Go West Young Man! Westward Expansion, 1840-1900

Explore the Go West Young Man! Westward Expansion, 1840-1900 study material pdf and utilize it for learning all the covered concepts as it always helps in improving the conceptual knowledge.

Go West Young Man! Westward Expansion, 1840-1900 PDF Download

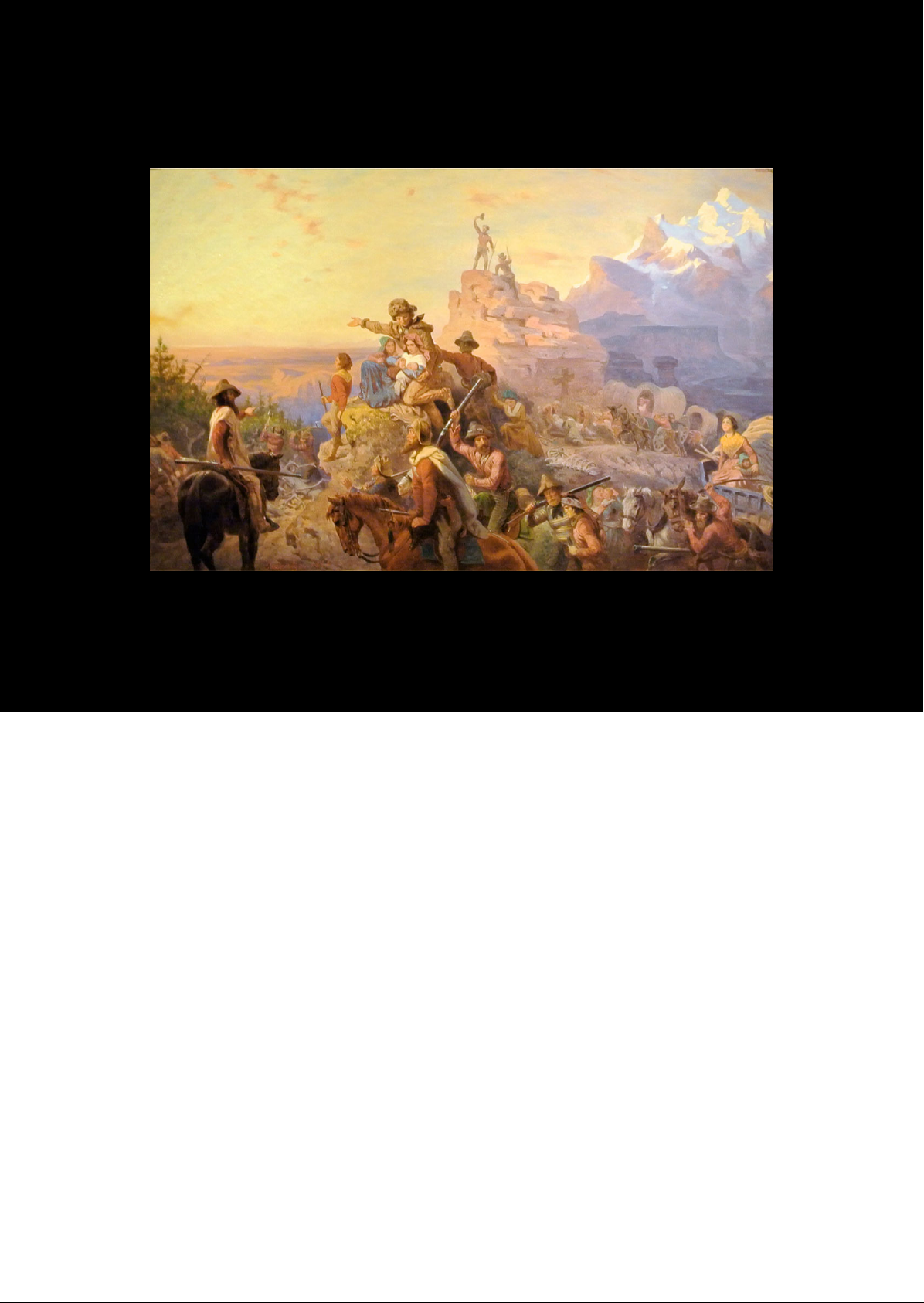

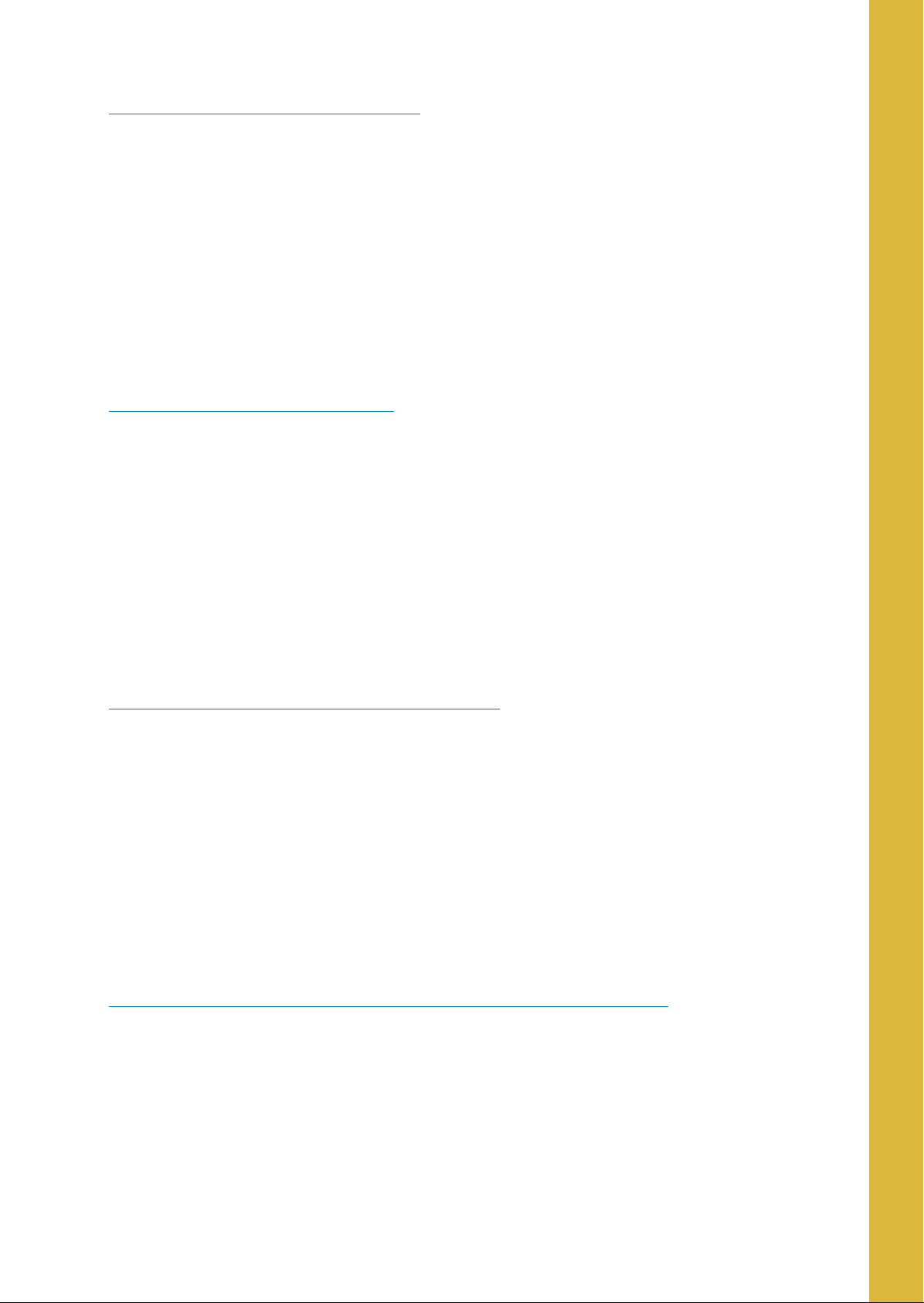

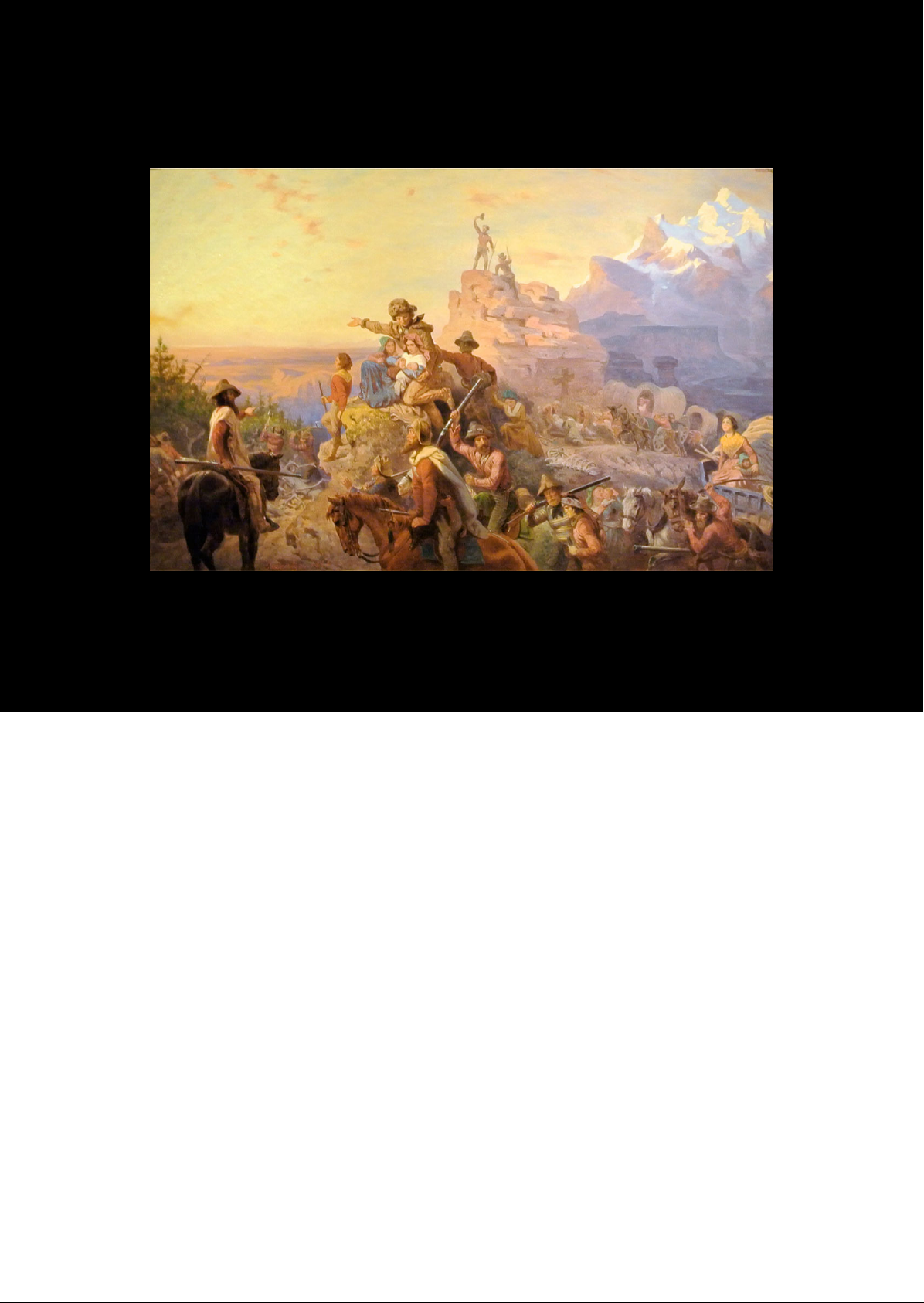

Go West Young Man ! Westward Expansion , FIGURE A widely held belief in the nineteenth century contended that Americans had a divine right and responsibility to settle the West with Protestant democratic values . Newspaper editor Horace Greely , who coined the phrase Go west , young man , encouraged Americans to this dream . Artists ofthe day depicted this western expansion in idealized landscapes that bore little resemblance to the of life on the trail . CHAPTER OUTLINE The Westward Spirit Dreams and Realities Making a Living in Gold and Cattle The on American Indian Life and Culture The of Expansion on Chinese Immigrants and Hispanic Citizens INTRODUCTION In the middle of the nineteenth century , farmers in the Old West land across the Allegheny Moun in to hear about the opportunities to be found in the New They had long believed that the land west of the Mississippi was a great desert , for human habitation . But now , the federal government was encouraging them to join the migratory stream westward to this unknown land . For a of reasons , Americans increasingly felt compelled to their Manifest Destiny , a phrase that came to mean that they were expected to spread across the land given to them by God and , most importantly , spread predominantly American values to the frontier . With great ation , hundreds , and then hundreds of thousands , of settlers packed their lives