Industrialization and the Rise of Big Business, 1870-1900

Explore the Industrialization and the Rise of Big Business, 1870-1900 study material pdf and utilize it for learning all the covered concepts as it always helps in improving the conceptual knowledge.

Industrialization and the Rise of Big Business, 1870-1900 PDF Download

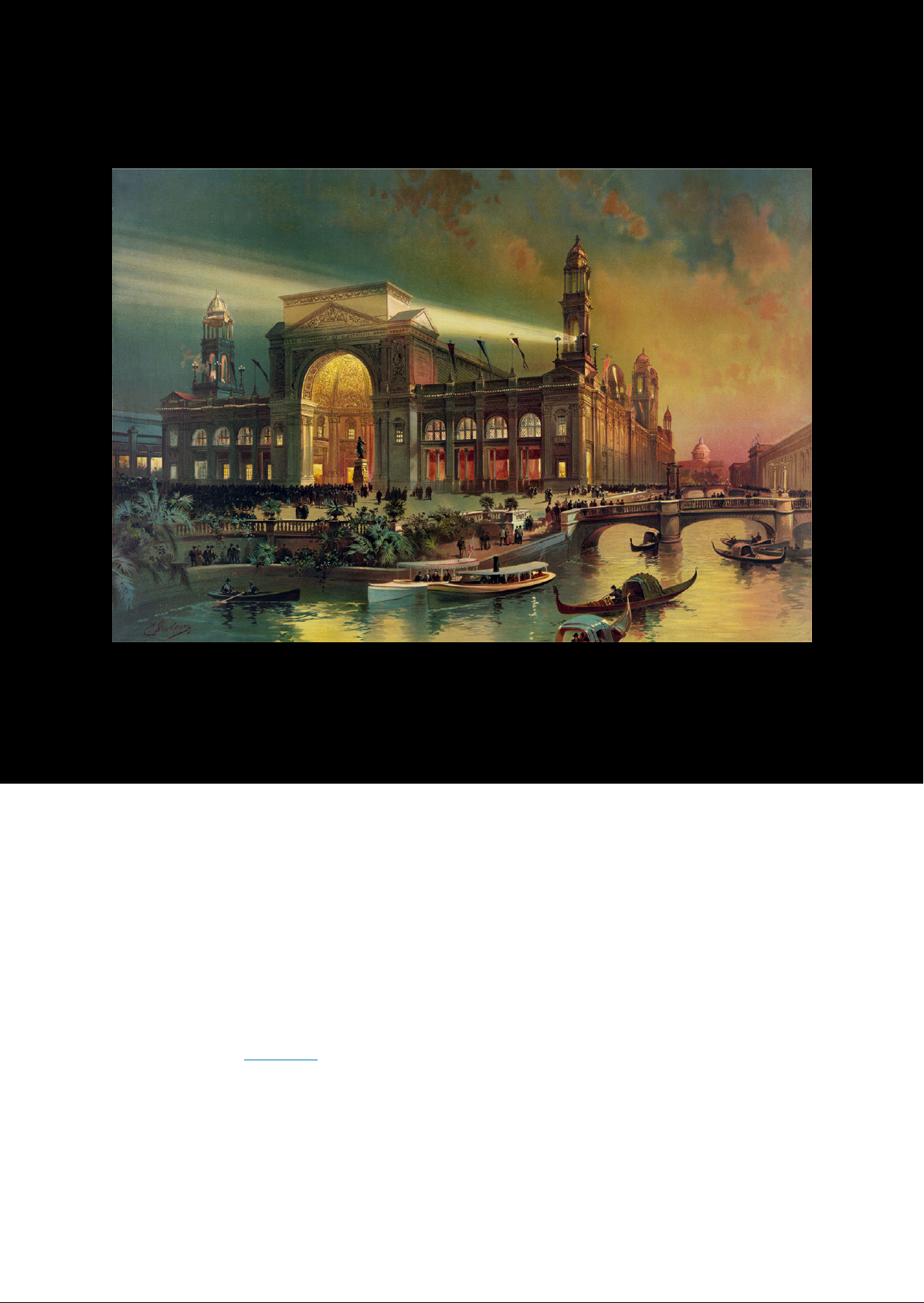

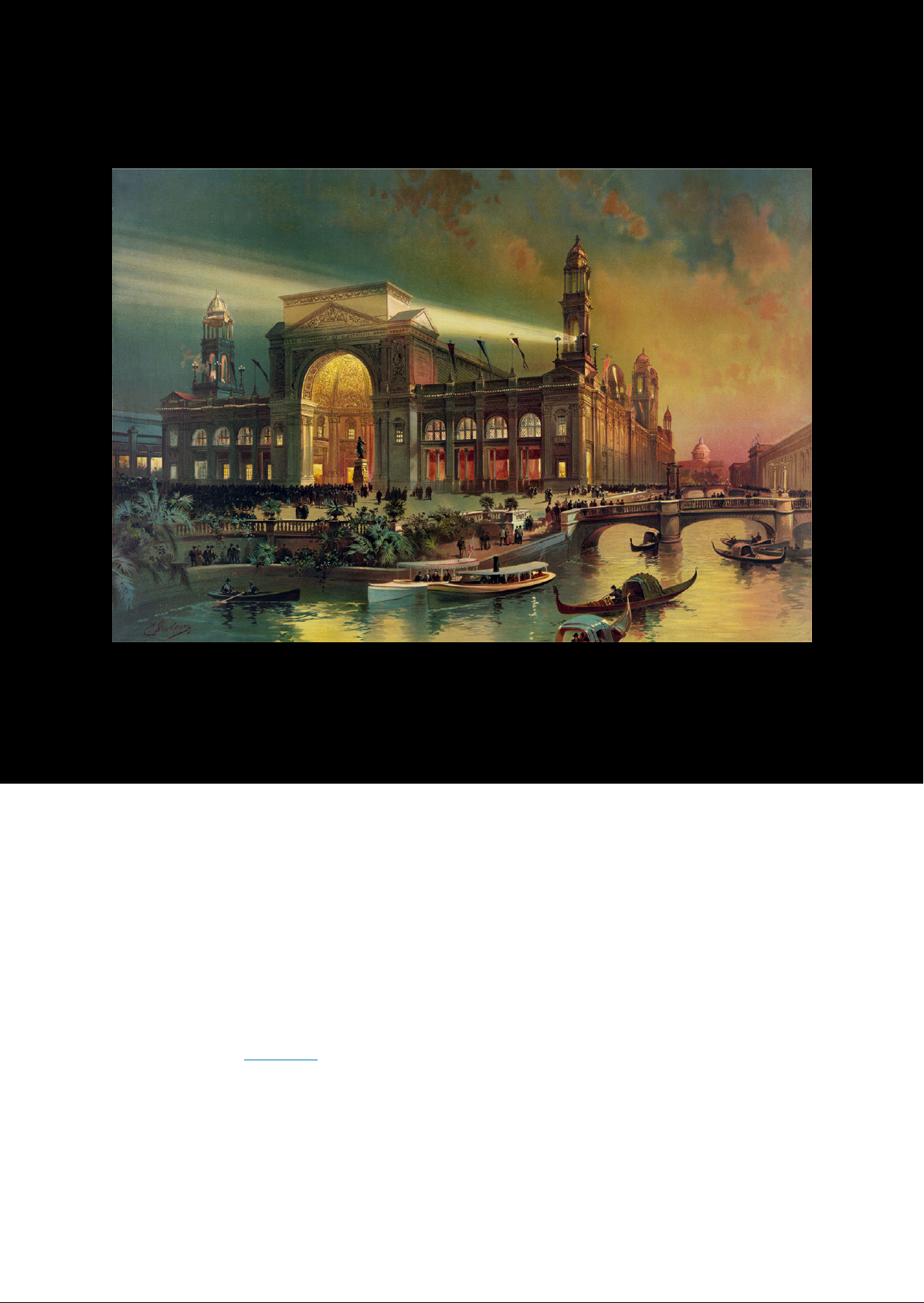

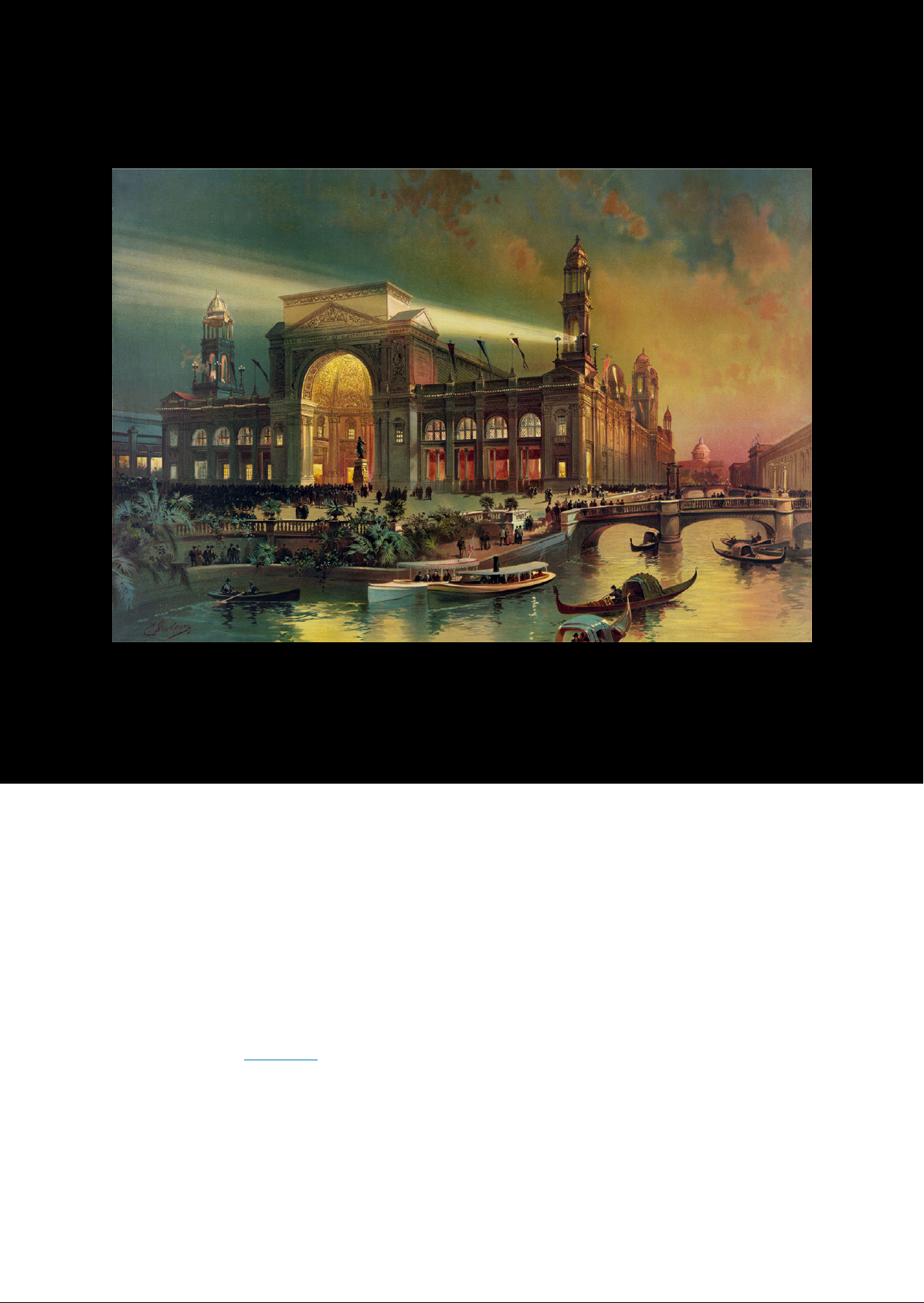

Industrialization and the Rise of Big Business , Ill FIGURE The Electrical Building , constructed in 1892 for the World Columbian Exposition , included displays from General Electric and , and introduced the American public to alternating current and neon lights . The Chicago World Fair , as the universal exposition was more commonly known , featured architecture , inventions , and design , serving as both a showcase for and an influence on the country optimism about the Industrial Age . CHAPTER OUTLINE Inventors of the Age From Invention to Industrial Growth Building Industrial America on the Backs of Labor A New American Consumer Culture INTRODUCTION The electric age was ushered into being in this last decade of the nineteenth century today when President Cleveland , by press a button , started the mighty machinery , rushing waters and revolving wheels in the World Columbian exhibition . With this announcement about the official start of the Chicago World Fair in 1893 ( Fiat ) the Salt Lake City Herald captured the excitement and optimism of the machine age . In the previous expositions , the editorial continued , the possibilities of electricity had been limited to the mere starting of the engines in the machinery hall , but in this it made thousands of servants do its bidding . the magic of electricity did the duty of the The fair , which the four hundredth anniversary of journey to America , was a potent symbol of the myriad inventions that changed American life and contributed to the

