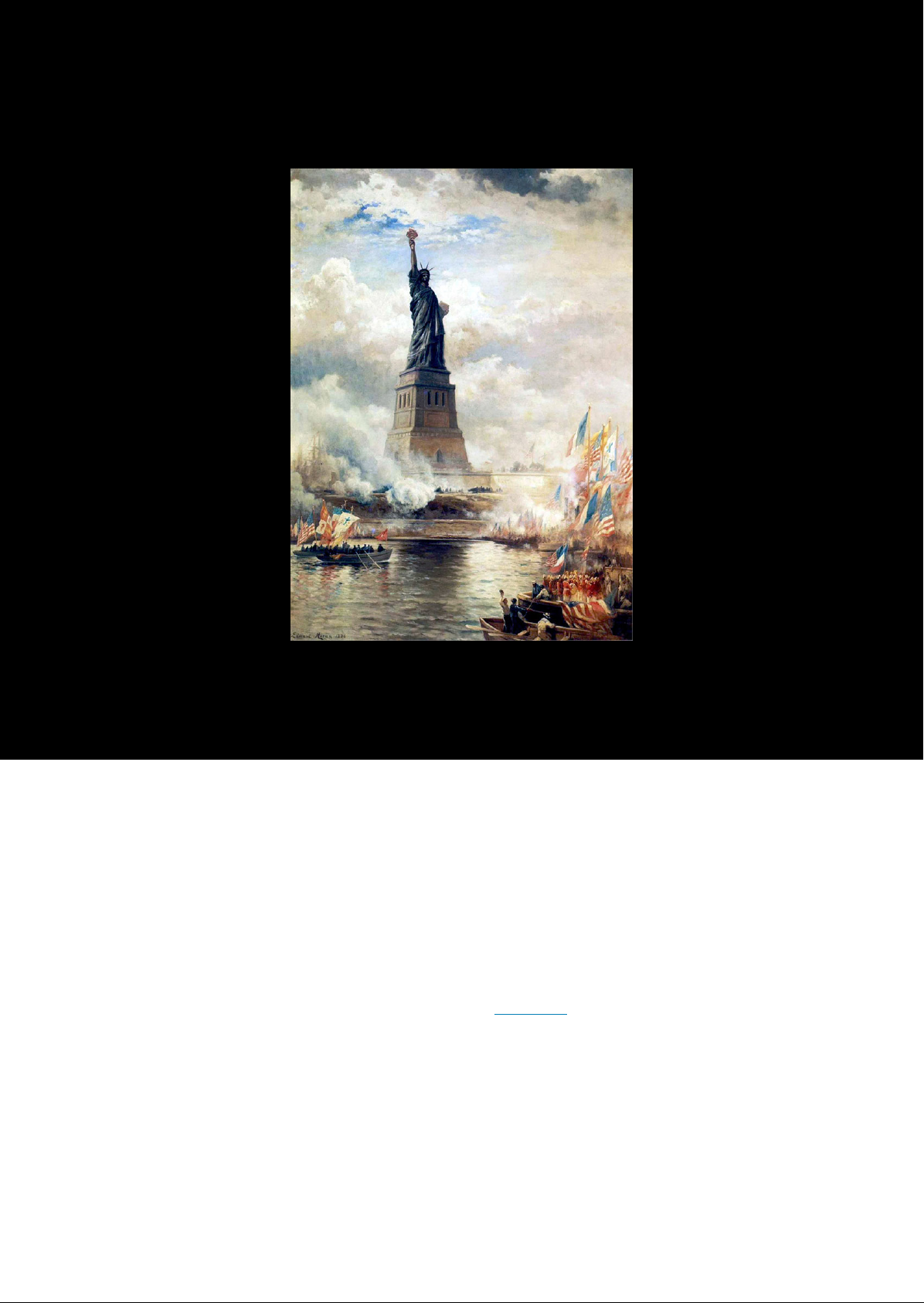

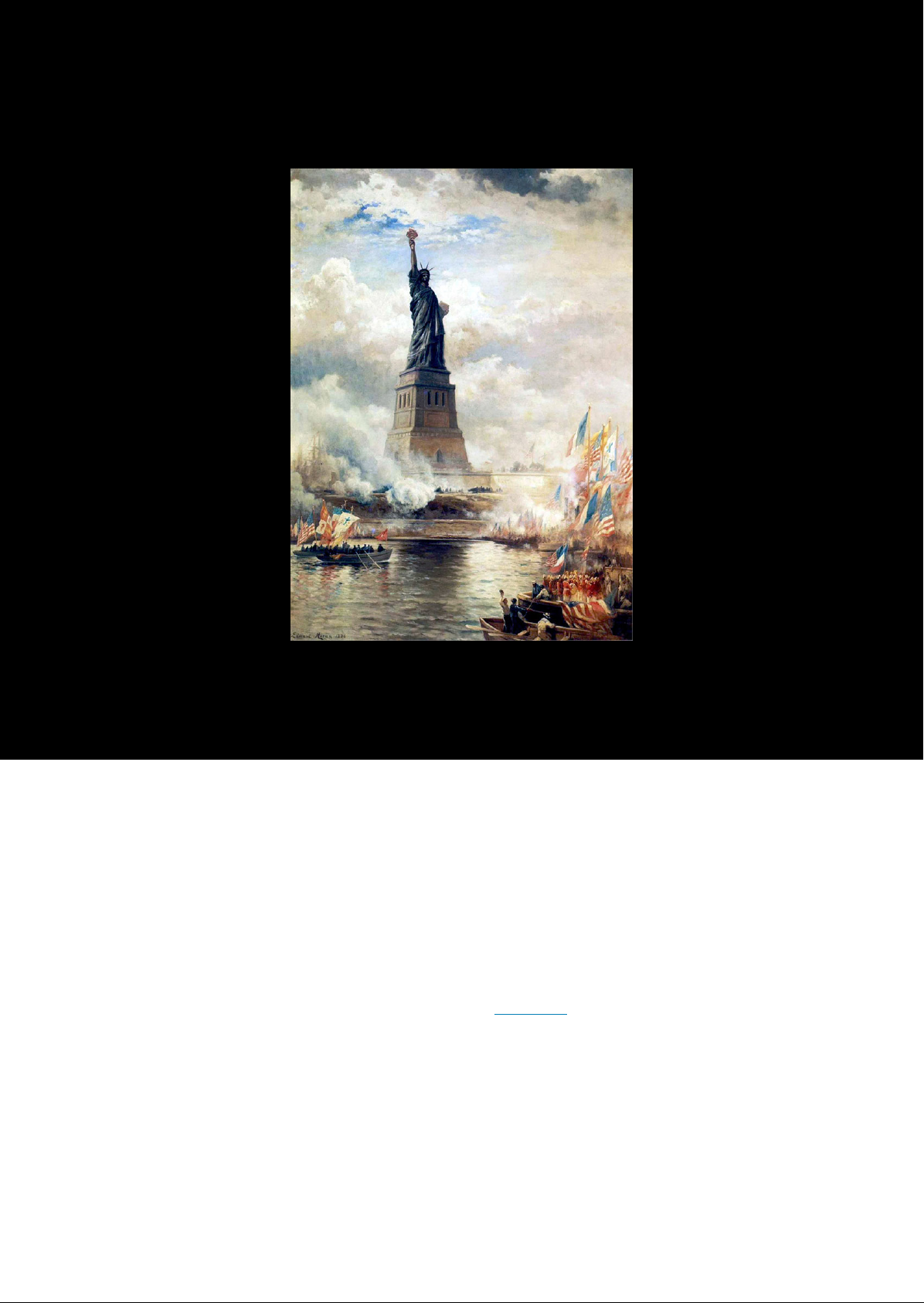

The Growing Pains of , FIGURE For the millions of immigrants arriving by ship in New York City harbor , the sight of the Statue of Liberty , as in Unveiling the Statue ( 1886 ) by Edward Moran , stood as a physical representation of the new freedoms and economic opportunities they hoped to find . CHAPTER OUTLINE Urbanization and Its Challenges The African American Great Migration and New European Immigration Relief from the Chaos of Urban Life Change Reflected in Thought and Writing INTRODUCTION We saw the big woman with spikes on her head . So begins Sadie first memory of arriving in the United States . Many Americans experienced in their new home what the Polish girl had seen in the silhouette of the Statue of Liberty a wondrous world of new opportunities fraught with dangers . Sadie and her mother , for instance , had left Poland after her father death . Her mother died shortly thereafter , and Sadie had to her own way in New York , working in factories and slowly assimilating to life in a vast multinational metropolis . Her story is similar to millions of others , as people came to the United States seeking a better future than the one they had at home . The future they found , however , was often grim . While many believed in the land of opportunity , the reality of urban life in the United States was more chaotic and difficult than people expected . In addition to the challenges of language , class , race , and ethnicity , these new arrivals dealt with low wages , overcrowded buildings , poor sanitation , and widespread disease . The land of opportunity , it seemed , did not always deliver

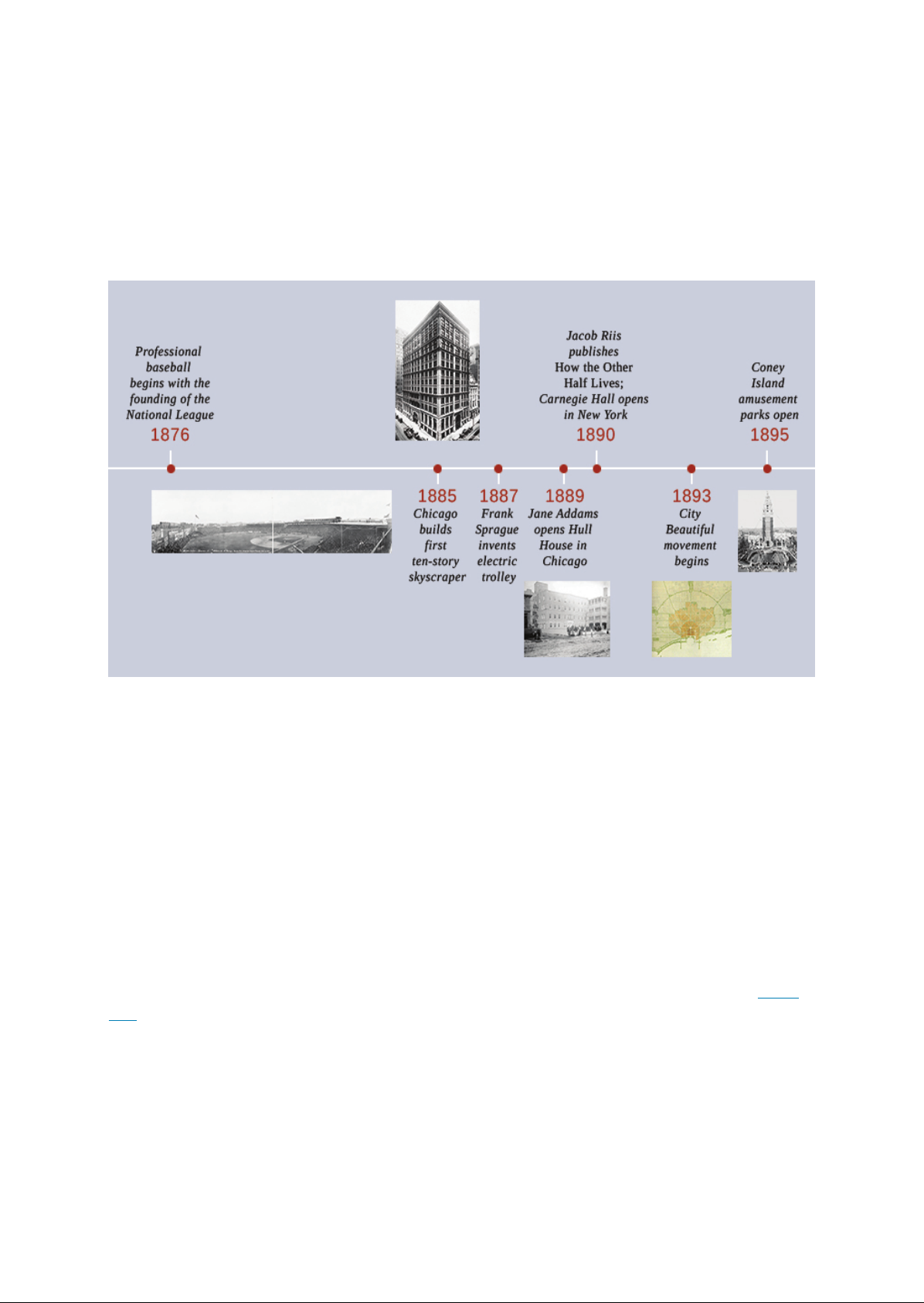

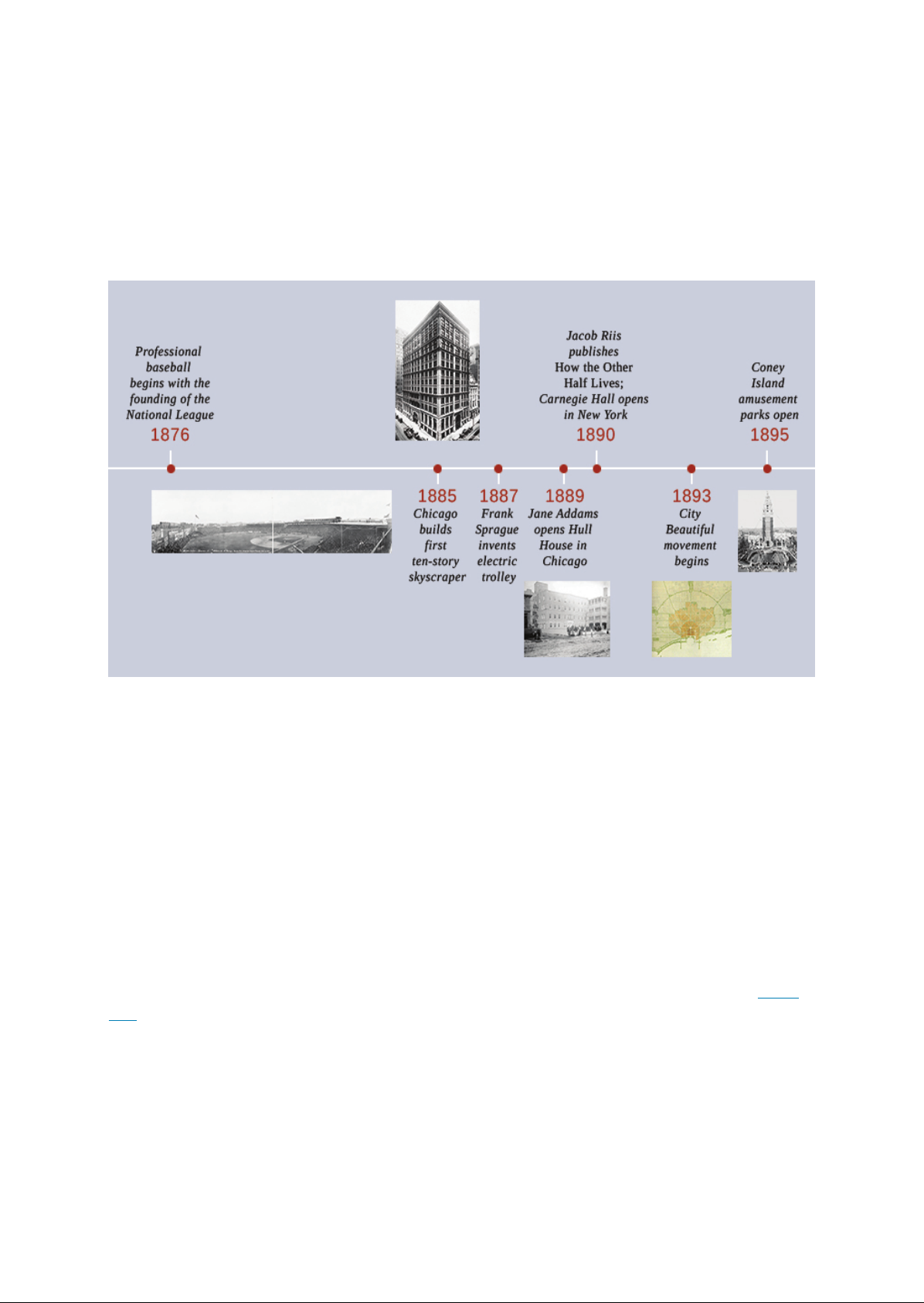

492 19 The Growing Pains of Urbanization , on its promises . Urbanization and Its Challenges LEARNING OBJECTIVES By the end ofthis section , you will be able to Explain the growth of American cities in the late nineteenth century key challenges that Americans faced due to urbanization , as well as some ofthe possible solutions to those challenges Jacob publishes baseball How the Other Coney begins with the Half Lives Island founding of the Carnegie Hall opens amusement National League in New York parks open 1876 1890 1895 1885 1887 1889 1893 Chicago Prank Jane Addams builds Sprague opens Hull Beautiful first invents House in movement electric Chicago begins skyscraper FIGURE Urbanization occurred rapidly in the second half of the nineteenth century in the United States for a number of reasons . The new technologies of the time led to a massive leap in industrialization , requiring large numbers of workers . New electric lights and powerful machinery allowed factories to run hours a day , seven days a week . Workers were forced into grueling shifts , requiring them to live close to the factories . While the work was dangerous and , many Americans were willing to leave behind the declining prospects of preindustrial agriculture in the hope of better wages in industrial labor . Furthermore , problems ranging from famine to religious persecution led a new wave of immigrants to arrive from central , eastern , and southern Europe , many of whom settled and found work near the cities where they arrived . Immigrants sought solace and comfort among others who shared the same language and customs , and the nation cities became an invaluable economic and cultural resource . Although cities such as Philadelphia , Boston , and New York sprang up from the initial days of colonial settlement , the explosion in urban population growth did not occur until the century ( Figure ) At this time , the attractions of city life , and in particular , employment opportunities , grew exponentially due to rapid changes in industrialization . Before the , factories , such as the early textile mills , had to be located near rivers and seaports , both for the transport of goods and the necessary water power Production became dependent upon seasonal water , with cold , icy winters all but stopping river transportation entirely . The development of the steam engine transformed this need , allowing businesses to locate their factories near urban centers . These factories encouraged more and more people to move to urban areas where jobs were plentiful , but hourly wages were often low and the work was routine and grindingly monotonous . Access for free at .

