The Challenges of the Twenty-First Century

Explore the The Challenges of the Twenty-First Century study material pdf and utilize it for learning all the covered concepts as it always helps in improving the conceptual knowledge.

The Challenges of the Twenty-First Century PDF Download

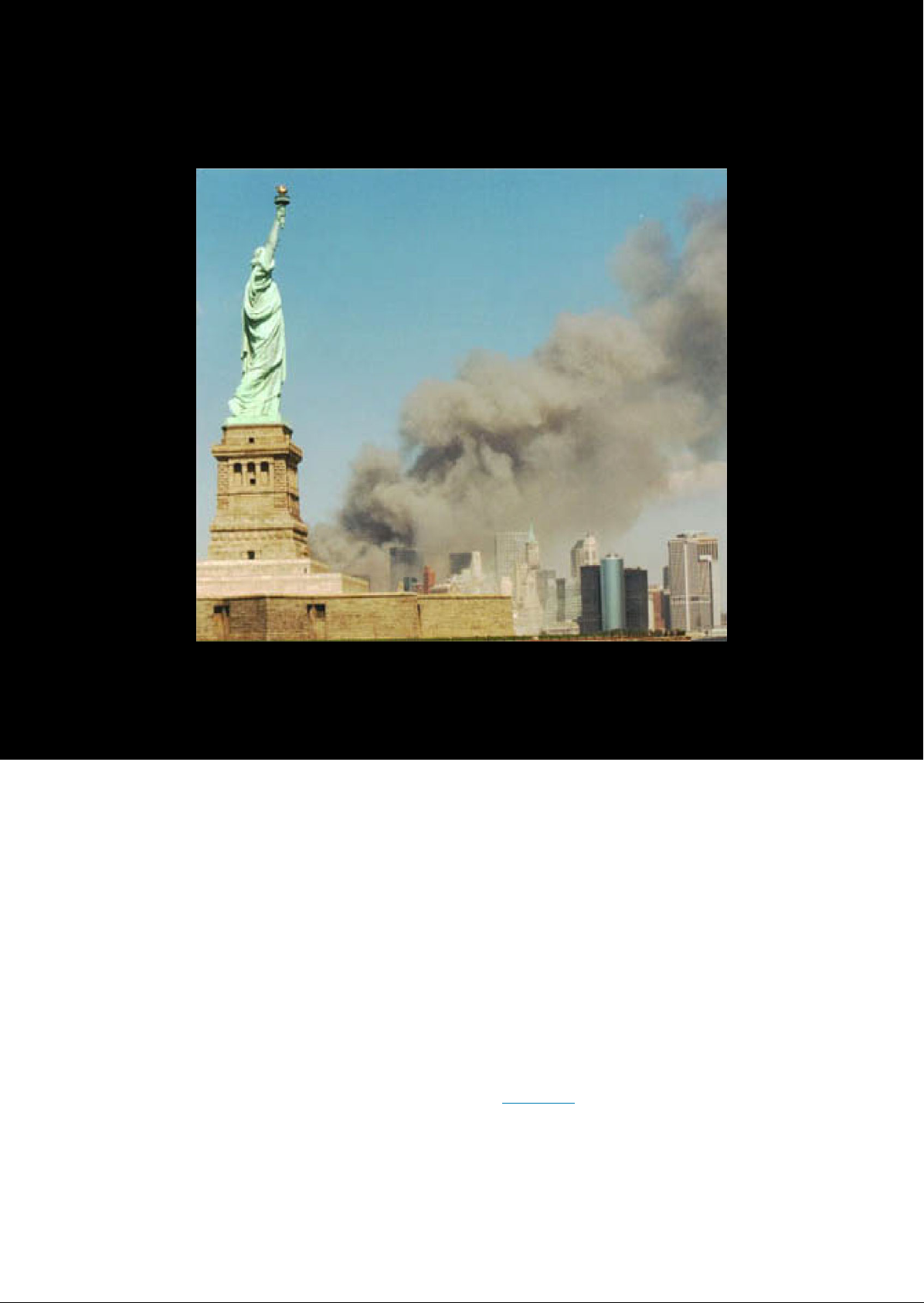

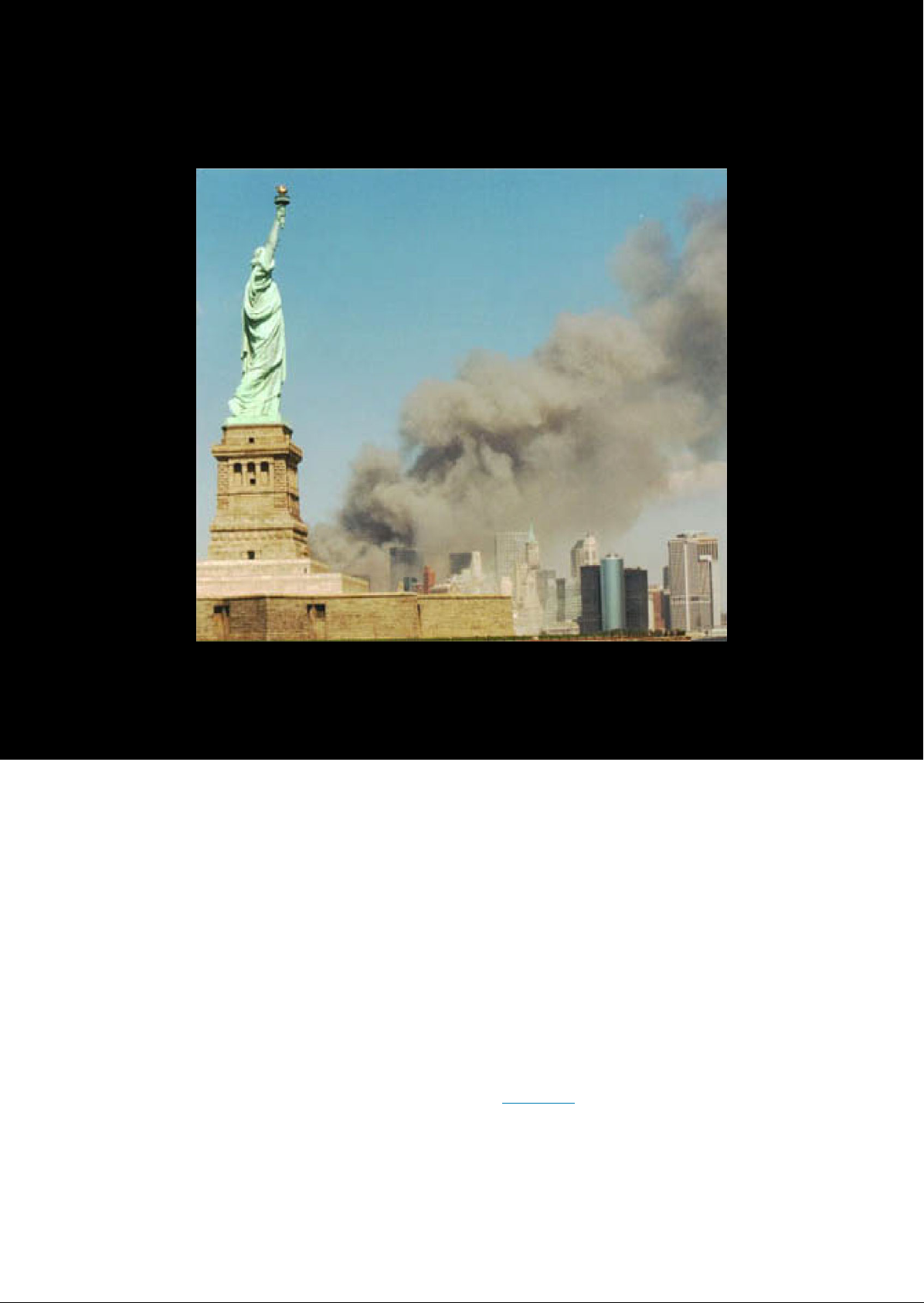

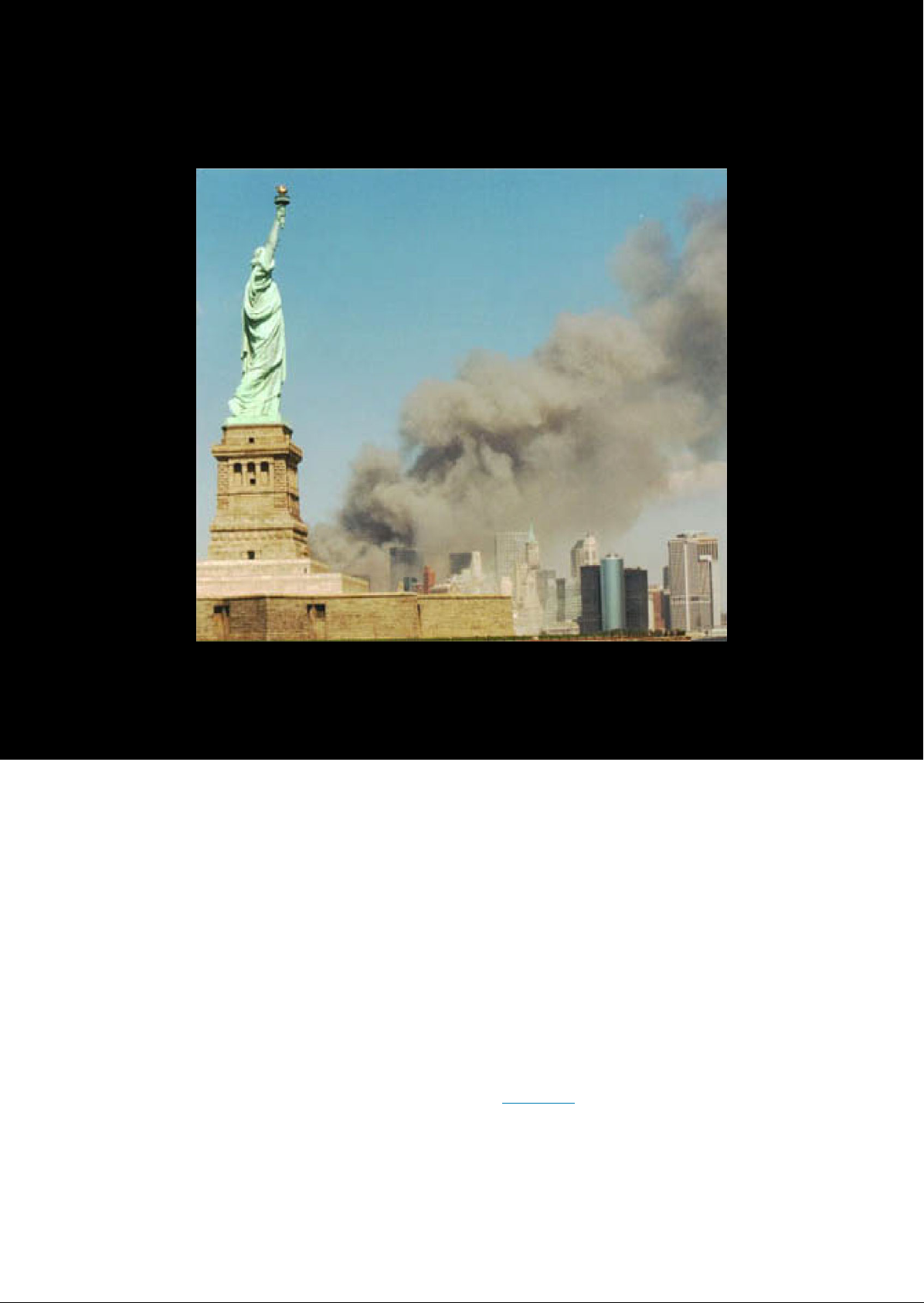

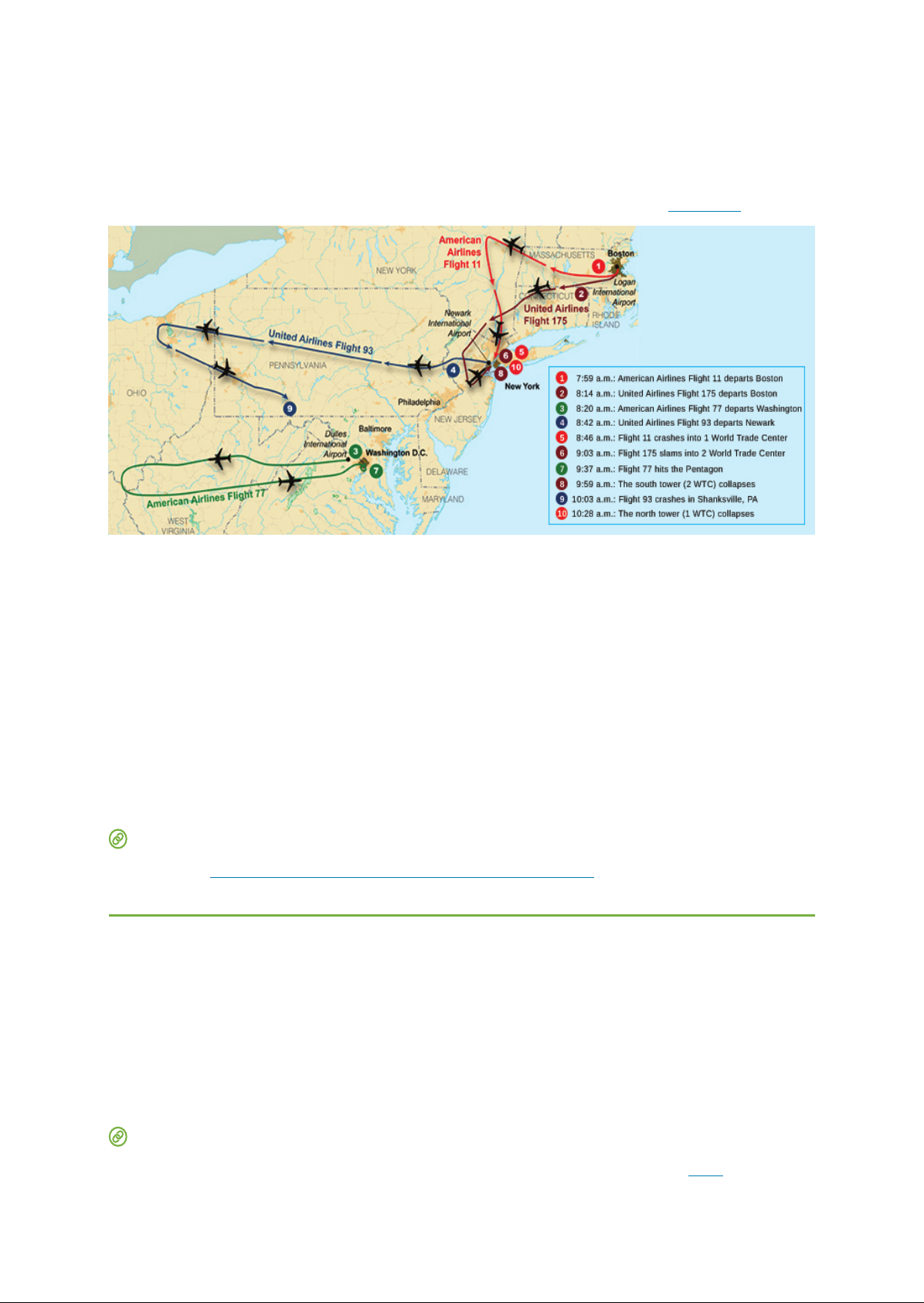

The Challenges of the Cen FIGURE In 2001 , almost three thousand people died as a result of the September 11 attacks , when members of the terrorist group hijacked four planes as part of a coordinated attack on sites in New York City and Washington , CHAPTER OUTLINE The War on Terror The Domestic Mission New Century , Old Disputes Hope and Change INTRODUCTION On the morning of September 11 , 2001 , hopes that the new century would leave behind the of the previous one were dashed when two hijacked airliners crashed into the twin towers of New York World Trade Center . When the plane struck the north tower , many assumed that the crash was a accident . But then a second plane hit the south tower less than thirty minutes later . People on the street watched in horror , as some of those trapped in the burning buildings jumped to their deaths and the enormous towers collapsed into dust . In the photo above , the Statue of Liberty appears to look on helplessly , as thick plumes of smoke obscure the Lower Manhattan skyline . The events set in motion by the September 11 attacks would raise fundamental questions about the United States role in the world , the extent to which privacy should be protected at the cost of security , the of exactly who is an American , and the cost of liberty .