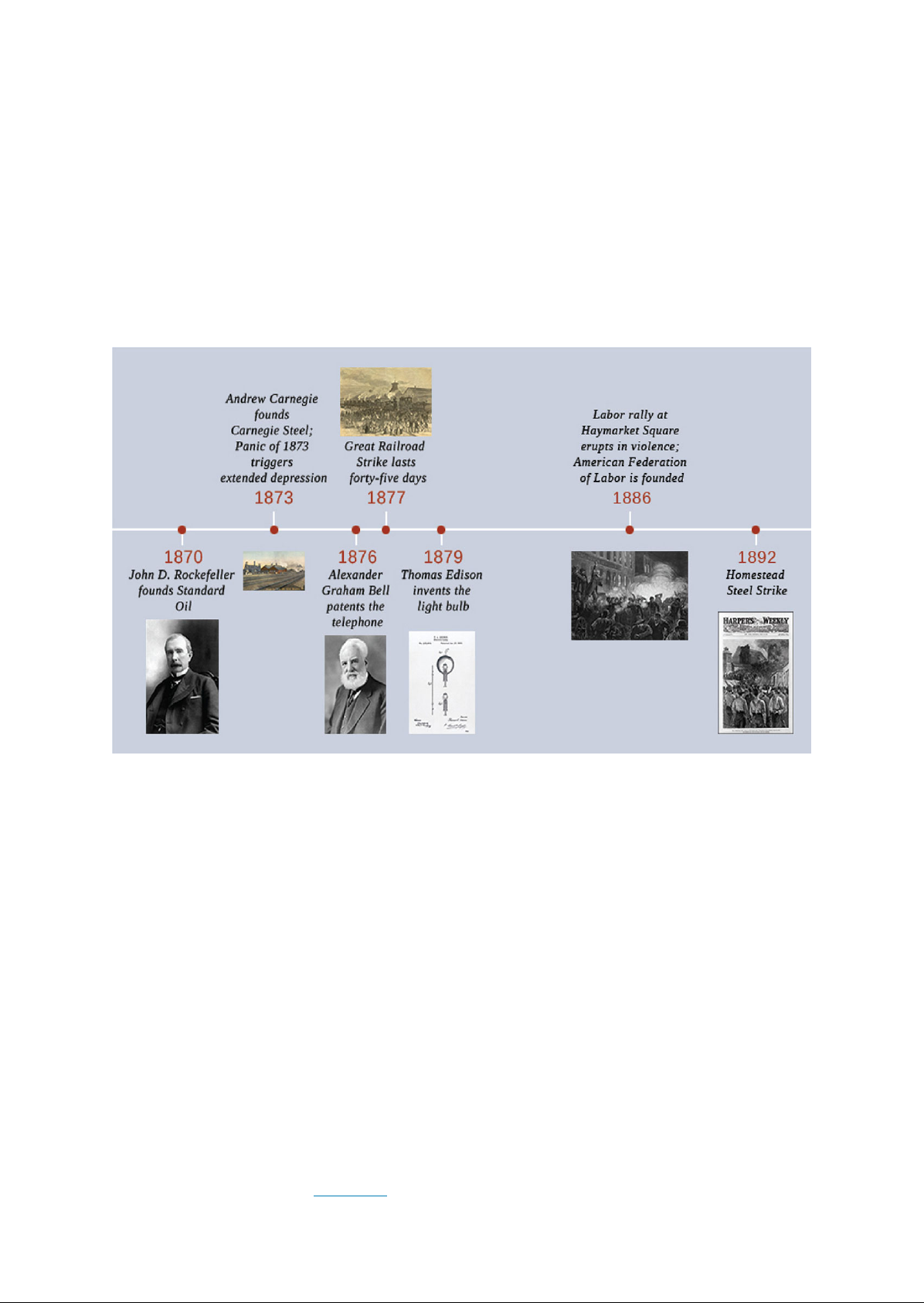

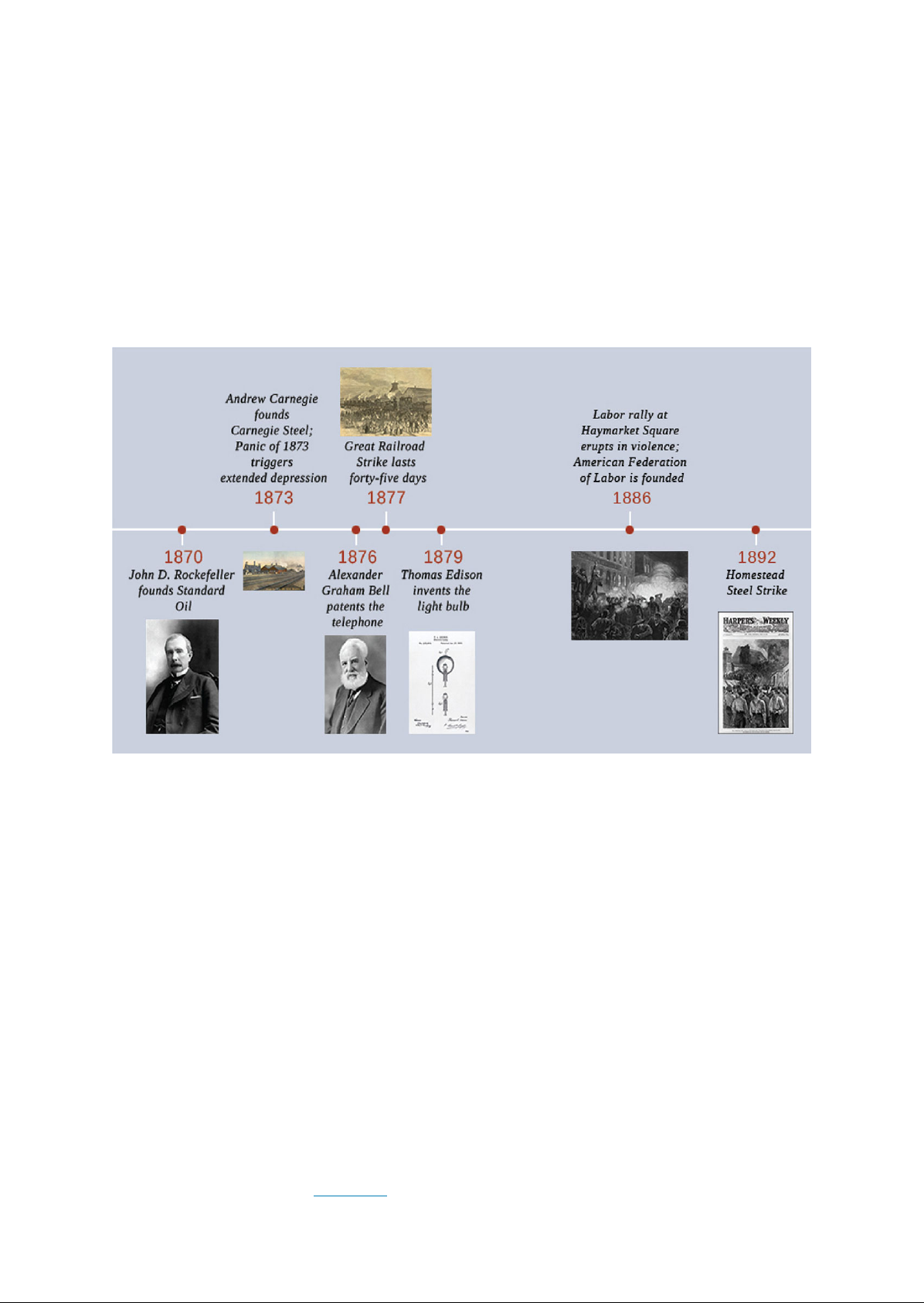

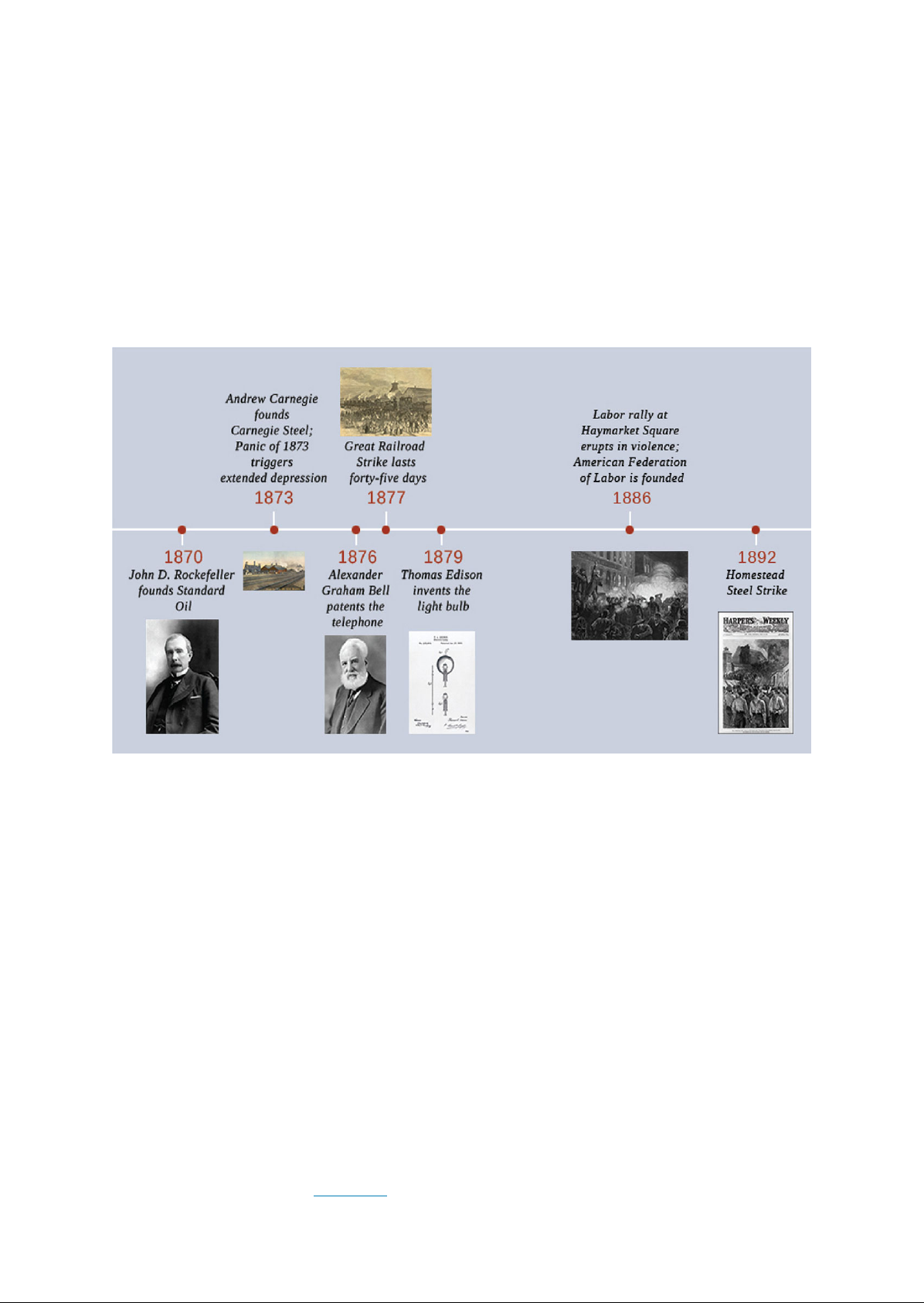

464 18 Industrialization and the Rise of Big Business , economic growth of the era , as well as the new wave of industrialization that swept the country . While businessmen capitalized upon such technological innovations , the new industrial working class faced enormous challenges . Ironically , as the World Fair welcomed its visitors , the nation was spiraling downward into the worst depression of the century . Subsequent frustrations among Americans laid the groundwork for the country labor movement . Inventors of the Age LEARNING OBJECTIVES By the end ofthis section , you will be able to Explain how the ideas and products of late inventors contributed to the rise of big business Explain how the inventions ofthe late nineteenth century changed everyday American life Carnegie Labor rally at Carnegie Steel Square Panic of 1873 Great Railroad erupts in violence triggers Strike lasts American Federation extended days of Labor is 1873 1877 1886 I 1870 1876 1879 1892 John Rockefeller Alexander Thomas Edison Homestead Standard Graham Bell invents the Steel strike Oil patents the light bulb telephone FIGURE The late nineteenth century was an energetic era of inventions and entrepreneurial spirit . Building upon the Industrial Revolution in Great Britain , as well as answering the increasing call from Americans for and comfort , the country found itself in the grip of invention fever , with more people working on their big ideas than ever before . In retrospect , harnessing the power of steam and then electricity in the nineteenth century vastly increased the power of man and machine , thus making other advances possible as the century progressed . Facing an increasingly complex everyday life , Americans sought the means by which to cope with it . Inventions often provided the answers , even as the inventors themselves remained largely unaware of the changing nature of their ideas . To understand the scope of this zeal for creation , consider the Patent , which , in decade of only 276 inventions . By 1860 , the had issued a total of patents . But between 1860 and 1890 , that number exploded to nearly , with another in the last decade of the century . While many of these patents came to naught , some inventions became in the rise of big business and the country move towards an economy , in which the desire for , comfort , and abundance could be more fully realized by most Americans . AN EXPLOSION OF INVENTIVE ENERGY From corrugated rollers that could crack hard , wheat into to refrigerated train cars and machines Figure , new inventions fueled industrial growth around the country . As Access for free at .

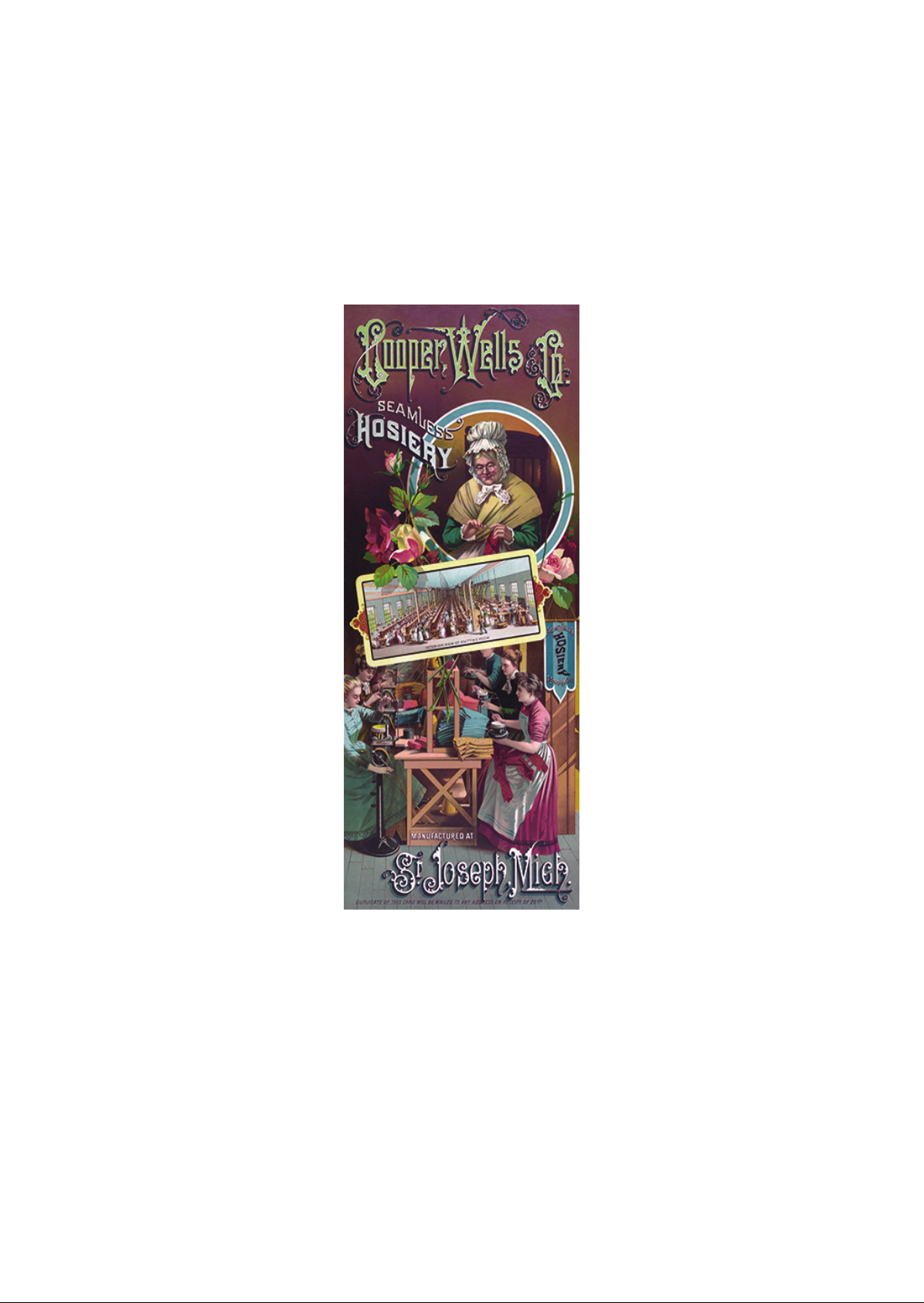

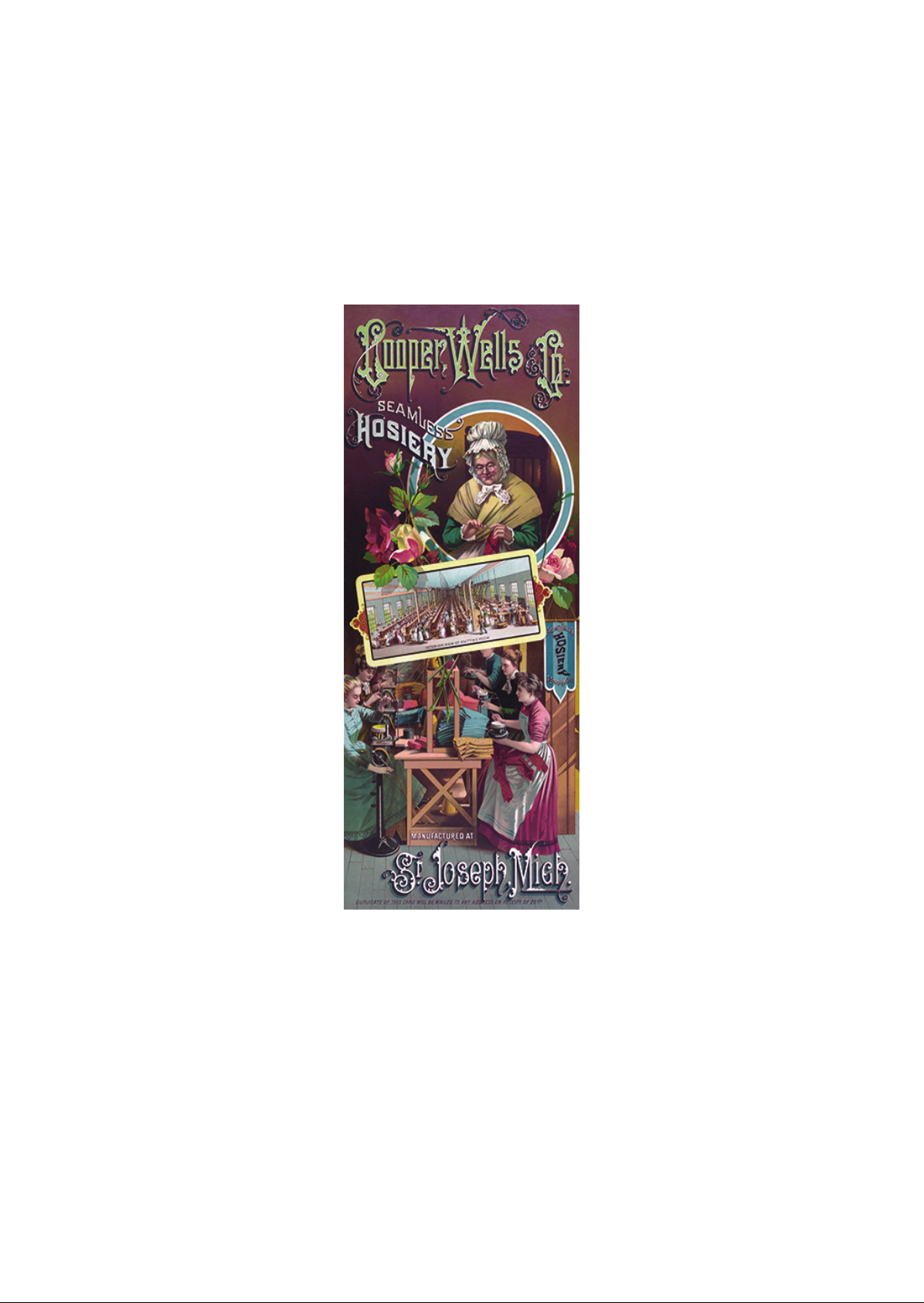

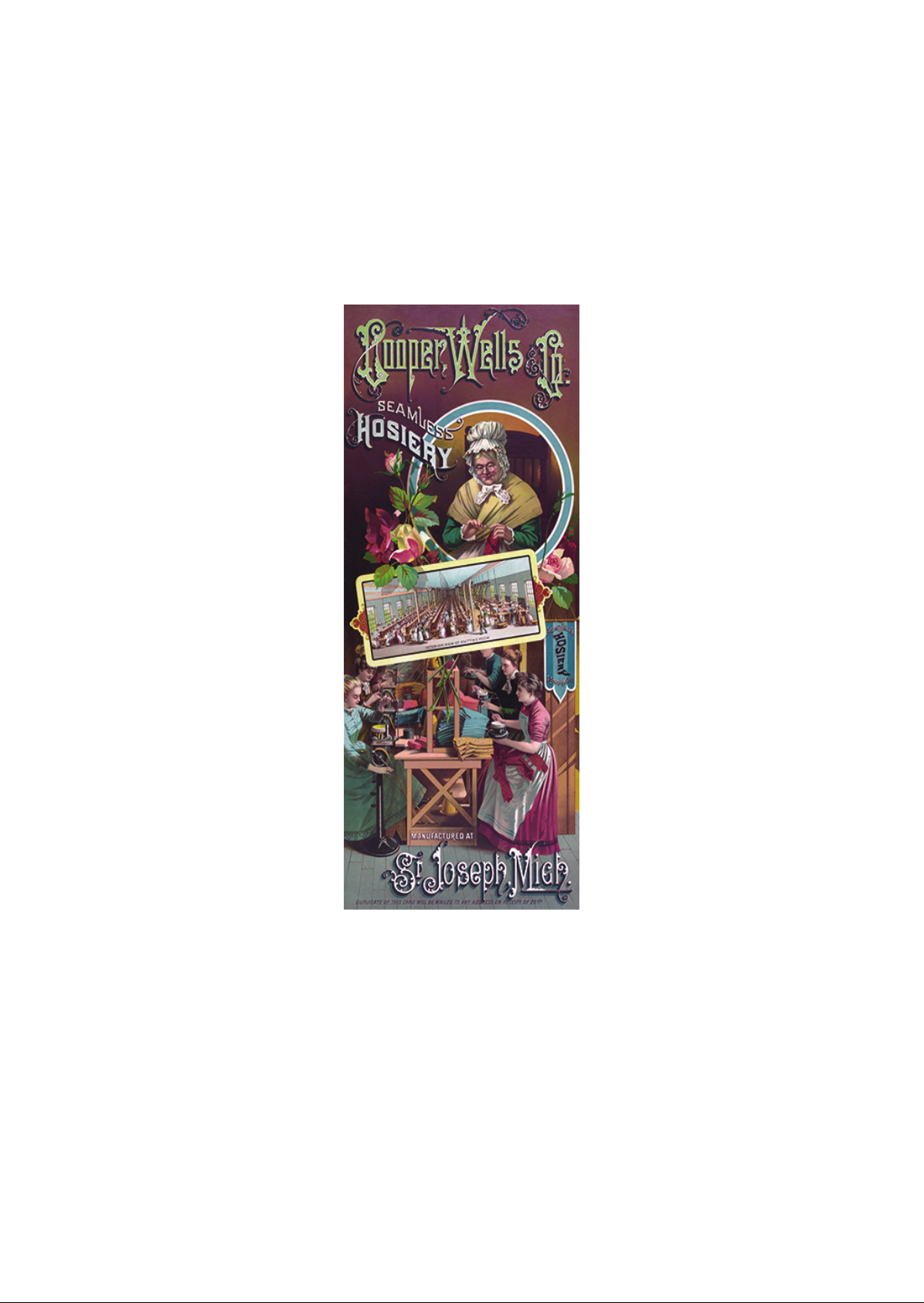

Inventors of the Age 465 late as 1880 , fully of all Americans still lived and worked on farms , whereas fewer than one in men , except for textile factories in which female employees tended to employed in factories . However , the development of commercial electricity by the close of the century , to complement the steam engines that already existed in many larger factories , permitted more industries to concentrate in cities , away from the previously essential water power In turn , newly arrived immigrants sought employment in new urban factories . Immigration , urbanization , and industrialization coincided to transform the face of American society from primarily rural to urban . From 1880 to 1920 , the number of industrial workers in the nation quadrupled from million to over 10 million , while over the same period urban populations doubled , to reach of the country total population . FIGURE Advertisements of the late nineteenth century promoted the higher quality and lower prices that people could expect from new inventions . Here , a knitting factory promotes the fact that its machines make seamless hose , while still traditional role of women in the garment industry , from grandmothers who used to sew by hand to young women who now used machines . In , worker productivity from the typewriter , invented in 1867 , the cash register , invented in 1879 , and the adding machine , invented in 1885 . These tools made it easier than ever to keep up with the rapid pace of business growth . Inventions also slowly transformed home life . The vacuum cleaner arrived during this era , as well as the toilet . These indoor water closets improved public health through the reduction in contamination associated with outhouses and their proximity to water supplies and homes . Tin cans and , later , Clarence experiments with frozen food , eventually changed how women shopped for , and prepared , food for their families , despite initial health concerns over preserved foods . With the advent of more easily prepared food , women gained valuable time in their daily schedules , a step that partially laid the