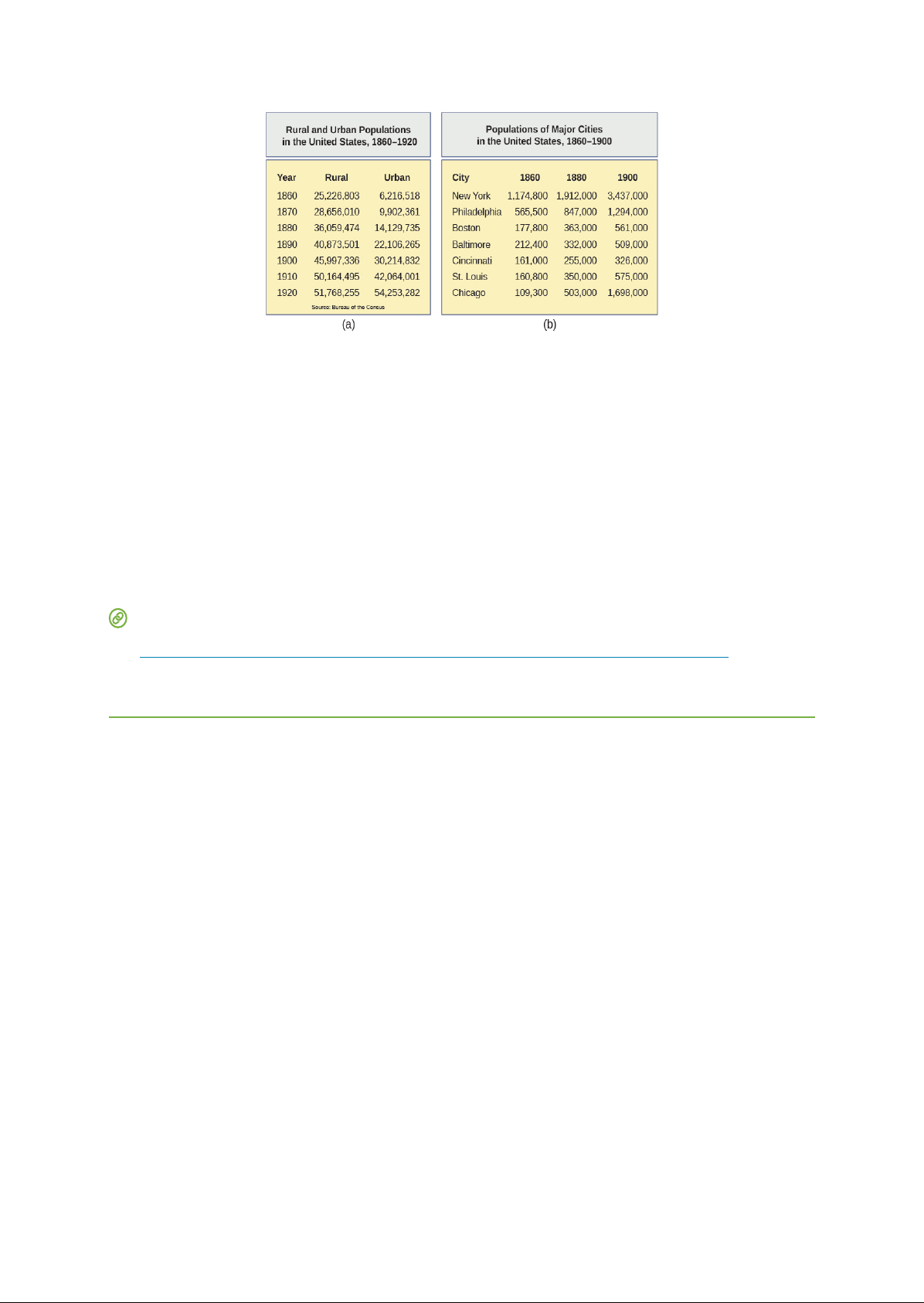

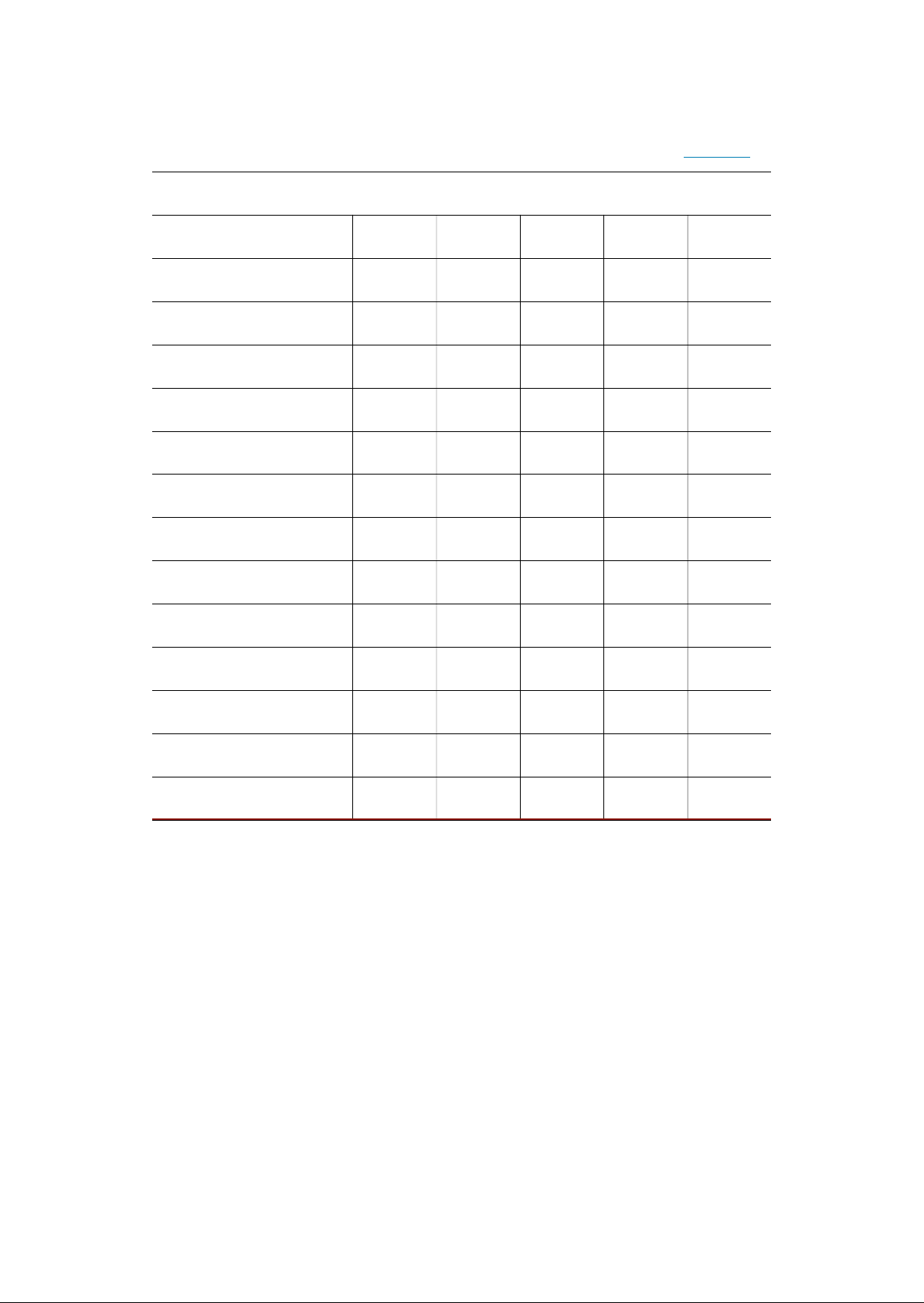

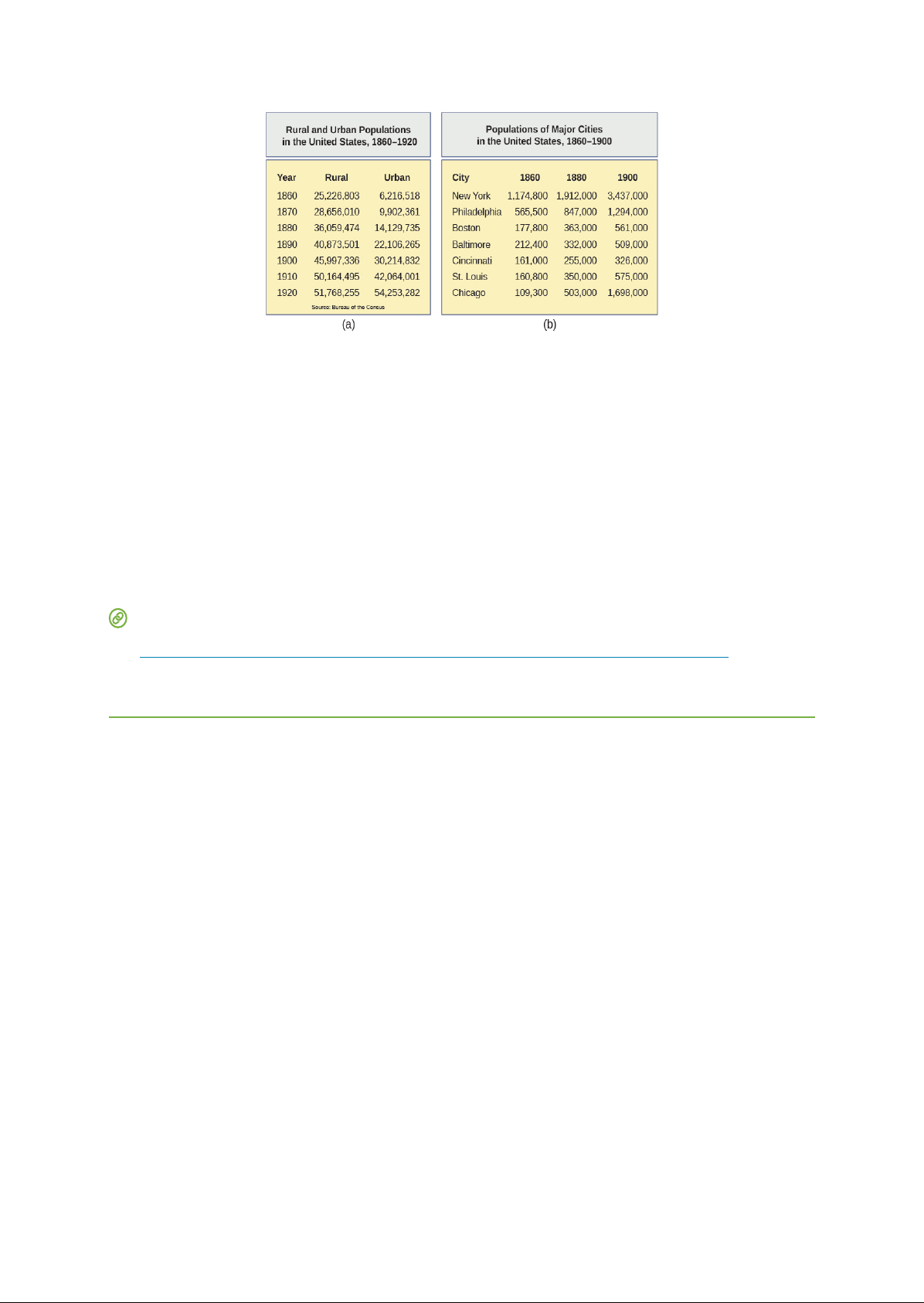

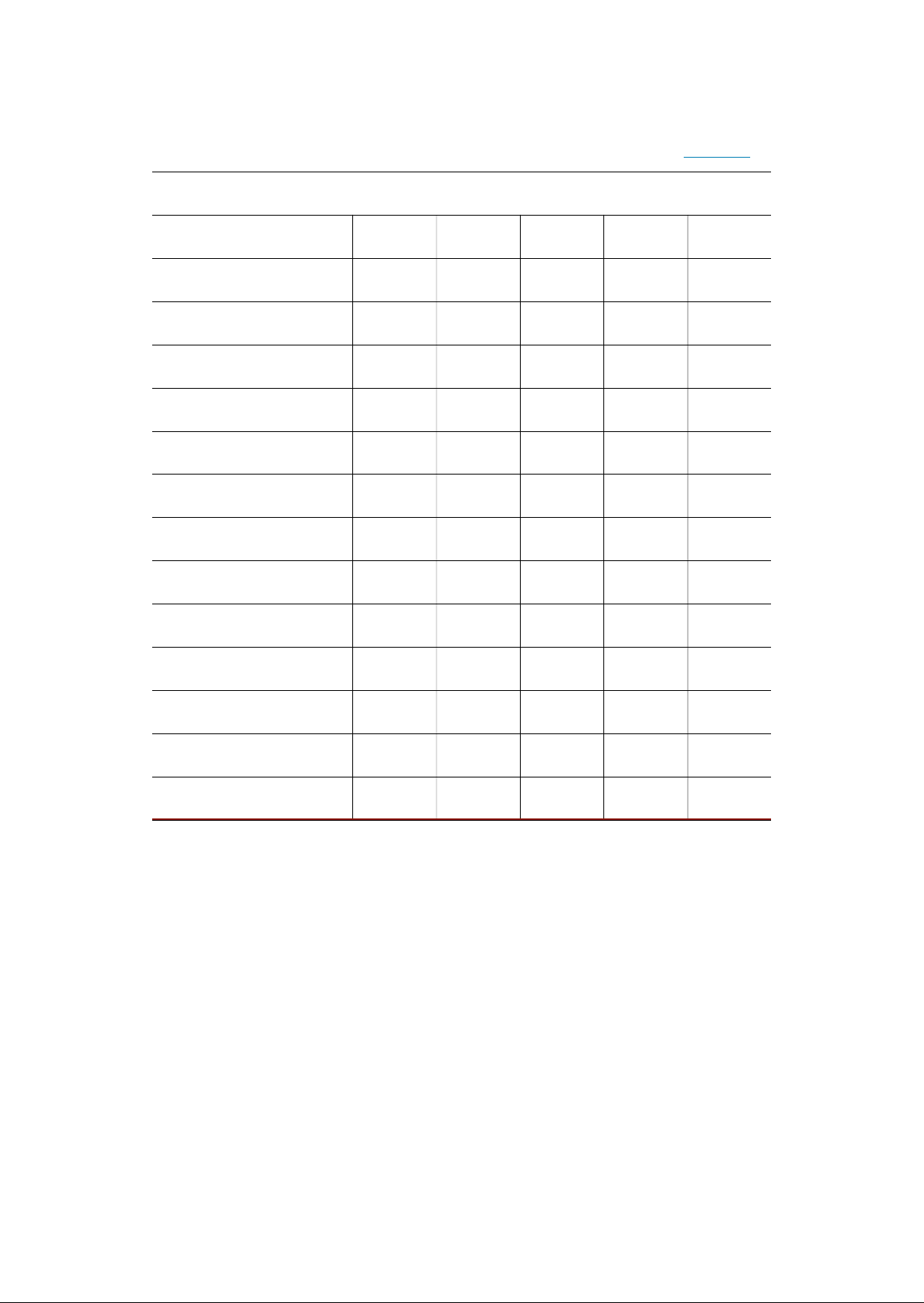

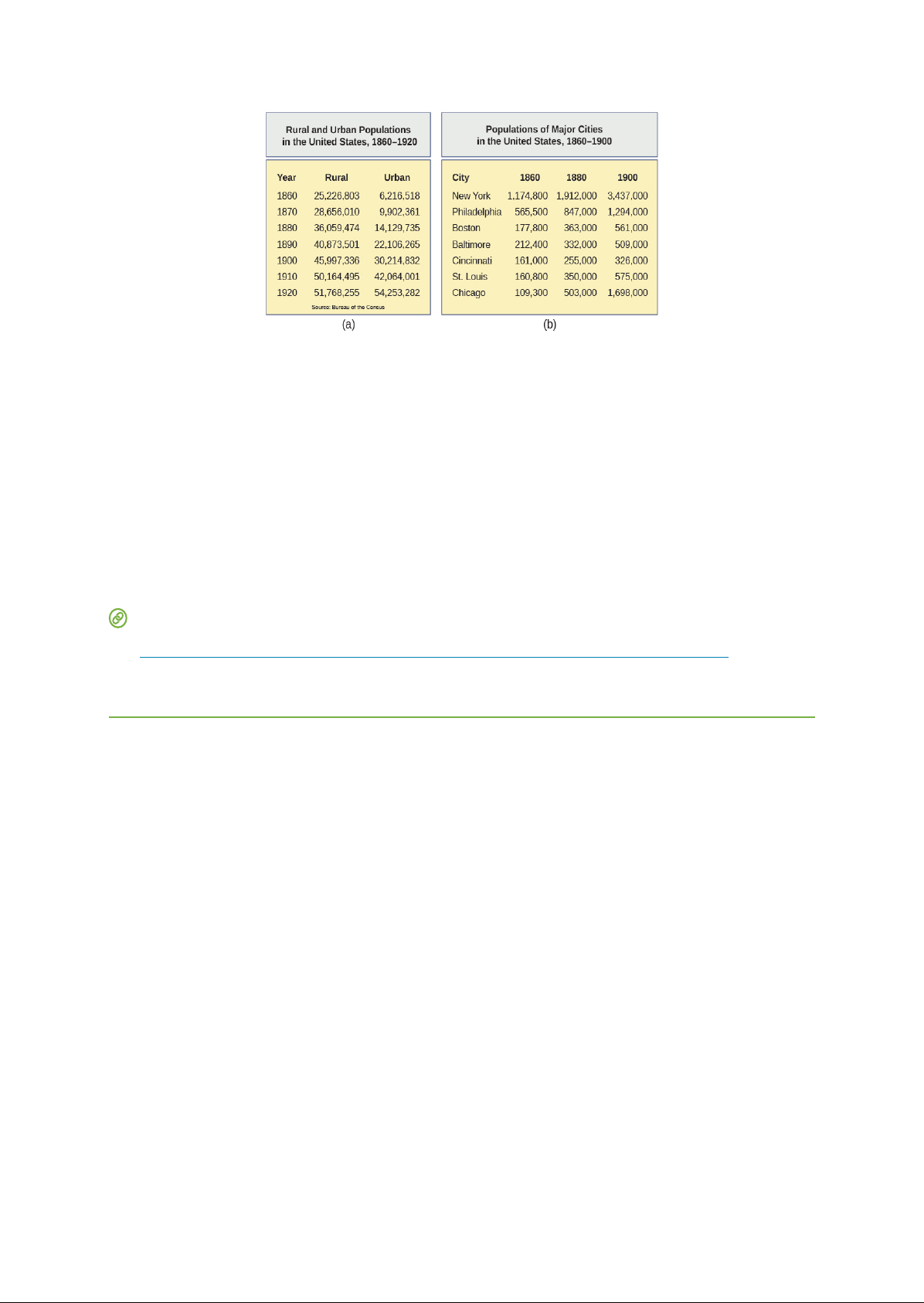

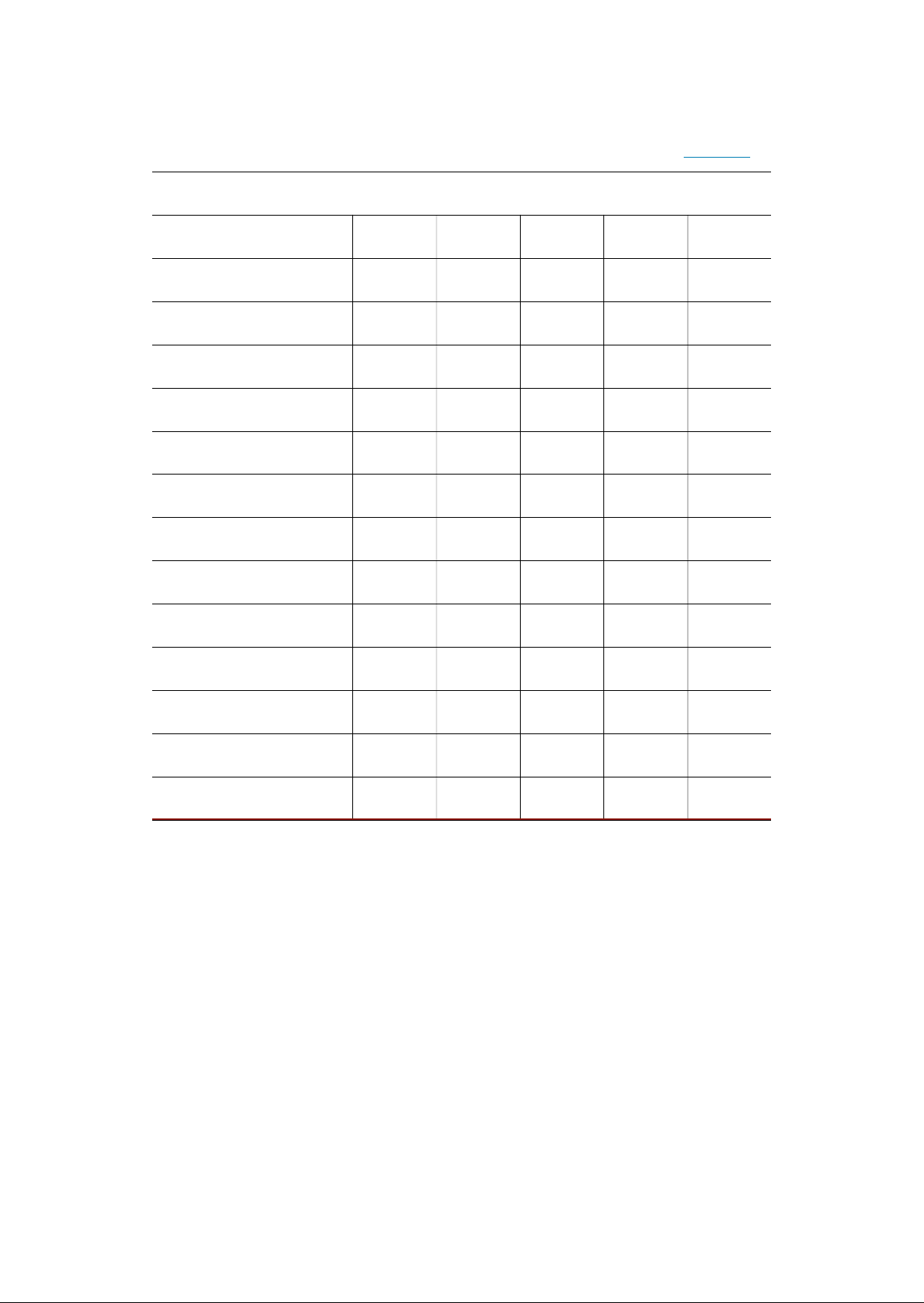

Urbanization and Its Challenges 493 Rural and Urban Populations Populations of Major Cities in the United States , in the United States , 18604900 Vear Rural Urban City 1860 1880 1900 1860 New 1870 Philadelphia 1880 Boston 1890 Baltimore 1900 Cincinnati 1910 St Louis 1920 Chicago Em , FIGURE As these panels illustrate , the population of the United States grew rapidly in the late ( a ) Much of this new growth took place in urban areas ( by the census as hundred people or more ) and this urban population , par that of major cities ( dealt with challenges and opportunities that were unknown in previous generations . Eventually , cities developed their own unique characters based on the core industry that spurred their growth . In Pittsburgh , it was steel in Chicago , it was meat packing in New York , the garment and industries dominated and Detroit , by the century , was by the automobiles it built . But all cities at this time , regardless of their industry , suffered from the universal problems that rapid expansion brought with it , including concerns over housing and living conditions , transportation , and communication . These issues were almost always rooted in deep class inequalities , shaped by racial divisions , religious differences , and ethnic strife , and distorted by corrupt local politics . CLICK AND EXPLORE This 1884 Bureau of Labor Statistics report for Massachusetts ( from Boston looks in detail at the wages , living conditions , and moral code of the girls who worked in the clothing factories there . THE KEYS SUCCESSFUL URBANIZATION As the country grew , certain elements led some towns to morph into large urban centers , while others did not . The following four innovations proved critical in shaping urbanization at the turn of the century electric lighting , communication improvements , intracity transportation , and the rise of skyscrapers . As people migrated for the new jobs , they often with the absence of basic urban infrastructures , such as better transportation , adequate housing , means of communication , and sources of light and energy . Even the basic necessities , such as fresh water and taken for granted in the a greater challenge in urban life . Electric Lighting Thomas Edison patented the incandescent lig It bulb in 1879 . This development quickly became common in homes as well as factories , transforming how even and Americans lived . Although slow to arrive in rural areas of the country , electric power became readily available in cities when the commercial power plants began to open in 1882 . When Ni cola Tesla subsequently developed the AC ( alternating current ) system for the Electric Manu Company , power supplies for lights and other factory equipment could extend for miles from the power source . AC power transformed the use of electricity , allowing urban centers to physically cover greater areas . In the factories , electric lights permitted operations to run hours a day , seven days a week . increase in production required additional workers , and this demand brought more people to cities . Gradually , cities began to illuminate the stree with electric lamps to allow the city to remain alight

494 19 The Growing Pains of Urbanization , throughout the night . No longer did the pace of life and economic activity slow substantially at sunset , the way it had in smaller towns . The cities , following the factories that drew people there , stayed open all the time . Communications Improvements The telephone , patented in 1876 , greatly transformed communication both regionally and nationally . The telephone rapidly supplanted the telegraph as the preferred form of communication by 1900 , over million telephones were in use around the nation , whether as private lines in the homes of some and class Americans , or as jointly used party lines in many rural areas . By allowing instant communication over larger distances at any given