into wagons and set out , following the Oregon , California , and Santa Fe Trails , to seek a new life in the West . They imagined open lands , economic opportunity , and greater freedom to fulfill the democratic vision originally promoted by Thomas Jefferson despite Native American communities living in the region . Whatever their motivation , the great migration was underway . The American pioneer spirit was born .

436 17 Go West Young Man ! Westward Expansion , The Westward Spirit LEARNING OBJECTIVES By the end ofthis section , you will be able to Explain the evolution of American views about westward migration in the century Analyze the ways in which the federal government facilitated Americans westward migration in the nineteenth century , Dawes Art 71 and amm la settlers 1873 1887 I I I I I I 1848 1862 1869 1876 1882 California and Emir of crime mun Railway Art Am passed , might FIGURE ( credit barbed wire of work by the , Department of Commerce ) While a small number of settlers had pushed westward before the century , the land west of the Mississippi was largely unexplored by the United States . Most Americans , if they thought of it at all , viewed this territory as an arid wasteland suitable only for American Indians . The reflections of early explorers who conducted treks throughout the West tended to this belief . Major Stephen Harriman Long , who commanded an expedition through Missouri and into the Yellowstone region in , frequently described the Great Plains as an arid and useless region , suitable as nothing more than a great American desert . But , beginning in the , a combination of economic opportunity and ideological encouragement changed the way Americans thought of the West . The federal government offered a number of incentives , making it viable for Americans to take