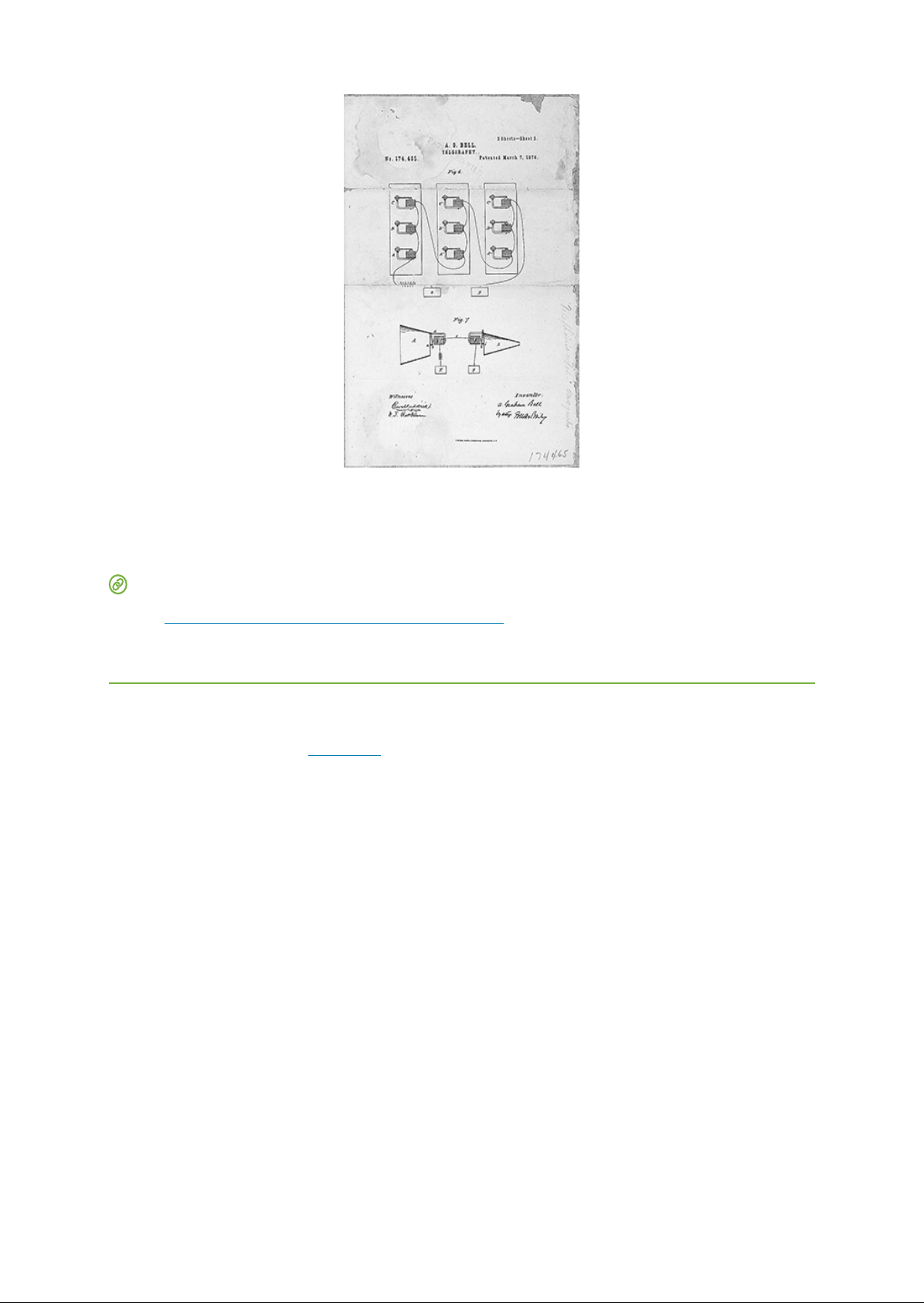

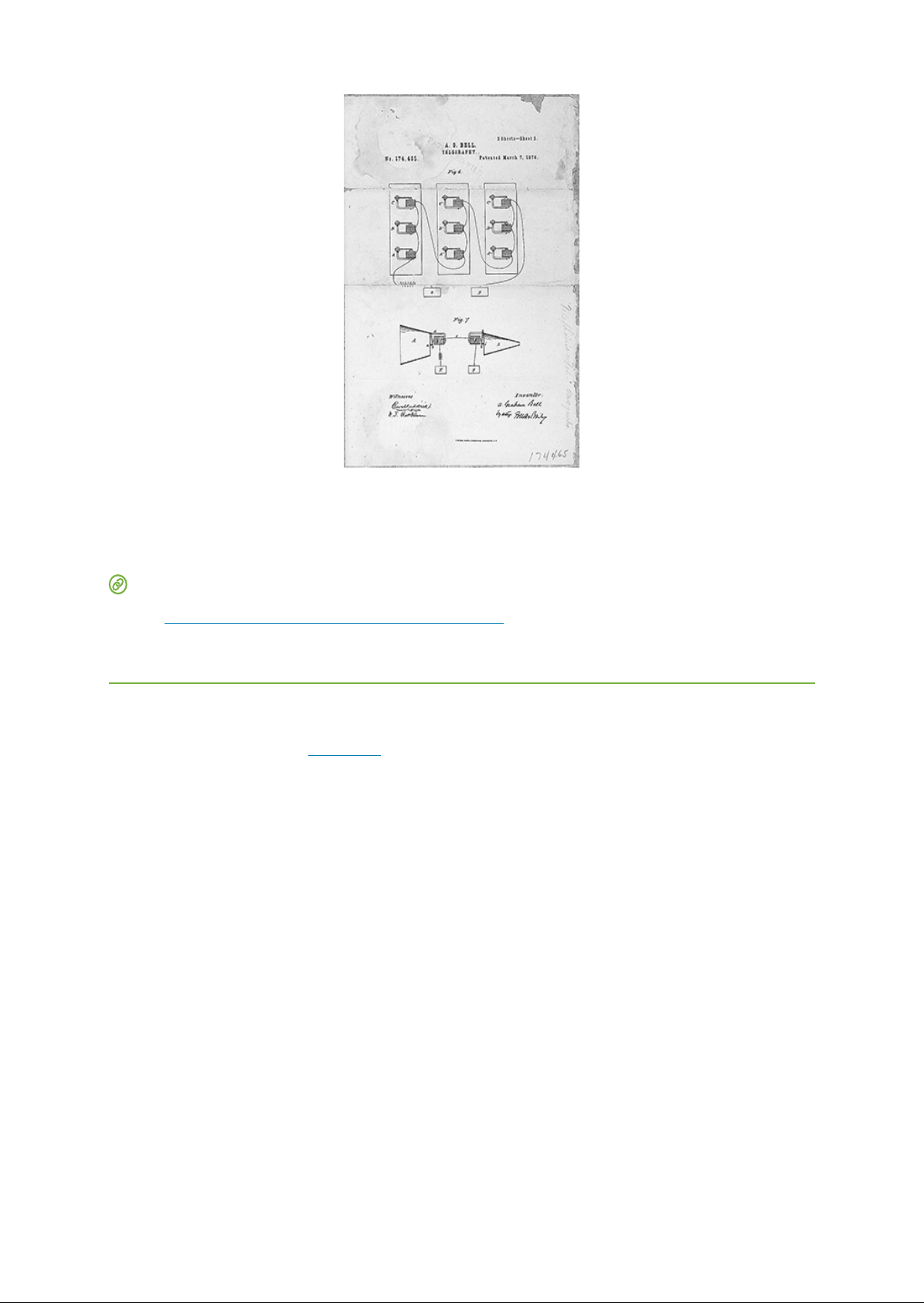

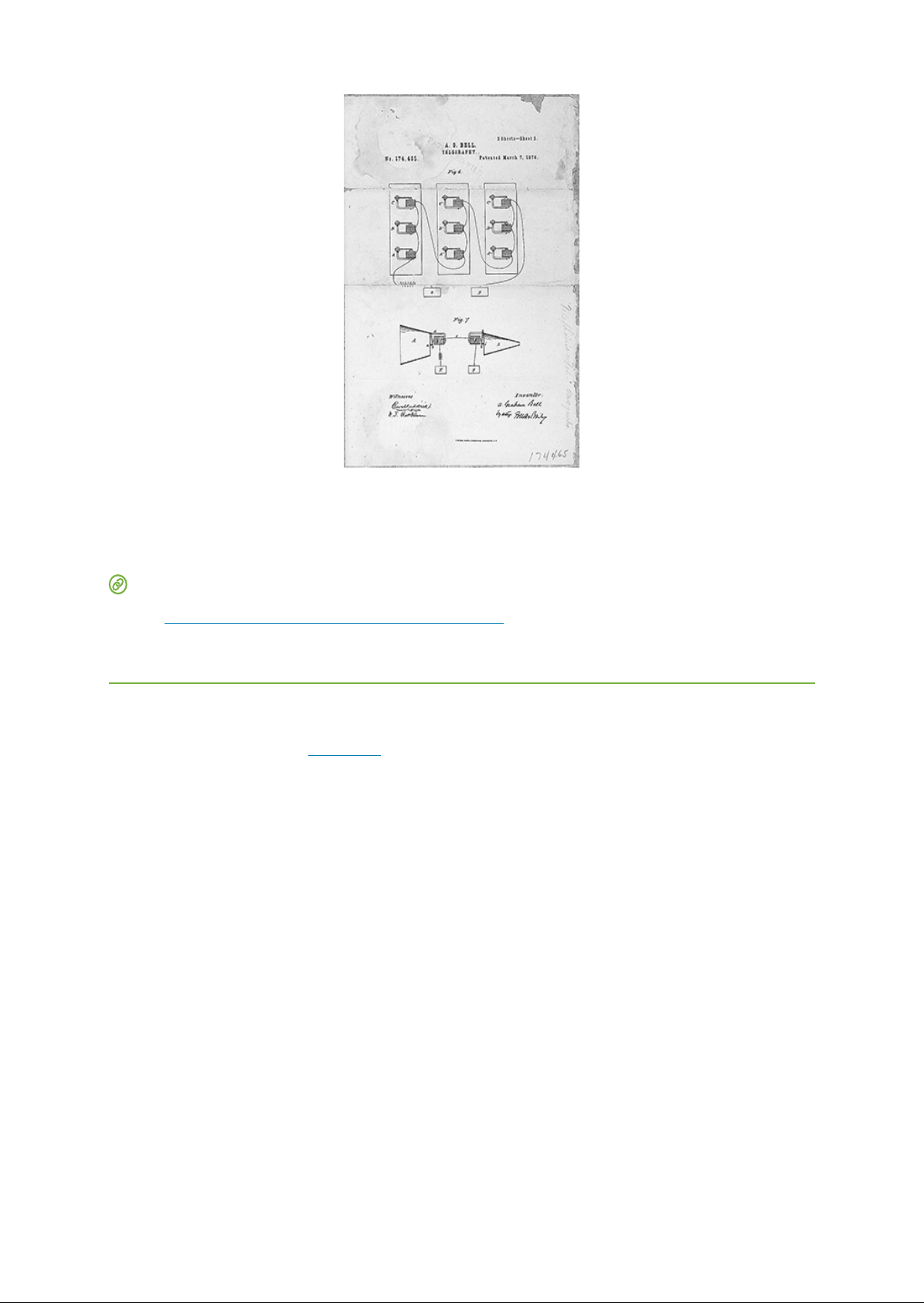

466 18 and the Rise of Big Business , groundwork for the modern women movement . Women who had the means to purchase such items could use their time to seek other employment outside of the home , as well as broaden their knowledge through education and reading . Such a transformation did not occur overnight , as these inventions also increased expectations for women to remain tied to the home and their domestic chores slowly , the culture of domesticity changed . Perhaps the most important industrial advancement of the era came in the production of steel . Manufacturers and builders preferred steel to iron , clue to its increased strength and durability . After the Civil War , two new processes allowed for the creation of furnaces large enough and hot enough to melt the wrought iron needed to produce large quantities of steel at increasingly cheaper prices . The Bessemer process , named for English inventor Henry Bessemer , and the process , changed the way the United States produced steel and , in doing so , led the country into a new industrialized age . As the new material became more available , builders eagerly sought it out , a demand that steel mill owners were happy to supply . In 1860 , the country produced thirteen thousand tons of steel . By 1879 , American furnaces were producing over one million tons per year by 1900 , this had risen to ten million . Just ten years later , the United States was the top steel producer in the world , at over million tons annually . As production increased to match the overwhelming demand , the price of steel dropped by over 80 percent . When quality steel became cheaper and more readily available , other industries relied upon it more heavily as a key to their growth and development , including construction and , later , the automotive industry . As a result , the steel industry rapidly became the cornerstone of the American economy , remaining the primary indicator of industrial growth and stability through the end of World War II . ALEXANDER GRAHAM BELL AND THE TELEPHONE Advancements in communications matched the pace of growth seen in industry and home life . Communication technologies were changing quickly , and they brought with them new ways for information to travel . In 1858 , British and American crews laid the transatlantic cable lines , ing messages to pass between the United States and Europe in a matter of hours , rather than waiting the few weeks it could take for a letter to arrive by steamship . Although these initial cables worked for barely a month , generated great interest in developing a more telecommunications industry . Within twenty years , over miles of cable crisscrossed the ocean floors , connecting all the continents . Domestically , Wes ern Union , which controlled 80 percent of the country telegraph lines , operated nearly miles te routes from coast to coast . In short , people were connected like never before , able to relay messages in minutes and hours rather than days and weeks . One of the greatest advancements was the telephone , which Alexander Graham Bell pa en ed in 1876 Figure ) While he was not the to invent the concept , Bell was the one to capitalize on it after securing the patent , he worked with and businessmen to create the National Bell Tele Company . Western Union , which had originally turned down Bell machine , went on to commission ' invent an improved version of the telephone . It is actually Edison version that is most ike the modern telephone used today . However , Western Union , fearing a costly legal battle they were li ely to lose due to patent , ultimately sold Edison idea to the Bell Company . With the communications inc now largely in their control , along with an agreement from the federal government to permit such con ro , the Bell Company was transformed into the American Telephone and Telegraph Company , which still oday as AT . By 1880 , thousand telephones were in use in the United States , including one at the House . By 1900 , that number had increased to million , and hundreds of American cities had obtained local service for their citizens . Quickly and inexorably , technology was bringing the country into closer con act , changing forever the rural isolation that had America since its beginnings . Edison to Access for free at .