time , growing telephone networks made urban sprawl possible . In the same way that electric lights spurred greater factory production and economic growth , the telephone increased business through the more rapid pace of demand . Now , orders could come constantly via telephone , rather than via . More orders generated greater production , which in turn required still more workers . This demand for additional labor played a key role in urban growth , as expanding companies sought workers to handle the increasing consumer demand for their products . Intracity Transportation As cities grew and sprawled outward , a major challenge was travel within the home to factories or shops , and then back again . Most transportation infrastructure was used to connect cities to each other , typically by rail or canal . Prior to the , two of the most common forms of transportation within cities were the omnibus and the horse car . An omnibus was a large , carriage . A horse car was similar to an omnibus , but it was placed on iron or steel tracks to provide a smoother ride . While these driven vehicles worked adequately in smaller , cities , they were not equipped to handle the larger crowds that developed at the close of the century . The horses had to stop and rest , and horse manure became an ongoing problem . In 1887 , Frank Sprague invented the electric trolley , which worked along the same concept as the horse car , with a large wagon on tracks , but was powered by electricity rather than horses . The electric trolley could run throughout the day and night , like the factories and the workers who fueled them . But it also modernized less important industrial centers , such as the southern city of Richmond , Virginia . As early as 1873 , San Francisco engineers adopted pulley technology from the mining industry to introduce cable cars and turn the city steep hills into elegant communities . However , as crowds continued to grow in the largest cities , such as Chicago and New York , trolleys were unable to move efficiently through the crowds of pedestrians ( To avoid this challenge , city planners elevated the trolley lines above the streets , creating elevated trains , or , as early as 1868 in New York City , and quickly spreading to Boston in 1887 and Chicago in 1892 . Finally , as skyscrapers began to dominate the air , transportation evolved one step further to move underground as subways . Boston subway system began operating in 1897 , and was quickly followed by New York and other cities . Access for free at .

Urbanization and Its Challenges 495 FIGURE Although trolleys were far more than carriages , populous cities such as New York experienced frequent accidents , as depicted in this 1895 illustration from Leslie Weekly ( a ) To avoid overcrowded streets , trolleys soon went underground , as at the Public Gardens Portal in Boston ( where three different lines met to enter the Street Subway , the oldest subway tunnel in the United States , opening on September . The Rise of Skyscrapers The last limitation that large cities had to overcome was the need for space . Eastern cities , unlike their midwestern counterparts , could not continue to grow outward , as the land surrounding them was already settled . Geographic limitations such as rivers or the coast also hampered sprawl . And in all cities , citizens needed to be close enough to urban centers to conveniently access work , shops , and other core institutions of urban life . The increasing cost of real estate made upward growth attractive , and so did the prestige that towering buildings carried for the businesses that occupied them . Workers completed the skyscraper in Chicago , the Home Insurance Building , in 1885 Figure . Although engineers had the capability to go higher , thanks to new steel construction techniques , they required another vital invention in order to make taller buildings viable the elevator . In 1889 , the Otis Elevator Company , led by inventor Elisha Otis , installed the electric elevator . This began the skyscraper craze , allowing developers in eastern cities to build and market prestigious real estate in the hearts of crowded eastern .