on the challenge of seizing these rough lands from their Native American and Hispanic owners . Still , most Americans who went west needed some security at the outset of their journey even with government aid , the truly poor could not make the trip . The cost of moving an entire family westward , combined with the risks as well as the questionable chances of success , made the move prohibitive for most . While the economic Panic of 1837 led many to question the promise of urban America , and thus turn their focus to the promise of commercial farming in the West , the Panic also resulted in many lacking the resources to make such a commitment . For most , the dream to Go west , young man remained . While much of the basis for westward expansion was economic , there was also a more philosophical reason , which was bound up in the American belief that the the Indigenous peoples who populated destined to come under the civilizing rule of settlers and their superior technology , most notably railroads and the telegraph . While the extent to which that belief was a heartfelt motivation held by most Americans , or simply a rationalization of the conquests that followed , remains debatable , the physical and followed this western migration left scars on the country that are still felt today . MANIFEST DESTINY The concept of Manifest Destiny found its roots in the traditions of territorial expansion upon which the nation itself was founded . This phrase , which implies divine encouragement for territorial expansion , was coined by magazine editor John in 1845 , when he wrote in the United States Magazine and Democratic it was our manifest destiny to overspread the continent allotted by Providence for the free development of our multiplying millions . Although the context of original Access for free at .