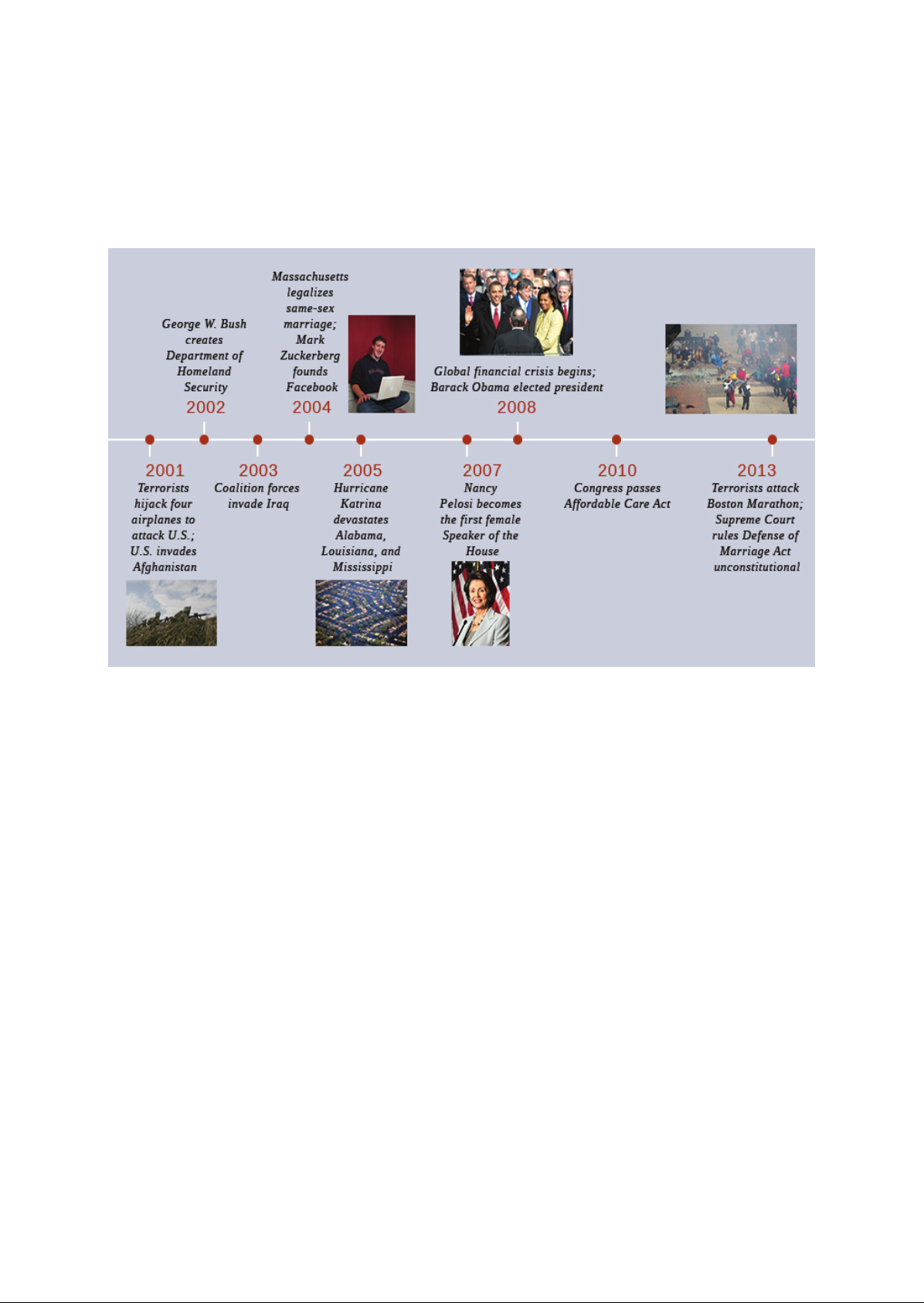

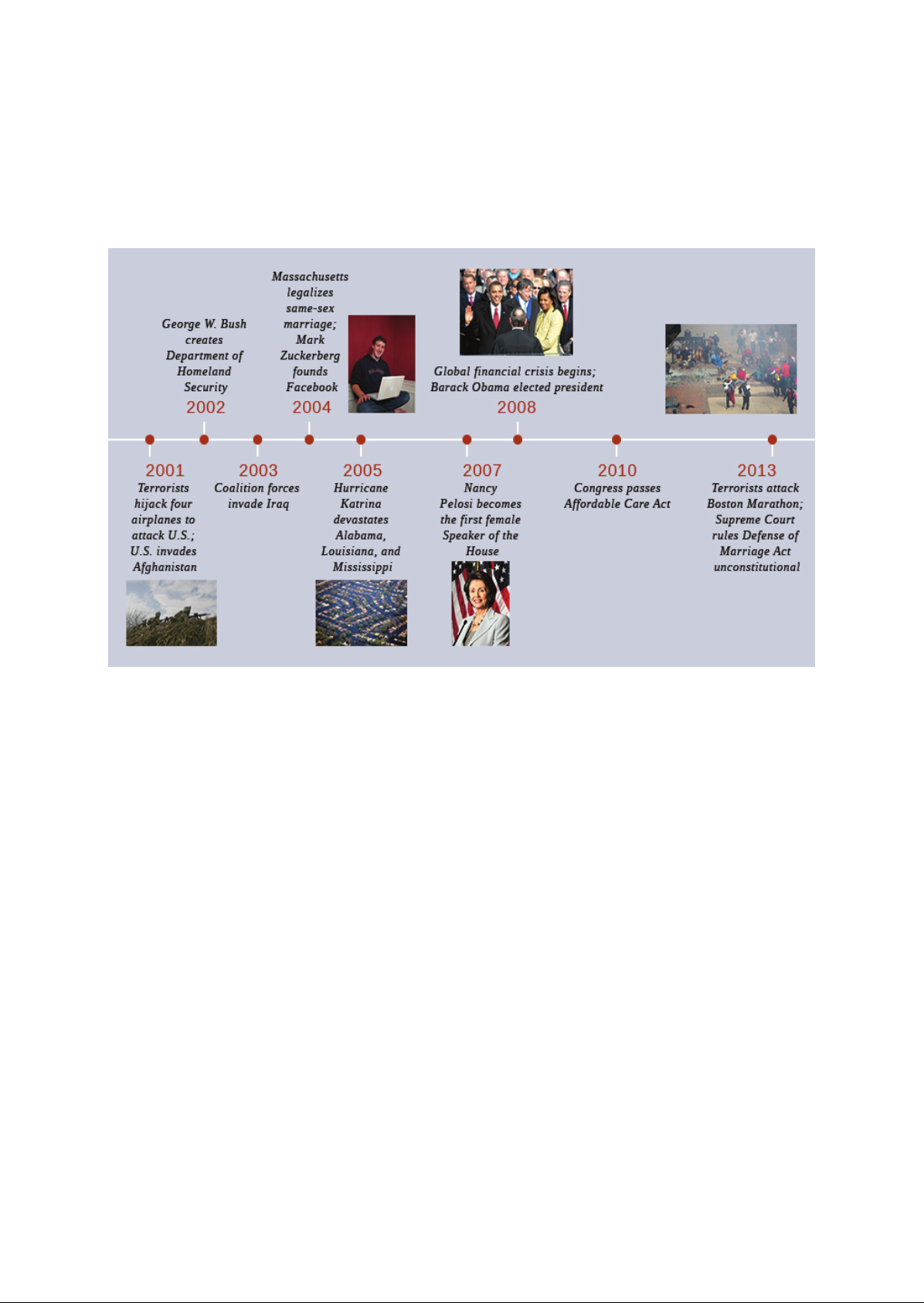

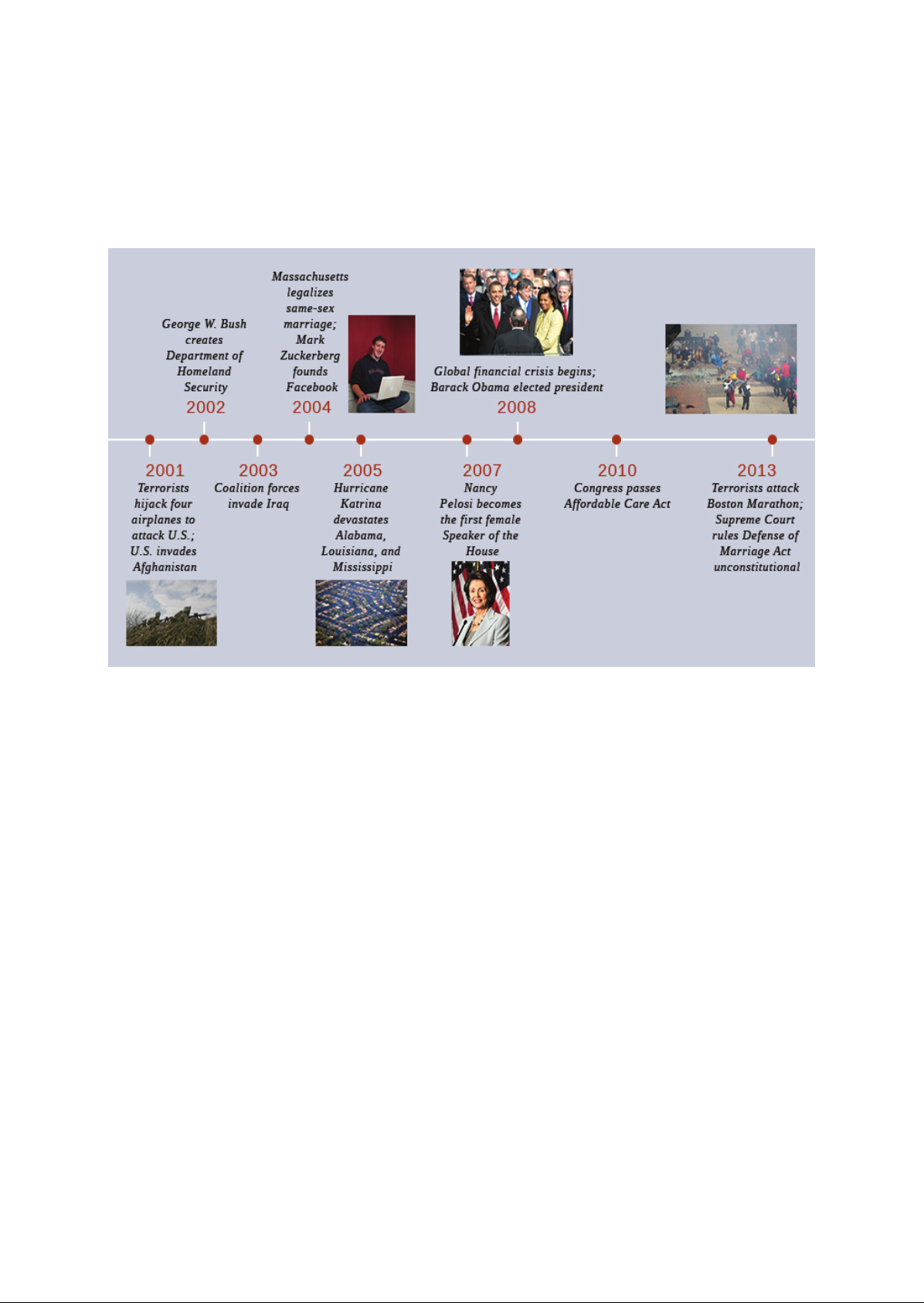

878 32 The Challenges of the Century The War on Terror LEARNING OBJECTIVES By the end ofthis section , you will be able to Discuss how the United States responded to the terrorist attacks of September Explain why the United States went to war against Afghanistan and Iraq Describe the treatment of suspected terrorists by law enforcement agencies and the military Massachusetts George Bush marriage creates Mark Department of Zuckerberg Homeland founds Global crisis begins Security Facebook Barack Obama elected president 2002 2004 2008 2001 2003 2005 2007 2010 2013 Terrorists Coalition forces Hurricane Nancy Congress posses Terrorists attack hijack four invade Iraq Katrina Pelosi becomes Care Act Boston Marathon airplanes to devastate the first female Supreme Court attack Alabama , Speaker of the rules Defense of invades Louisiana , and House Act Afghanistan Mississippi unconstitutional FIGURE ( credit 2004 of work by Elaine and Priscilla Chan credit 2013 of work by Tang credit 2001 of work by ) As a result of the narrow decision of the Supreme Court in Bush Gore , Republican George Bush was the declared the winner of the 2000 presidential election with a majority in the Electoral College of 271 votes to 266 , although he received approximately fewer popular votes nationally than his Democratic opponent , Bill Clinton vice president , Al Gore . Bush had campaigned with a promise of compassionate conservatism at home and nonintervention abroad . These platform planks were designed to appeal to those who felt that the Clinton administration initiatives in the Balkans and Africa had unnecessarily entangled the United States in the of foreign nations . Bush 2001 education reform act , clubbed No Child Left Behind , had strong bipartisan support and his domestic interests . But before the president could sign the bill into law , the world changed when four American airliners were hijacked and used in the single most deadly act of terrorism in the United States . Bush domestic agenda quickly took a backseat , as the president swiftly changed course from nonintervention in foreign affairs to a war on terror . Shortly after takeoff on the morning of September 11 , 2001 , teams of hijackers from the Islamist terrorist group seized control of four American airliners . Two of the airplanes were into the twin towers of the World Trade Center in Lower Manhattan . Morning news programs that were the moments after the impact , then assumed to be an accident , captured and aired live footage of the second plane , as it barreled into the other tower in a of and smoke . Less than two hours later , the heat from the crash and the explosion ofjet fuel caused the upper of both buildings to collapse onto the lower , reducing both towers to smoldering rubble . The passengers and crew on both planes , as well as people in the two buildings , all died , including 343 New York City who rushed in to save victims shortly before the Access for free at .