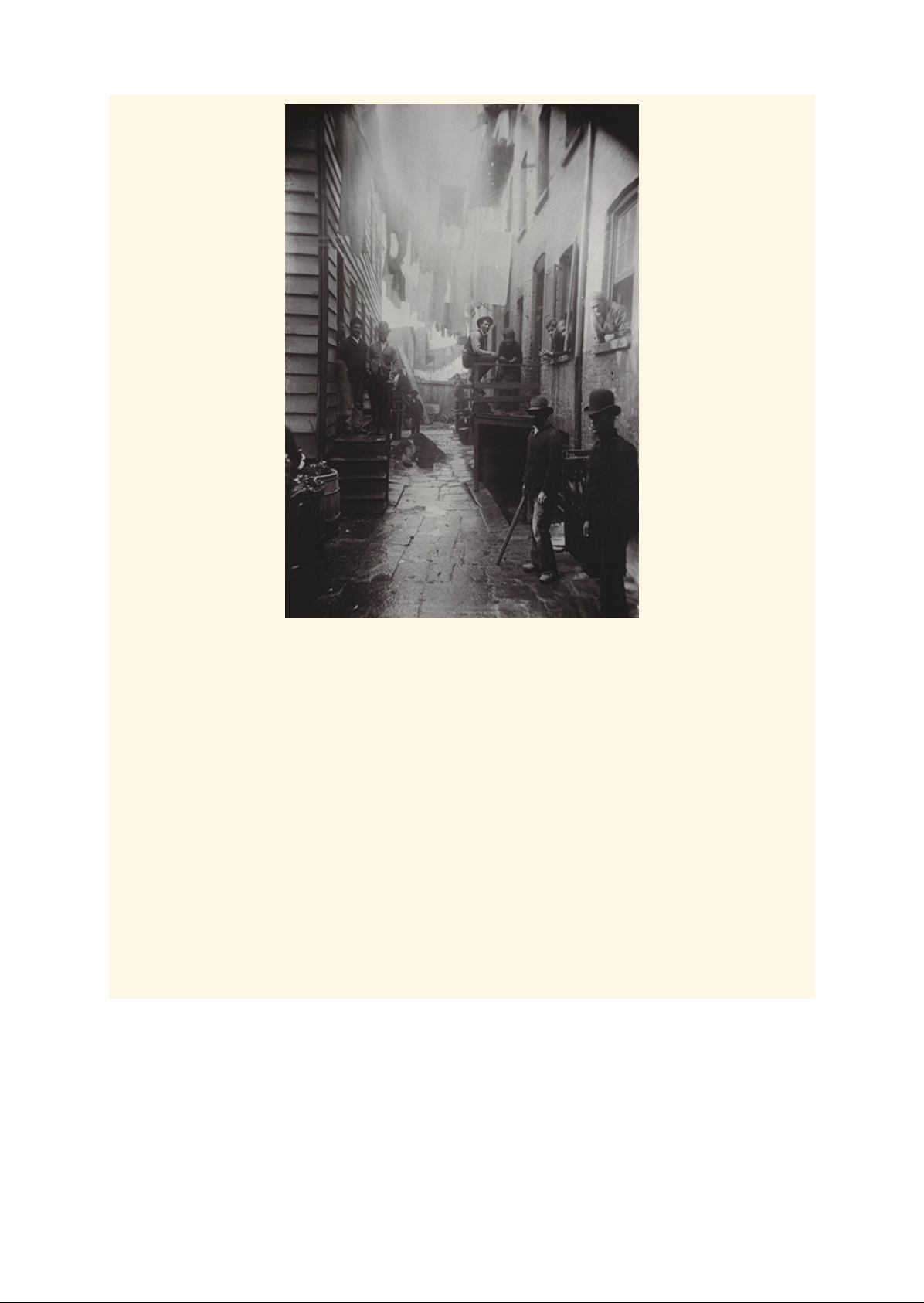

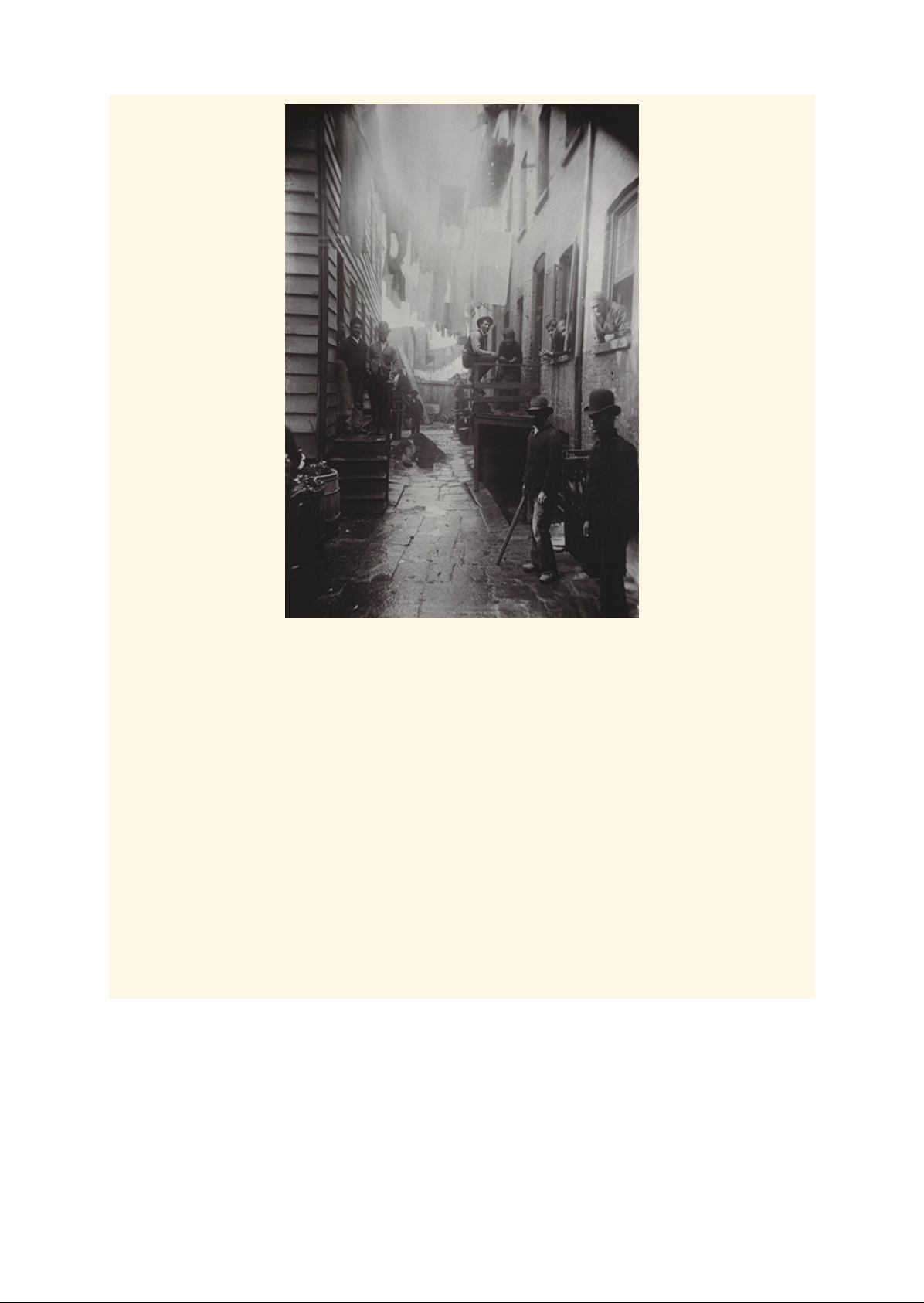

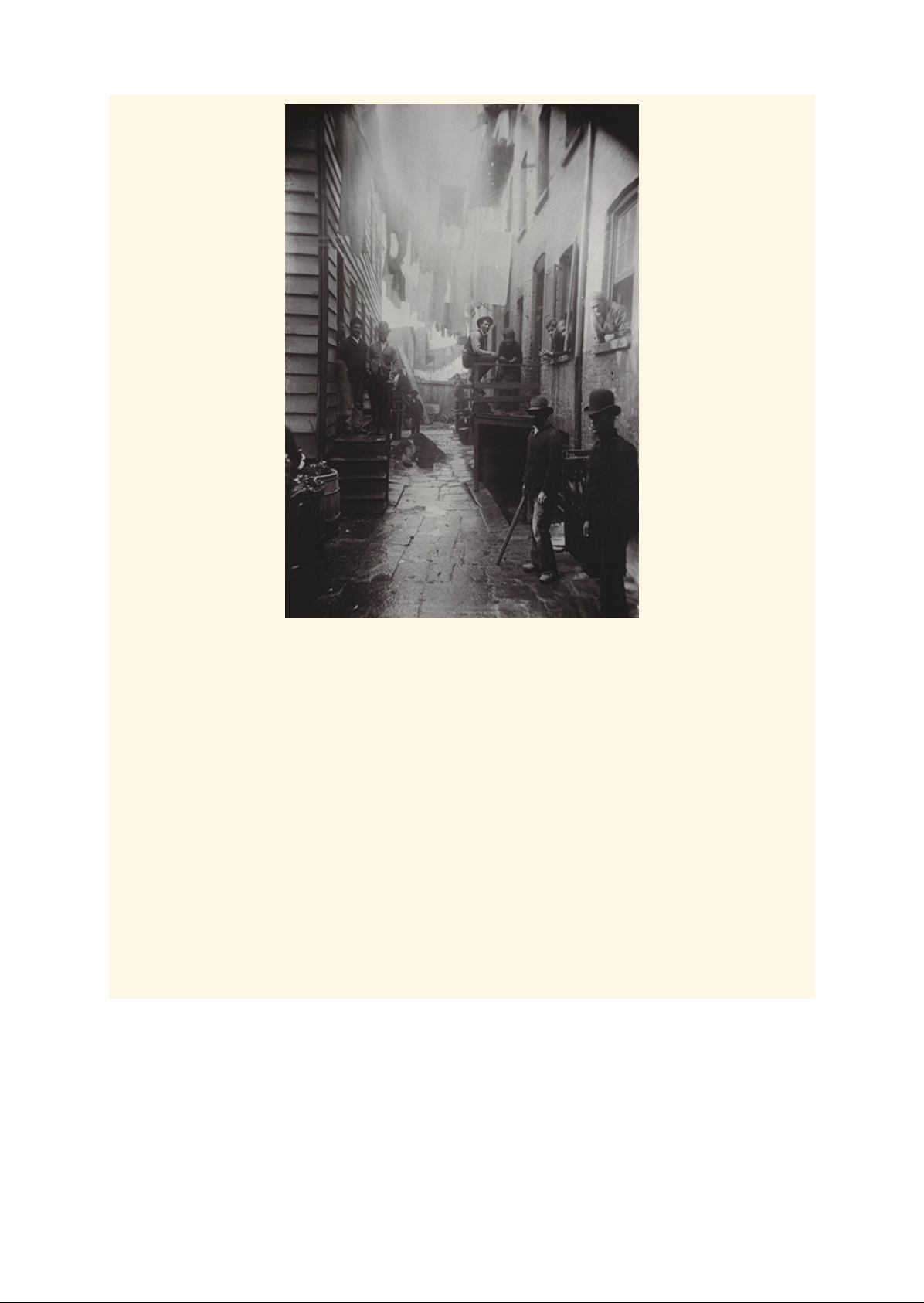

496 19 The Growing Pains of Urbanization , I . FIGURE While the technology existed to engineer tall buildings , it was not until the invention of the electric elevator in 1889 that skyscrapers began to take overthe urban landscape . Shown here is the Home Insurance Building in Chicago , considered the modern skyscraper . DEFINING AMERICAN Jacob and the Window into How the Other Half Lives Jacob was a Danish immigrant who moved to New York in the late nineteenth century and , after experiencing poverty and joblessness , ultimately built a career as a police reporter . In the course of his work , he spent much of his time in the slums and tenements of New York working poor . Appalled by what he found there , began scenes of squalor and sharing them through lectures and ultimately through the publication of his book , How the Other , in 1890 ( Figure ) Access for free at .

Urbanization and Its Challenges 497 FIGURE In photographs such as Bandit Roost ( 1888 ) taken on Mulberry Street in the infamous Five Points neighborhood of Manhattan Lower East Side , Jacob documented the plight of New York City slums in the late nineteenth century . By most contemporary accounts , was an effective storyteller , using drama and racial stereotypes to tell his stories of the ethnic slums he encountered . But while his racial thinking was very much a product of his time , he was also a reformer he felt strongly that upper and Americans could and should care about the living conditions ofthe poor . In his book and lectures , he argued against the immoral landlords and useless laws that allowed dangerous living conditions and high rents . He also suggested remodeling or building new ones . He was not alone in his concern forthe plight ofthe poor other reporters and activists had already brought the issue into the public eye , and photographs added a new element to the story . To tell his stories , used a series of deeply compelling photographs . and his group of amateur photographers moved through the various slums of New York , laboriously setting up their tripods and explosive chemicals to create enough light to take the photographs . His photos and writings shocked the public , made a both in his day and beyond , and eventually led to new state legislation curbing abuses in tenements . THE IMMEDIATE CHALLENGES OF URBAN LIFE Congestion , pollution , crime , and disease were prevalent problems in all urban centers city planners and inhabitants alike sought new solutions to the problems caused by rapid urban growth . Living conditions for most urban dwellers were atrocious . They lived in crowded tenement houses and cramped apartments with terrible ventilation and substandard plumbing and sanitation . As a result , disease ran rampant , with typhoid and cholera common . Memphis , Tennessee , experienced waves of cholera ( 1873 ) followed by yellow fever ( 1878 and 1879 ) that resulted in the loss of over ten thousand lives . By the late , New York City , Baltimore , Chicago , and New Orleans had all introduced sewage pumping systems to provide

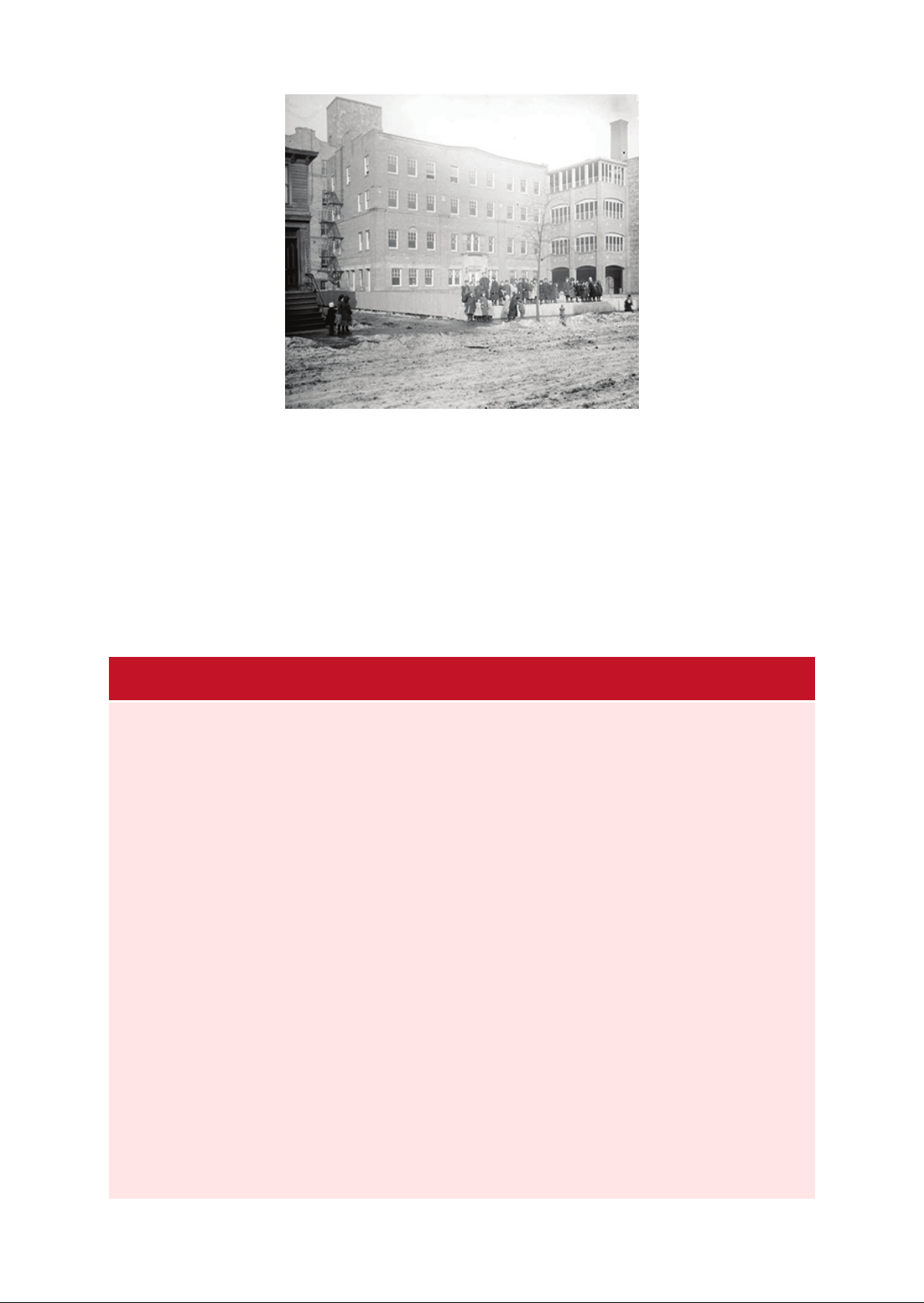

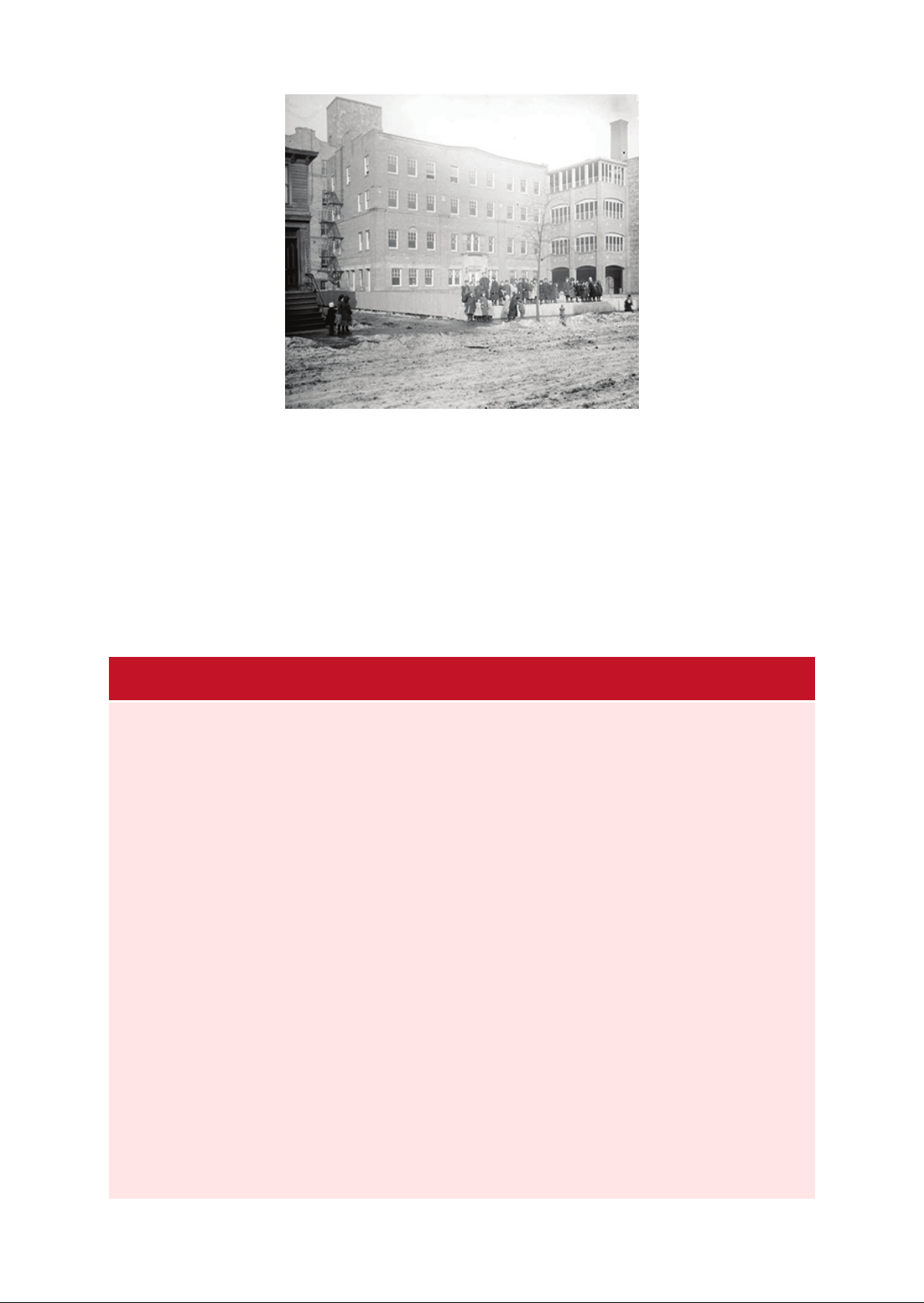

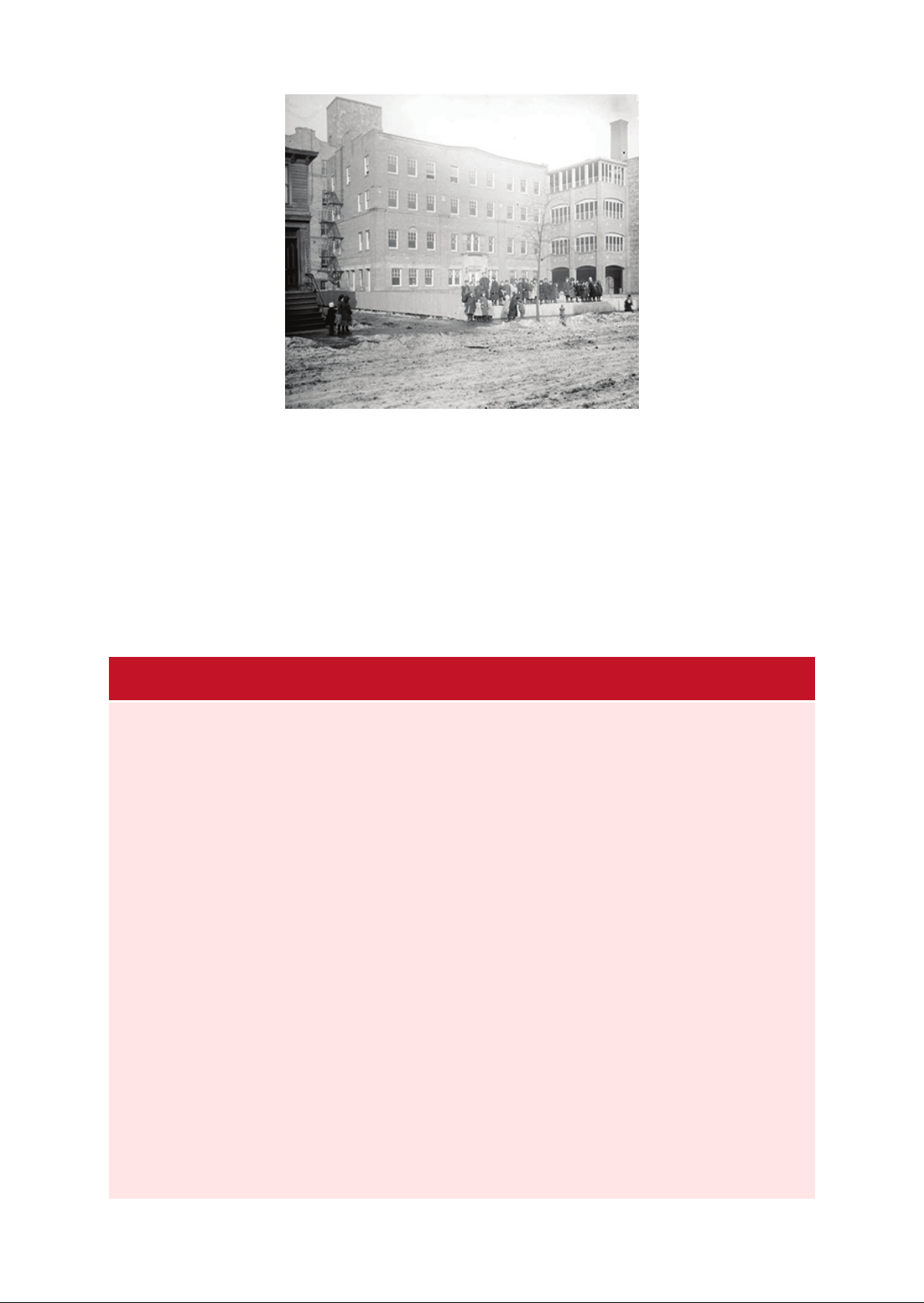

498 19 The Growing Pains of Urbanization , waste management . Many cities were also serious hazards . An average family of six , with two adults and four children , had at best a tenement . By one 1900 estimate , in the New York City borough of Manhattan alone , there were nearly thousand tenement houses . The photographs of these tenement houses are seen in Jacob book , How the Other , discussed in the feature above . Citing a study by the New York State Assembly at this time , found New York to be the most densely populated city in the world , with as many as eight hundred residents per square acre in the Lower East Side slums , comprising the Eleventh and Thirteenth Wards . CLICK AND EXPLORE Visit New York Tenement Life ( tenement ) to get an impression of the everyday life of tenement dwellers on Manhattan Lower East Side . Churches and civic organizations provided some relief to the challenges of city life . Churches were moved to intervene through their belief in the concept of the social gospel . This philosophy stated that all Christians , whether they were church leaders or social reformers , should be as concerned about the conditions of life in the secular world as the afterlife , and the Reverend Washington Gladden was a major advocate . Rather than preaching sermons on heaven and hell , Gladden talked about social changes of the time , urging other preachers to follow his lead . He advocated for improvements in daily life and encouraged Americans of all classes to work together for the betterment of society . His sermons included the message to love thy neighbor and held that all Americans had to work together help the masses . As a result of his , churches began to include gymnasiums and libraries as wel as offer evening classes on hygiene and health care . Other religious organizations like the Salvation Army and the Young Men Christian Association ( YMCA ) expanded their reach in American cities at this time as well . Beginning in the , these organizations began providing community services and other to urban poor . In the secular sphere , the settlement house movement of the 18905 provided additional relief . Pioneering women such as Jane Addams in Chicago and Lillian Wald in New York led this early progressive reform movement in the United States , building upon ideas ly fashioned by social reformers in England . With no particular religious bent , they worked to create settlement houses in urban centers where they could help the working class , and in particular , women , ind aid . Their help included child daycare , evening classes , libraries , gym facilities , and free health care . Addams opened her Hull House Figure ) in Chicago in 1889 , and Wald Henry Street Settlement opened in New York six years later . The movement spread quickly to other cities , where they not on provided relief to women but also offered employment opportunities for women graduating college in the growing of social work . Oftentimes , living in the settlement houses among the women they helped , these college graduates experienced the equivalent of living social classrooms in which to practice their skills , which also frequently caused friction with immigrant women who had their own ideas of reform and . Access for free at .