The Westward Spirit 437 article was to encourage expansion into the newly acquired Texas territory , the spirit it invoked would subsequently be used to encourage westward settlement throughout the rest of the nineteenth century . Land developers , railroad magnates , and other investors capitalized on the notion to encourage westward settlement for their own . Soon thereafter , the federal government encouraged this inclination as a means to further develop the West during the Civil War , especially at its outset , when concerns over the possible expansion of slavery deeper into western territories was a legitimate fear . The idea was simple Americans were indeed divinely expand democratic institutions throughout the continent . As they spread their culture , thoughts , and customs , they would , in the process , expose the native inhabitants to Protestant institutions and , more importantly , new ways to develop the land . Sullivan may have coined the phrase , but the concept had preceded him Throughout the , politicians and writers had stated the belief that the United States was destined to rule the continent . Sullivan words , which resonated in the popular press , matched the economic and political goals of a federal government increasingly committed to expansion . Manifest Destiny in Americans minds their right and duty to govern any other groups they encountered during their expansion , as well as absolved them of any questionable tactics they employed in the process . While the commonly held view of the day was of a relatively empty frontier , waiting for the arrival of the settlers who could properly exploit the vast resources for economic gain , the reality was quite different . Hispanic communities in the Southwest , diverse tribes throughout the western states , as well as other settlers from Asia and Western Europe already lived in many parts of the country . American expansion would necessitate a far more complex and involved exchange than simply empty space . Still , in part as a result of the spark lit by Sullivan and others , waves of Americans and recently arrived immigrants began to move west in wagon trains . They travelled along several trails the Oregon Trail , then later the Santa Fe and California Trails , among others . The Oregon Trail is the most famous of these western routes . Two thousand miles long and barely passable on foot in the early nineteenth century , by the , wagon trains were a common sight . Between 1845 and 1870 , considered to be the height of migration along the trail , over settlers followed this path west from Missouri ( Figure ) Despite emphasis on with Native Americans in movies , tribe members often served as guides or traded with the emigrants . FIGURE Hundreds of thousands of people travelled west on the Oregon , California , and Santa Fe Trails , but their numbers did not ensure their safety . Illness , starvation , and other real and made survival hard . But despite popular images of wagons circled to defend against Native American attacks , more Native people than emigrants died from the violence associated with the overland routes . credit National Archives and Records Administration )

438 17 Go West Young Man ! Westward Expansion , DEFINING AMERICAN Who Will Set Limits to Our Onward March ?

America is destined for better deeds It is our unparalleled glory that we have no reminiscences of battle , but in defense sic of humanity , ofthe oppressed of all nations , of the rights of conscience , the rights of personal enfranchisement . Our annals describe no scenes of horrid carnage , where men were led on by hundreds of thousands to slay one another , dupes and victims to emperors , kings , nobles , demons in the human form called heroes . We have had patriots to defend our homes , our liberties , but no aspirants to crowns or thrones nor have the American people ever suffered themselves to be led on by wicked ambition to depopulate the land , to spread desolation far and wide , that a human being might be placed on a seat of supremacy . The expansive future is our arena , and for our history . We are entering on its untrodden space , with the truths of God in our minds , objects in our hearts , and with a clear conscience unsullied by the past . We are the nation of human progress , and who will , what can , set limits to our onward march ?

Providence is with us , and no earthly power can . 1839 Think about how this quotation resonated with different groups of Americans at the time . When looked at through today lens , the actions of the settlers were fraught with brutality and racism . At the time , however , many settlers felt they were at the pinnacle of democracy , and that with no aristocracy or ancient history , America was a new world where anyone could succeed . Even then , consider how the phrase anyone was restricted by race , gender , and nationality . Also consider how the idea of untrodden space ignores groups of people . CLICK AND EXPLORE Visit Across the Plains in 64 ( details ) to follow one family making their way westward from Iowa to Oregon . Click on a few of the entries and see how the author describes their journey , from the expected to the surprising . FEDERAL GOVERNMENT ASSISTANCE To assist the settlers in their move westward and transform the migration from a trickle into a steady , Congress passed two pieces of legislation in 1862 the Homestead Act and the Railway Act . Born largely out of President Abraham Lincoln growing concern that a potential Union defeat in the early stages of the Civil War might result in the expansion of slavery westward , Lincoln hoped that such laws would encourage the expansion of a free soil mentality across the West . The Homestead Act allowed any head of household , or individual over the age of unmarried receive a parcel of 160 acres for only a nominal fee . All that recipients were required to do in exchange was to improve the land within a period of years of taking possession . The standards for improvement were minimal Owners could clear a few acres , build small houses or barns , or maintain livestock . Under this act , the government transferred over 270 million acres of public domain land to private citizens . The Railway Act was pivotal in helping settlers move west more quickly , as well as move their farm products , and later cattle and mining deposits , back east . The of many railway initiatives , this act commissioned the Union Railroad to build new track west from Omaha , Nebraska , while the Central Railroad moved east from Sacramento , California . The law provided each company with ownership of all public lands within two hundred feet on either side of the track laid , as well as additional land grants and Access for free at .