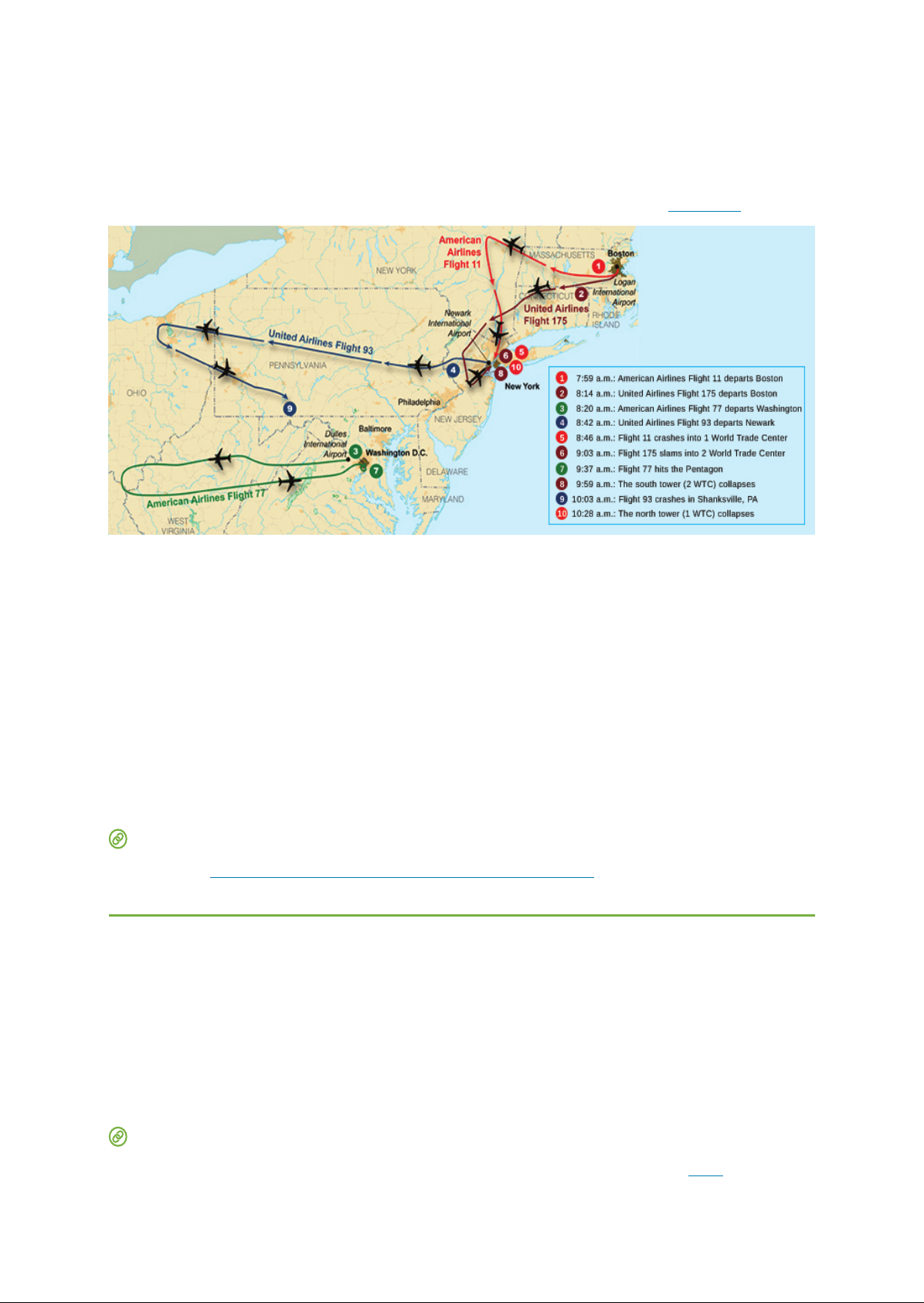

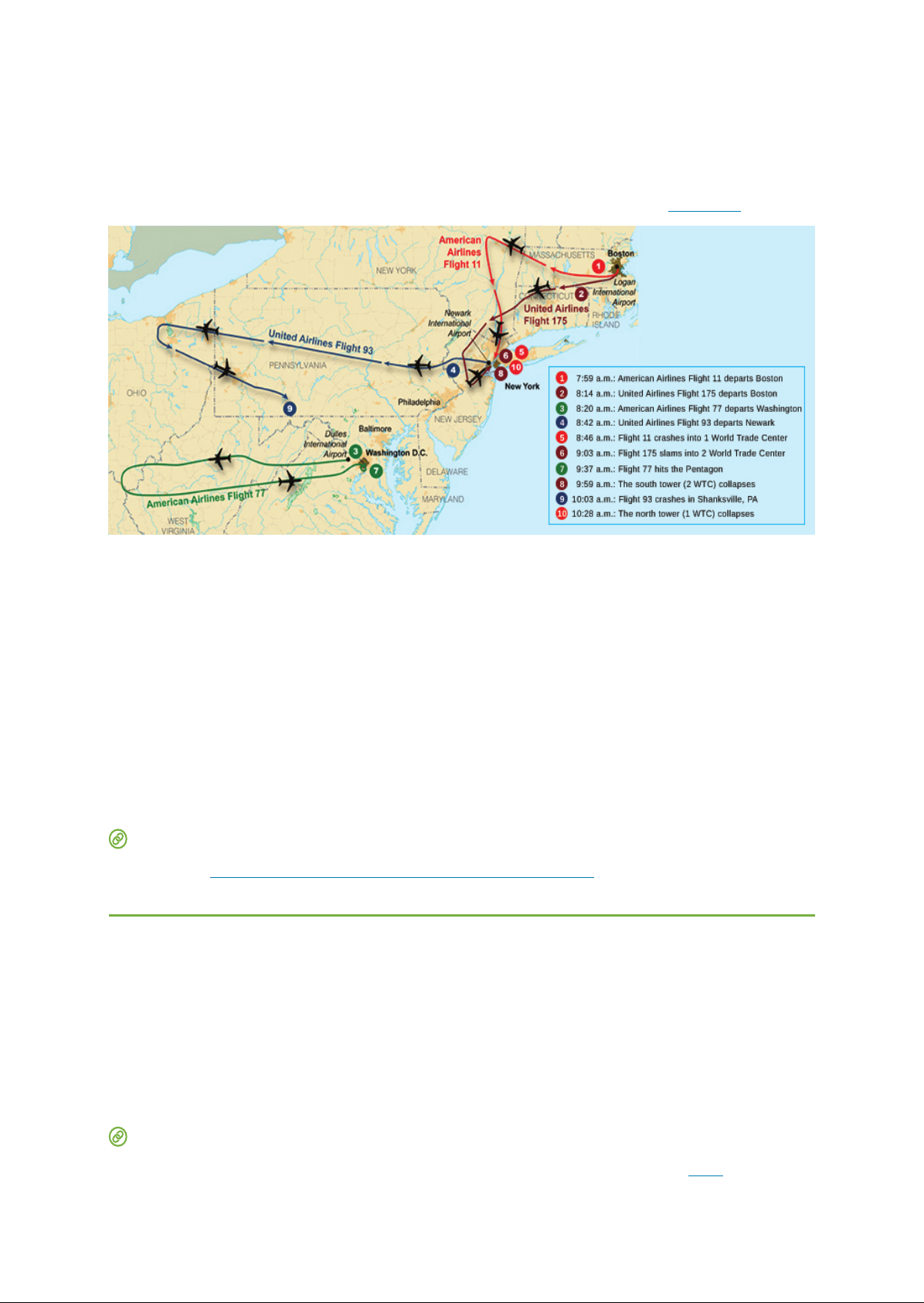

The War on Terror 879 towers collapsed . The third hijacked plane was into the Pentagon building in northern Virginia , just outside Washington , killing everyone on board and 125 people on the ground . The fourth plane , also heading towards Washington , crashed in a near , Pennsylvania , when passengers , aware of the other attacks , attempted to storm the cockpit and disarm the hijackers . Everyone on board was killed ( Figure ) American American rum . Airlines 71 departs Washington am Airlines Fight 93 Mann am . mac Comm Figh ( 175 stuns World Tilda Cams . run 77 hits are am we mum lower ( mo ) Am . 93 II . PA 1023 ! We norm ( i Am , mums ?