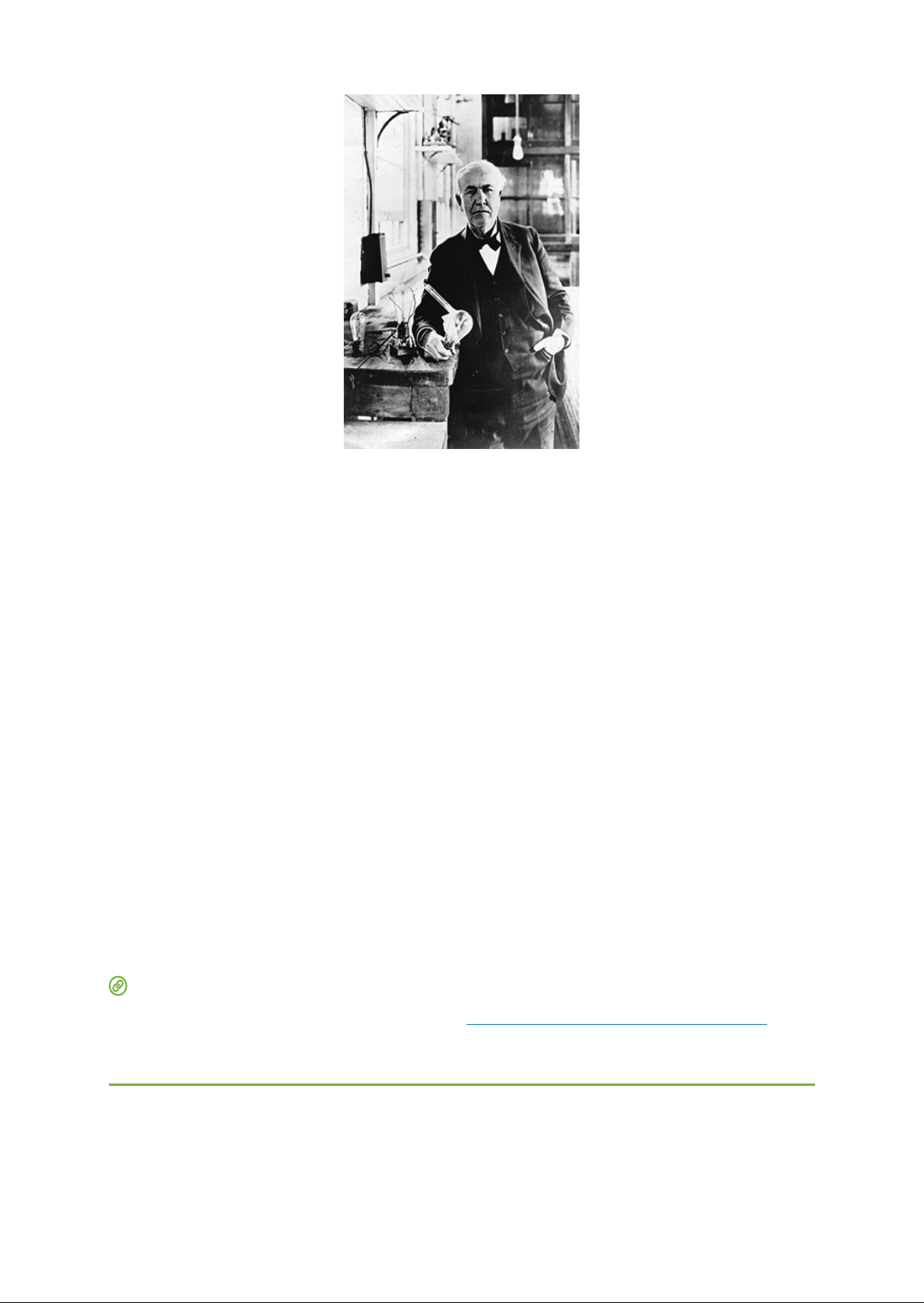

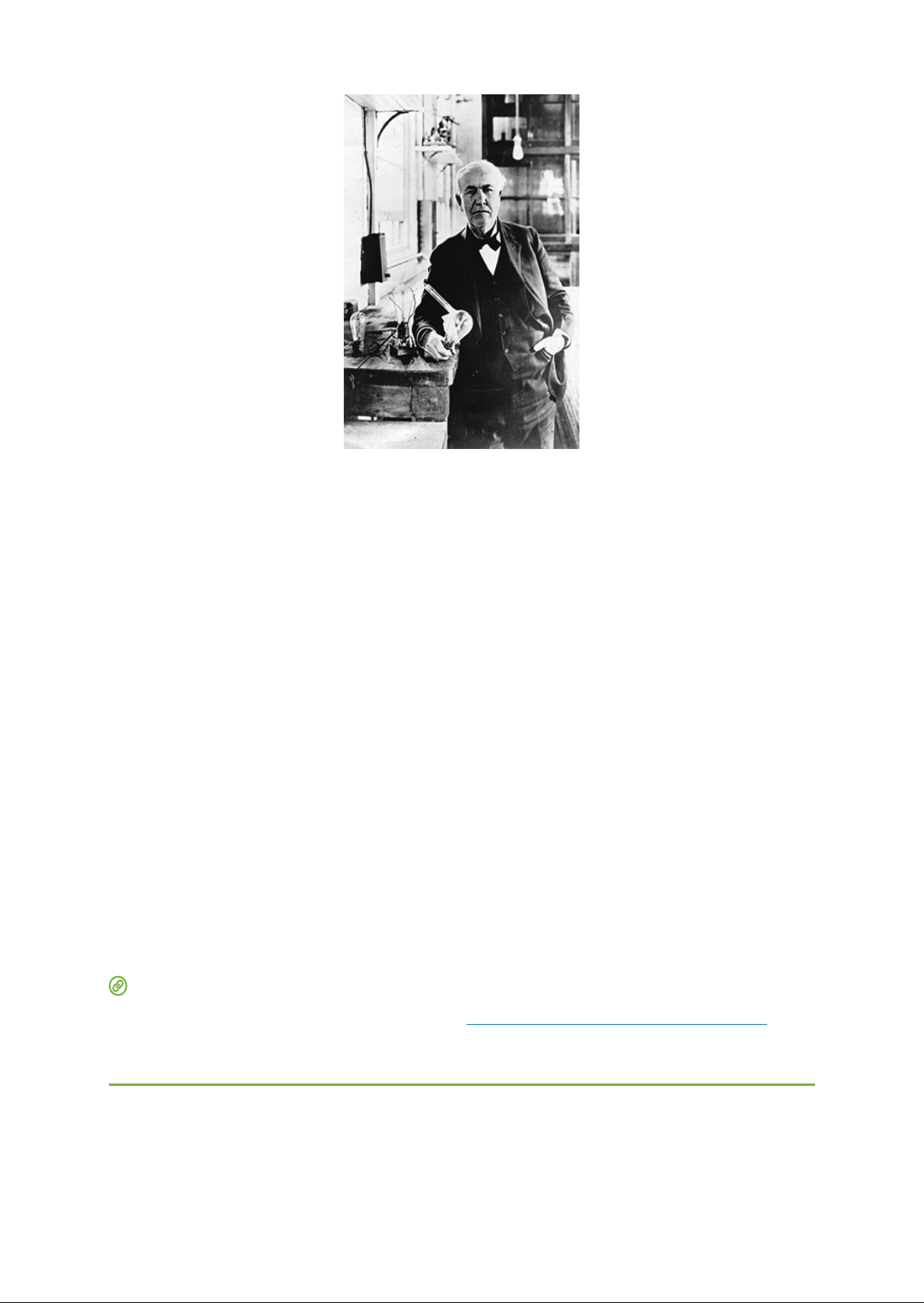

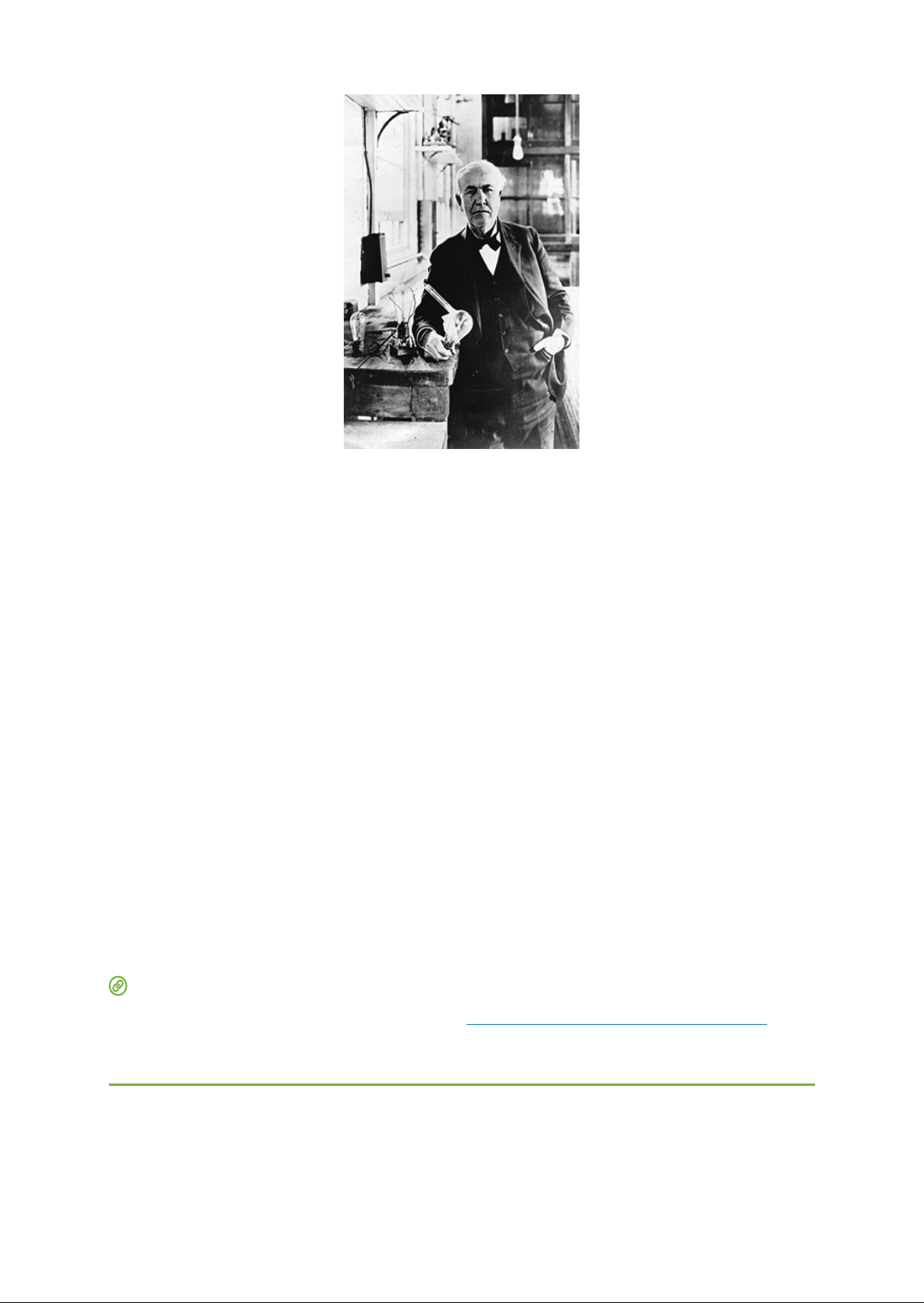

Inventors of the Age 467 A a nu . FIGURE Alexander Graham Bell patent of the telephone was one of almost patents issued between 1850 and 1900 . Although the patent itself was only six pages long , pages of illustrations , it proved to be one of the most contested and of the nineteenth century . credit Us . National Archives and Records Administration ) CLICK AND EXPLORE Visit the Library of Congress ( telephone ) to examine the controversy over the invention of the telephone . While Alexander Graham Bell is credited with the invention , several other inventors played a role in its development however , Bell was the to patent the device . THOMAS EDISON AND ELECTRIC LIGHTING Although Thomas Alva Edison ( Figure ) is best known for his contributions to the electrical industry , his experimentation went far beyond the light bulb . Edison was quite possibly the greatest inventor of the turn of the century , saying famously that he hoped to have a minor invention every ten days and a big thing every month or He registered patents over his lifetime and ran a laboratory , Menlo Park , which housed a rotating group of up to scientists from around the globe . Edison became interested in the telegraph industry as a boy , when he worked aboard trains selling candy and newspapers . He soon began tinkering with telegraph technology and , by 1876 , had devoted himself full time to lab work as an inventor . He then proceeded to invent a string of items that are still used today the phonograph , the mimeograph machine , the motion picture projector , the dictaphone , and the storage battery , all using a assembly line process that made the rapid production of inventions possible .

468 18 and the Rise of Big Business , FIGURE Thomas Alva Edison was the quintessential inventor of the era , with a passion for new ideas and over one thousand patents to his name . Seen here with his incandescent light bulb , which he invented in 1879 , Edison produced many inventions that subsequently transformed the country and the world , In 1879 , Edison invented the item that has led to his greatest fame the practical incandescent light bulb . He allegedly explored over six thousand different materials for the , before stumbling upon carbonized cotton thread as the ideal substance . By 1882 , with backing largely from Morgan , he had created the Edison Electric Illuminating Company , which began supplying electrical current to a small number of customers in New York City . Morgan guided subsequent mergers of Edison other enterprises , including a machine works and a lamp company , resulting in the creation of the Edison General Electric Company in 1889 . The next stage of invention in electric power came about with the contribution of George . was responsible for making electric lighting possible on a national scale . While Edison used direct current or power , which could only extend two miles from the power source , in 1886 , founded an electric company that promoted alternating current or AC power , which allowed for delivery over greater distances due to its wavelike patterns . The Electric Company delivered AC power , which meant that factories , homes , and short , anything that needed be served , regardless of their proximity to the power source . A public relations battle ensued between the and Edison camps , coinciding with the invention of the electric chair as a form of prisoner execution . Edison publicly proclaimed AC power to be best adapted for use in the chair , in the hope that such a smear campaign would result in homeowners becoming reluctant to use AC power in their houses . Although Edison originally fought the use of AC power in other devices , he reluctantly adapted to it as its popularity increased . CLICK AND EXPLORE Not all of Edison ventures were successful . Read about Edison ( to learn the story behind his greatest failure . Was there some to his efforts ?

Or was it wasted time and money ?

Access for free at .

From Invention to Industrial Growth 469 From Invention to Industrial Growth LEARNING OBJECTIVES By the end ofthis section , you will be able to Explain how the inventions ofthe late nineteenth century contributed directly to industrial growth in America contributions of Andrew Carnegie , John Rockefeller , and Morgan to the new industrial order emerging in the late nineteenth century Describe the visions , philosophies , and business methods ofthe leaders ofthe new industrial order As discussed previously , new processes in steel , along with inventions in the of communications and electricity , transformed the business landscape of the nineteenth century . The exploitation of these new provided opportunities for tremendous growth , and business entrepreneurs with and the right mix of business acumen and ambition could make their fortunes . Some of these new millionaires were known in their day as robber barons , a negative term that the belief that they exploited workers and bent laws to succeed . Regardless of how they were perceived , these businessmen and he companies they created revolutionized American industry . RAILROADS AND ROBBER BARONS Earlier in the nineteenth century , the transcontinental railroad and subsequent spur lines paved the way or rapid and explosive railway growth , as well as stimulated growth in the iron , wood , coal , and other related industries . The railroad industry quickly became the nations big A powerful , inexpensive , and consistent form of transportation , railroads accelerated the development of virtually every other industry in he country . By 1890 , railroad lines covered nearly every corner of the United States , bringing raw materials to industrial factories and goods to consumer markets . The amount of track grew from miles at he end of the Civil War to over miles by the close of the century . Inventions such as car couplers , air , and Pullman passenger cars allowed the volume of both freight and people to increase steadily . From 877 to 1890 , both the amount of goods and the number traveling the rails tripled . Financing for all of this growth came through a combination of private capital and government loans and grants . Federal and state loans of cash and land grants totaled 150 million and 185 million acres of public land , respectively . Railroads also listed their stocks and bonds on the New York Stock Exchange to attract investors from both within the United States and Europe . Individual investors consolidated their power as railroads merged and companies grew in size and power . These individuals became some of the wealthiest Americans the country had ever known . Midwest farmers , angry at large railroad owners for their exploitative business practices , came to refer to them as robber barons , as their business dealings were frequently shady and exploitative . Among their highly questionable tactics was the practice of differential shipping rates , in which larger business enterprises received discounted rates to transport their goods , as opposed to local producers and farmers whose higher rates essentially subsidized the discounts . Jay Gould was perhaps the prominent railroad magnate to be tarred with the robber baron brush . He bought older , smaller , rundown railroads , offered minimal improvements , and then capitalized on factory owners desires to ship their goods on this increasingly popular and more form of transportation . His work with the Erie Railroad was notorious among other investors , as he drove the company to near ruin in a failed attempt to attract foreign investors during a takeover attempt . model worked better in the American West , where the railroads were still widely scattered across the country , forcing farmers and businesses to pay whatever prices Gould demanded in order to use his trains . In addition to owning the Union Railroad that helped to construct the original transcontinental railroad line , Gould came to control over ten thousand miles of track across the United States , accounting for 15 percent of all railroad transportation . When he died in 1892 , Gould had a personal worth of over 100 million , although he was a deeply unpopular . In contrast to Gould exploitative business model , which focused on more than on tangible