The Westward Spirit 439 payment through load bonds , prorated on the of the terrain it crossed . Because of these provisions , both companies made a , whether they were crossing hundreds of miles of open plains , or working their way through the Sierra Nevada Mountains of California . As a result , the nation transcontinental railroad was completed when the two companies connected their tracks at Promontory , Utah , in the spring of 1869 . Other tracks , including lines radiating from this original one , subsequently created a network that linked all corners of the nation Figure . FIGURE The Golden Spike connecting the country by rail was driven into the ground in Promontory , Utah , in 1869 . The completion of the transcontinental railroad dramatically changed the tenor of travel in the country , as people were able to complete in a week a route that had previously taken months . In addition to legislation designed to facilitate western settlement , the government assumed an active role on the ground , building numerous forts throughout the West to aid settlers during their migration . Forts such as Fort Laramie in Wyoming ( built in 1834 ) and Fort Apache in Arizona ( 1870 ) aimed to facilitate trade and limit between migrants and local American Indian tribes . Others located throughout Colorado and Wyoming became important trading posts for miners and fur trappers . Those built in Kansas , Nebraska , and the served primarily to provide relief for farmers during times of drought or related hardships . Forts constructed along the California coastline provided protection in the wake of the War as well as during the American Civil War . These locations subsequently serviced the Navy and provided important support for growing trade routes . Whether as army posts constructed to aid American migration , or as trading posts to further facilitate the development of the region , such forts proved to be vital contributions to westward migration . WHO WERE THE SETTLERS ?

In the nineteenth century , as today , it took money to relocate and start a new life . Due to the initial cost of relocation , land , and supplies , as well as months of preparing the soil , planting , and subsequent harvesting before any produce was ready for market , the original wave of western settlers along the Oregon Trail in the and consisted of moderately prosperous , White , farming families of the East . But the passage of the Homestead Act and completion of the transcontinental railroad meant that , by 1870 , the possibility of western migration was opened to Americans of more modest means . What started as a trickle became a steady of migration that would last until the end of the century . Nearly settlers had made the trek westward by the height of the movement in 1870 . The vast majority were men , although families also migrated , despite incredible hardships for women with young children . More recent immigrants also migrated west , with the largest numbers coming from Northern Europe and Canada . Germans , Scandinavians , and Irish were among the most common . These ethnic groups tended to settle close together , creating strong rural communities that mirrored the way of life they had left behind . According to Census Bureau records , the number of Scandinavians living in the United States during the second half of the nineteenth century exploded , from barely in 1850 to over million in 1900 . During that same time