77 FIGURE Three of the four airliners hijacked on September 11 , 2001 , reached their targets . United 93 , presumably on its way to destroy either the Capitol or the White House , was brought down in a after a struggle between the passengers and the hijackers . That evening , President Bush promised the nation that those responsible for the attacks would be brought to justice . Three days later , Congress issued a joint resolution authorizing the president to use all means necessary against the individuals , organizations , or nations involved in the attacks . On September 20 , in an address to ajoint session , Bush declared war on terrorism , blamed leader Osama bin Laden for the attacks , and demanded that the radical Islamic fundamentalists who ruled Afghanistan , the Taliban , turn bin Laden over or face attack by the United States . This speech encapsulated what became known as the Bush Doctrine , the belief that the United States has the right to protect itself from terrorist acts by engaging in wars or ousting hostile governments in favor of friendly , preferably democratic , regimes . CLICK AND EXPLORE Read the text Bush address ( to Congress declaring a war on terror . World leaders and millions of their citizens expressed support for the United States and condemned the deadly attacks . Russian president Vladimir Putin characterized them as a bold challenge to humanity itself . German chancellor said the events of that day were not only attacks on the people in the United States , our friends in America , but also against the entire civilized world , against our own freedom , against our own values , values which we share with the American people . chairman of the Palestinian Liberation Organization and a veteran of several bloody struggles against Israel , was dumbfounded by the news and announced to reporters in Gaza , We completely condemn this very dangerous attack , and I convey my condolences to the American people , to the American president and to the American administration . CLICK AND EXPLORE In May 2014 , a Museum dedicated to the memory of the victims was completed . Watch this video

880 32 The Challenges of the Century and learn more about the victims and how the country seeks to remember them . GOING TO WAR IN AFGHANISTAN When it became clear that the mastermind behind the attack was Osama bin Laden , a wealthy Saudi Arabian national who ran his terror network from Afghanistan , the full attention of the United States turned towards Central Asia and the Taliban . Bin Laden had deep roots in Afghanistan . Like many others from around the Islamic world , he had come to the country to oust the Soviet army , which invaded Afghanistan in 1979 . Ironically , both bin Laden and the Taliban received material support from the United States at that time . By the late , the Soviets and the Americans had both left , although bin Laden , by that time the leader of his own terrorist organization , remained . The Taliban refused to turn bin Laden over , and the United States began a bombing campaign in October , allying with the Afghan Northern Alliance , a coalition of tribal leaders opposed to the Taliban . air support was soon augmented by ground troops ( Figure . By November 2001 , the Taliban had been ousted from power in Afghanistan capital of Kabul , but bin Laden and his followers had already escaped across the Afghan border to mountain sanctuaries in northern Pakistan . FIGURE Marines against Taliban forces in Province , Afghanistan . was a center of Taliban strength , credit ) IRAQ At the same time that the military was taking control of Afghanistan , the Bush administration was looking to a new and larger war with the country of Iraq . Relations between the United States and Iraq had been strained ever since the Gulf War a decade earlier Economic sanctions imposed on Iraq by the United Nations , and American attempts to foster internal revolts against President Saddam Hussein government , had further tainted the relationship . A faction within the Bush administration , sometimes labeled neoconservatives , believed Iraq recalcitrance in the face of overwhelming military superiority represented a dangerous symbol to terrorist groups around the world , recently emboldened by the dramatic success of the attacks in the United States . Powerful members of this faction , including Vice President Dick Cheney and Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld , believed the time to strike Iraq and solve this festering problem was right then , in the wake of . Others , like Secretary of State Colin Powell , a highly respected veteran of the Vietnam War and former chair of the Joint Chiefs of Staff , were more cautious about initiating combat . The more militant side won , and the argument for war was gradually laid out for the American people . The immediate impetus to the invasion , it argued , was the fear that Hussein was stockpiling weapons of mass destruction ( nuclear , chemical , or biological weapons capable of wreaking great havoc . Hussein had in fact used against Iranian forces during his war with Iran in the , and against the Kurds in northern Iraq in time when the United States actively supported the Iraqi dictator Following the Gulf War , Access for free at .

The War on Terror 881 inspectors from the United Nations Special Commission and International Atomic Energy Agency had in fact located and destroyed stockpiles of Iraqi weapons . Those arguing for a new Iraqi invasion insisted , however , that weapons still existed . President Bush himself told the nation in October 2002 that the United States was facing clear evidence of peril , we can not wait for the smoking could come in the form of a mushroom The head of the United Nations Monitoring , and Inspection Commission , dismissed these claims . argued that while Saddam Hussein was not being entirely forthright , he did not appear to be in possession of . Despite and his own earlier misgivings , Powell argued in 2003 before the United Nations General Assembly that Hussein had violated UN resolutions . Much of his evidence relied on secret information provided by an informant that was later proven to be false . On March 17 , 2003 , the United States cut off all relations with Iraq . Two days later , in a coalition with Great Britain , Australia , and Poland , the United States began Operation Iraqi Freedom with an invasion of Iraq . Other arguments supporting the invasion noted the ease with which the operation could be accomplished . In February 2002 , some in the Department of Defense were suggesting the war would be a cakewalk . In November , referencing the short and successful Gulf War of , Secretary of Defense Rumsfeld told the American people it was absurd , as some were claiming , that the would degenerate into a long , quagmire . Five days or weeks or months , but it certainly is going to last any longer than that , he insisted . It wo be a World War III . And , just days before the start of combat operations in 2003 , Vice President Cheney announced that forces would likely be greeted as liberators , and the war would be over in weeks rather than Early in the , these predictions seemed to be coming true . The march into Baghdad went fairly smoothly . Soon Americans back home were watching on television as soldiers and the Iraqi people worked together to topple statues of the deposed leader Hussein around the capital . The reality , however , was far more complex . While American deaths had been few , thousands of Iraqis had died , and the seeds of internal strife and resentment against the United States had been sown . The United States was not prepared for a long period of occupation it was also not prepared for the inevitable problems of law and order , or for the violent sectarian that emerged . Thus , even though Bush proclaimed a victory in May 2003 , on the deck of the USS Abraham Lincoln with the banner Mission Accomplished prominently displayed behind him , the celebration proved premature by more than seven years ( Figure . FIGURE President Bush gives the victory symbol on the aircraft carrier USS Abraham Lincoln in May 2003 , after American troops had completed the capture of Iraq capitol Baghdad . Yet , by the time the United States withdrew its forces from Iraq in 2011 , nearly thousand , soldiers had died .

882 32 The Challenges of the Century MY STORY General James Conway on the Invasion of Baghdad General James Conway , who commanded the First Marine Expeditionary Force in Iraq , answers a questions about civilian casualties during the 2003 invasion of Baghdad . As a civilian in those early days , one had the sense that the high command had expected something to happen which didn . Was that a correct perception ?

were told by our intelligence folks that the enemy is carrying civilian clothes in their packs because , as soon as the shooting starts , they going put on their civilian clothes and they going go home . Well , they put on their civilian clothes , but not to go home . They put on civilian clothes to blend with the civilians and shoot back at us . There been some criticism of the behavior of the Marines at the bridge across the Tigris River into Baghdad in terms of civilian casualties . after the Third Battalion , Fourth Marines crossed , the resistance was not all gone . They had just fought to take a bridge . They were being counterattacked by enemy forces . Some of the civilian vehicles that wound up with the bullet holes in them contained enemy in uniform with weapons , some of them did not . Again , we terribly sorry about the loss of any civilian life where civilians are killed in a setting . I will guarantee you , it was not the intent of those Marines to kill civilians . The civilian casualties happened because the Marines felt threatened , and they were having a tough time an enemy that is violating the laws of land warfare by going to civilian clothes , putting his own people at risk . All of those things , I think , had an impact on the behavior of the Marines , and in the end it very unfortunate that civilians died . Who in your opinion bears primary responsibility for the deaths of Iraqi civilians ?