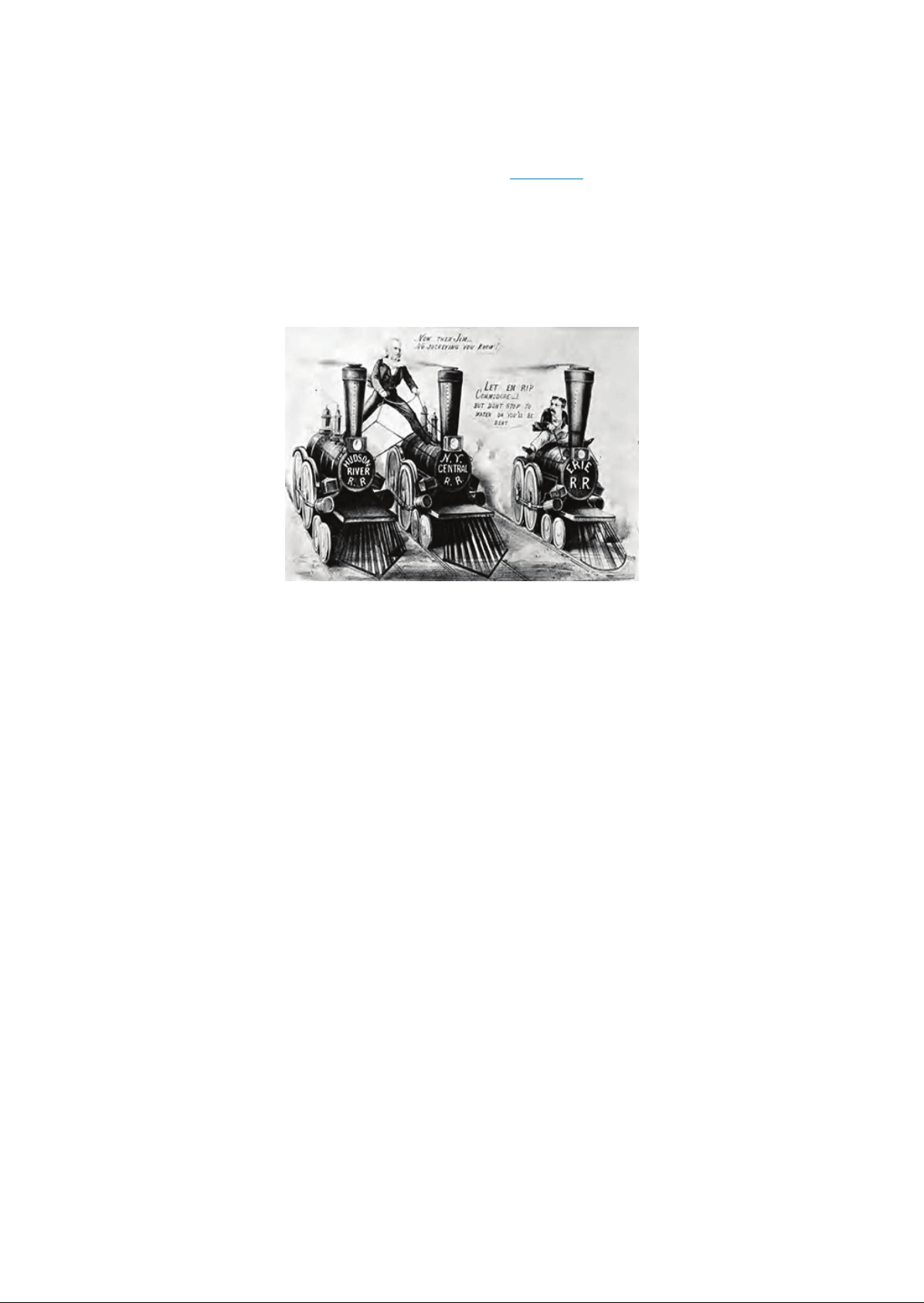

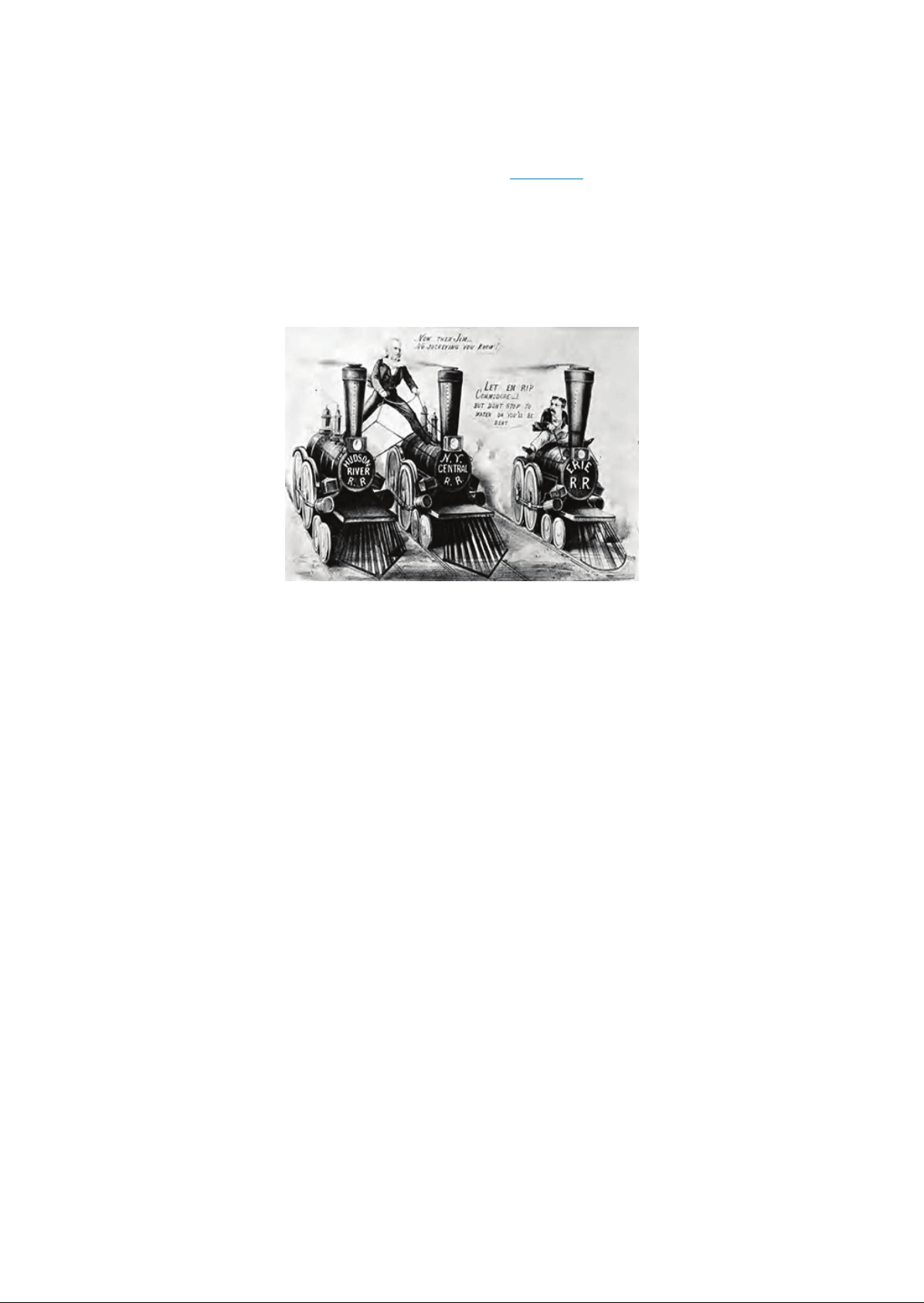

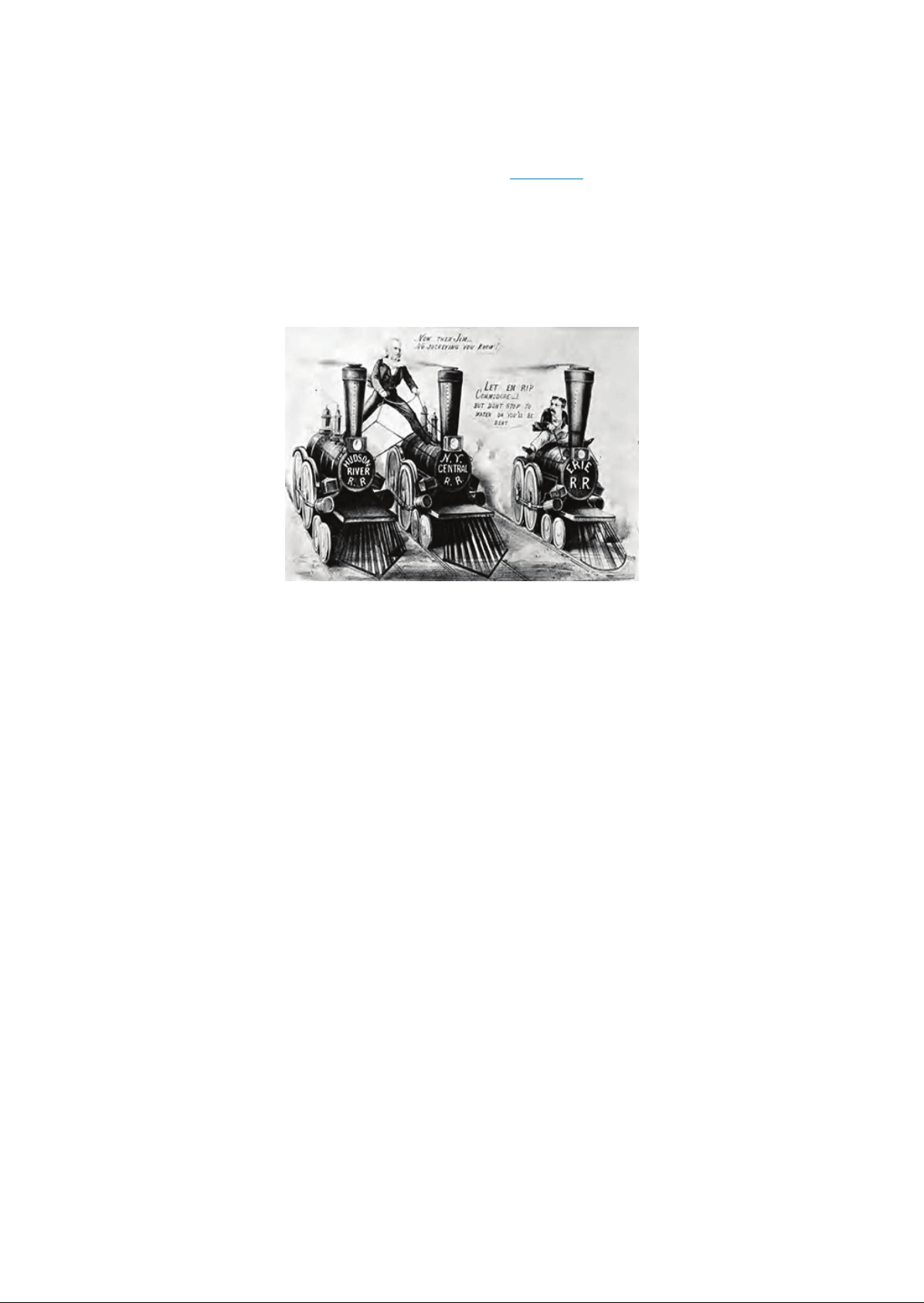

470 18 and the Rise of Big Business , industrial contributions , Commodore Cornelius Vanderbilt was a robber baron who truly cared about the success of his railroad enterprise and its positive impact on the American economy . Vanderbilt consolidated several smaller railroad lines , called trunk lines , to create the powerful New York Central Railroad Company , one of the largest corporations in the United States at the time Figure . He later purchased stock in the major rail lines that would connect his company to Chicago , thus expanding his reach and power while simultaneously creating a railroad network to connect Chicago to New York City . This consolidation provided more connections from Midwestern suppliers to eastern markets . It was through such consolidation that , by 1900 , seven major railroad tycoons controlled over 70 percent of all operating lines . personal wealth at his death ( over 100 million in 1877 ) placed him among the top three wealthiest individuals in American history . FIGURE The Great Race for the Western Stakes , a Currier Ives lithograph from 1870 , depicts one of Cornelius Vanderbilt rare failed attempts at further consolidating his railroad empire , when he lost his battle with James Fisk , Jay Gould , and Daniel Drew for control of the Erie Railway Company , GIANTS OF WEALTH CARNEGIE , ROCKEFELLER , AND MORGAN The War inventors generated ideas that transformed the economy , but they were not big businessmen . The evolution from technical innovation to massive industry took place at the hands of the entrepreneurs whose business gambles paid off , making them some of the richest Americans of their day . Steel magnate Andrew Carnegie , oil tycoon John Rockefeller , and business Morgan were all businessmen who grew their respective businesses to a scale and scope that were unprecedented . Their companies changed how Americans lived and worked , and they themselves greatly the growth of the country . Andrew Carnegie and The Gospel of Wealth Andrew Carnegie , steel magnate , has the prototypical story . Although such stories resembled more myth than reality , they served to encourage many Americans to seek similar paths to fame and fortune . In Carnegie , the story was one of few derived from fact . Born in Scotland , Carnegie immigrated with his family to Pennsylvania in 1848 . Following a brief stint as a bobbin boy , changing spools of thread at a Pittsburgh clothing manufacturer at age thirteen , he subsequently became a telegram messenger boy . As a messenger , he spent much of his time around the Pennsylvania Railroad and developed parallel interests in railroads , bridge building , and , eventually , the steel industry . himself to his supervisor and future president of the Pennsylvania Railroad , Tom Scott , Carnegie worked his way into a position of management for the company and subsequently began to invest some of his earnings , with Scott guidance . One particular investment , in the booming oil of northwest Pennsylvania in 1864 , resulted in Carnegie earning over million in cash dividends , thus providing him with the capital necessary to pursue his ambition to modernize the iron and steel industries , transforming the United States in the process . Having seen during the Civil War , when he served as Superintendent of Military Railways Access for free at .

From Invention to Industrial Growth 471 and telegraph coordinator for the Union forces , the importance of industry , particularly steel , to the future growth of the country , Carnegie was convinced of his strategy . His company was the Edgar Thompson Steel Works , and , a decade later , he bought out the newly built Homestead Steel Works from the Pittsburgh Bessemer Steel Company . By the end of the century , his enterprise was running an annual in excess of 40 million ( Figure . an . FIGURE Andrew Carnegie made his fortune in steel at such factories as the Carnegie Steel Works located in Youngstown , Ohio , where new technologies allowed the strong metal to be used in far more applications than ever before . Carnegie empire grew to include iron ore mines , furnaces , mills , and steel works companies . Although not a expert in steel , Carnegie was an excellent promoter and salesman , able to locate backing for his enterprise . He was also shrewd in his calculations on consolidation and expansion , and was able to capitalize on smart business decisions . Always thrifty with the he earned , a trait owed to his upbringing , Carnegie saved his during prosperous times and used them to buy out other steel companies at low prices during the economic recessions of the and . He insisted on machinery and equipment , and urged the men who worked at and managed his steel mills to constantly think of innovative ways to increase production and reduce cost . Carnegie , more than any other businessman of the era , championed the idea that America leading tycoons owed a debt to society . He believed that , given the circumstances of their successes , they should serve as benefactors to the less fortunate public . For Carnegie , poverty was not an abstract concept , as his family had been a part of the struggling masses . He desired to set an example of philanthropy for all other prominent industrialists of the era to follow . Carnegie famous essay , The Gospel of Wealth , featured below , expounded on his beliefs . In it , he borrowed from Herbert Spencer theory of social Darwinism , which held that society developed much like plant or animal life through a process of evolution in which the most and capable enjoyed the greatest material and social success . MY STORY Andrew Carnegie on Wealth Carnegie applauded American capitalism for creating a society where , through hard work , ingenuity , and a bit of luck , someone like himself could amass a fortune . In return for that opportunity , Carnegie wrote that the wealthy should proper uses for their wealth by funding hospitals , libraries , colleges , the arts , and more . The Gospel of Wealth spelled out that responsibility . Poor and restricted are our opportunities in this life narrow our horizon our best work most imperfect but rich men should be thankful for one inestimable boon . They have it in their power lives to busy themselves in organizing from which the masses of their fellows will derive lasting advantage , and thus dignify their own lives . This , then , is held to be the duty of the man of Wealth First , to set an example of modest , unostentatious living ,

472 18 Industrialization and the Rise of Big Business , shunning display or extravagance to provide moderately for the legitimate wants of those dependent upon him and after doing so to consider all surplus revenues which come to him simply as trust funds , which he is called upon to administer , and strictly bound as a matter of duty to administer in the manner which , in his judgment , is best calculated to produce the most results for the man of wealth thus becoming the mere agent and trustee for his poorer brethren , bringing to their service his superior wisdom , experience and ability to administer , betterthan they would or could do for themselves . In bestowing charity , the main consideration should be to help those who will help themselves to provide part of the means by which those who desire to improve may do so to give those who desire to use the aids by which they may rise to assist , but rarely or never to do all . Neither the individual nor the race is improved by giving . Those worthy of assistance , except in rare cases , seldom require assistance . The really valuable men of the race never do , except in cases of accident or sudden change . Every one has , of course , cases of individuals brought to his own knowledge where temporary assistance can do genuine good , and these he will not overlook . But the amount which can be wisely given by the individual for individuals is necessarily limited by his lack of knowledge of the circumstances connected with each . He is the only true reformer who is as careful and as anxious not to aid the unworthy as he is to aid the worthy , and , perhaps , even more so , for in more injury is probably done by rewarding vice than by relieving virtue . Carnegie , The Gospel of Wealth Social Darwinism added a layer of pseudoscience to the idea of the man , a desirable thought for all who sought to follow Carnegie example . The myth of the businessman was a potent one . Author Horatio Alger made his own fortune writing stories about young enterprising boys who beat poverty and succeeded in business through a combination of luck and pluck . His stories were immensely popular , even leading to a board game Figure ) where players could hope to win in the same way that his heroes did . FIGURE Based on a book by Horatio Alger , District Messenger Boy was a board game where players could Access for free at .

From Invention to Industrial Growth 473 achieve the ultimate goal of material success . Alger wrote hundreds of books on a common theme A poor but hardworking boy can get ahead and make his fortune through a combination of luck and . John Rockefeller and Business Integration Models Like Carnegie , John Rockefeller was born in 1839 of modest means , with a ly absent traveling salesman of a father who sold medicinal elixirs and other wares . Young Rockefeller helped his mother with various chores and earned extra money for the family through the sale of family farm . When the family moved to a suburb of Cleveland in 1853 , he had an opportunity to take ing and bookkeeping courses while in high school and developed a career interest in business . While living in in 1859 , he learned of Colonel Edwin Drake who had struck black gold , or oil , near , Pennsylvania , setting off a boom even greater than the California Gold Rush of the previous decade . Many sough to a fortune through risky and chaotic wildcatting , or drilling exploratory oil wells , hoping to strike it rich . Bu Rockefeller chose a more certain investment crude oil into kerosene , which could be used for both heating and lamps . As a more source of energy , as well as less dangerous to produce , kerosene quickly replaced whale oil in many businesses and homes . Rockefeller worked initially with family and friends in tie re business located in the Cleveland area , but by 1870 , Rockefeller ventured out on his own , ing his resources and creating the Standard Oil Company of Ohio , initially valued at million . Rockefeller was ruthless in his pursuit of total control of the oil business . As other entrepreneurs the area seeking a quick fortune , Rockefeller developed a plan to crush his and create a true monopoly in the industry . Beginning in 1872 , he forged agreements with several large railroad companies to obtain discounted freight rates for shipping his product . He also used the railroad companies to gather information on his competitors . As he could now deliver his kerosene at lower prices , he drove his competition out of business , often offering to buy them out for pennies on the dollar . He hounded those who refused to sell out to him , until they were driven out of business . Through his method of growth via mergers and acquisitions of similar as horizontal integration Oil grew to include almost all in the area . By 1879 , the Standard Oil Company controlled nearly 95 percent of all oil businesses in the country , as well as 90 percent of all the businesses in the world . Editors of the New York World lamented of Standard Oil in 1880 that , When the nineteenth century shall have passed into history , the impartial eyes of the reviewers will be amazed to that the . tolerated the presence of the most gigantic , the most cruel , impudent , pitiless and grasping monopoly that ever fastened itself upon a country . Seeking still more control , Rockefeller recognized the advantages of controlling the transportation of his product . He next began to grow his company through vertical integration , wherein a company handles all aspects of a product lifecycle , from the creation of raw materials through the production process to the delivery of the product . In Rockefeller case , this model required investment and acquisition of companies involved in everything from to pipelines , tanker cars to railroads . He came to own almost every type of business and used his vast power to drive competitors from the market through intense price wars . Although by competitors who suffered from his takeovers and considered him to be no better than a robber baron , several observers lauded Rockefeller for his ingenuity in integrating the oil industry and , as a result , lowering kerosene prices by as much as 80 percent by the end of the century . Other industrialists quickly followed suit , including Swift , who used vertical integration to dominate the meatpacking industry in the late nineteenth century . In order to control the variety of interests he now maintained in industry , Rockefeller created a new legal entity , known as a trust . In this arrangement , a small group of trustees possess legal ownership of a business that they operate for the of other investors . In 1882 , all stockholders in the various Standard Oil enterprises gave their stock to nine trustees who were to control and direct all of the business ventures . State and federal challenges arose , due to the obvious appearance of a monopoly , which implied sole ownership of all enterprises composing an entire industry . When the Ohio Supreme Court ruled