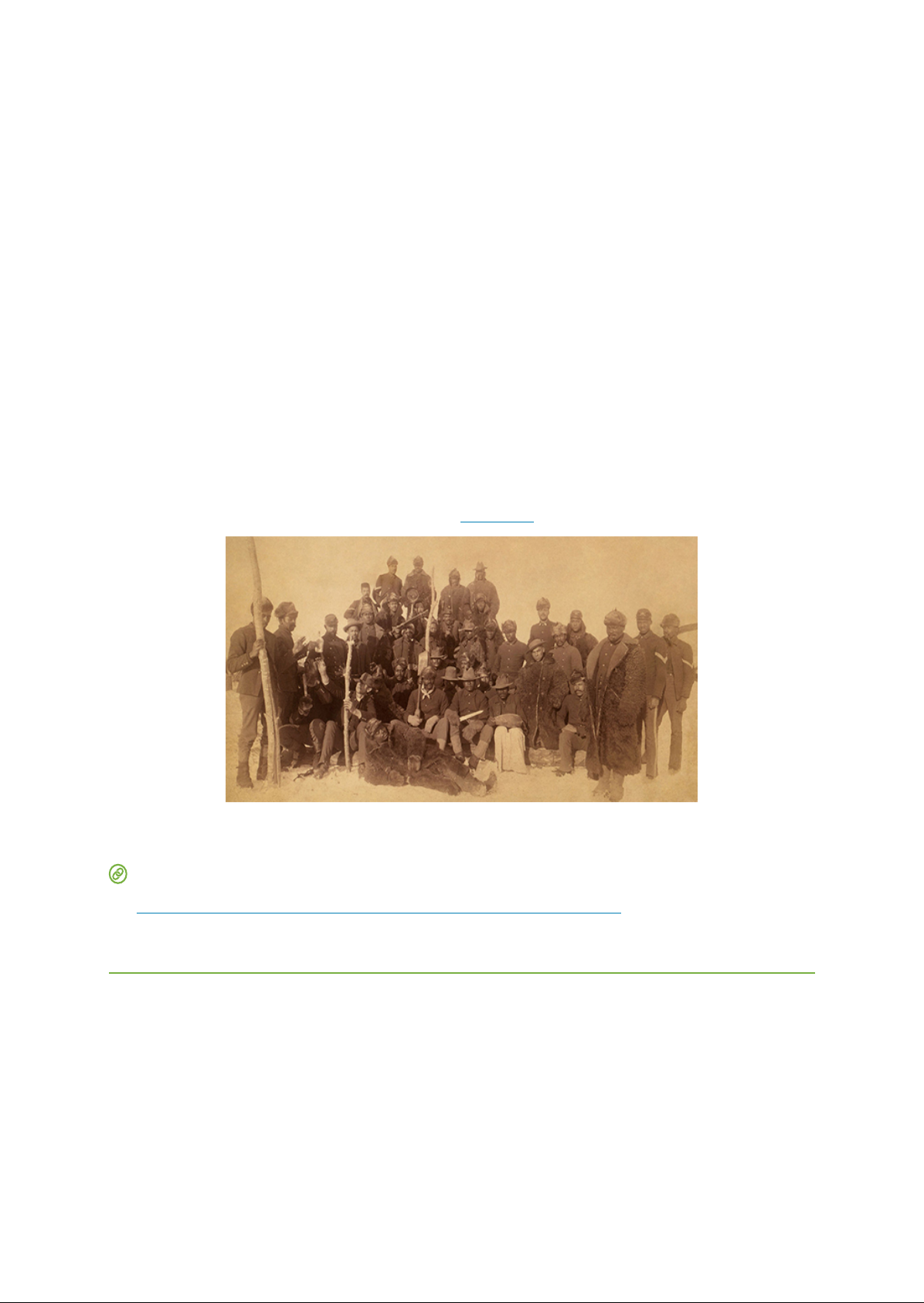

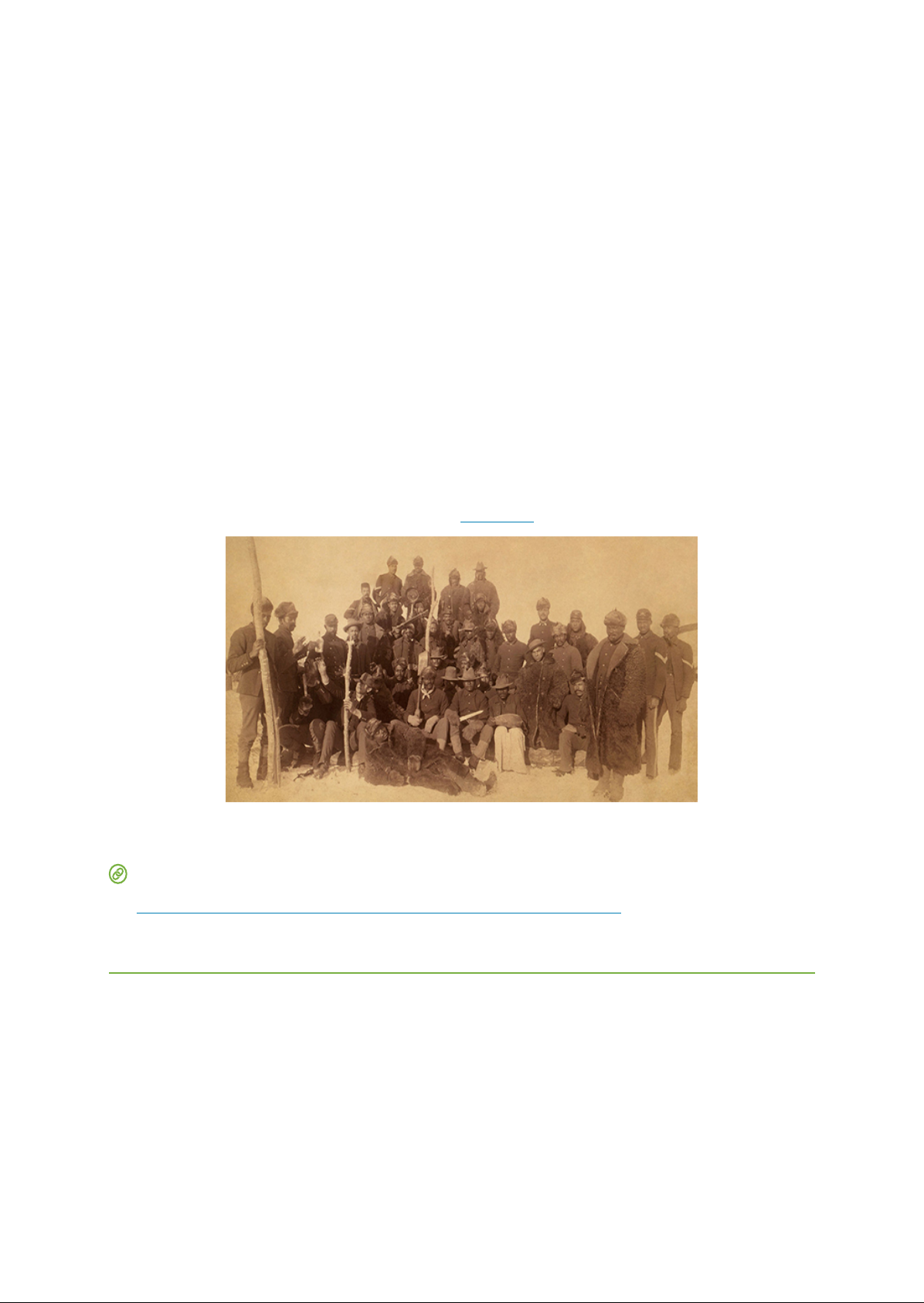

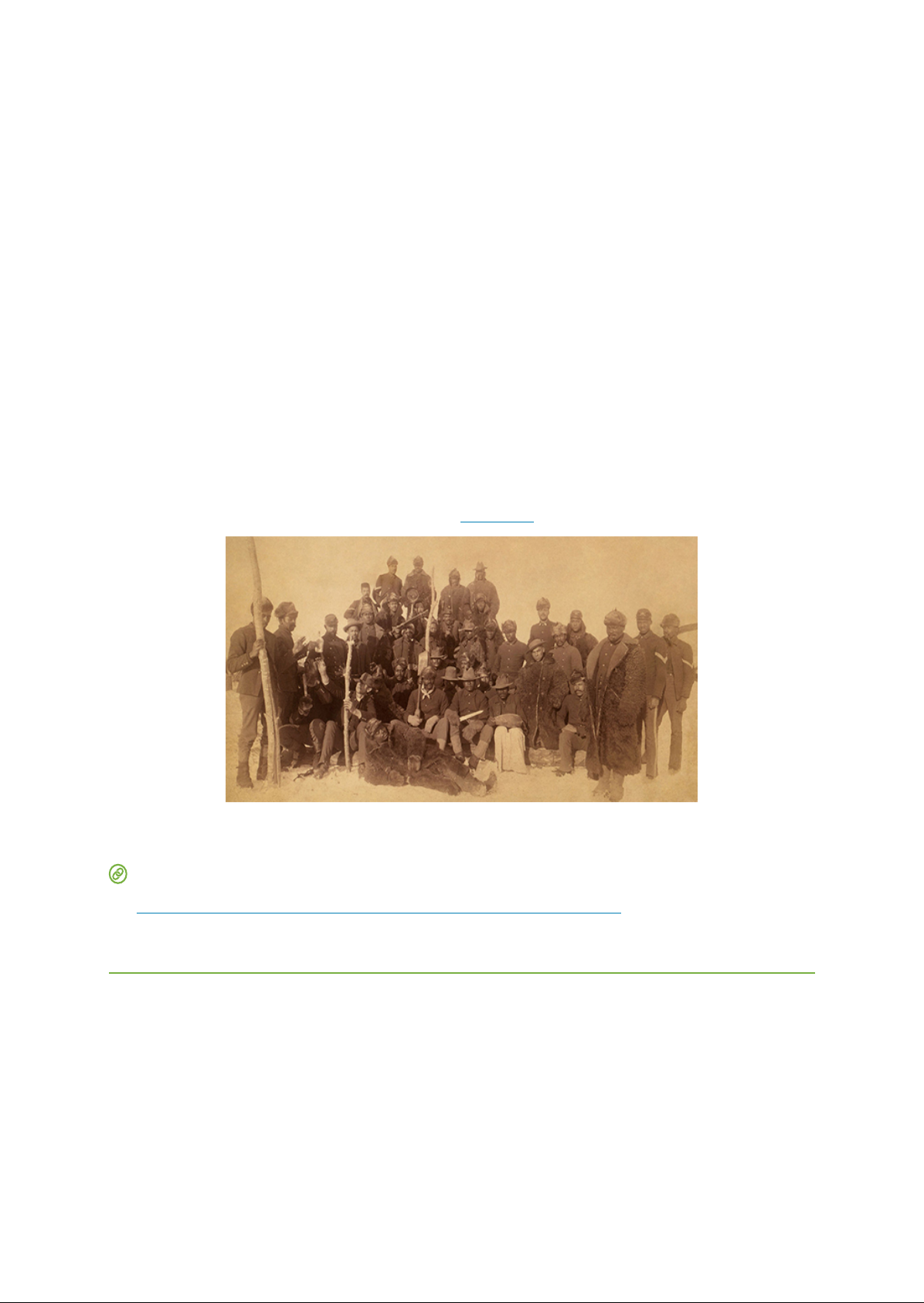

440 17 Go West Young Man ! Westward Expansion , period , the population in the United States grew from to nearly million and the population grew from to million . As they moved westward , several thousand immigrants established homesteads in the Midwest , primarily in Minnesota and Wisconsin , where , as of 1900 , over of the population was , and in North Dakota , whose immigrant population stood at 45 percent at the turn of the century . Compared to European immigrants , those from China were muc less numerous , but still . More than Chinese arrived in California between 1876 and 1890 , albeit for entirely different reasons related to the Gold Rush . In addition to a European migration westward , several thousand African Americans migra ed west following the Civil War , as much to escape the racism and violence of the Old South as to new economic opportunities . They were known as , referencing the biblical from Egypt , because they the racism of the South , with most of them headed to Kansas from Kentucky , Tennessee , Louisiana , Mississippi , and Texas . Over thousand arrived in Kansas in alone . 1890 , over Black people lived west of the Mississippi River . Although the majority of Black migrants became farmers , approximately twelve thousand worked as cowboys during the Texas cattle drives . Some also became Buffalo Soldiers in the wars against Native Americans . Buffalo Soldiers were African Americans al by various Native tribes who equated their black , curly hair with that of the buffalo . Many had served in the Union army in the Civil War and were now organized into six , cavalry and infantry uni whose primary duties were to protect settlers during the westward migration and to assist in building the infrastructure required to support western settlement Figure . FIGURE Buffalo Soldiers , the first peacetime regiments in the Army , aided settlers , fought in the Indian Wars , and served as some of the country national park rangers . CLICK AND EXPLORE The Oxford African American Studies Center ( homesteads features photographs and stories about Black homesteaders . From to settlements , the essay describes the largely hidden role that African Americans played in western expansion . While White easterners , immigrants , and African Americans were moving west , several hundred thousand Hispanics had already settled in the American Southwest prior to the government seizing the land during its war with Mexico ( The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo , which ended the war in 1848 , granted American