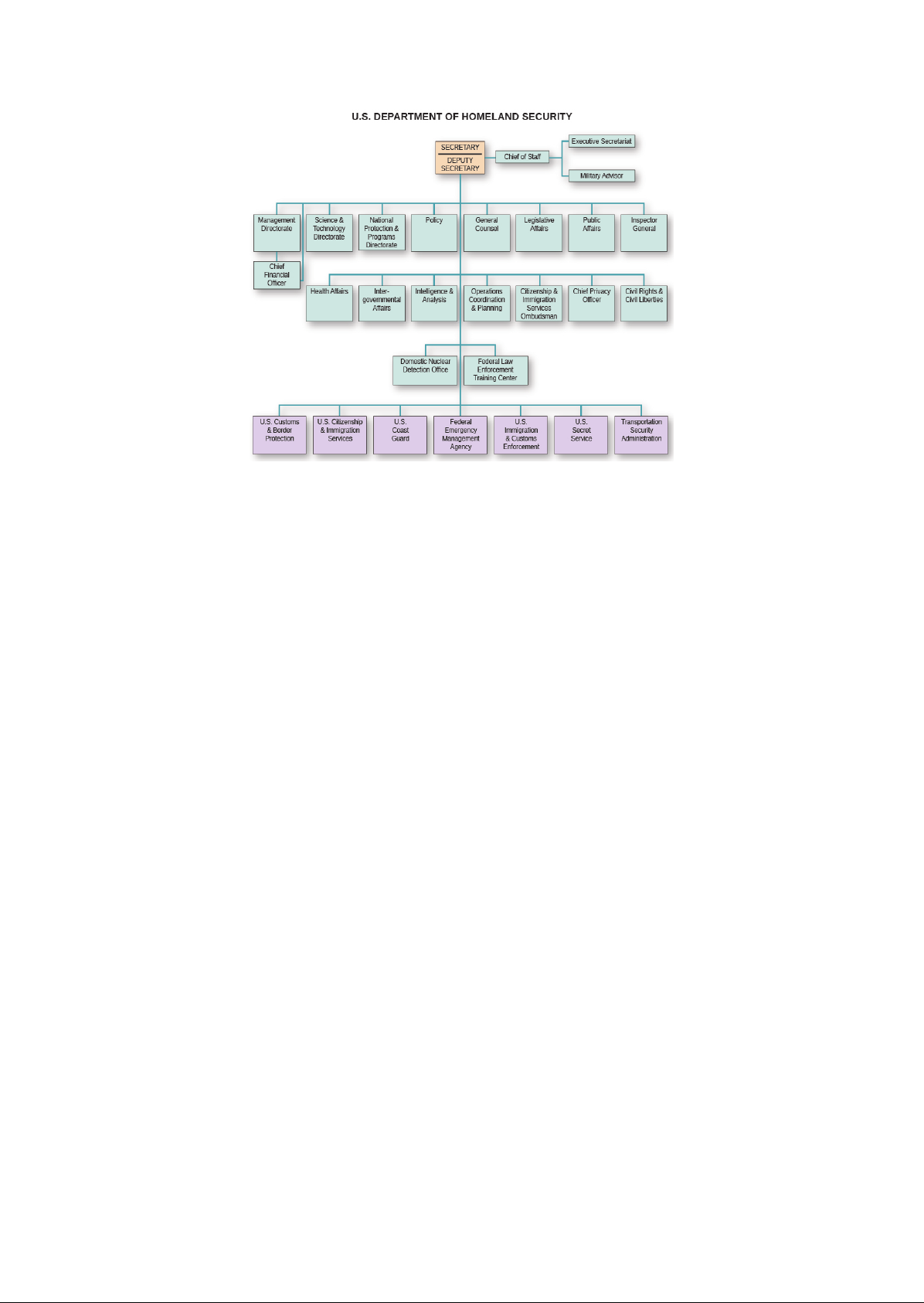

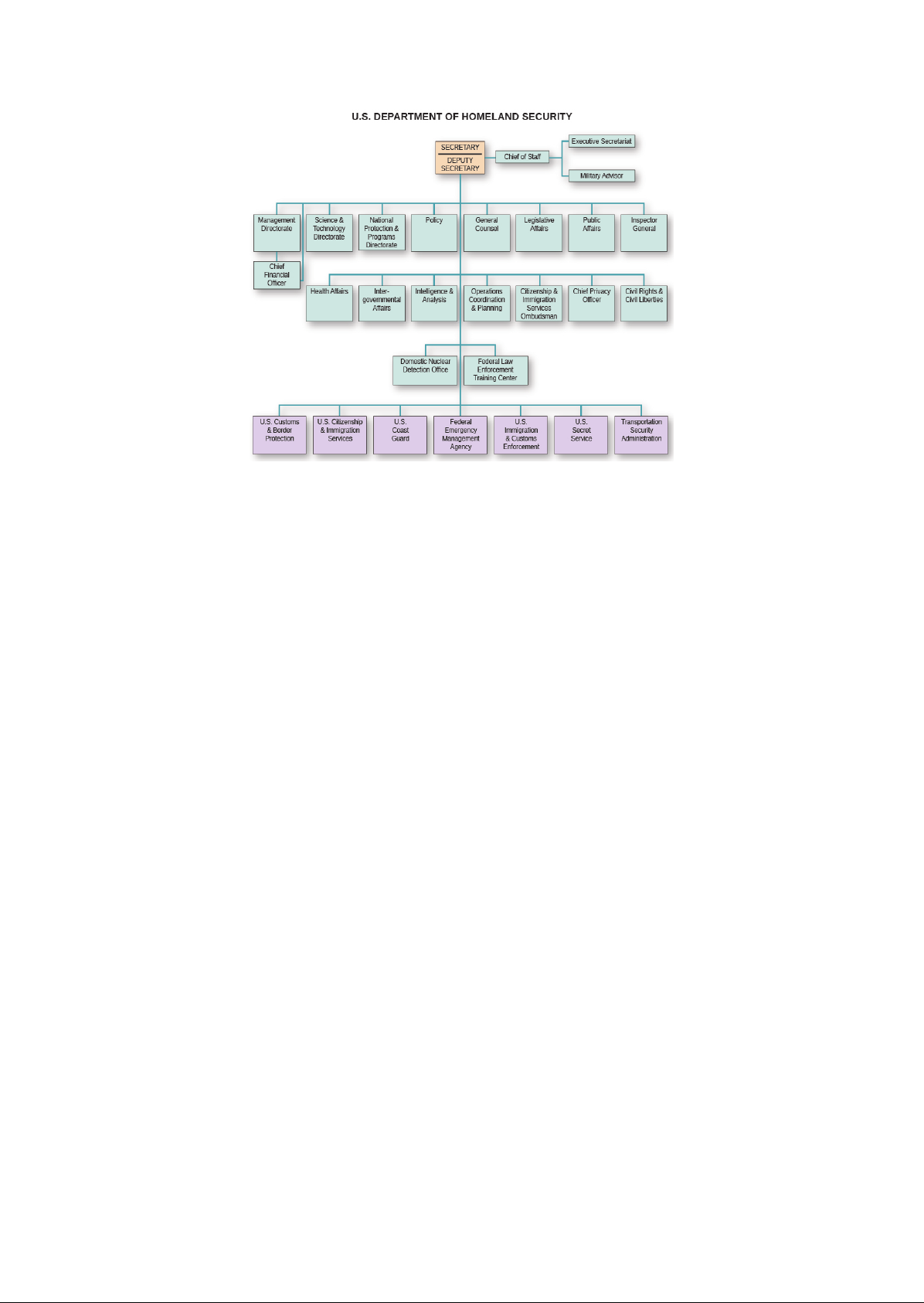

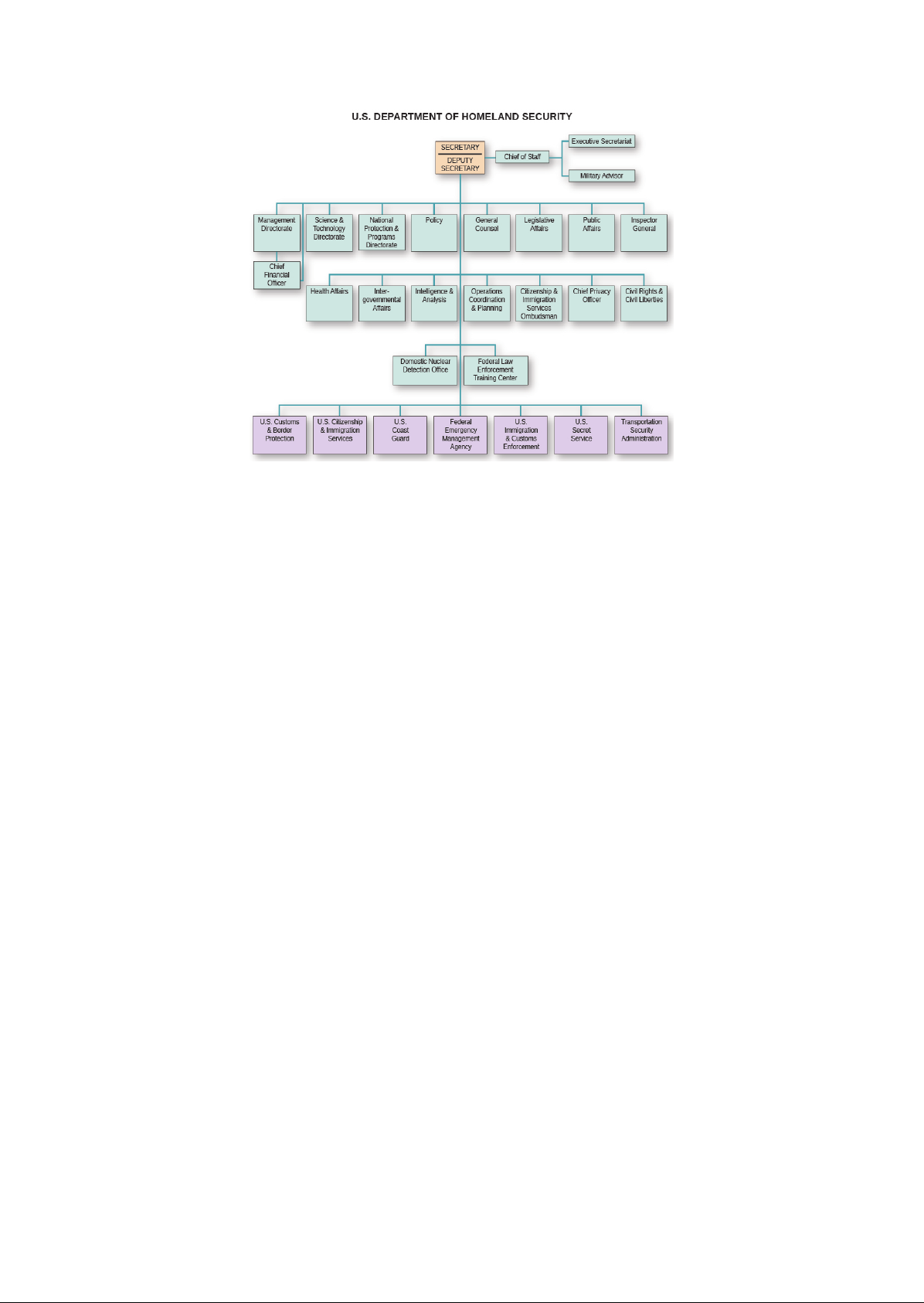

DOMESTIC SECURITY The attacks of September 11 awakened many to the reality that the end of the Cold War did not mean an end to foreign violent threats . Some Americans grew wary of alleged possible enemies in their midst and hate crimes against Muslim those thought to be in the aftermath . Fearing that terrorists might strike within the nation borders again , and aware of the chronic lack of cooperation among different federal law enforcement agencies , Bush created the of Homeland Security in October 2001 . The next year , Congress passed the Homeland Security Act , creating the Department of Homeland Security , which centralized control over a number of different government functions in order to better control threats at home Figure . The Bush administration also pushed the USA Patriot Act through Congress , which enabled law enforcement agencies to monitor citizens and phone conversations without a warrant . Access for free at .