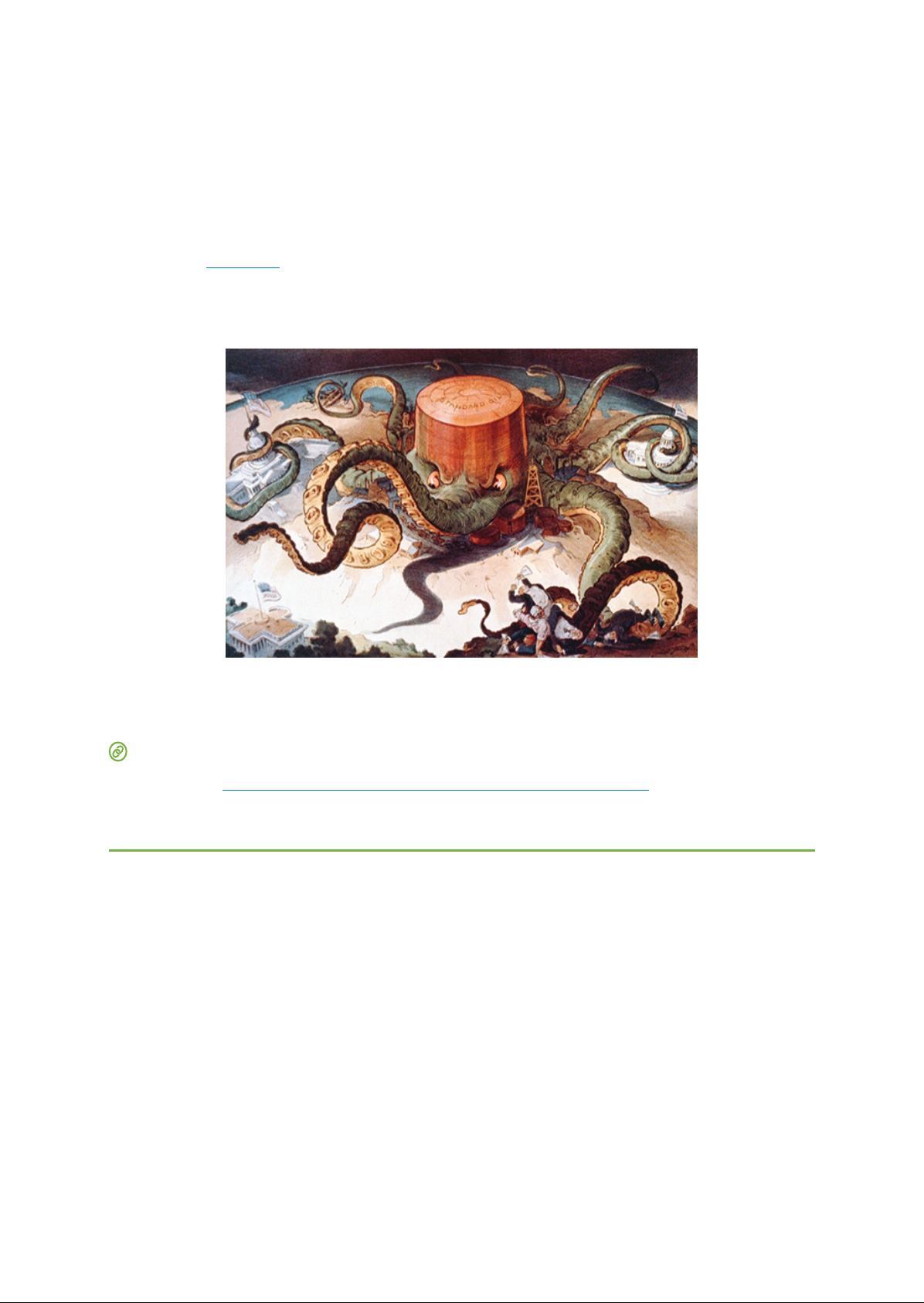

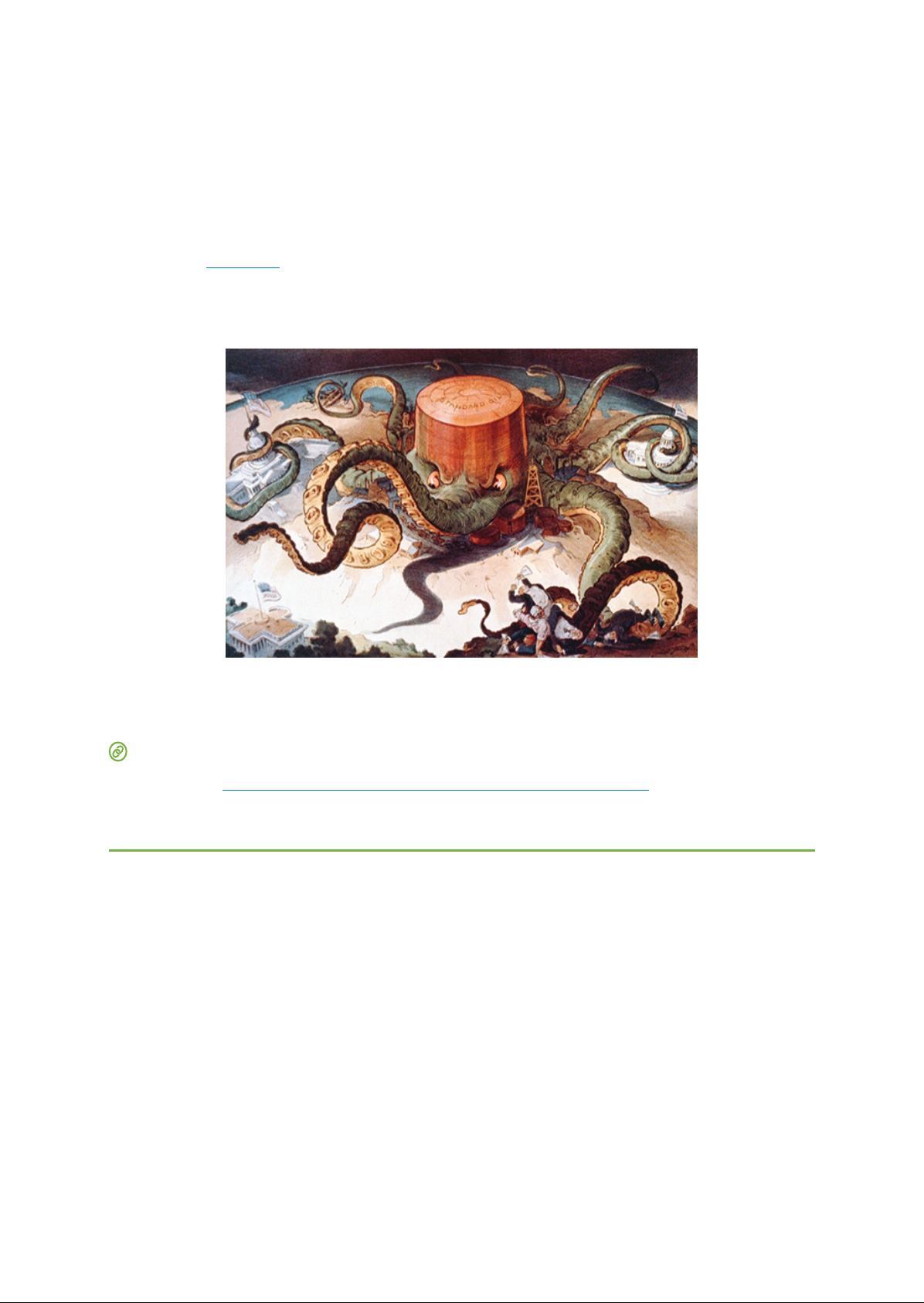

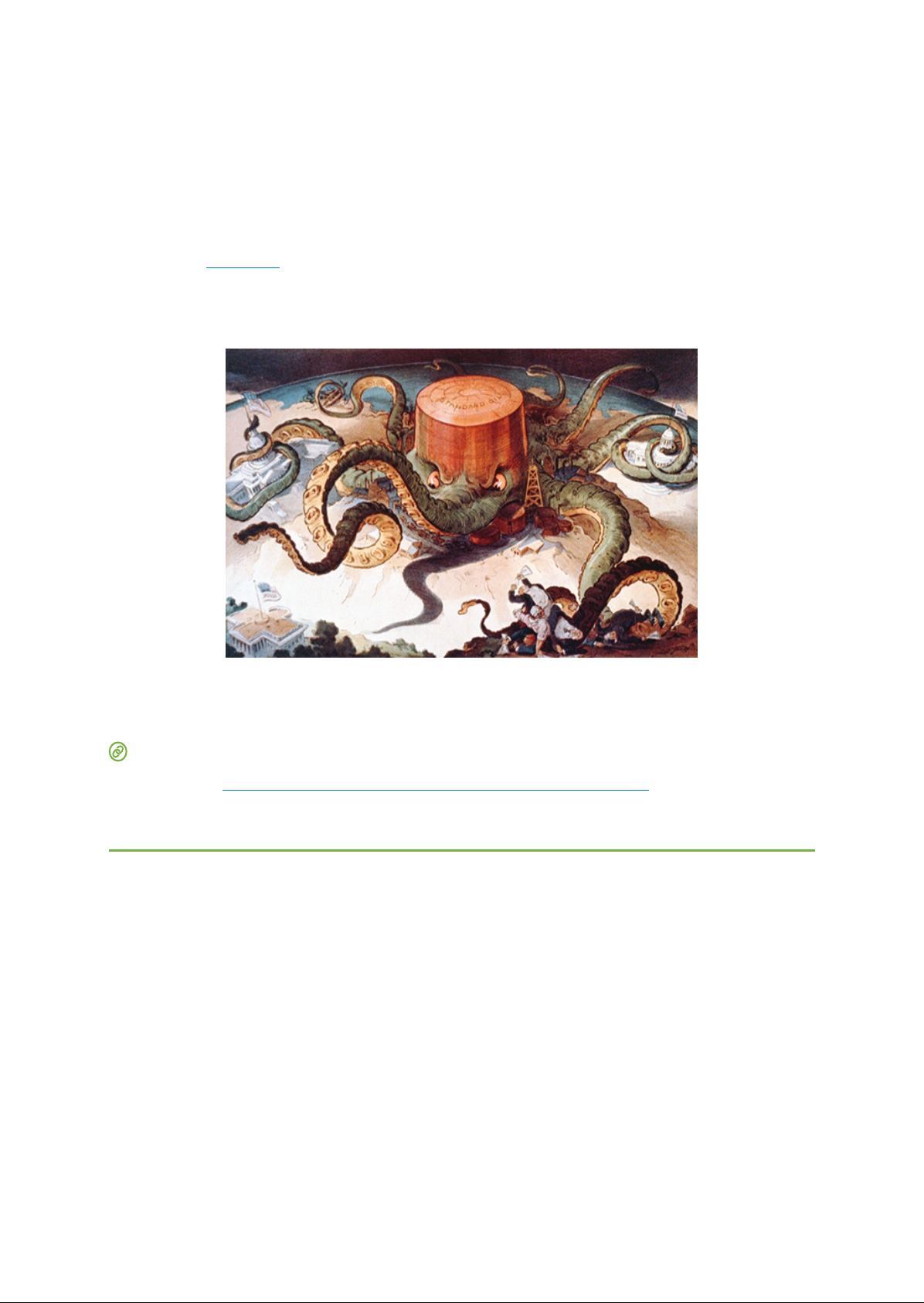

474 18 and the Rise of Big Business , that the Standard Oil Company must dissolve , as its monopoly control over all operations in the was in violation of state and federal statutes , Rockefeller shifted to yet another legal entity , called a holding company model . The holding company model created a central corporate entity that controlled the operations of multiple companies by holding the majority of stock for each enterprise . While not technically a trust and therefore not vulnerable to laws , this consolidation of power and wealth into one entity was on par with a monopoly thus , progressive reformers of the late nineteenth century considered holding companies to epitomize the dangers inherent in capitalistic big business , as can be seen in the political cartoon below Figure . to reformers misgivings , other businessmen followed Rockefeller example . By 1905 , over three hundred business mergers had occurred in the United States , affecting more than 80 percent of all industries . By that time , despite passage of federal legislation such as the Sherman Trust Act in 1890 , percent of the country businesses controlled over 40 percent of the nation economy . FIGURE John Rockefeller , like Carnegie , grew from modest means to a vast fortune . Unlike Carnegie , however , his business practices were often predatory and aggressive . This cartoon from the era shows how his conglomerate , Standard Oil , was perceived by progressive reformers and other critics . CLICK AND EXPLORE The video on Robber Barons or Industrial Giants ( presents a lively discussion of whether the industrialists of the nineteenth century were really robber barons or if they were industrial giants . Pierpont Morgan Unlike Carnegie and Rockefeller , Morgan was no hero . He was born to wealth and became much wealthier as an investment banker , making wise decisions in support of the entrepreneurs building their fortunes . Morgan father was a London banker , and Morgan the son moved to New York in 1857 to look after the family business interests there . Once in America , he separated from the London bank and created the Pierpont Morgan and Company . The bought and sold stock in growing companies , investing the family wealth in those that showed great promise , turning an enormous as a result . Investments from such as his were the key to the success stories of businessmen like Carnegie and Rockefeller . In return for his investment , Morgan and other investment bankers demanded seats on the companies boards , which gave them even greater control over policies and decisions than just investment alone . There were many critics of Morgan and these other bankers , particularly among members of a congressional subcommittee who investigated the control that maintained over key industries in the country . The subcommittee referred to Morgan enterprise as a form of money trust that was even more powerful than the trusts operated by Rockefeller and others . Morgan argued Access for free at .

Building Industrial America on the Backs of Labor 475 hat his , and others like it , brought stability and organization to a capitalist economy , and likened his role to a kind of public service . Ultimately , Morgan most notable investment , and greatest consolidation , was in the steel industry , when he out Andrew Carnegie in 1901 . Initially , Carnegie was reluctant to sell , but after repeated badgering by Morgan , Carnegie named his price an outrageously sum of 500 million . Morgan agreed without , and then consolidated Carnegie holdings with several smaller steel to create the Steel Corporation . Steel was subsequently capitalized at billion . It was the country . Lauded by admirers for the and modernization he brought to investment banking practices , as well as for his philanthropy and support of the arts , Morgan was also criticized by reformers who subsequently his ( and other bankers ) efforts for contributing to the bubble of prosperity that eventually ) St in the Great Depression of the . What none could doubt was that Morgan aptitude and savvy business dealings kept him in good stead . A subsequent congressional committee , in 1912 , reported hat his held 341 directorships in 112 corporations that controlled over 22 billion in assets . In comparison , that amount of wealth was greater than the assessed value of all the land in the United States west of the Mississippi River . Building Industrial America on the Backs of Labor LEARNING OBJECTIVES By the end ofthis section , you will be able to Explain the qualities of industrial life in the late nineteenth century Analyze both workers desire for labor unions and the reasons for unions inability to achieve their goals The growth of the American economy in the last half of the nineteenth century presented a paradox . The standard of living for many American workers increased . As Carnegie said in The Gospel of Wealth , the poor enjoy what the rich could not before afford . What were the luxuries have become the necessaries of life . The laborer has now more comforts than the landlord had a few generations ago . In many ways , Carnegie was correct . The decline in prices and the cost of living meant that the industrial era offered many Americans relatively better lives in 1900 than they had only decades before . For some Americans , there were also increased opportunities for upward mobility . For the multitudes in the working class , however , conditions in the factories and at home remained deplorable . The they faced led many workers to question an industrial order in which a handful of wealthy Americans built their fortunes on the backs of workers . LIFE Between the end of the Civil War and the turn of the century , the American workforce underwent a transformative shift . In 1865 , nearly 60 percent of Americans still lived and worked on farms by the early , that number had reversed itself , and only 40 percent still lived in rural areas , with the remainder living and working in urban and early suburban areas . A number of these urban and suburban dwellers earned their wages in factories . Advances in farm machinery allowed for greater production with less manual labor , thus leading many Americans to seek job opportunities in the burgeoning factories in the cities . Not surprisingly , there was a concurrent trend of a decrease in American workers being and an increase of those working for others and being dependent on a factory wage system for their living . Yet factory wages were , for the most part , very low . In 1900 , the average factory wage was approximately twenty cents per hour , for an annual salary of barely six hundred dollars . According to some historical estimates , that wage left approximately 20 percent of the population in industrialized cities at , or below , the poverty level . An average factory work week was sixty hours , ten hours per day , six days per week , although in steel mills , the workers put in twelve hours per day , seven days a week . Factory owners had little concern for workers safety . According to one of the few available accurate measures , as late as 1913 , nearly Americans lost their lives on the job , while another workers suffered from injuries that resulted in at least one missed month of work . Another element of hardship for workers was the increasingly dehumanizing

476 18 and the Rise of Big Business , nature of their work . Factory workers executed repetitive tasks throughout the long hours of their shifts , seldom interacting with coworkers or supervisors . This solitary and repetitive work style was a adjustment for those used to more collaborative and work , whether on farms or in crafts shops . Managers embraced Fredrick Taylor principles of management , also called management , where he used studies to divide manufacturing tasks into short , repetitive segments . A mechanical engineer by training , Taylor encouraged factory owners to seek and over any of personal interaction . Owners adopted this model , effectively making workers cogs in a machine . One result of the new breakdown of work processes was that factory owners were able to hire women and children to perform many of the tasks . From 1870 through 1900 , the number of women working outside the home tripled . By the end of this period , million American women were wage earners , with of them working factory jobs . Most were young , under , and either immigrants themselves or the daughters of immigrants . Their foray into the working world was not seen as a step towards empowerment or equality , but rather a hardship born of necessity . Women factory work tended to be in clothing or textile factories , where their appearance was less offensive to men who felt that heavy industry was their purview . Other women in the workforce worked in clerical positions as bookkeepers and secretaries , and as . Not surprisingly , women were paid less than men , under the pretense that they should be under the care of a man and did not require a living wage . Factory owners used the same rationale for the exceedingly low wages they paid to children . Children were small enough to easily among the machines and could be hired for simple work for a fraction of an adult man pay . The image below ( Figure shows children working the night shift in a glass factory . From 1870 through 1900 , child labor in factories tripled . Growing concerns among progressive reformers over the safety of women and children in the workplace would eventually result in the development of political lobby groups . Several states passed legislative efforts to ensure a safe workplace , and the lobby groups pressured Congress to pass protective legislation . However , such legislation would not be forthcoming until well into the twentieth century . In the meantime , many immigrants still desired the additional wages that child and women labor produced , regardless of the harsh working conditions . FIGURE A photographer took this image of children working in a New York glass factory at midnight . There , as in countless other factories around the country , children worked around the clock in and dangerous conditions . Access for free at .

Building Industrial America on the Backs of Labor 477 WORKER PROTESTS AND VIOLENCE Workers were well aware of the vast discrepancy between their lives and the wealth of the factory owners . Lacking the assets and legal protection needed to organize , and deeply frustrated , some working communities erupted in spontaneous violence . The coal mines of eastern Pennsylvania and the railroad yards of western Pennsylvania , central to both respective industries and home to large , immigrant , working enclaves , saw the brunt of these outbursts . The combination of violence , along with several other factors , blunted any efforts to organize workers until well into the twentieth century . Business owners viewed organization efforts with great mistrust , capitalizing upon widespread sentiment among the general public to crush unions through open shops , the use of , contracts ( in which the employee agrees to not join a union as a of employment ) and other means . Workers also faced obstacles to organization associated with race and ethnicity , as questions arose on how to address the increasing number of African American workers , in addition to the language and cultural barriers introduced by the large wave of southeastern European immigration to the United States . But in large part , the greatest obstacle to effective unionization was the general public continued belief in a strong work ethic and that an individual work organizing into radical reap its own rewards . As violence erupted , such events seemed only to widespread popular sentiment that radical , elements were behind all union efforts . In the , Irish coal miners in eastern Pennsylvania formed a secret organization known as the Molly Maguires , named for the famous Irish patriot . Through a series of scare tactics that included kidnappings , and even murder , the Molly Maguires sought to bring attention to the miners plight , as well as to cause enough damage and concern to the mine owners that the owners would pay attention to their concerns . Owners paid attention , but not in the way that the protesters had hoped . They hired detectives to pose as miners and mingle among the workers to obtain the names of the Molly Maguires . By 1875 , they had acquired he names of suspected Maguires , who were subsequently convicted of murder and violence against property . All were convicted and ten were hanged in 1876 , at a public Day of the Rope . This harsh reprisal quickly crushed the remaining Molly Maguires movement . The only substantial gain the workers had rom this episode was the knowledge that , lacking labor organization , sporadic violent protest would be met by escalated violence . Public opinion was not sympathetic towards labor violent methods as displayed by the Molly Maguires . But he public was further shocked by some of the harsh practices employed by government agents to crush the movement , as seen the following year in the Great Railroad Strike of 1877 . After incurring a Jay cut earlier that year , railroad workers in West Virginia spontaneously went on strike and blocked the tracks Figure . As word spread of the event , railroad workers across the country joined in sympathy , leaving heir jobs and committing acts of vandalism to show their frustration with the ownership . Local citizens , who in many instances were relatives and friends , were largely sympathetic to the railroad workers demands .

478 18 Industrialization and the Rise of Big Business , cover of Harper August 11 , 1877 , while the Great Railroad Strike was still underway . The most violent outbreak of the railroad strike occurred in Pittsburgh , beginning on July 19 . The governor ordered militiamen from Philadelphia to the Pittsburgh roundhouse to protect railroad property . The militia opened to disperse the angry crowd and killed twenty individuals while wounding another nine . A riot erupted , resulting in hours of looting , violence , and mayhem , and did not die down until the rioters wore out in the hot summer weather In a subsequent skirmish with strikers while trying to escape the roundhouse , militiamen killed another twenty individuals . Violence erupted in Maryland and Illinois as well , and President Hayes eventually sent federal troops into major cities to restore order . This move , a ong with the impending return of cooler weather that brought with it the need for food and fuel , resulted in striking workers nationwide returning to the railroad . The strike had lasted for days , and they had gained nothing but a reputation for violence and aggression that left the public less sympathetic than ever . laborers began to realize that there would be no substantial improvement in their quality of life unti they found a way to better organize themselves . WORKER ORGANIZATION AND THE STRUGGLES OF UNIONS Prior to he Civil War , there were limited efforts to create an organized labor movement on any large scale . With the majority of workers in the country working independently in rural settings , the idea of organized labor was not largely understood . But , as economic conditions changed , people became more aware of the inequities facing factory wage workers . By the early , even farmers began to fully recognize the strength of unity a common cause . Models of Organizing The Knights of Labor and American Federation of Labor In 1866 , delegates representing a variety of different occupations met in Baltimore to form the Labor Union ( The had ambitious ideas about equal rights for African Americans and women , currency reform , and a legally mandated workday . The organization was successful in convincing Congress to adopt the workday for federal employees , but their reach did not progress much further . The Panic of 1873 and the economic recession that followed as a result of overspeculation on railroads and the subsequent closing of several which workers actively sought any employment regardless of the conditions or well as the death of the founder , led to a decline in their efforts . A combination of factors contributed to the debilitating Panic of 1873 , which triggered what the public referred to at the time as the Great Depression of the . Most notably , the railroad boom that had occurred from 1840 to 1870 was rapidly coming to a close . Overinvestment in the industry had extended many investors capital resources in the form of railroad bonds . However , when several economic developments in Europe affected the value of silver in America , which in turn led to a de facto gold standard that shrunk the monetary supply , the amount of cash capital available for railroad investments rapidly declined . Several large business enterprises were left holding their wealth in all but worthless railroad bonds . When Jay Cooke Access for free at .