Urbanization and Its Challenges 499 . FIGURE Jane Addams opened Hull House in Chicago in 1889 , offering services and support to the city working poor . The success of the settlement house movement later became the basis of a political agenda that included pressure for housing laws , child labor laws , and workers compensation laws , among others . Florence Kelley , who originally worked with Addams in Chicago , later joined Wald efforts in New York together , they created the National Child Labor Committee and advocated for the subsequent creation of the Children Bureau in the Department of Labor in 1912 . Julia former resident of Hull the woman to head a federal government agency , when President William Howard Taft appointed her to run the bureau . Settlement house workers also became leaders in the women suffrage movement as well as the antiwar movement during World War . MY STORY Jane Addams Reflects on the Settlement House Movement Jane Addams was a social activist whose work took many forms . She is perhaps best known as the founder of Hull House in Chicago , which later became a model for settlement houses throughout the country . Here , she reflects on the role that the settlement played . Life in the Settlement discovers above all what has been called the extraordinary pliability of human nature , and it seems impossible to set any bounds to the moral capabilities which might unfold under ideal civic and educational conditions . But in order to obtain these conditions , the Settlement recognizes the need of cooperation , both with the radical and the conservative , and from the very nature of the case the Settlement can not limit its friends to any one political party or economic school . The Settlement casts side none of those things which cultivated men have come to consider reasonable and goodly , but it insists that those belong as well to that great body of people who , because of toilsome and underpaid labor , are unable to procure them for themselves . Added to this is a profound conviction that the common stock of intellectual enjoyment should not be difficult of access because ofthe economic position of him who would approach it , that those best results of civilization upon which depend the and freer aspects of living must be incorporated into our common life and have free mobility through all elements of society if we would have our democracy endure . The educational activities of a Settlement , as well its philanthropic , civic , and social undertakings , are but differing manifestations of the attempt to socialize democracy , as is the very existence of the Settlement In addition to her pioneering work in the settlement house movement , Addams also was active in the suffrage movement as well as an outspoken proponent for international peace efforts . She was instrumental in the relief effort after World War I , a commitment that led to her Nobel Peace Prize in 1931 .

500 19 The Growing Pains of Urbanization , The African American Great Migration and New European Immigration LEARNING OBJECTIVES By the end ofthis section , you will be able to factors that prompted African American and European immigration to American cities in the late nineteenth century Explain the discrimination and legislation that immigrants faced in the late nineteenth century New cities were populated with diverse waves of new arrivals , who came to the cities to seek work in the businesses and factories there . While a small percentage of these newcomers were White Americans seeking jobs , most were made up of two groups that had not previously been factors in the urbanization movement African Americans the racism of the farms and former plantations in the South , and southern and eastern European immigrants . These new immigrants supplanted the previous waves of northern and western European immigrants , who had tended to move west to purchase land . Unlike their predecessors , the newer immigrants lacked the funds to strike out to the western lands and instead remained in the urban centers where they arrived , seeking any work that would keep them alive . THE AFRICAN AMERICAN GREAT MIGRATION Between the end of the Civil War and the beginning of the Great Depression , nearly two million African Americans the rural South to seek new opportunities elsewhere . While some moved west , the vast majority of this Great Migration , as the large exodus of African Americans leaving the South in the early twentieth century was called , traveled to the Northeast and Upper Midwest . The ollowing cities were the primary destinations for these African Americans New York , Chicago , Louis , Detroit , Pittsburgh , Cleveland , and Indianapolis . These eight cities accounted for over of the total population of the African American migration . A combination of both push and pull factors played a role in this movement . Despite the end of the Civil War and the passage of the Thirteenth , Fourteenth , and Fifteenth Amendments to the Constitution ( ending slavery , ensuring equal protection under the law , and protecting the right to vote , respectively ) African Americans were still subjected to intense racial hatred . The rise of the Ku Klux an in the immediate aftermath of the Civil War led to increased death threats , violence , and a wave of . Even after the formal dismantling of the Klan in the late , racially motivated violence continued . According to researchers at the Tuskegee Institute , there were hundred racially lynchings and other murders committed in the South between 1865 and 1900 . For African Americans this culture of violence , northern and midwestern cities offered an opportunity to escape the dangers of the South . In addition to this push out of the South , African Americans were also pulled the cities by factors that attracted them , including job opportunities , where they could earn a wage rather than be tied to a landlord , and the chance to vote ( for men , at least ) supposedly free from the threat of violence . Although many lacked the funds to move themselves north , factory owners and other businesses that sought cheap labor assisted the migration . Often , the men moved then sent for their families once they were ensconced in their new city life . Racism and a lack of formal education relegated these African American workers to many of the paying unskilled or occupations . More than 80 percent of African American men worked menial jobs in steel mills , mines , construction , and meat packing . In the railroad industry , they were often employed as porters or servants ( Figure . In other businesses , they worked as janitors , waiters , or cooks . African American women , who faced discrimination due to both their race and gender , found a few job opportunities in the garment industry or laundries , but were more often employed as maids and domestic servants . Regardless of the status of their jobs , however , African Americans earned higher wages in the North than they did for the same occupations in the South , and typically found housing to be more available . Access for free at .

The African American Great Migration and New European Immigration DINING cuts ( FIGURE African American men who moved north as part of the Great Migration were often consigned to menial employment , such as working in construction or as porters on the railways ( a ) such as in the celebrated Pullman dining and sleeping cars ( However , such economic gains were offset by the higher cost of living in the North , especially in terms of rent , food costs , and other essentials . As a result , African Americans often found themselves living in overcrowded , unsanitary conditions , much like the tenement slums in which European immigrants lived in the cities . For newly arrived African Americans , even those who sought out the cities for the opportunities they provided , life in these urban centers was exceedingly . They quickly learned that racial discrimination did not end at the Line , but continued to in the North as well as the South . European immigrants , also seeking a better life in the cities of the United States , resented the arrival of the African Americans , whom they feared would compete for the same jobs or offer to work at lower wages . Landlords frequently discriminated against them their rapid into the cities created severe housing shortages and even more overcrowded tenements . Homeowners in traditionally White neighborhoods later entered into covenants in which they agreed not to sell to African American buyers they also often neighborhoods into which African Americans had gained successful entry . In addition , some bankers practiced mortgage discrimination , later known as redlining , in order to deny home loans to buyers . Such pervasive discrimination led to a concentration of African Americans in some of the worst slum areas of most major metropolitan cities , a problem that remained ongoing throughout most of the twentieth century . So why move to the North , given that the economic challenges they faced were similar to those that African Americans encountered in the South ?

The answer lies in noneconomic gains . Greater educational opportunities and more expansive personal freedoms mattered greatly to the African Americans who made the trek northward during the Great Migration . State legislatures and local school districts allocated more funds for the education of both Black and White people in the North , and also enforced compulsory school attendance laws more rigorously . Similarly , unlike the South where a simple gesture ( or lack of a deferential one ) could result in physical harm to the African American who committed it , life in larger , crowded northern urban centers permitted a degree of with it , personal enabled African Americans to move , work , and speak without deferring to every White person with whom they crossed paths . Psychologically , these gains more than offset the continued economic challenges that Black migrants faced . THE CHANGING NATURE OF EUROPEAN IMMIGRATION Immigrants also shifted the demographics of the rapidly growing cities . Although immigration had always 501

502 19 The Growing Pains of Urbanization , been a force of change in the United States , it took on a new character in the late nineteenth century . Beginning in the 18805 , the arrival of immigrants from mostly southern and eastern European countries rapidly increased while the from northern and western Europe remained relatively constant ( Table . Region Country 1870 1880 1890 1900 1910 Germany Ireland England Sweden Austria Norway Scotland Southern and Eastern Europe Italy Russia Poland Hungary Czechoslovakia TABLE Cumulative Total of the Population in the United States , by major country of birth and European region ) The previous waves of immigrants from northern and western Europe , particularly Germany , Great Britain , and the Nordic countries , were relatively well off , arriving in the country with some funds and often moving to the newly settled western territories . In contrast , the newer immigrants from southern and eastern European countries , including Italy , Greece , and several Slavic countries including Russia , came over due to push and pull factors similar to those that the African Americans arriving from the South . Many were pushed from their countries by a series of ongoing famines , by the need to escape religious , political , or racial persecution , or by the desire to avoid compulsory military service . They were also pulled by the promise of consistent , work . Whatever the reason , these immigrants arrived without the education and of the earlier waves of immigrants , and settled more readily in the port towns where they arrived , rather than setting out to seek their fortunes in the West . By 1890 , over 80 percent of the population of New York would be either or children of parentage . Other cities saw huge spikes in foreign populations as well , though not to the same degree , due in large part to Ellis Island in New York City being the primary port of entry for most Access for free at .

The African American Great Migration and New European Immigration European immigrants arriving in the United States . The number of immigrants peaked between 1900 and 1910 , when over nine million people arrived in the United States . To assist in the processing and management of this massive wave of immigrants , the Bureau of Immigration in New York City , which had become the port of entry , opened Ellis Island in 1892 . Today , nearly half of all Americans have ancestors who , at some point in time , entered the country through the portal at Ellis Island . Doctors or nurses inspected the immigrants upon arrival , looking for any signs of infectious diseases ( Figure . Most immigrants were admitted to the country with only a cursory glance at any other paperwork . Roughly percent of the arriving immigrants were denied entry due to a medical condition or criminal history . The rest would enter the country by way of the streets of New York , many unable to speak English and totally reliant on those who spoke their native tongue . FIGURE This photo shows newly arrived immigrants at Ellis Island in New York . Inspectors are examining hem for contagious health problems , which could require them to be sent back . credit ) Seeking comfort in a strange land , as well as a common language , many immigrants sought out relatives , riends , former neighbors , townspeople , and countrymen who had already settled in American cities . This led a rise in ethnic enclaves within the larger city . Little Italy , Chinatown , and many other communities developed in which immigrant groups could everything to remind them of home , from local language newspapers to ethnic food stores . While these enclaves provided a sense of community to their members , they added to the problems of urban congestion , particularly in the poorest slums where immigrants could afford musing . CLICK AND EXPLORE This Library of Congress exhibit on the history ( org ) to he United States illustrates the ongoing challenge immigrants felt between the ties to their old land and a love or America . The demographic shift at the turn of the century was later by the Commission , created Congress in 1907 to report on the nature of immigration in America the commission reinforced this ethnic of immigrants and their simultaneous discrimination . The report put it simply These newer immigrants looked and acted differently . They had darker skin tone , spoke languages with which most Americans were unfamiliar , and practiced unfamiliar religions , Judaism and Catholicism . Even the foods they sought out at butchers and grocery stores set immigrants apart . Because of these easily differences , new immigrants became easy targets for hatred and discrimination . If jobs were hard to , or if housing was overcrowded , it became easy to blame the immigrants . Like African Americans , immigrants in cities were blamed for the problems of the day .

504 19 The Growing Pains of Urbanization , Growing numbers of Americans resented the waves of new immigrants , resulting in a backlash . The Reverend Josiah Strong fueled the hatred and discrimination in his bestselling book , Our Country Its Possible Future and Its Present Crisis , published in 1885 . In a revised edition that reflected the 1890 census records , he clearly undesirable from southern and eastern European a key threat to the moral of the country , and urged all good Americans to face the challenge . Several thousand Americans answered his call by forming the American Protective Association , the chief political activist group to promote legislation curbing immigration into the United States . The group successfully lobbied Congress to adopt both an English language literacy test for immigrants , which eventually passed in 1917 , and the Chinese Exclusion Act ( discussed in a previous chapter ) The group political lobbying also laid the groundwork for the subsequent Emergency Quota Act of 1921 and the Immigration Act of 1924 , as well as the National Origins Act . CLICK AND EXPLORE The global timeline of immigration ( at the Library offers a summary of immigration policies and the groups affected by it , as well as a compelling overview of different ethnic groups immigration stories . Browse through to see how different ethnic groups made their way in the United States . Relief from the Chaos of Urban Life LEARNING OBJECTIVES By the end ofthis section , you will be able to Identify how each class of class , middle class , and upper to the challenges associated with urban life Explain the process of machine politics and how it brought relief to Americans Settlement houses and religious and civic organizations attempted to provide some support to city dwellers through free health care , education , and leisure opportunities . Still , for urban citizens , life in the city was chaotic and challenging . But how that chaos manifested and how relief was sought differed greatly , depending on where people were in the social working class , the upper class , or the newly emerging professional middle addition to the aforementioned issues of race and ethnicity . While many communities found life in the largest American cities disorganized and overwhelming , the ways they answered these challenges were as diverse as the people who lived there . Broad solutions emerged that were typically class The rise of machine politics and popular culture provided relief to the working class , higher education opportunities and suburbanization the professional middle class , and reminders of their elite status gave comfort to the upper class . And everyone , no matter where they fell in the class system , from the efforts to improve the physical landscapes of the urban environment . THE LIFE AND STRUGGLES OF THE URBAN WORKING CLASS For the residents of America cities , one practical way of coping with the challenges of urban life was to take advantage of the system of machine politics , while another was to seek relief in the variety of popular culture and entertainment found in and around cities . Although neither of these forms of relief was restricted to the working class , they were the ones who relied most heavily on them . Machine Politics The primary form of relief for urban Americans , and particularly immigrants , came in the form of machine politics . This phrase referred to the process by which every citizen of the city , no matter their ethnicity or race , was a ward resident with an alderman who spoke on their behalf at city hall . When everyday challenges arose , whether sanitation problems or the need for a sidewalk along a muddy road , citizens would approach their alderman to a solution . The aldermen knew that , rather than work through the long bureaucratic process associated with city hall , they could work within the machine of local politics to a Access for free at .

Relief from the Chaos of Urban Life 505 speedy , mutually solution . In machine politics , favors were exchanged for votes , votes were given in exchange for fast solutions , and the price of the solutions included a kickback to the boss . In the short term , everyone got what they needed , but the process was neither transparent nor democratic , and it was an way of conducting the city business . One example of a machine political system was the Democratic political machine Tammany Hall in New York , run by machine boss William Tweed with assistance from George Washington ( Figure ) There , citizens knew their immediate problems would be addressed in return for their promise of political support in future elections . In this way , machines provided timely solutions for citizens and votes for the politicians . For example , if in Little Italy there was a desperate need for sidewalks in order to improve to the stores on a particular street , the request would likely get bogged down in the bureaucratic red tape at city hall . Instead , store owners would approach the machine . A district captain would approach the boss and make him aware of the problem . The boss would contact city politicians and strongly urge them to appropriate the needed funds for the sidewalk in exchange for the promise that the boss would direct votes in their favor in the upcoming election . The boss then used the funds to pay one of his friends for the sidewalk construction , typically at an exorbitant cost , with a kickback to the boss , which was known as graft . The sidewalk was built more quickly than anyone hoped , in exchange for the citizens promises to vote for supported candidates in the next elections . Despite its corrupt nature , Tammany Hall essentially ran New York politics from the 18505 until the 19305 . Other large cities , including Boston , Philadelphia , Cleveland , Louis , and Kansas City , made use of political machines as well . mars 11 Turn . I um ! an no pun In do am in FIGURE This political cartoon depicts the control of Boss Tweed , of Tammany Hall , over the election process in New York . Why were people willing to accept the corruption involved in machine politics ?