The War on Terror DEPARTMENT OF HOMELAND SECURITY Secretarial at Sat ! Management Legislative Public . Counsel Geneva ! Health inter a ! ow . Coordination ow Mains a Federal Law Damian om Center a Burner Coast I Secret Seam ! Guam a Service Aw ?

I FIGURE The Department of Homeland Security was many duties , including guarding borders and , as this organizational chart shows , wielding contro over the Coast Guard , he Secret Service , Customs , and a multitude of other law enforcement agencies . The Bush administration was committed to rooting out to the United States wherever they originated , and in the weeks after September 11 , the Central Intelligence Agency ( CIA ) scoured the globe , sweeping up thousands ofyoung Muslim men . Because law the use of torture , the CIA transferred some of these prisoners to other practice known as rendition or extraordinary the local authorities can use methods of interrogation not allowed in the United States . While the CIA operates overseas , the Federal Bureau of Investigation ( FBI ) is the chief federal law enforcement agency within national borders . Its activities are limited by , among other things , the Fourth Amendment , which protects citizens against unreasonable searches and seizures . Beginning in 2002 , however , the Bush administration implemented a program of warrantless domestic wiretapping , known as the Terrorist Surveillance Program , by the National Security Agency ( NSA ) The shaky constitutional basis for this program was ultimately revealed in August 2006 , when a federal judge in Detroit ordered the program ended immediately . The use of unconstitutional wire taps to prosecute the war on terrorism was only one way the new threat challenged authorities in the United States . Another problem was deciding what to do with foreign terrorists captured on the in Afghanistan and Iraq . In traditional , where both sides are uniformed combatants , the rules of engagement and the treatment of prisoners of war are clear . But in the new war on terror , extracting intelligence about upcoming attacks became a top priority that superseded human rights and constitutional concerns . For that purpose , the United States began transporting men suspected of being members of to the naval base at Guantanamo Bay , Cuba , for questioning . The Bush administration labeled the detainees unlawful combatants , in an effort to avoid affording them the rights guaranteed to prisoners of war , such as protection from torture , by international treaties such as the Geneva Conventions . Furthermore , the Justice Department argued that the prisoners were unable to sue for their rights in courts on the grounds that the constitution did not apply to territories . It was only in 2006 that the Supreme Court ruled in Rumsfeld that the military tribunals that tried Guantanamo prisoners violated both federal law and the Geneva Conventions . 883