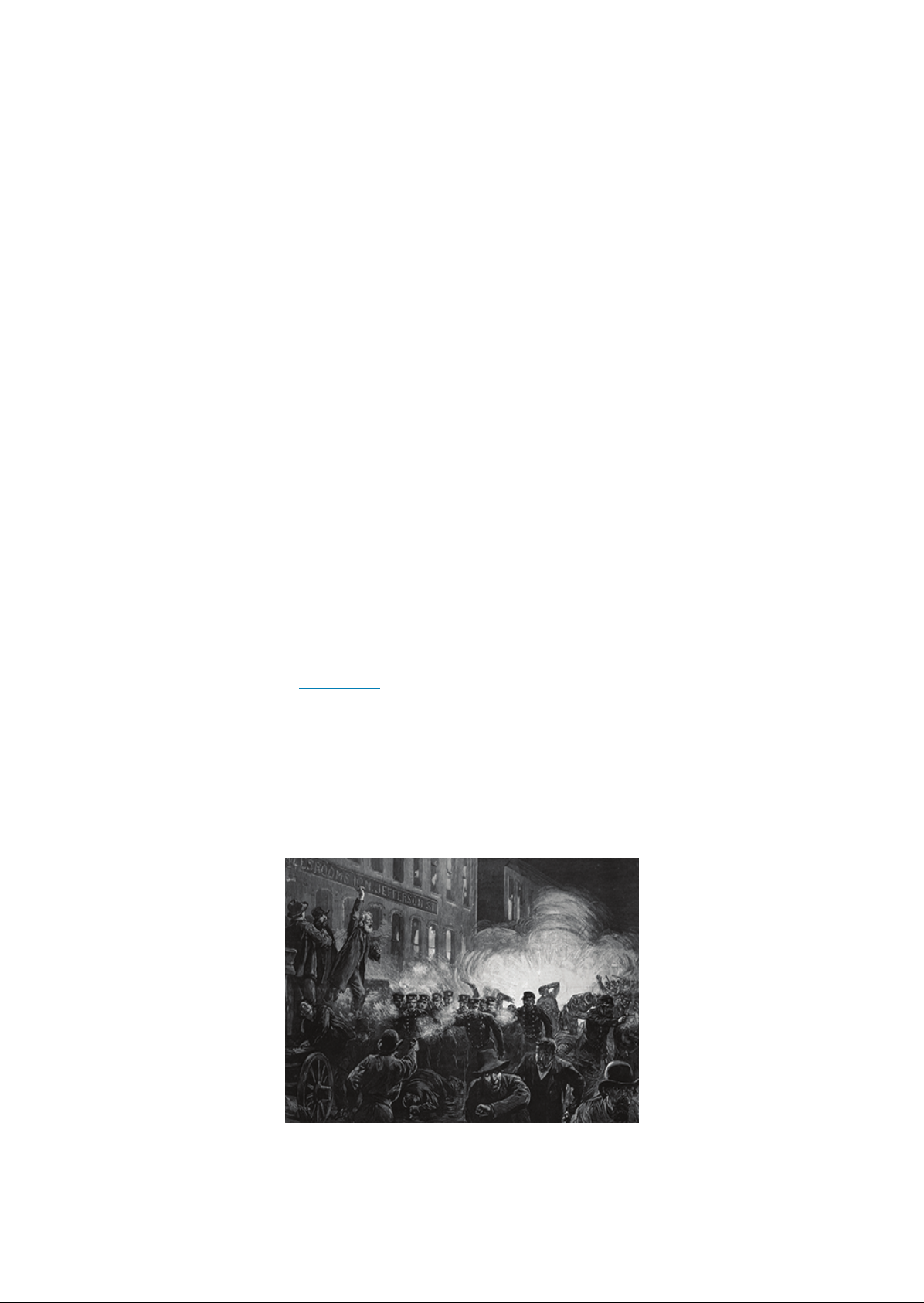

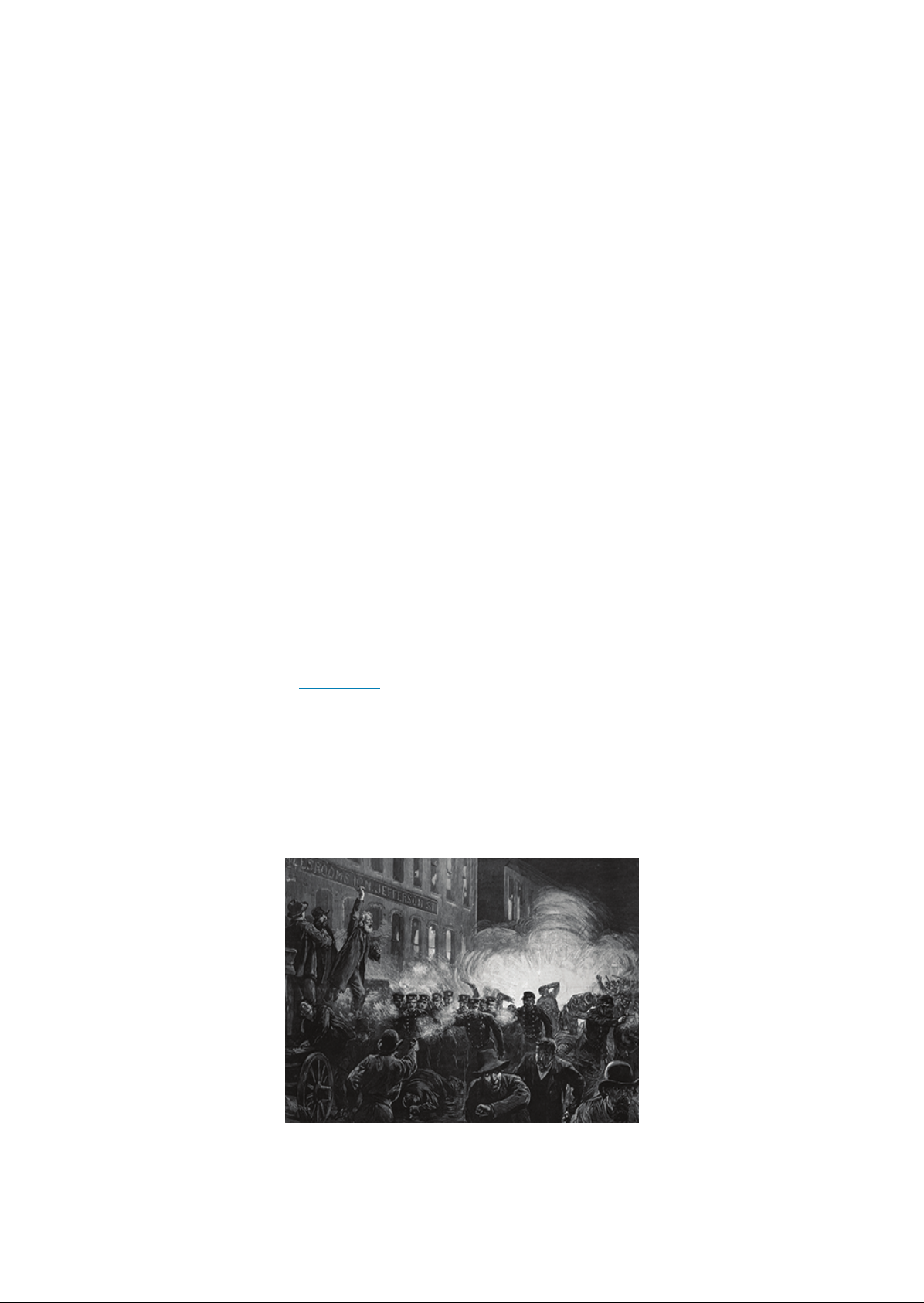

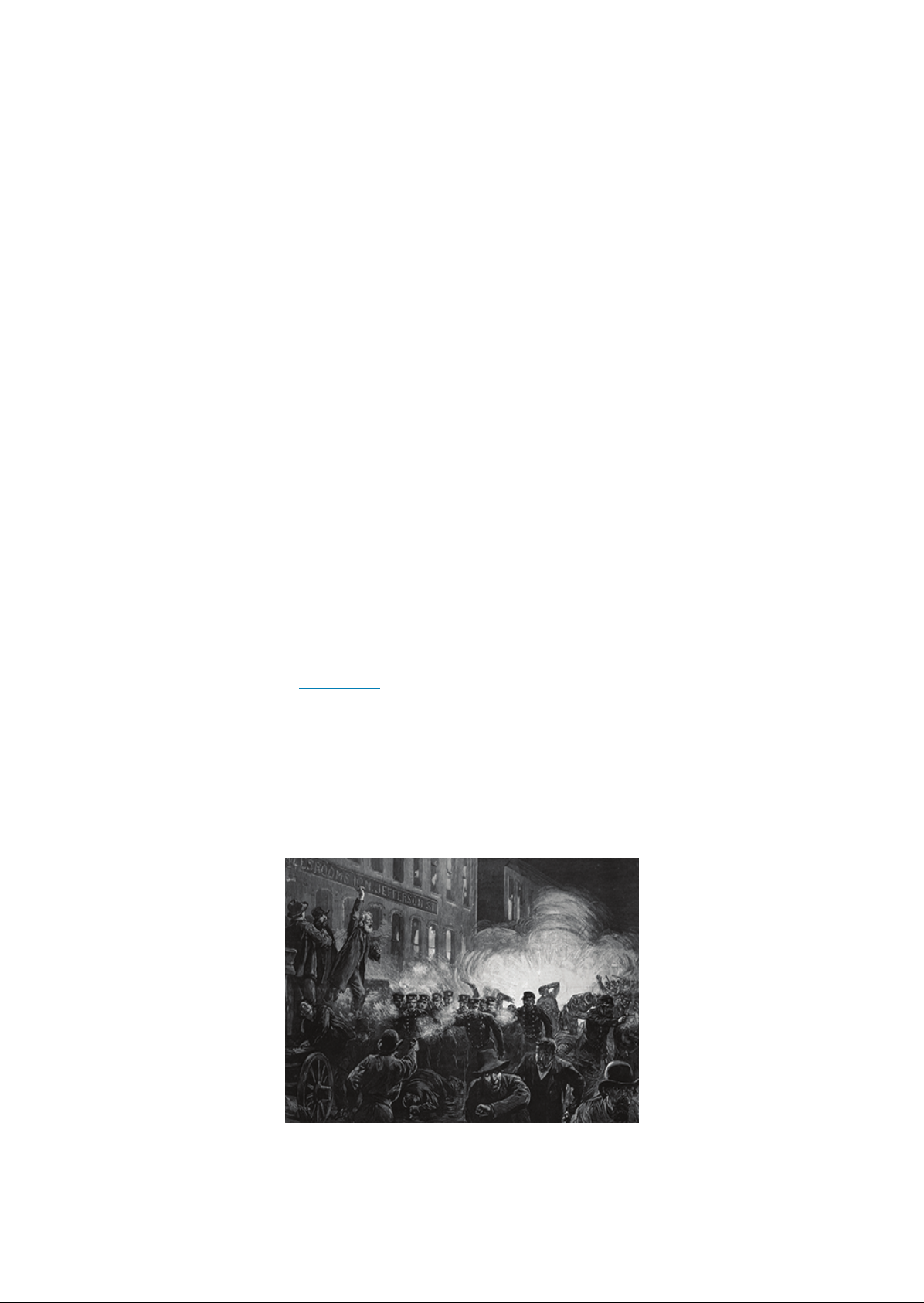

Building Industrial America on the Backs of Labor 479 Company , a leader in the American banking industry , declared bankruptcy on the eve of their plans to the construction of a new transcontinental railroad , the panic truly began . A chain reaction of bank failures culminated with the New York Stock Exchange suspending all trading for ten days at the end of September 1873 . Within a year , over one hundred railroad enterprises had failed within two years , nearly twenty thousand businesses had failed . The loss of jobs and wages sent workers throughout the United States seeking solutions and clamoring for scapegoats . Although the proved to be the wrong effort at the wrong time , in the wake of the Panic of 1873 and the subsequent frustration exhibited in the failed Molly Maguires uprising and the national railroad strike , another , more , labor organization emerged . The Knights of Labor ( KOL ) was more able to attract a sympathetic following than the Molly Maguires and others by widening its base and appealing to more members . Philadelphia tailor Uriah Stephens grew the KOL from a small presence during the Panic of 1873 to an organization of national importance by 1878 . That was the year the KOL held their general assembly , where they adopted a broad reform platform , including a renewed call for an workday , equal pay regardless of gender , the elimination of convict labor , and the creation of greater cooperative enterprises with worker ownership of businesses . Much of the KOL strength came from its concept of One Big Union idea that it welcomed all wage workers , regardless of occupation , with the exception of doctors , lawyers , and bankers . It welcomed women , African Americans , Native Americans , and immigrants , of all trades and skill levels . This was a notable break from the earlier tradition of craft unions , which were highly specialized and limited to a particular group . In 1879 , a new leader , Terence , joined the organization , and he gained even more followers due to his marketing and promotional efforts . Although largely opposed to strikes as effective tactics , through their sheer size , the Knights claimed victories in several railroad strikes in , including one against notorious robber baron Jay Gould , and their popularity consequently rose among workers . By 1886 , the KOL had a membership in excess of . In one night , however , the KOL indeed the momentum of the labor movement as a due to an event known as the Haymarket affair , which occurred on May , 1886 , in Chicago Haymarket Square Figure 1812 . There , an anarchist group had gathered in response to a death at an earlier nationwide demonstration for the workday . At the earlier demonstration , clashes between police and strikers at the International Harvester Company of Chicago led to the death of a striking worker . The anarchist group decided to hold a protest the following night in Haymarket Square , and , although the protest was quiet , the police arrived armed for . Someone in the crowd threw a bomb at the police , killing one and injuring another . The seven anarchists speaking at the protest were arrested and charged with murder . They were sentenced to death , though two were later pardoned and one committed suicide in prison before his execution . FIGURE The Haymarket affair , as it was known , began as a rally for the workday . But when police broke it up , someone threw a bomb into the crowd , causing mayhem . The organizers of the rally , although not responsible , were sentenced to death . The affair and subsequent hangings struck a harsh blow against organized

480 18 Industrialization and the Rise of Big Business , labor . The press immediately blamed the KOL as well as for the Haymarket affair , despite the fact that neither the organization nor had anything to do with the demonstration . Combined with the American public lukewarm reception to organized labor as a whole , the damage was done . The KOL saw its membership decline to barely by the end of 1886 . Nonetheless , during its brief success , the Knights illustrated the potential for success with their model of industrial unionism , which welcomed workers from all trades . AMERICANA The Haymarket Rally On May , recognized internationally as a day for labor celebration , labor organizations around the country engaged in a national rally for the workday . While the number of striking workers varied around the country , estimates are that between and workers protested in New York , Detroit , Chicago , and beyond . In Chicago , clashes between police and protesters led the police to into the crowd , resulting in fatalities . Afterward , angry at the deaths of the striking workers , organizers quickly organized a mass meeting , per the poster below ( Figure . at . II Hill ! had an no nun in . poll . in . um 111 Guilt . uni mi . i amn in . in . FIGURE This poster invited workers to a meeting denouncing the violence at the labor rally earlier in the week . Note that the invitation is written in both English and German , evidence ofthe large role that the immigrant population played in the labor movement . While the meeting was intended to be peaceful , a large police presence made itself known , prompting one of the event organizers to state in his speech , There seems to prevail the opinion in some quarters that this meeting has been called for the purpose of inaugurating a riot , hence these warlike preparations on the part of law and However , let me tell you at the this meeting has not been called for any such purpose . The object of this meeting is to explain the general situation of the movement and to throw light upon various incidents in connection with it . The mayor of Chicago later corroborated accounts of the meeting , noted that it was a peaceful rally , but as it was winding down , the police marched into the crowd , demanding they disperse . Someone in the crowd threw a bomb , killing one policeman immediately and wounding many others , some of whom died later . Despite the aggressive actions of the police , public opinion was strongly against the striking laborers . The New York Times , after the events played out , reported on it with the headline Access for free at .

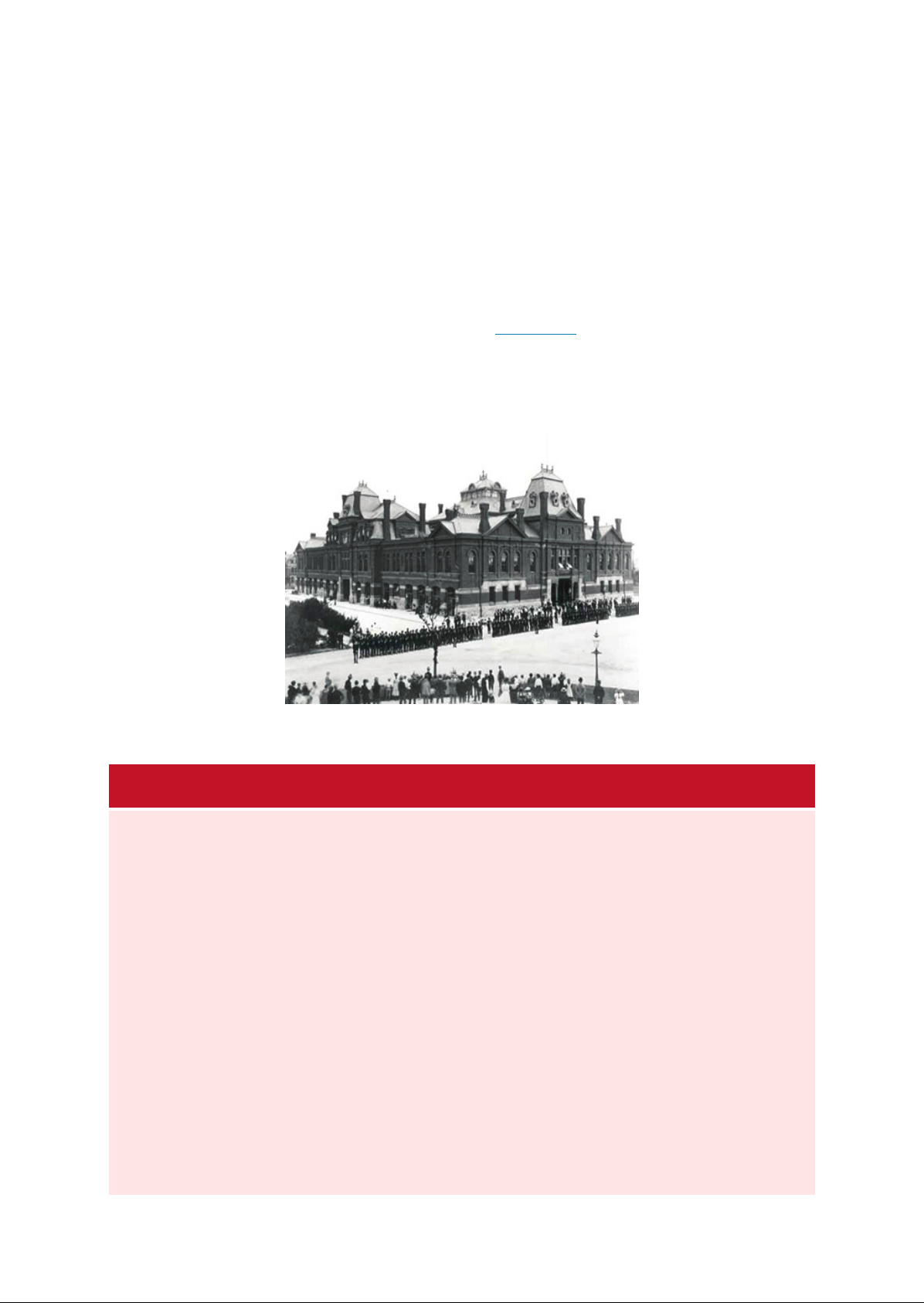

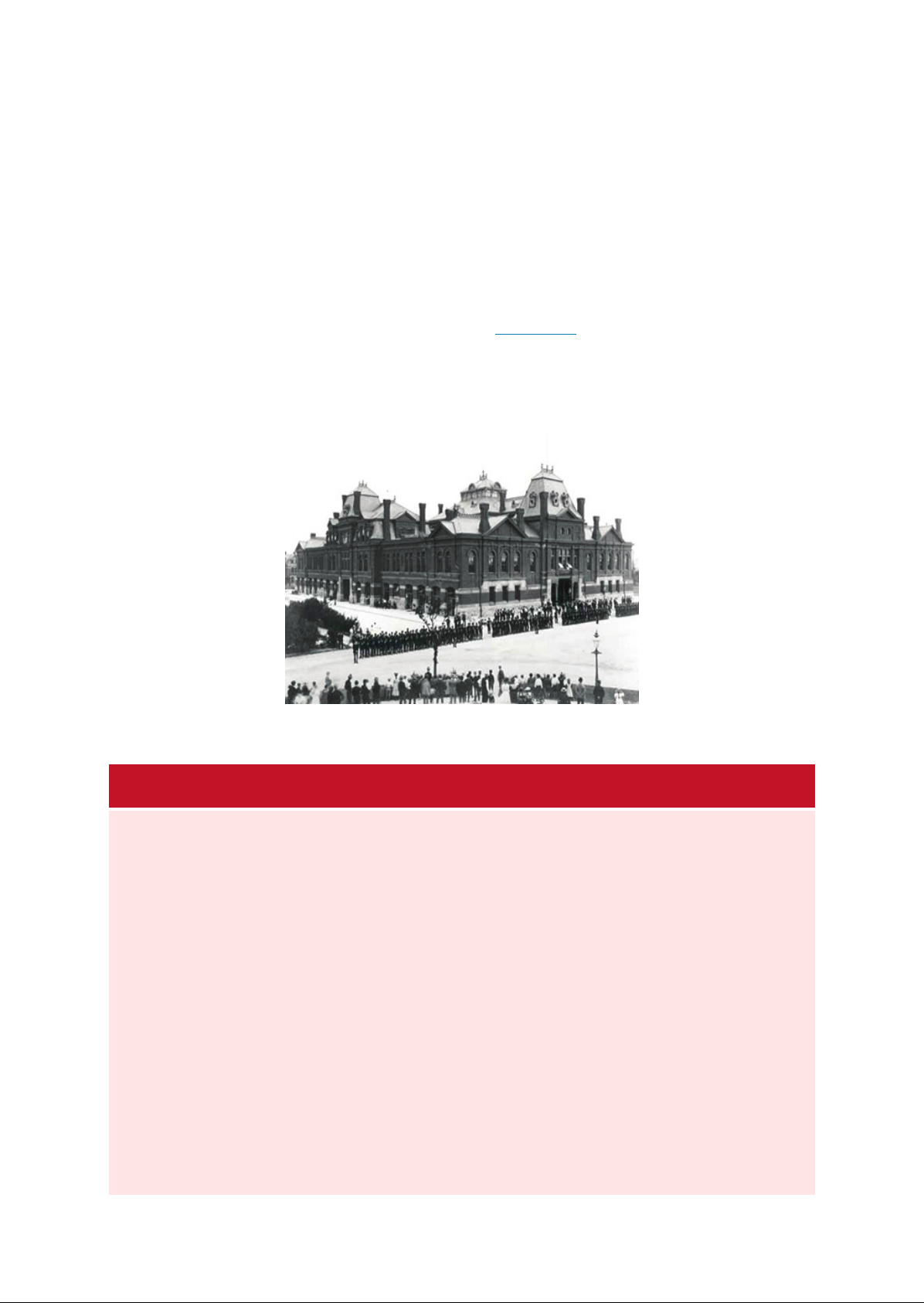

Building Industrial America on the Backs of Labor 481 Rioting and Bloodshed in the Streets of Chicago Police Mowed Down with Other papers echoed the tone and often exaggerated the chaos , undermining organized labor efforts and leading to the ultimate conviction and hanging of the rally organizers . Labor activists considered those hanged after the Haymarket affair to be martyrs for the cause and created an informal memorial at their in Park Forest , Illinois . CLICK AND EXPLORE This article about the Rioting and Bloodshed in the Streets of Chicago ( reveals how the New York Times reported on the Haymarket affair . Assess whether the article gives evidence of the information it lays out . Consider how it portrays the events , and how different , more sympathetic coverage might have changed the response of the general public towards immigrant workers and labor unions . During the effort to establish industrial unionism in the form of the KOL , craft unions had continued to operate . In 1886 , twenty different craft unions met to organize a national federation of autonomous craft unions . This group became the American Federation of Labor ( led by Samuel from its inception until his death in 1924 . More so than any of its predecessors , the focused almost all of its efforts on economic gains for its members , seldom straying into political issues other than those that had a direct impact upon working conditions . The also kept a strict policy of not interfering in each union individual business . Rather , often settled disputes between unions , using the to represent all unions of matters of federal legislation that could affect all workers , such as the workday . By 1900 , the had members by 1914 , its numbers had risen to one million , and by 1920 they claimed four million working members . Still , as a federation of craft unions , it excluded many factory workers and thus , even at its height , represented only 15 percent of the nonfarm workers in the country . As a result , even as the country moved towards an increasingly industrial age , the majority of American workers still lacked support , protection from ownership , and access to upward mobility . The Decline of Labor The Homestead and Pullman Strikes While workers struggled to the right organizational structure to support a union movement in a society that was highly critical of such worker organization , there came two violent events at the close of the nineteenth century . These events , the Homestead Steel Strike of 1892 and tie Pullman Strike of 1894 , all but crushed the labor movement for the next forty years , leaving public opinion of labor strikes lower than ever and workers unprotected . At the Homestead factory of the Carnegie Steel Company , workers ed by the Amalgamated Association of Iron and Steel Workers enjoyed relatively good relations with management until Henry Frick became the factory manager in 1889 . When the union contract was up for renewal in 1892 , a champion of living wages for his left for Scotland and trusted for his strong union manage the negotiations . When no settlement was by June 29 , Frick ordered a lockout of the workers and hired three hundred Pinkerton detectives to pro ect company property . On July , as the Pinkertons arrived on barges on the river , union workers along the shore engaged them in a that resulted in the deaths of three Pinkertons and six workers . One week later , the Pennsylvania militia arrived to escort into the factory to resume production . Although the lockout continued until November , it ended with the union defeated and individual workers asking or their jobs back . A subsequent failed assassination attempt by anarchist Alexander on Frick further strengthened public animosity towards the union . Two years later , in 1894 , the Pullman Strike was another disaster for unionized labor . The crisis began in the company town of Pullman , Illinois , where Pullman sleeper cars were manufactured for America railroads . When the depression of 1893 unfolded in the wake of the failure of several northeastern railroad companies ,