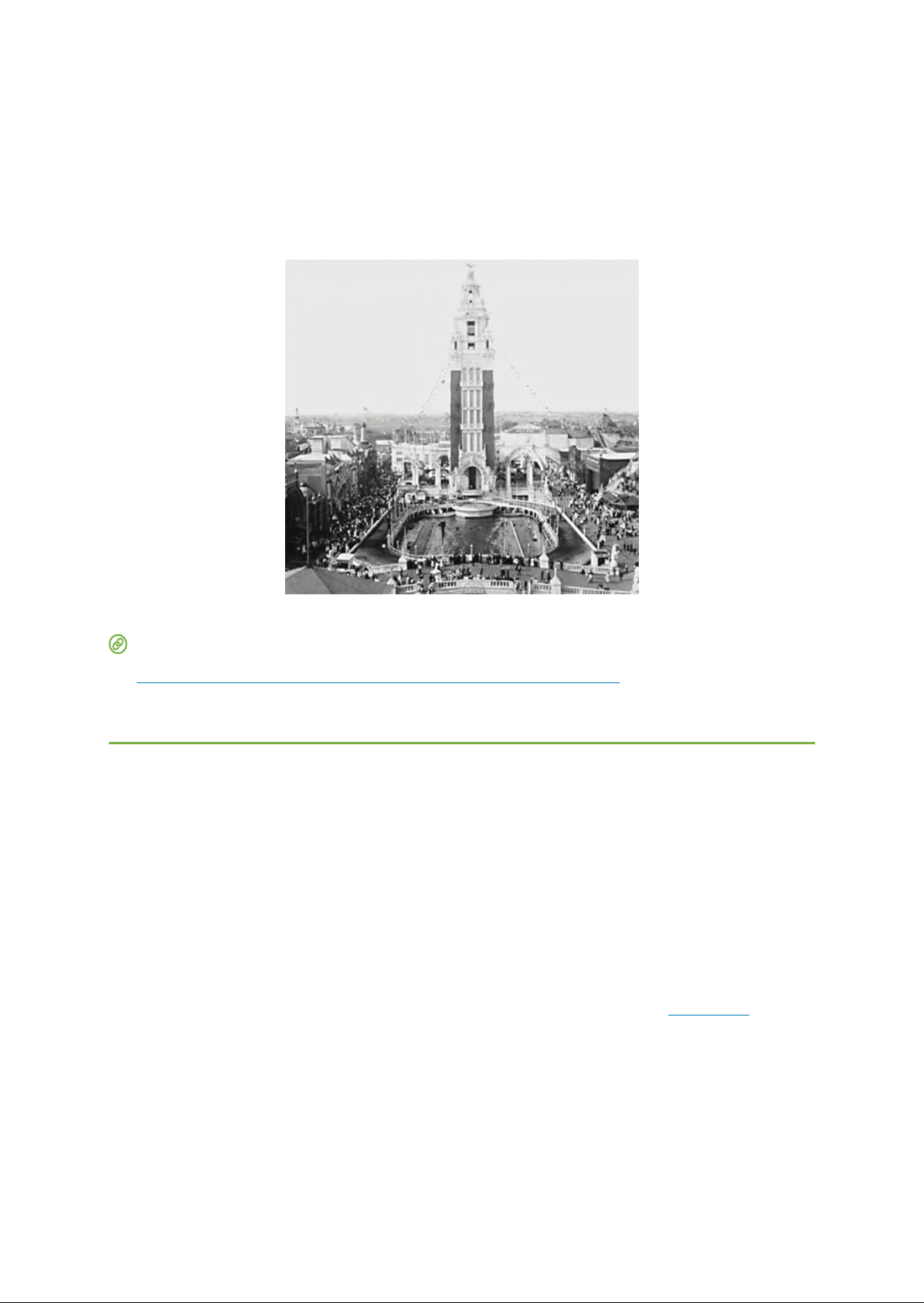

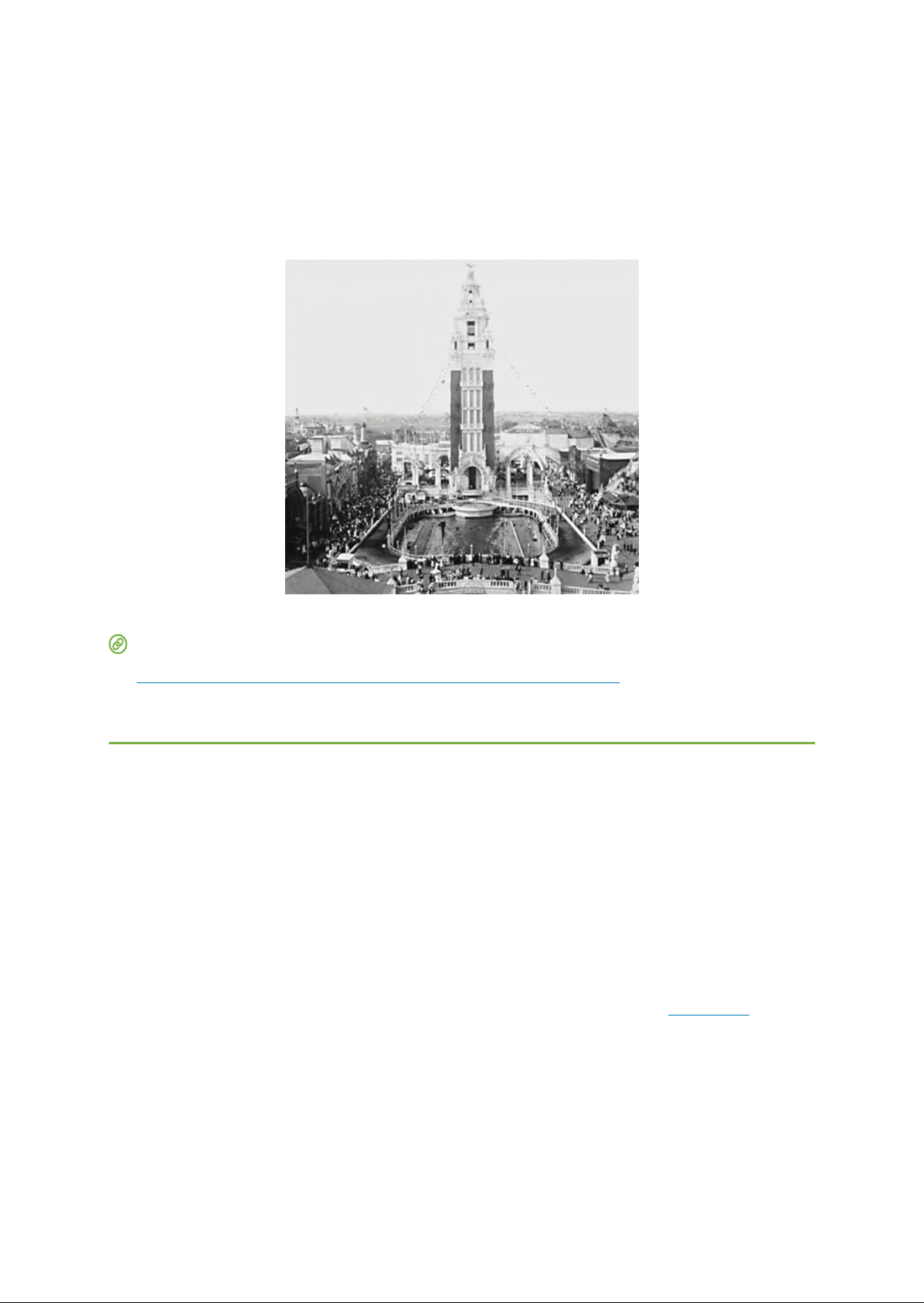

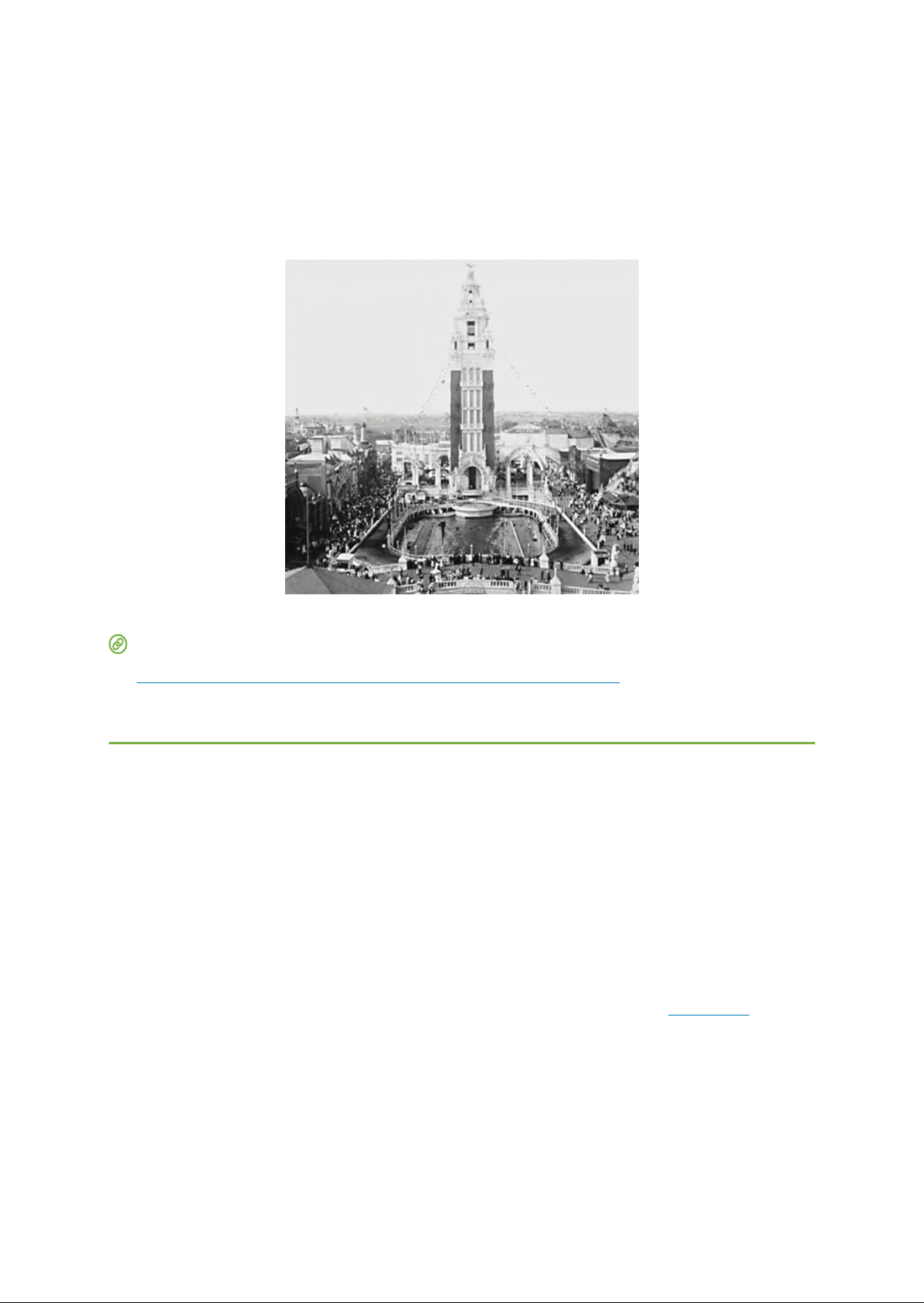

Popular Culture and Entertainment residents also found relief in the diverse and omnipresent offerings of popular culture and entertainment in and around cities . These offerings provided an immediate escape from the squalor and of everyday life . As improved means of internal transportation developed , residents could escape the city and experience one of the popular new forms of amusement park . For example , Coney Island on the Brooklyn shoreline consisted of several different amusement parks , the first of which opened in 1895 ( Figure 1911 ) At these parks , New Yorkers enjoyed wild rides , animal attractions , and large stage productions designed to help them forget the struggles of their lives . Freak side