citizenship to those who chose to stay in the United States , as the land switched from Mexican to ownership . Under the conditions of the treaty , Mexicans retained the right to their language , religion , and culture , as well as the property they held . As for citizenship , they could choose one of three options ) declare their intent to live in the United States but retain Mexican citizenship ) become citizens with all rights under the constitution or ) leave for Mexico . Despite such guarantees , within one generation , these new Hispanic American citizens found their culture under attack , and legal protection of their property all but Access for free at .

Homesteading Dreams and Realities existent . Homesteading Dreams and Realities LEARNING OBJECTIVES By the end ofthis section , you will be able to challenges that farmers faced as they settled west of the Mississippi River Describe the unique experiences of women who participated in westward migration As settlers and homesteaders moved westward to improve the land given to them through the Homestead Act , they faced a and often insurmountable challenge . The land was to farm , there were few building materials , and harsh weather , insects , and inexperience led to frequent setbacks . The prohibitive prices charged by the railroad lines made it expensive to ship crops to market or have goods sent out . Although many farms failed , some survived and grew into large bonanza farms that hired additional labor and were able to enough from economies of scale to grow . Still , small family farms , and the settlers who worked them , were to do more than scrape out a living in an unforgiving environment that comprised arid land , violent weather shifts , and other challenges Figure ) sum was ' Western um the Railroad Network FIGURE This map shows the trails ( orange ) used in westward migration and the development of railroad lines ( blue ) constructed after the completion of the transcontinental railroad . THE DIFFICULT LIFE OF THE PIONEER FARMER Of the hundreds of thousands of settlers who moved west , the vast majority were homesteaders . These pioneers , like the family of Little House on the Prairie book and television fame ( see inset below ) were seeking land and opportunity . Popularly known as sodbusters , these men and women in the Midwest faced a life on the frontier . They settled throughout the land that now makes up the Midwestern states of Wisconsin , Minnesota , Kansas , Nebraska , and the . The weather and environment were bleak , and settlers struggled to eke out a living . A few unseasonably rainy years had led settlers to believe that the great desert was no more , but the region