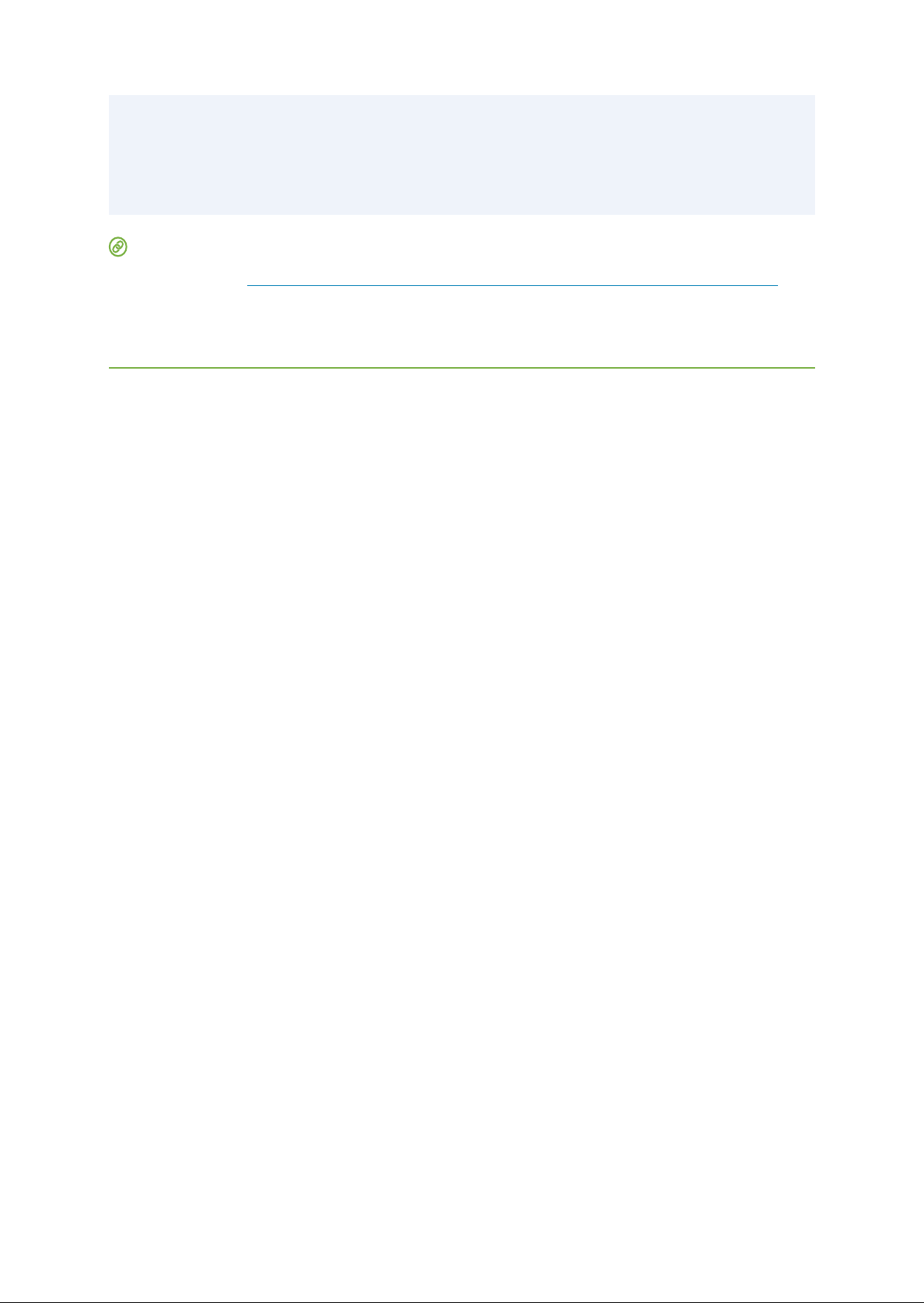

482 18 and the Rise of Big Business , mostly due to and poor , company owner George Pullman three thousand of the factory six thousand employees , cut the remaining workers wages by an average of 25 percent , and then continued to charge the same high rents and prices in the company homes and store where workers were required to live and shop . Workers began the strike on May 11 , when Eugene Debs , the president of the American Railway Union , ordered rail workers throughout the country to stop handling any trains that had Pullman cars on them . In practicality , almost all of the trains fell into this category , and , therefore , the strike created a nationwide train stoppage , right on the heels of the depression of 1893 . Seeking for sending in federal troops , President Grover Cleveland turned to his attorney general , who came up with a solution Attach a mail car to every train and then send in troops to ensure the delivery of the mail . The government also ordered the strike to end when Debs refused , he was arrested and imprisoned for his interference with the delivery of mail . The image below ( Figure shows the standoff between federal troops and the workers . The troops protected the hiring of new workers , thus rendering the strike tactic largely ineffective . The strike ended abruptly on July 13 , with no labor gains and much lost in the way of public ' FIGURE In this photo ofthe Pullman Strike of 1894 , the Illinois National Guard and striking workers face off in front of a railroad building . MY STORY George Estes on the Order of Railroad The following excerpt is a reflection from George Estes , an organizer and member of the Order of Railroad , a labor organization at the end of the nineteenth century . His perspective on the ways that labor and management related to each other illustrates the difficulties at the heart of their negotiations . He notes that , in this era , the two groups saw each other as enemies and that any gain by one was automatically a loss by the other . I have always noticed that things usually have to get pretty bad before they get any better . When inequities pile up so high that the burden is more than the underdog can bear , he gets his dander up and things begin to happen . It was that way with the problem . These exploited individuals were determined to get for themselves better working pay , shorter hours , less work which might not properly be classed as telegraphy , and the high and mighty Fillmore railroad company president was not goingto stop them . It was a bitter . At the outset , Fillmore let it be known , by his actions and comments , that he held the in the utmost contempt . With the papers crammed each day with news of labor with two great labor factions at each other throats , I am reminded of a parallel in my own early and more active career . Shortly before the turn ofthe Access for free at .

A New American Consumer Culture 483 century , in 1898 and 1899 to be more , I occupied a position with regard to a certain class of skilled labor , comparable to that held bythe and Greens of today . I refer , of course , to the and station agents . These of the no regular hours , performed a multiplicity of duties , and , considering the service they rendered , were sorely and inadequately paid . A telegrapher day included a considerable number of chores that probably never did or will do in the course of a day work . He used to clean and lanterns , block lights , etc . Used to do the janitor work around the small town depot , stoke the stove of the , sweep the floors , picking up papers and litter . Today , capital and labor seem to understand each other better than they did a generation or so ago . Capital is out to make money . So is each is willingto grant the other a certain amount of tolerant leeway , just so he doesn go too far . In the old days there was a breach as wide as the separating capital and labor . It was money altogether in those days , it was a matter of principle . Capital and labor couldn see eye to eye on a single point . Every gain that either made was at the expense ofthe other , and was fought tooth and nail . No difference seemed ever possible of amicable settlement . Strikes were riots . Murder and mayhem was common . Railroad labor troubles were frequent . The railroads , in the nineties , were the country largest employers . They were so big , so powerful , so perfectly organized mean so in accord among themselves as to what treatment they felt like offering the man who worked for it was extremely for labor to gain a single advantage in the struggle for better conditions . Estes , interview with Andrew , 1938 A New American Consumer Culture LEARNING OBJECTIVES By the end of this section , you will be able to Describe the characteristics of the new consumer culture that emerged at the end of the nineteenth century Despite the challenges workers faced in their new roles as wage earners , the rise of industry in the United States allowed people to access and consume goods as never before . The rise of big business had turned America into a culture of consumers desperate for and leisure commodities , where people could expect to everything they wanted in shops or by mail order . Gone were the days where the small general store was the only option for shoppers at the end of the nineteenth century , people could take a train to the city and shop in large department stores like Macy in New York , Gimbel in Philadelphia , and Marshall Field in Chicago . Chain stores , like A and Woolworth , both of which opened in the , offered options to those who lived farther from major urban areas and clearly catered to classes other than the wealthy elite . Industrial advancements contributed to this proliferation , as new construction techniques permitted the building of stores with higher ceilings for larger displays , and the production of larger sheets of plate glass lent themselves to the development of larger store windows , glass countertops , and display cases where shoppers could observe a variety of goods at a glance . Frank Baum , of Wizard of Oz fame , later founded the National Association of Window Trimmers in 1898 , and began publishing The Store Window journal to advise businesses on space usage and promotion . Even families in rural America had new opportunities to purchase a greater variety of products than ever before , at ever decreasing prices . Those far from chain stores could from the newly developed business of catalogs , placing orders by telephone . Montgomery Ward established the business in 1872 , with Sears , Roebuck Company following in 1886 . Sears distributed over catalogs annually by 1897 , and later broke the one million annual mark in 1907 . Sears in particular understood that farmers and rural Americans sought alternatives to the higher prices and credit purchases they were forced to endure at country stores . By clearly stating the prices in his catalog , Richard Sears steadily increased his company image of their catalog serving as the consumer bible . In the process ,

484 18 and the Rise of Big Business , Sears , Roebuck Company supplied much of America hinterland with products ranging from farm supplies to bicycles , toilet paper to automobiles , as seen below in a page from the catalog ( Figure 1815 ) I , cu , mum , nu FIGURE This page from the Sears , Roebuck catalog illustrates how luxuries that would only belongto wealthy city dwellers were now available by mail order to those all around the country . The tremendous variety of goods available for sale required businesses to compete for customers in ways they had never before imagined . Suddenly , instead of a single option for clothing or shoes , customers were faced with dozens , whether ordered by mail , found at the local chain store , or lined up in massive rows at department stores . This new level of competition made advertising a vital component of all businesses . By 1900 , American businesses were spending almost 100 million annually on advertising . Competitors offered new and improved models as frequently as possible in order to generate interest . From toothpaste and mouthwash to books on entertaining guests , new goods were constantly offered . Newspapers accommodated the demand for advertising by shifting their production to include advertisements , as opposed to the traditional column width , advertisements that dominated century newspapers ( similar to advertisements in today publications ) Likewise , professional advertising agencies began to emerge in the 18803 , with experts in consumer demand bidding for accounts with major . It may seem strange that , at a time when wages were so low , people began buying readily however , the slow emergence of a middle class by the end of the century , combined with the growing practice of buying on credit , presented more opportunities to take part in the new consumer culture . Stores allowed people to open accounts and purchase on credit , thus securing business and allowing consumers to buy without ready cash . Then , as today , the risks of buying on credit led many into debt . As advertising expert Roland described in his Parable on the Democracy of Goods , in an era when access to products became more important than access to the means of production , Americans quickly accepted the notion that they could live a better lifestyle by purchasing the right clothes , the best hair cream , and the shiniest shoes , regardless of their class . For better or worse , American consumerism had begun . Access for free at .

A New American Consumer Culture 485 AMERICANA Advertising in the Industrial Age Credit , Luxury , and the Advent of New and Improved Before the industrial revolution , most household goods were either made at home or purchased locally , with limited choices . By the end of the nineteenth century , factors such as the population move towards urban centers and the expansion ofthe railroad changed how Americans shopped for , and perceived , consumer goods . As mentioned above , advertising took off , as businesses competed for customers . Many of the elements used widely in advertisements are familiar . Companies sought to sell luxury , safety , and , as the ad for the typewriter below shows ( Figure , the allure ofthe model . One advertising tactic that tru took off in this era was the option to purchase on credit . Forthe first time , mail order and mass production meant that the aspiring middle class could purchase items that could only be owned previously by the wealthy . Whi there was a societal stigma for buying everyday goods on credit , certain items , such as furniture or pianos , were considered an investment in the move toward entry into the middle class . THE 1892 MODEL on nu Remington Typewriter IS NOW ON THE MARKET . was I . FIGURE This typewriter , like others of the era , tried to lure customers by offering a new model . Additionally , farmers and housewives purchased farm equipment and sewing machines on credit , considering these items investments ratherthan . For women , the purchase of a sewing machine meant that a shirt could be made in one hour , instead of fourteen . The Singer Sewing Machine Company was one of the most aggressive at pushing purchase on credit . They advertised widely , and their Dollar Down , Dollar a Week campaign made them one of the companies in the country . For workers earning lower wages , these easy credit terms meant that the lifestyle was within their reach . Of course , it also meant they were in debt , and changes in wages , illness , or other unexpected expenses could wreak havoc on a household tenuous . Still , the opportunity to own new and luxurious products was one that many Americans , improve their place in society , could not resist .

486 18 Key Terms Key Terms Haymarket affair the rally and subsequent riot in which several policemen were killed when a bomb was thrown at a peaceful workers rights rally in Chicago in 1886 holding company a central corporate entity that controls the operations of multiple companies by holding the majority of stock for each enterprise horizontal integration method of growth wherein a company grows through mergers and acquisitions of similar companies Molly Maguires a secret organization made up of Pennsylvania coal miners , named for the famous Irish patriot , which worked through a series of scare tactics to bring the plight of the miners to public attention monopoly the ownership or control of all enterprises comprising an entire industry robber baron a negative term for the big businessmen who made their fortunes in the massive railroad boom of the late nineteenth century management mechanical engineer Fredrick Taylor management style , also called management , which divided manufacturing tasks into short , repetitive segments and encouraged factory owners to seek and over any of personal interaction social Darwinism Herbert Spencer theory , based upon Charles Darwin theory , which held that society developed much like plant or animal life through a process of evolution in which the most and capable enjoyed the greatest material and social success trust a legal arrangement where a small group of trustees have legal ownership of a business that they operate for the of other investors vertical integration a method of growth where a company acquires other companies that include all aspects of a product lifecycle from the creation of the raw materials through the production process to the delivery of the product Summary Inventors of the Age Inventors in the late nineteenth century the market with new technological advances . Encouraged by Great Britain Industrial Revolution , and eager for economic development in the wake of the Civil War , business investors sought the latest ideas upon which they could capitalize , both to transform the nation as well as to make a personal . These inventions were a key piece of the massive shift towards industrialization that followed . For both families and businesses , these inventions eventually represented a fundamental change in their way of life . Although the technology spread slowly , it did spread across the country . Whether it was a company that could now produce ten times more products with new factories , or a household that could communicate with distant relations , the old way of doing things was disappearing . Communication technologies , electric power production , and steel production were perhaps the three most developments of the time . While the two affected both personal lives and business development , the latter business growth and foremost , as the ability to produce large steel elements and led to permanently changes in the direction of industrial growth . From Invention to Industrial Growth As the three tycoons in this section illustrate , the end of the nineteenth century was a period in history that offered tremendous rewards to those who had the right combination of skill , ambition , and luck . Whether millionaires like Carnegie or Rockefeller , or born to wealth like Morgan , these men were the that turned inventors ideas into industrial growth . Steel production , in particular , but also oil techniques and countless other inventions , changed how industries in the country could operate , allowing them to grow in scale and scope like never before . It is also critical to note how these different men managed their businesses and ambition . Where Carnegie felt Access for free at .

18 Review Questions 487 strongly that it was the job of the wealthy to give back in their lifetime to the greater community , his fellow tycoons did not necessarily agree . Although he contributed to many philanthropic efforts , Rockefeller success was built on the backs of ruined and bankrupt companies , and he came to be condemned by progressive reformers who questioned the impact on the working class as well as the dangers of consolidating too much power and wealth into one individual hands . Morgan sought wealth strictly through the investment in , and subsequent purchase of , others hard work . Along the way , the models of management they and vertical integration , trusts , holding companies , and investment commonplace in American businesses . Very quickly , large business enterprises fell under the control of fewer and fewer individuals and trusts . In sum , their ruthlessness , their ambition , their generosity , and their management made up the workings of Americas industrial age . Building Industrial America on the Backs of Labor After the Civil War , as more and more people crowded into urban areas and joined the ranks of wage earners , the landscape of American labor changed . For the time , the majority of workers were employed by others in factories and in the cities . Factory workers , in particular , suffered from the inequity of their positions . Owners had no legal restrictions on exploiting employees with long hours in dehumanizing and poorly paid work . Women and children were hired for the lowest possible wages , but even men wages were barely enough upon which to live . Poor working conditions , combined with few substantial options for relief , led workers to frustration and sporadic acts of protest and violence , acts that rarely , if ever , gained them any lasting , positive effects . Workers realized that change would require organization , and thus began early labor unions that sought to win rights for all workers through political advocacy and owner engagement . Groups like the National Labor Union and Knights of Labor both opened their membership to any and all wage earners , male or female , Black or White , regardless of skill . Their approach was a departure from the craft unions of the very early nineteenth century , which were unique to their individual industries . While these organizations gained members for a time , they both ultimately failed when public reaction to violent labor strikes turned opinion against them . The American Federation of Labor , a loose of different unions , grew in the wake of these universal organizations , although negative publicity impeded their work as well . In all , the century ended with the vast majority of American laborers unrepresented by any collective or union , leaving them vulnerable to the power wielded by factory ownership . A New American Consumer Culture While tensions between owners and workers continued to grow , and wage earners struggled with the challenges of industrial work , the culture of American consumerism was changing . Greater choice , easier access , and improved goods at lower prices meant that even Americans , whether rural and shopping via mail order , or urban and shopping in large department stores , had more options . These increased options led to a rise in advertising , as businesses competed for customers . Furthermore , the opportunity to buy on credit meant that Americans could have their goods , even without ready cash . The result was a population that had a better standard of living than ever before , even as they went into debt or worked long factory hours to pay for it . Review Questions . Which of these was nola successful invention of the era ?

sewing machines movies with sound frozen foods typewriters 488 18 Review Questions . What was the major advantage of alternating current power invention ?