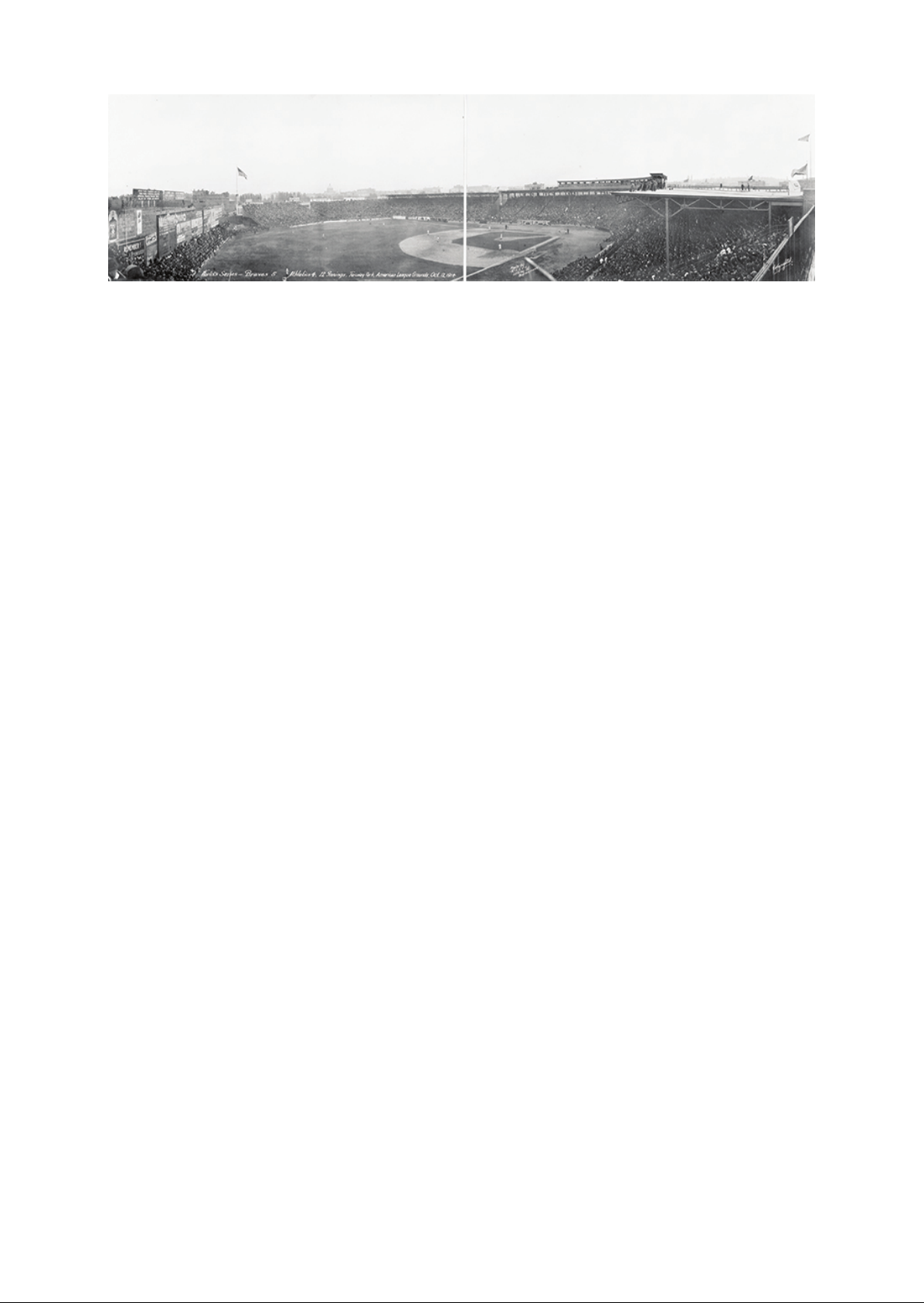

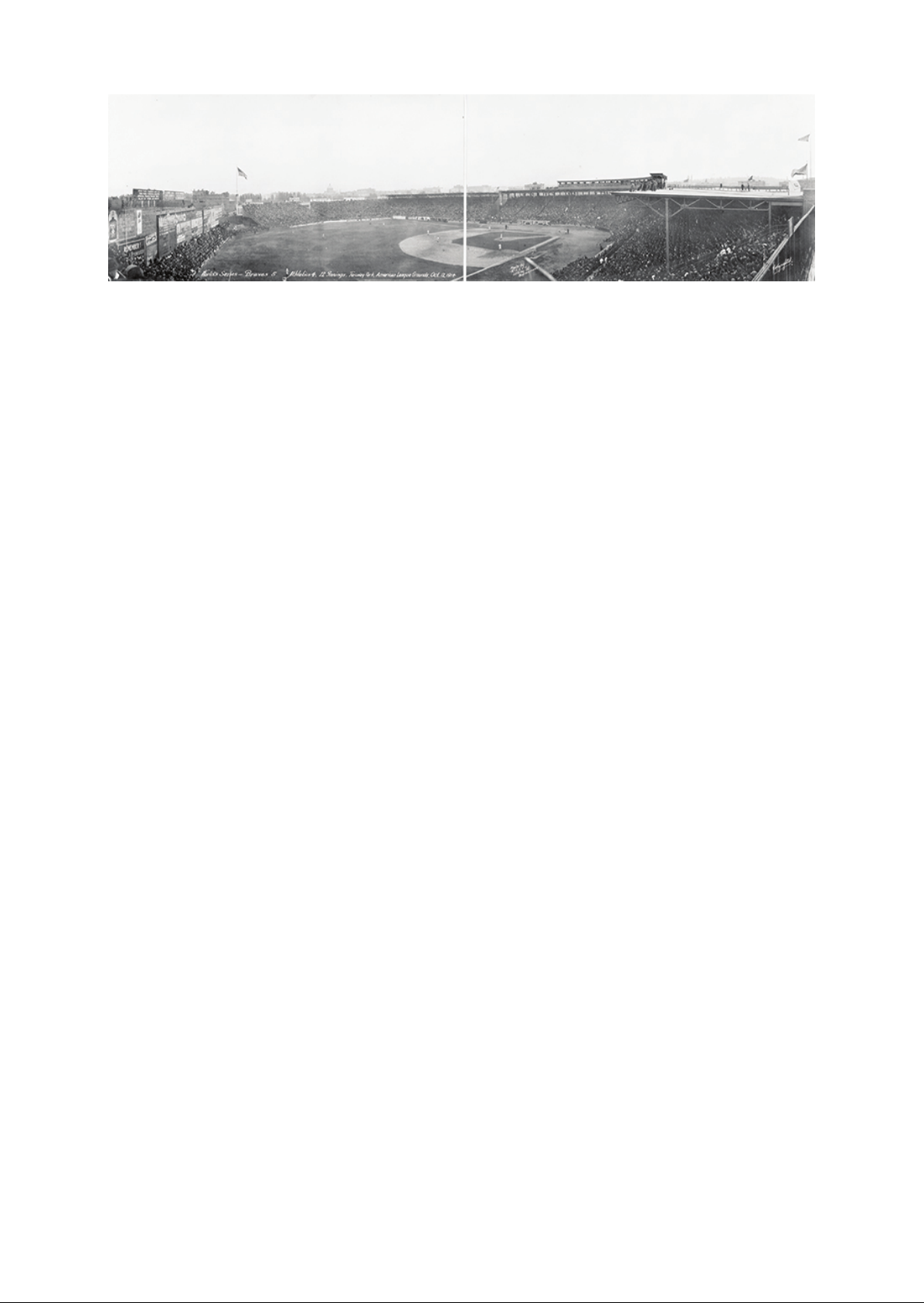

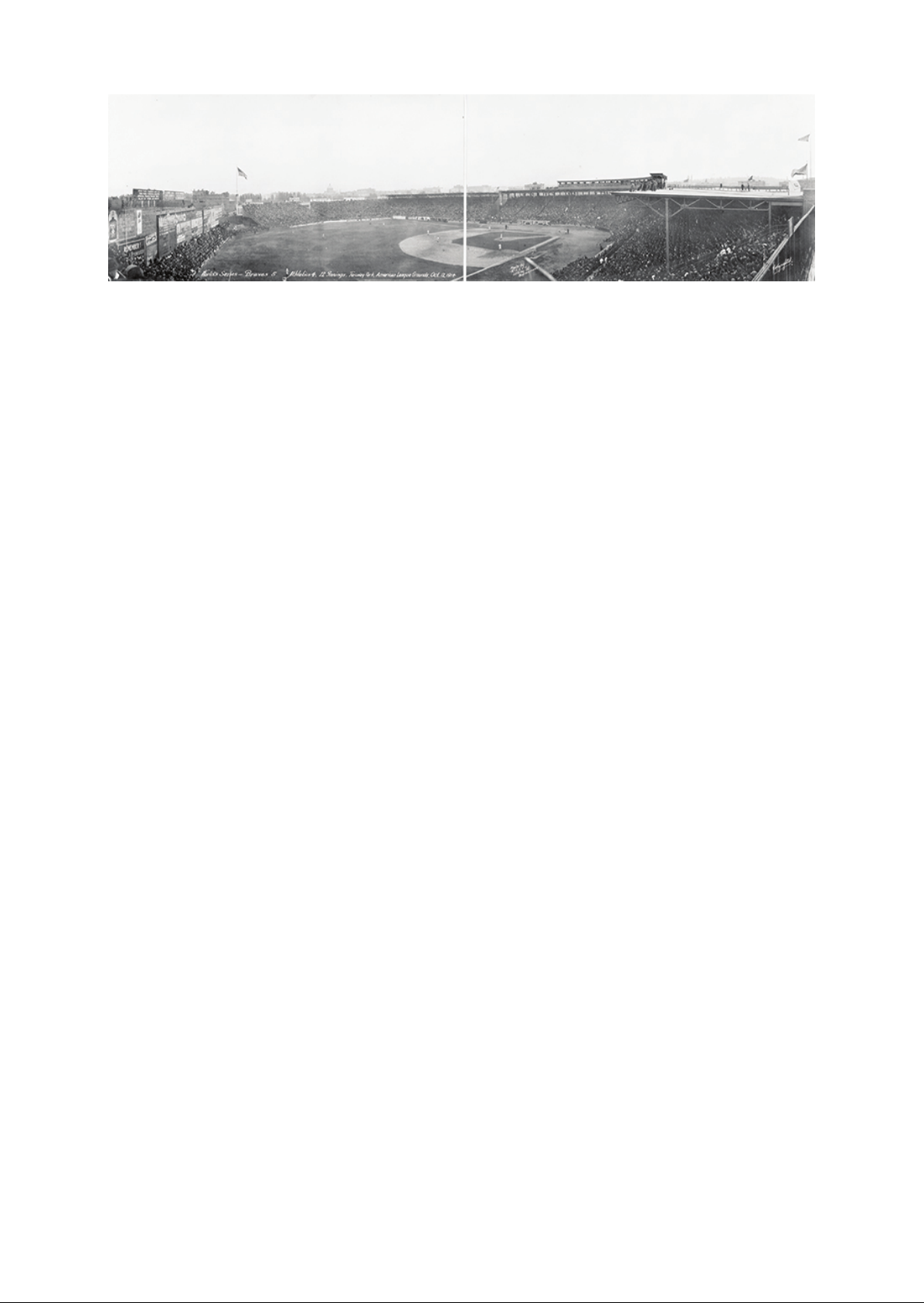

506 19 The Growing Pains of Urbanization , shows fed the public curiosity about physical deviance . For a mere ten cents , spectators could watch a diving horse , take a ride to the moon to watch moon maidens eat green cheese , or witness the electrocution of an elephant , a spectacle that fascinated the public both with technological marvels and exotic wildlife . The treatment of animals in many acts at Coney Island and other public amusement parks drew the attention of reformers such as the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals . Despite questions regarding the propriety of many of the acts , other cities quickly followed New York lead with similar , if smaller , versions of Coney Island attractions . um ( I FIGURE The Dreamland Amusement Park tower was just one of Coney Island amusements . CLICK AND EXPLORE The Island Proiect ( collection ) shows a photographic history of Coney Island . Look to see what elements of American culture , from the hot dog to the roller coaster , debuted there . Another common form of popular entertainment was stage variety shows that included everything from singing , dancing , and comedy acts to live animals and magic . The vaudeville circuit gave rise to several prominent performers , including magician Harry Houdini , who began his career in these variety shows before his fame propelled him to solo acts . In addition to live theater shows , it was primarily class citizens who enjoyed the advent of the nickelodeon , a forerunner to the movie theater . The nickelodeon opened in Pittsburgh in 1905 , where nearly one hundred visitors packed into a storefront theater see a traditional vaudeville show interspersed with clips . Several theaters initially used the as chasers to indicate the end of the show to the live audience so they would clear the auditorium . However , a vaudeville performers strike generated even greater interest in the , eventually resulting in he rise of modern movie theaters by 1910 . One other major form of entertainment for the working class was professional baseball Figure 1912 . Club eams transformed into professional baseball teams with the Cincinnati Red Stockings , now the Cincinnati Reds , in 1869 . Soon , professional teams sprang up in several major American cities . Baseball games provided an inexpensive form of entertainment , where for less than a dollar , a person could enjoy a , two dogs , and a beer . But more importantly , the teams became a way for newly relocated Americans and immigrants of diverse backgrounds to develop a civic identity , all cheering for one team . By 1876 , the National League had formed , and soon after , ballparks began to spring up in many cities . Fenway Park in Boston ( 1912 ) Forbes Field in Pittsburgh ( 1909 ) and the Polo Grounds in New York ( 1890 ) all touch points where Americans came together to support a common cause . Access for free at .

Relief from the Chaos of Urban Life 507 FIGURE Boston Fenway Park opened in 1912 and was a popular site for Bostonians to spend their leisure time . The Green Monster , the iconic , left wall , makes it one ofthe most recognizable stadiums in baseball today . Other popular sports , which attracted a predominantly male , and class audience who lived vicariously through the triumphs of the boxers during a time where opportunities for individual success were rapid shrinking , and college football , which paralleled a modern corporation in its team hierarchy , divisions of duties , and emphasis on time management . THE UPPER CLASS IN THE CITIES The American elite id not need to crowd into cities to work , like their counterparts . But as urban centers were vital business cores , where deals were made daily , those who in that world wished to remain close to the action . The rich chose to be in the midst of the chaos of the cities , but they were also able to provide measures of comfort , convenience , and luxury for . Wealthy citizens seldom attended what they considered the crass entertainment of the working class . Instead of amusement parks and baseball games , urban elites sought out more pastimes that underscored their knowledge of art and cu ture , preferring classical music concerts , art collections , and social gatherings with their peers . In New York , Andrew Carnegie built Carnegie Hall in 1891 , which quickly became the center of classical music performances in the country . Nearby , the Metropolitan Museum of Art opened its doors in 1872 and still remains one of the largest collections of art in the world . Other cities followed suit , and these cultural pursuits became a way for the upper class to remind themselves of their elevated place amid urban squalor . As new opportunities for the middle class threatened the austerity of citizens , including the newer forms of transportation that allowed Americans to travel with greater ease , wealthier Americans sought unique ways to further set themselves apart in society . These included more expensive excursions , such as vacations in Newport , Rhode Island , winter relocation to sunny Florida , and frequent trips aboard steamships to Europe . For those who were not of the highly respected old money , but only recently obtained their riches through business ventures , the relief they sought came in the form of one annual Social Register . First published in 1886 by Louis Keller in New York City , the register became a directory of the wealthy socialites who populated the city . Keller updated it annually , and people would watch with varying degrees of anxiety or complacency to see their names appear in print . Also called the Blue Book , the register was instrumental in the planning of society dinners , balls , and other social events . For those of newer wealth , there was relief found simply in the notion that they and others witnessed their wealth through the publication of their names in the register . A NEW MIDDLE CLASS While the working class were to tenement houses in the cities by their need to be close to their work and the lack of funds to anyplace better , and the wealthy class chose to remain in the cities to stay close to the action of big business transactions , the emerging middle class responded to urban challenges with their own solutions . This group included the managers , salesmen , engineers , doctors , accountants , and other

508 19 The Growing Pains of Urbanization , salaried professionals who still worked for a living , but were better educated and compensated han the poor . For this new middle class , relief from the trials of the cities came through education and suburbanization . In large part , the middle class responded to the challenges of the city by physically escaping it . As improved and outlying communities connected to urban centers , the middle class embraced a new type of suburbs . It became possible for those with adequate means to work in the city and escape each evening , by way of a train or trolley , to a house in the suburbs . As the number of people moving to he suburbs grew , there also grew a perception among the middle class that the farther one lived from the city and the more amenities one had , the more affluence one had achieved . Although a few suburbs existed in the United States prior to the ( such as Park , New Jersey ) he introduction of the electric railway generated greater interest and growth during the last decade of the century . The ability to travel from home to work on a relatively quick and cheap mode of transportation encouraged more Americans of modest means to consider living away from the chaos of the city . Eventually , Henry Ford popularization of the automobile , in terms of a lower price , permitted more families own cars and thus consider suburban life . Later in the twentieth century , both the advent of the interstate system , along with federal legislation designed to allow families to construct homes with , further sparked the suburban phenomenon . New Roles for Women Social norms of the day encouraged women to take great pride in creating a positive home environment for their working husbands and children , which reinforced the business and educational principles that they practiced on the job or in school . It was at this time that the magazines Ladies Home Journal and Good distribution , to tremendous popularity ( Figure 1913 ) GOOD AUGUST 998 ( FIGURE The family of the late nineteenth century largely embraced a separation of gendered spheres that had first emerged during the market revolution of the antebellum years . Whereas the husband earned money for the family outside the home , the wife oversaw domestic chores , raised the children , and tended to the family spiritual , social , and cultural needs . The magazine Good Housekeeping , launched in 1885 , capitalized on the woman focus on home . While the vast majority of women took on the expected role of housewife and homemaker , some women were paths to college . A small number of men colleges began to open their doors to women in the , and became an option . Some of the most elite universities created Access for free at .

Relief from the Chaos of Urban Life 509 women colleges , such as Radcliffe College with Harvard , and Pembroke College with Brown University . But more importantly , the women colleges opened at this time . Mount , Vassar , Smith , and Colleges , still some of the best known women schools , opened their doors between 1865 and 1880 , and , although enrollment was low ( initial class sizes ranged from students at Vassar to seventy at , at Smith , and up to at Mount ) the opportunity for a higher education , and even a career , began to emerge for young women . These schools offered a unique , environment in which professors and a community of young women came together . While most young women still married , their education offered them new opportunities to work outside the home , most frequently as teachers , professors , or in the aforementioned settlement house environments created by Jane Addams and others . Education and the Middle Class Since the children of the professional class did not have to leave school and work to support their families , they had opportunities for education and advancement that would solidify their position in the middle class . They also from the presence of mothers , unlike children , whose mothers typically worked the same long hours as their fathers . Public school enrollment exploded at this time , with the number of students attending public school tripling from seven million in 1870 to million in 1920 . Unlike the , larger schools slowly began the practice of employing different teachers for each grade , and some even began hiring instructors . High schools also grew at this time , from one hundred high schools nationally in 1860 to over six thousand by 1900 . The federal government supported the growth of higher education with the Acts of 1862 and 1890 . These laws set aside public land and federal funds to create colleges that were affordable to class families , offering courses and degrees useful in the professions , but also in trade , commerce , industry , and agriculture ( Figure 1914 . colleges stood in contrast to the expensive , private Ivy League universities such as Harvard and Yale , which still catered to the elite . Iowa became the state to accept the provisions of the original Act , creating what later became Iowa State University . Other states soon followed suit , and the availability of an affordable college education encouraged a boost in enrollment , from students nationwide in 1870 to over students by 1920 . I ' um um I In FIGURE This rendering of Kansas State University in 1878 shows an early college , created by the Act . These newly created schools allowed many more students to attend college than the elite Ivy League system , and focused more on preparing them for professional careers in business , medicine , and law , as well as business , agriculture , and other trades . College curricula also changed at this time . Students grew less likely to take traditional liberal arts classes in rhetoric , philosophy , and foreign language , and instead focused on preparing for the modern work world . Professional schools for the study of medicine , law , and business also developed . In short , education for the children of parents catered to interests and helped ensure that parents could establish their children comfortably in the middle class as well .

510 19 The Growing Pains of Urbanization , CITY BEAUTIFUL While the working poor lived in the worst of it and the wealthy elite sought to avoid it , all city dwellers at the time had to deal with the harsh realities of urban sprawl . Skyscrapers rose and the air , streets were crowded with pedestrians of all sorts , and , as developers worked to meet the demand for space , the few remaining green spaces in the city quickly disappeared . As the population became increasingly centered in urban areas while the century drew to a close , questions about the quality of city with regard to issues of aesthetics , crime , and consumed many reformers minds . Those and wealthier urbanites who enjoyed the costlier amenities presented by city theaters , restaurants , and free to escape to the suburbs , leaving behind the poorer working classes living in squalor and unsanitary conditions . Through the City Beautiful movement , leaders such as Frederick Law Olmsted and Daniel sought to champion and progressive reforms . They improved the quality of life for city dwellers , but also cultivated dominated urban spaces in which Americans of different ethnicities , racial origins , and classes worked and lived . Olmsted , one of the earliest and most designers of urban green space , and the original designer of Central Park in New York , worked with to introduce the idea of the City Beautiful movement at the Columbian Exposition in 1893 . There , they helped to design and construct the White City named for the plaster of Paris construction of several buildings that were subsequently painted a bright example of landscaping and architecture that shone as an example of perfect city planning . From green spaces to brightly painted white buildings , connected with modern transportation services and appropriate sanitation , the White City set the stage for American urban city planning for the next generation , beginning in 1901 with the modernization of Washington , This model encouraged city planners to consider three principal tenets First , create larger park areas inside cities second , build wider boulevards to decrease congestion and allow for lines of trees and other greenery between lanes and third , add more suburbs in order to mitigate congested living in the city itself ( Figure each city adapted these principles in various ways , the City Beautiful movement became a cornerstone of urban development well into the twentieth century . FIGURE This blueprint shows vision for Chicago , an example ofthe City Beautiful movement . His goal was to preserve much of the green space city lakefront , and to ensure that all city dwellers had access to green space . Access for free at .