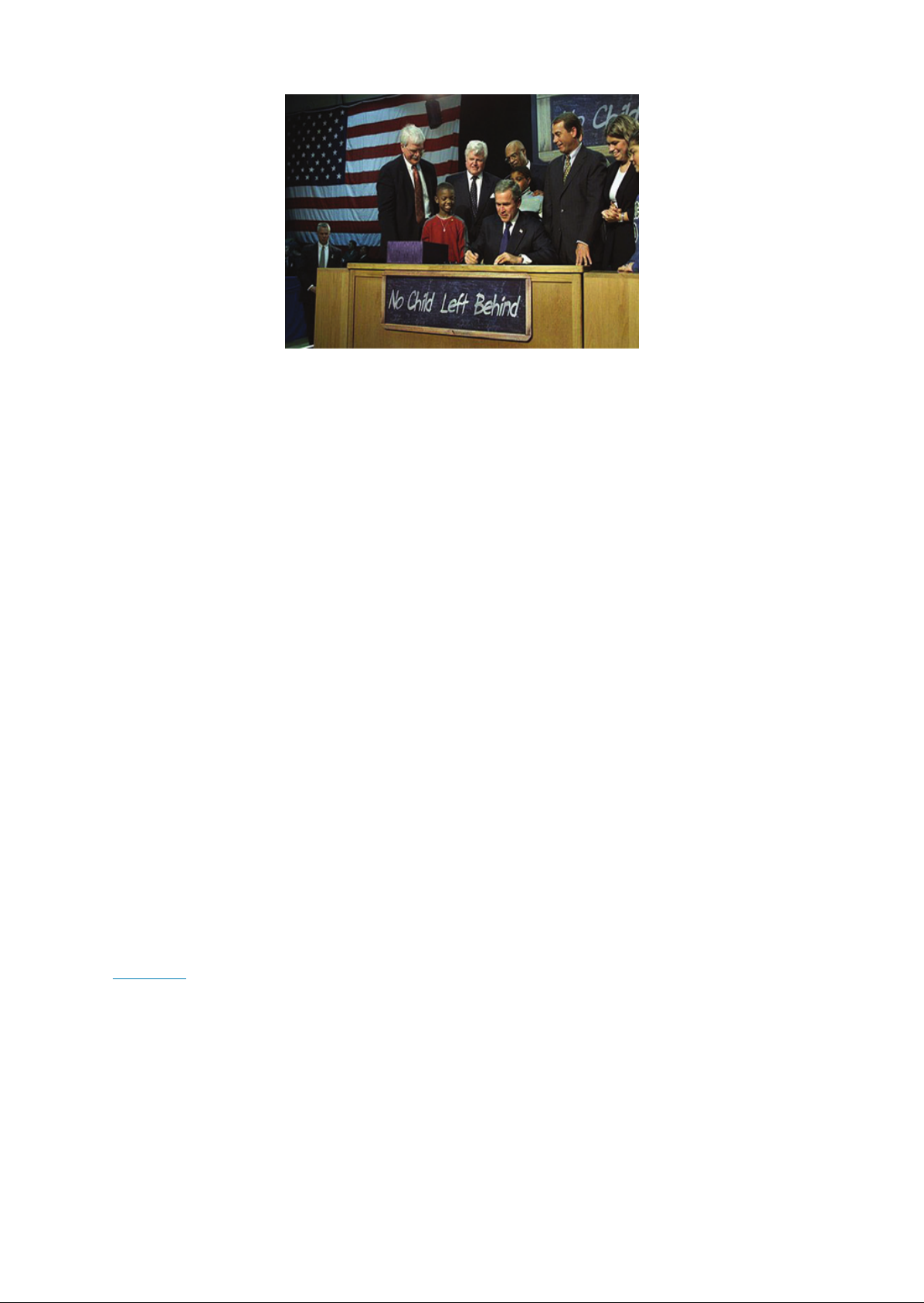

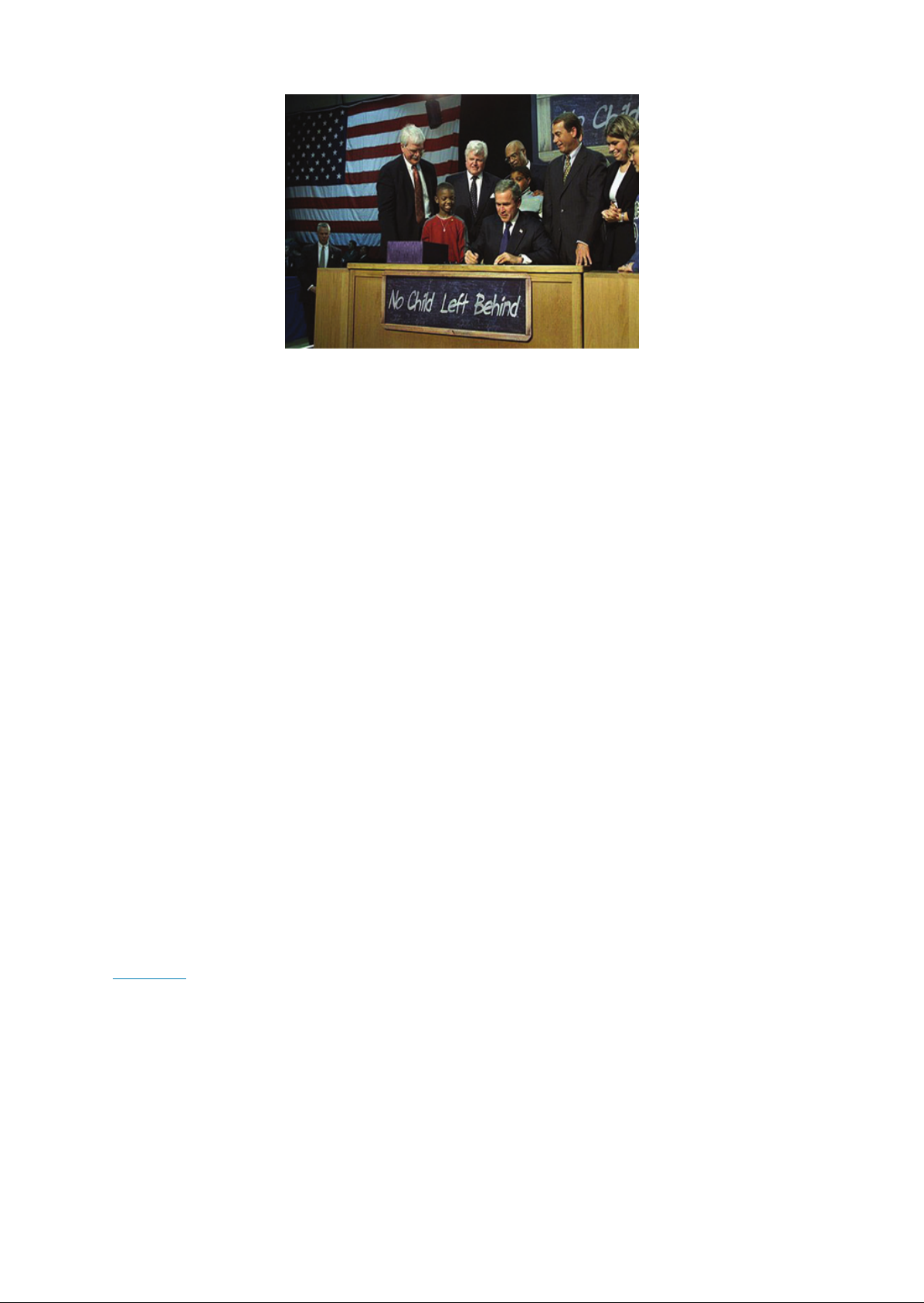

884 32 The Challenges of the Century The Domestic Mission LEARNING OBJECTIVES By the end ofthis section , you will be able to Discuss the Bush administration economic theories and tax policies , and their effects on the American economy Explain how the federal government attempted to improve the American public education system Describe the federal government response to Hurricane Katrina Identify the causes of the Great Recession of 2008 and its effect on the average citizen By the time George Bush became president , the concept of economics had become an article of faith within the Republican Party . The argument was that tax cuts for the wealthy would allow them to invest more and create jobs for everyone else . This belief in the powers of competition also served as the foundation of Bush education reform . But by the end of 2008 , however , Americans faith in the dynamics of the free market had been badly shaken . The failure of the homeland security apparatus during Hurricane Katrina and the ongoing challenge of the Iraq War compounded the effects of the bleak economic situation . OPENING AND CLOSING THE GAP The Republican Party platform for the 2000 election offered the American people an opportunity to once again test the rosy expectations of economics . In 2001 , Bush and the Republicans pushed through a trillion tax cut by lowering tax rates across the board but reserving the largest cuts for those in the highest tax brackets . This was in the face of calls by Republicans for a balanced budget , which Bush insisted would happen when the job creators expanded the economy by using their increased income to invest in business . The cuts were controversial the rich were getting richer while the middle and lower classes bore a proportionally larger share of the nation tax burden . Between 1966 and 2001 , of the nation income gained from increased productivity went to the top percent of earners . By 2005 , dramatic examples of income inequity were increasing the chief executive of earned 15 million that year , roughly 950 times what the companys average associate made . The head of the construction company . Homes made 150 million , or four thousand times what the average construction worker earned that same year . Even as productivity climbed , workers incomes stagnated with a larger share of the wealth , the very rich further their on public policy . Left with a smaller share of the economic pie , average workers had fewer resources to improve their lives or contribute to the nation prosperity by , for example , educating themselves and their children . Another gap that had been widening for years was the education gap . Some education researchers had argued that American students were being left behind . In 1983 , a commission established by Ronald Reagan had published a sobering assessment of the American educational system entitled A Nation at Risk . The report argued that American students were more poorly educated than their peers in other countries , especially in areas such as math and science , and were thus unprepared to compete in the global marketplace . Furthermore , test scores revealed serious educational achievement gaps between White students and students of color Touting himself as the education president , Bush sought to introduce reforms that would close these gaps . administration offered two potential solutions to these problems . First , it sought to hold schools accountable for raising standards and enabling students to meet them . The No Child Left Behind Act , signed into law in January 2002 , erected a system of testing to measure and ultimately improve student performance in reading and math at all schools that received federal funds Figure ) Schools whose students performed poorly on the tests would be labeled in need of improvement . performance continued , schools could face changes in curricula and teachers , or even the prospect of closure . Access for free at .

The Domestic Mission 885 FIGURE President Bush signed the No Child Left Behind Act into law in January 2002 . The act requires school systems to set high standards for students , place highly teachers in the classroom , and give military recruiters contact information for students . The second proposed solution was to give students the opportunity to attend schools with better performance records . Some of these might be charter schools , institutions funded by local tax monies in much the same way as public schools , but able to accept private donations and exempt from some of the rules public schools must follow . During the administration of George Bush , the development of charter schools had gathered momentum , and the American Federation of Teachers welcomed them as places to employ innovative teaching methods or offer specialized instruction in particular subjects . President George Bush now encouraged states to grant educational funding vouchers to parents , who could use them to pay for a private education for their children if they chose . These vouchers were funded by tax revenue that would otherwise have gone to public schools . THE 2004 ELECTION AND BUSH SECOND TERM In the wake of the attacks , Americans had rallied around their president in a gesture of patriotic loyalty , giving Bush approval ratings of 90 percent . Even following the few months of the Iraq war , his approval rating remained historically high at approximately 70 percent . But as the 2004 election approached , opposition to the war in Iraq began to grow . While Bush could boast of a number of achievements at home and abroad during his term , the narrow victory he achieved in 2000 poorly for his chances for reelection in 2004 and a successful second term . Reelection As the 2004 campaign ramped up , the president was persistently dogged by rising criticism of the violence of the Iraq war and the fact that his administration claims of had been greatly overstated . In the end , no such weapons were ever found . These criticisms were by growing international concern over the treatment of prisoners at the Guantanamo Bay detention camp and widespread disgust over the torture conducted by troops at the prison in Abu , Iraq , which surfaced only months before the election Figure .

886 32 The Challenges of the Century FIGURE The twenty captives were processed at the Guantanamo Bay detention camp on January 11 , 2002 ( a ) From late 2003 to early 2004 , prisoners held in Abu , Iraq , were tortured and humiliated in a variety of ways ( soldiers jumped on and beat them , led them on leashes , made them pose naked , and urinated on them . The release of photographs of the abuse raised an outcry around the world and greatly diminished the already flagging support for American intervention in Iraq . In March 2004 , an ambush by Iraqi insurgents of a convoy of private military contractors from Blackwater USA in the town of Fallujah west of Baghdad , and the subsequent torture and mutilation of the four captured mercenaries , shocked the American public . But the event also highlighted the growing insurgency against occupation , the escalating sectarian between the newly empowered Shia Muslims and the minority of the formerly ruling Sunni , and the escalating costs of a war involving a large number of private contractors that , by conservative estimates , approached trillion by 2013 . Just as importantly , the American campaign in Iraq had diverted resources from the war against in Afghanistan , where troops were no closer to capturing Osama bin Laden , the mastermind behind the attacks . With two hot wars overseas , one of which appeared to be spiraling out of control , the Democrats nominated a decorated Vietnam War veteran , Massachusetts senator John Kerry ( Figure , to challenge Bush for the presidency . As someone with combat experience , three Purple Hearts , and a foreign policy background , Kerry seemed like the right challenger in a time of war . But his record of support for the invasion of Iraq made his criticism of the incumbent less compelling and earned him the byname from Republicans . The Bush campaign also sought to characterize Kerry as an elitist out of touch with regular had studied overseas , spoke French , and married a wealthy heiress . Republican supporters also unleashed an attack on Kerry Vietnam War record , falsely claiming he had lied about his experience and fraudulently received his medals . Kerry reluctance to embrace his past leadership of Vietnam Veterans Against the War weakened the enthusiasm of antiwar Americans while opening him up to criticisms from veterans groups . This combination compromised the impact of his challenge to the incumbent in a time of war . Access for free at .

The Domestic Mission 887 FIGURE John Kerry served in the Navy duringthe Vietnam War and represented Massachusetts in the US . Senate from 1985 to 2013 . Here he greets sailors from the USS Sampson . Kerry was sworn in as President Obama Secretary of State in 2013 . Urged by the Republican Party to stay the course with Bush , voters listened . Bush won another narrow victory , and the Republican Party did well overall , picking up four seats in the Senate and increasing its majority there to . In the House , the Republican Party gained three seats , adding to its majority there as well . Across the nation , most also went to Republicans , and Republicans dominated many state legislatures . Despite a narrow win , the president made a bold declaration in his first news conference following the election . I earned capital in this campaign , political capital , and nowl intend to spend The policies on which he chose to spend this political capital included the partial privatization of Social Security and new limits on damages in medical malpractice lawsuits . In foreign affairs , Bush promised that the United States would work towards ending tyranny in the world . But at home and abroad , the president achieved few of his goals . Instead , his second term in became associated with the persistent challenge of pacifying Iraq , the failure of the homeland security apparatus during Hurricane Katrina , and the most severe economic crisis since the Great Depression . A Failed Domestic Agenda The Bush administration had planned a series of reforms , but corruption , scandals , and Democrats in Congress made these goals hard to accomplish . Plans to convert Social Security into a market mechanism relied on the claim that demographic trends would eventually make the system unaffordable for the shrinking number of young workers , but critics countered that this was easily . Privatization , on the other hand , threatened to derail the mission of the New Deal welfare agency and turn it into a fee generator for stock brokers and Wall Street . Similarly unpopular was the attempt to abolish the estate tax . Labeled the death tax by its critics , its abolishment would have only the wealthiest percent . As a result of the 2003 tax cuts , the growing federal did not help make the case for Republicans . The nation faced another policy crisis when the House of Representatives approved a bill making the undocumented status of millions of immigrants a felony and criminalizing the act of employing or knowingly aiding undocumented immigrants . In response , millions of immigrants , along with other critics of the bill , took to the streets in protest . What they saw as the civil rights challenge of their generation , conservatives read as a dangerous challenge to law and national security . Congress eventually agreed on a massive of the Border Patrol and the construction of a fence along the border with Mexico , but the deep divisions over immigration and the status of up to twelve million undocumented immigrants remained unresolved .