Change Reflected in Thought and Writing 511 Change Reflected in Thought and Writing LEARNING OBJECTIVES By the end ofthis section , you will be able to Explain how American writers , both fiction and , helped Americans to better understand the changes they faced in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries Identify some of the influential women and African American writers of the era In the late nineteenth century , Americans were living in a world characterized by rapid change . Western expansion , dramatic new technologies , and the rise of big business drastically society in a matter of a few decades . For those living in the urban areas , the pace of change was even faster and harder to ignore . One result of this time of transformation was the emergence of a series of notable authors , who , whether writing or , offered a lens through which to better understand the shifts in American society . UNDERSTANDING SOCIAL PROGRESS One key idea of the nineteenth century that moved from the realm of science to the murkier ground of social and economic success was Charles Darwin theory of evolution . Darwin was a British naturalist who , in his 1859 work On the Origin of Species , made the case that species develop and evolve through natural selection , not through divine intervention . The idea quickly drew from the Anglican Church ( although a liberal branch of Anglicans embraced the notion of natural selection being part of God plan ) and later from many others , both in England and abroad , who felt that the theory directly contradicted the role of God in the earth creation . Although biologists , botanists , and most of the establishment widely accepted the theory of evolution at the time of Darwin publication , which they felt synthesized much of the previous work in the , the theory remained controversial in the public realm for decades . Political philosopher Herbert Spencer took Darwin theory of evolution further , coining the actual phrase survival of the , and later helping to popularize the phrase social Darwinism to posit that society evolved much like a natural organism , wherein some individuals will succeed due to racially and ethnically inherent traits , and their ability to adapt . This model allowed that a collection of traits and skills , which could include intelligence , inherited wealth , and so on , mixed with the ability to adapt , would let all Americans rise or fall of their own accord , so long as the road to success was accessible to all . William Graham Sumner , a sociologist at Yale , became the most vocal proponent of social Darwinism . Not surprisingly , this ideology , Darwin himsel would have rejected as a gross misreading of his discoveries , drew great praise rom those who made their wealth at this time . They saw their success as proof of biological , although critics of this theory were quick to point out that those who did not succeed often did not have the same opportunities or equal playing that the ideology of social Darwinism purported . Eventually , the concept into disrepute in tie 19305 and , as eugenicists began to utilize it in conjunction with their racial of genetic su . of realism that sought to understand the truth underlying the changes in the United States . These believed tha ideas and social constructs must be proven to work before they could be accepted . William ames was one of the key proponents of the closely related concept of pragmatism , which ield that Americans needed to experiment with different ideas and perspectives to the truth about American society , rat ter than assuming that there was truth in old , previously accepted models . Only by tying ic eas , thoughts , and statements to actual objects and occurrences could one begin to identify a coherent truth , according to James . is work strongly the subsequent and modernist movements in i and art , especially in understanding the role of the observer , artist , or writer in shaping the society hey attempted to observe . John Dewey built on the idea of pragmatism to create a theory of instrumentalism , advocated the use of education in the search for truth . Dewey believed that education , observation and change through the method , was the best tool by which to reform and improve her thinkers of the day took Charles Darwin theories in a more nuanced direction , focusing on different

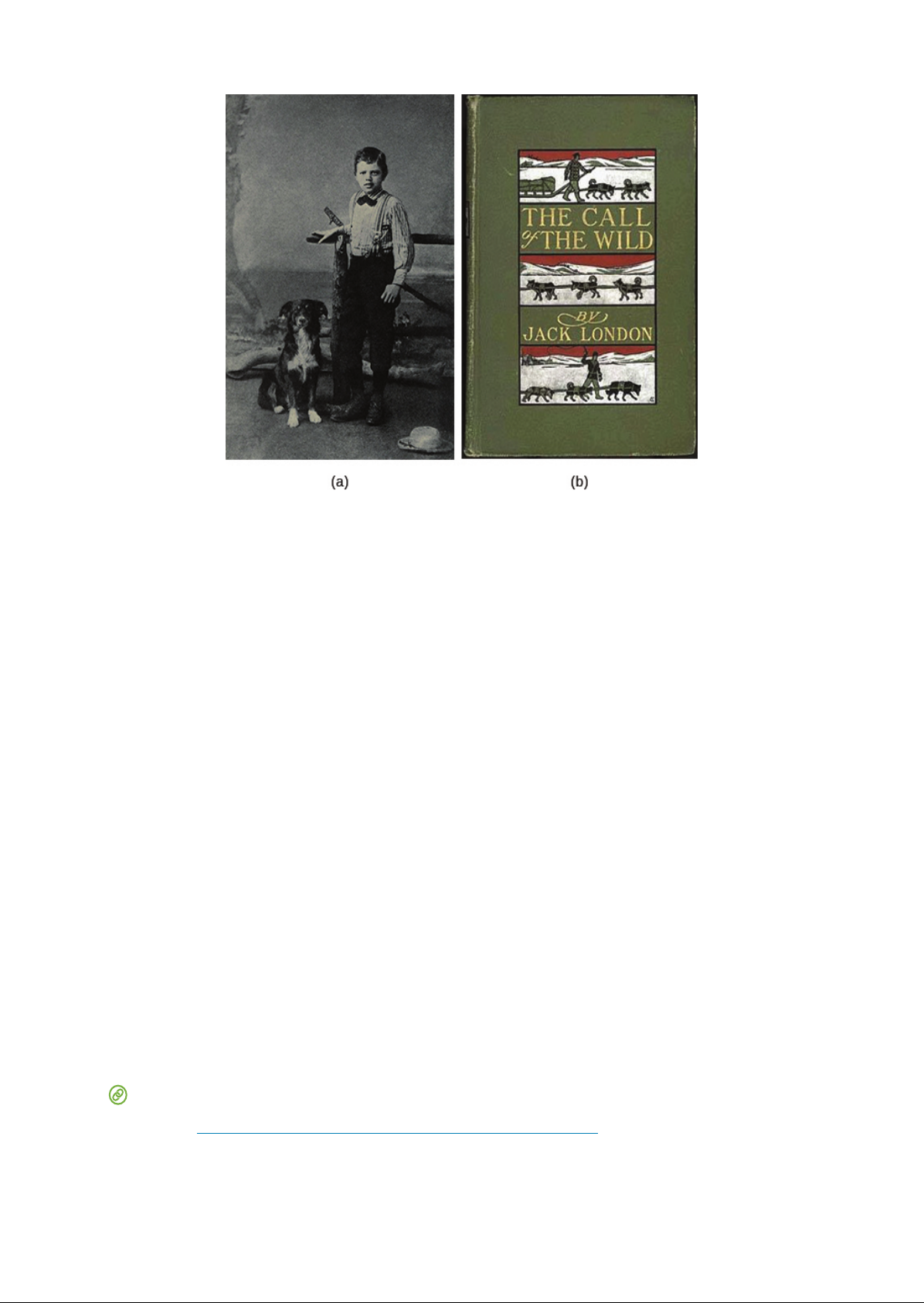

512 19 The Growing Pains of Urbanization , American society as it continued to grow ever more complex . To that end , Dewey strongly encouraged educational reforms designed to create an informed American citizenry that could then form the basis for other , progressive reforms in society . In addition to the new medium of photography , popularized by , novelists and other artists also embraced realism in their work . They sought to portray vignettes from real life in their stories , partly in response to the more sentimental works of their predecessors . Visual artists such as George Bellows , Edward Hopper , and Robert Henri , among others , formed the Ashcan School of Art , which was interested primarily in depicting the urban lifestyle that was quickly gripping the United States at the turn of the century . Their works typically focused on city life , including the slums and tenement houses , as well as forms of leisure and entertainment Figure . FIGURE Like most examples of works by Ashcan artists , The Cliff Dwellers , by George Wesley Bellows , depicts the crowd of urban life realistically . credit Los Angeles County Museum of Art ) Novelists and journalists also popularized realism in literary works . Authors such as Stephen Crane , who wrote stark stories about life in the slums or during the Civil War , and Rebecca Harding Davis , who in 1861 published Life in the Iron Mills , embodied this popular style . Mark Twain also sought realism in his books , whether it was the reality of the pioneer spirit , seen in of Huckleberry Finn , published in 1884 , or the issue of corruption in The Gilded Age , with Charles Dudley Warner in 1873 . The narratives and visual arts of these realists could nonetheless be highly stylized , crafted , and even fabricated , since their goal was the effective portrayal of social realities they thought required reform . Some authors , such as Jack London , who wrote The Call of the Wild , embraced a school of thought called naturalism , which concluded that the laws of nature and the natural world were the only truly relevant laws governing humanity Figure 1917 . Access for free at .

Change Reflected in Thought and Writing 513 ii I THE CALL I THE ) a ) FIGURE Jack London poses with his dog Rollo in 1885 ( a ) The cover of . London The Call ofthe Wild ( shows the dogs in the brutal environment ofthe Klondike . The book tells the story of Buck , a dog living happily in California until he is sold to be a sled dog in Canada . There , he must survive harsh conditions and brutal behavior , but his innate animal nature takes over and he prevails . The story the struggle between humanity nature versus the nurturing forces of society . Kate Chopin , widely regarded as the foremost woman short story writer and novelist of her day , sought to portray a realistic view of women lives in late America , thus paving the way for more explicit feminist literature in generations to come . Although Chopin never described herself as a feminist per se , her works on her experiences as a southern woman introduced a form of creative that captured the struggles of women in the United States through their own individual experiences . She also was among the authors to openly address the race issue of miscegenation , a term referring to interracial relations , which usually has negative associations . In her work Desiree Baby , Chopin explores the Creole community of her native Louisiana in depths that exposed the reality of racism in a manner seldom seen in literature of the time . African American poet , playwright , and novelist of the realist period , Paul Laurence Dunbar dealt with issues of race at a time when most Americans preferred to focus on other issues . Through his combination of writing in both standard English and Black dialect , Dunbar delighted readers with his rich portrayals of the successes and struggles associated with African American life . Although he initially struggled to the patronage and support required to develop a literary career , subsequent professional relationship with literary critic and Atlantic Monthly editor William Dean helped to cement his literary credentials as the foremost African American writer of his generation . As with Chopin and Harding Davis , Dunbar writing highlighted parts of the American experience that were not well understood by the dominant demographic of the country . In their work , these authors provided readers with insights into a world that was not necessarily familiar to them and also gave hidden it iron mill workers , southern women , or African American sense of voice . CLICK AND EXPLORE Mark Twain lampoon of author Horatio Alger ( demonstrates commitment to realism by mocking the myth set out by Alger , whose stories followed a common theme in which a poor but honest boy goes from rags to riches through a combination of luck and pluck . See how

514 19 The Growing Pains of Urbanization , Twain twists Alger hugely popular storyline in this piece of satire . DEFINING AMERICAN Kate Chopin An Awakening in an Unpopular Time Author Kate Chopin grew up in the American South and later moved to Louis , where she began writing stories to make a living after the death of her husband . She published her works throughout the late , with stories appearing in literary magazines and local papers . It was her second novel , The Awakening , which gained her notoriety and criticism in her lifetime , and ongoing literary fame after her death Figure . FIGURE Critics railed against Kate Chopin , the author of the 1899 novel The Awakening , criticizing its stark portrayal of a woman struggling with societal and her own desires . In the twentieth century , scholars rediscovered Chopin work and The Awakening is now considered part of the canon of American literature . The Awakening , set in the New Orleans society that Chopin knew well , tells the story of a woman struggling with the constraints of marriage who ultimately seeks her own over the needs of her family . The book deals far more openly than most novels of the day with questions of women sexual desires . It also flouted conventions by looking at the protagonist struggles with the traditional role expected of women . While a few contemporary reviewers saw merit in the book , most criticized it as immoral and unseemly . It was censored , called pure poison , and critics railed against Chopin herself . While Chopin wrote squarely in the tradition of realism that was popular at this time , her work covered ground that was considered too real for comfort . negative reception of the novel , Chopin retreated from public life and discontinued writing . She died years after its publication . After her death , Chopin work was largely ignored , until scholars rediscovered it in the late twentieth century , and her books and stories came back into print . The particular has been recognized as vital to the earliest edges of the modern feminist movement . Access for free at .

Change Reflected in Thought and Writing 515 CLICK AND EXPLORE Excerpts from interviews ( with David Chopin , Kate Chopin grandson , and a scholar who studies her work provide interesting perspectives on the author and her views . CRITICS OF MODERN AMERICA While many Americans at this time , both everyday working people and theorists , felt the changes of the era would lead to improvements and opportunities , there were critics of the emerging social shifts as well . Alt tough less popular than Twain and London , authors such as Edward Bellamy , Henry George , and were also in spreading critiques of the industrial age . While their critiques were quite dis met from each other , all three believed that the industrial age was a step in the wrong direction for the country . In me 1888 novel Looking Backward , Edward Bellamy portrays a utopian America in the year 2000 , with the country living in peace and harmony after abandoning the capitalist model and moving to a socialist state . In the book , Bellamy predicts the future advent of credit cards , cable entertainment , and su cooperatives that resemble a modern day . Looking Backward proved to be a popular bes seller ( only to Uncle Tom Cabin and Ben Hur among late publications ) and appealed to those who felt the industrial age ofbig business was sending the country in the wrong direction . Eugene Debs , who led the national Pullman Railroad Strike in 1894 , later commented on how Bellamy work influenced to adopt socialism as the answer to the exploitative industrial capitalist model . In addition , Bel amy work spurred the publication of no fewer than additional books or articles by other writers , either supporting Bellamy outlook or directly criticizing it . In 1897 , Bellamy felt compelled to publish a sequel , entitled Equality , in which he further explained ideas he had previously introduced concerning reform and women equality , as well as a world of vegetarians who speak a universal language . Another au hor whose work illustrated the criticisms of the day was writer Henry George , an economist best known for his 1879 work Progress and Poverty , which criticized the inequality found in an industrial economy . He suggested that , while people should own that which they create , all land and natural resources belong to all equally , and should be taxed through a single land tax in order to private land ownership . His thoughts many economic progressive reformers , as well as led ly to the creation of the board game , Monopoly . Another cri ique of late American capitalism was , who lamented in The Theory of the Leisure Class ( 1899 ) that capitalism created a middle class more preoccupied with its own comfort anc consumption than with maximizing production . In coining the phrase conspicuous consumption , the means by which one class of exploited the working class that produced the goods for their consumption . Such practices , including the creation of business trusts , served only to create a greater divide between the haves and in American society , and resulted in economic that required correction or reform .

516 19 Key Terms Key Terms City Beautiful a movement begun by Daniel and Fredrick Law Olmsted , who believed that cities should be built with three core tenets in mind the inclusion within city limits , the creation boulevards , and the expansion of more suburbs graft the kickback provided to city bosses in exchange for political favors Great Migration the name for the large wave of African Americans who left the South after the Civil War , mostly moving to cities in the Northeast and Upper Midwest instrumentalism a theory promoted by John Dewey , who believed that education was key to the search for the truth about ideals and institutions machine politics the process by which citizens of a city used their local ward alderman to work the machine of local politics to meet local needs within a neighborhood naturalism a theory of realism that states that the laws of nature and the natural world were the only relevant laws governing humanity pragmatism a doctrine supported by philosopher William James , which held that Americans needed to experiment and the truth behind underlying institutions , religions , and ideas in American life , rather than accepting them on faith realism a collection of theories and ideas that sought to understand the underlying changes in the United States during the late nineteenth century settlement house movement an early progressive reform movement , largely spearheaded by women , which sought to offer services such as childcare and free healthcare to help the working poor social gospel the belief that the church should be as concerned about the conditions of people in the secular world as it was with their afterlife Social Register a de facto directory of the wealthy socialites in each city , published by Louis Keller in 1886 Tammany Hall a political machine in New York , run by machine boss William Tweed with assistance from George Washington Summary Urbanization and Its Challenges Urbanization spread rapidly in the century due to a of factors . New technologies , such as electricity and steam engines , transformed factory work , allowing factories to move closer to urban centers and away from the rivers that had previously been vital sources of both water power and transportation . The growth of well as innovations such as electric lighting , which allowed them to run at all hours of the day and a massive need for workers , who poured in from both rural areas of the United States and from eastern and southern Europe . As cities grew , they were unable to cope with this rapid of workers , and the living conditions for the working class were terrible . Tight living quarters , with inadequate plumbing and sanitation , led to widespread illness . Churches , civic organizations , and the secular settlement house movement all sought to provide some relief to the urban working class , but conditions remained brutal for many new city dwellers . The African American Great Migration and New European Immigration For both African Americans migrating from the postwar South and immigrants arriving from southeastern Europe , a combination of push and pull factors their migration to America urban centers . African Americans moved away from the racial violence and limited opportunities that existed in the rural South , seeking wages and steady work , as well as the opportunity to vote safely as free men however , they quickly learned that racial discrimination and violence were not limited to the South . For European immigrants , famine and persecution led them to seek a new life in the United States , where , the stories said , the streets were paved in gold . Of course , in northeastern and midwestern cities , both groups found a more Access for free at .

19 Review Questions 517 challenging welcome than they had anticipated . City residents blamed recent arrivals for the ills of the cities , from overcrowding to a rise in crime . Activist groups pushed for legislation , seeking to limit the waves of immigrants that sought a better future in the United States . the Chaos of Urban Life The burgeoning cities brought together both rich and poor , working class and upper class however , the realities of urban dwellers lives varied dramatically based on where they fell in the social chain . Entertainment and activities were heavily dependent on ones status and wealth . For the working poor , amusement parks and baseball games offered inexpensive entertainment and a brief break from the squalor of the tenements . For the emerging middle class of salaried professionals , an escape to the suburbs kept them removed from the city chaos outside of working hours . And for the wealthy , immersion in arts and culture , as well as inclusion in the Social Register , allowed them to socialize exclusively with those they felt were of the same social status . The City Beautiful movement all city dwellers , with its emphasis on public green spaces , and more beautiful and practical city boulevards . In all , these different opportunities for leisure and pleasure made city life manageable for the citizens who lived there . Change Reflected in Thought and Writing Americans were overwhelmed by the rapid pace and scale of change at the close of the nineteenth century . Authors and thinkers tried to assess the meaning of the country seismic shifts in culture and society through their work . Fiction writers often used realism in an attempt to paint an accurate portrait of how people were living at the time . Proponents of economic developments and cultural changes cited social Darwinism as an acceptable model to explain why some people succeeded and others failed , whereas other philosophers looked more closely at Darwin work and sought to apply a model of proof and pragmatism to all ideas and institutions . Other sociologists and philosophers criticized the changes of the era , citing the inequities found in the new industrial economy and its negative effects on workers . Review Questions . Which of the following four elements was not essential for creating massive urban growth in late America ?

electric lighting communication improvements skyscrapers settlement houses . Which of the following did the settlement house movement offer as a means of relief for women ?

childcare job opportunities political advocacy relocation services . What technological and economic factors combined to lead to the explosive growth of American cities at this time ?

Why did African Americans consider moving from the rural South to the urban North following the Civil War ?

to be able to buy land to avoid slavery to work to further their education 518 19 Critical Thinking Questions . Which the following is true of late southern and eastern European immigrants , as opposed to their western and northern European predecessors ?

Sou hern and eastern European immigrants tended to be wealthier Sou hern and eastern European immigrants were , on the whole , more skilled and able to better paying employment . Many southern and eastern European immigrants acquired land in the West , while western and nor hern European immigrants tended to remain in urban centers . Ellis Island was the first destination for most southern and eastern Europeans . What made recent European immigrants the ready targets of more established city dwellers ?

What was the result this discrimination ?

Which of the following was a popular pastime for urban dwellers ?

foo ball games opera museums amusement parks . Which of the following was a disadvantage of machine politics ?

A . Immigrants did not have a voice . Taxpayers ultimately paid higher city taxes due to graft . Only wealthy parts of the city received timely responses . Citizens who voiced complaints were at risk for their safety . In what way did education play a crucial role in the emergence of the middle class ?

10 . Which of the following statements accurately represents argument in The Theory of the Leisure Class ?

A . All citizens of an industrial society would rise or fall based on their own innate merits . The tenets of naturalism were the only laws through which society should be governed . The middle class was overly focused on its own comfort and consumption . Land and natural resources should belong equally to all citizens . 11 . Which of the following was notan element of realism ?

social Darwinism instrumentalism naturalism pragmatism 12 . In what ways did writers , photographers , and visual artists begin to embrace more realistic subjects in their work ?

How were these responses to the advent of the industrial age and the rise of cities ?

Critical Thinking Questions 13 . What triumphs did the late nineteenth century witness in the realms of industrial growth , urbanization , and technological innovation ?

What challenges did these developments pose for urban dwellers , workers , and recent immigrants ?

How did city and everyday citizens respond to these challenges ?