typically low rainfall and harsh temperatures made crop cultivation hard . Irrigation was a requirement , but water and building adequate systems proved too and expensive for many farmers . It was not until 1902 and the passage of the Reclamation Act that a system existed to set aside funds from the sale of public lands to build dams for subsequent irrigation efforts . Prior to that , farmers across the Great Plains relied primarily on techniques to grow corn , wheat , and sorghum , a practice that many continued in later years . A few also began to employ windmill technology to draw water , although both the drilling and construction of windmills became an added expense that few farmers could afford . 441

442 17 Go West Young Man ! Westward Expansion , AMERICANA The Enduring Appeal of Little House on the Prairie The story of western migration and survival has remained a touchstone of American culture , even today . The television show Frontier Life on is one example , as are countless other evocations of the settlers . Consider the enormous popularity of the Little House series . The books , originally published in the and , have been in print continuously . The television show , Little House on the Prairie , ran for over a decade and was hugely successful . Despite its popularity , Little House on the Prairie has created controversy more recently for its derogatory references to the Osage people . The books , although , were based on Laura Wilder own childhood , as she travelled west with her family via covered wagon , stopping in Kansas , Wisconsin , South Dakota , and beyond ( Figure . HOUSE , on THE PRAIRIE LAU RA . a ) bi FIGURE Laura Wilder ( a ) is the celebrated author ofthe Little House series , which began in 1932 with the publication of Little House in the Big Woods . The third , and best known , book in the series , Little House on the Prairie ( was published just three years later . Wilder wrote of her stories ( As you read my stories of long ago I hope you will remember that the things that are truly worthwhile and that will give you happiness are the same now as they were then . Courage and kindness , loyalty , truth , and helpfulness are always the same and always needed . While makes the point that her stories underscore traditional values that remain the same overtime , this is not necessarily the only thing that made these books so popular . Perhaps part oftheir appeal is that they are adventure stories featuring encounters with severe weather , wild animals , and Native peoples . Does this explain their ongoing popularity ?

What other factors might make these stories appealing so long after they were originally written ?

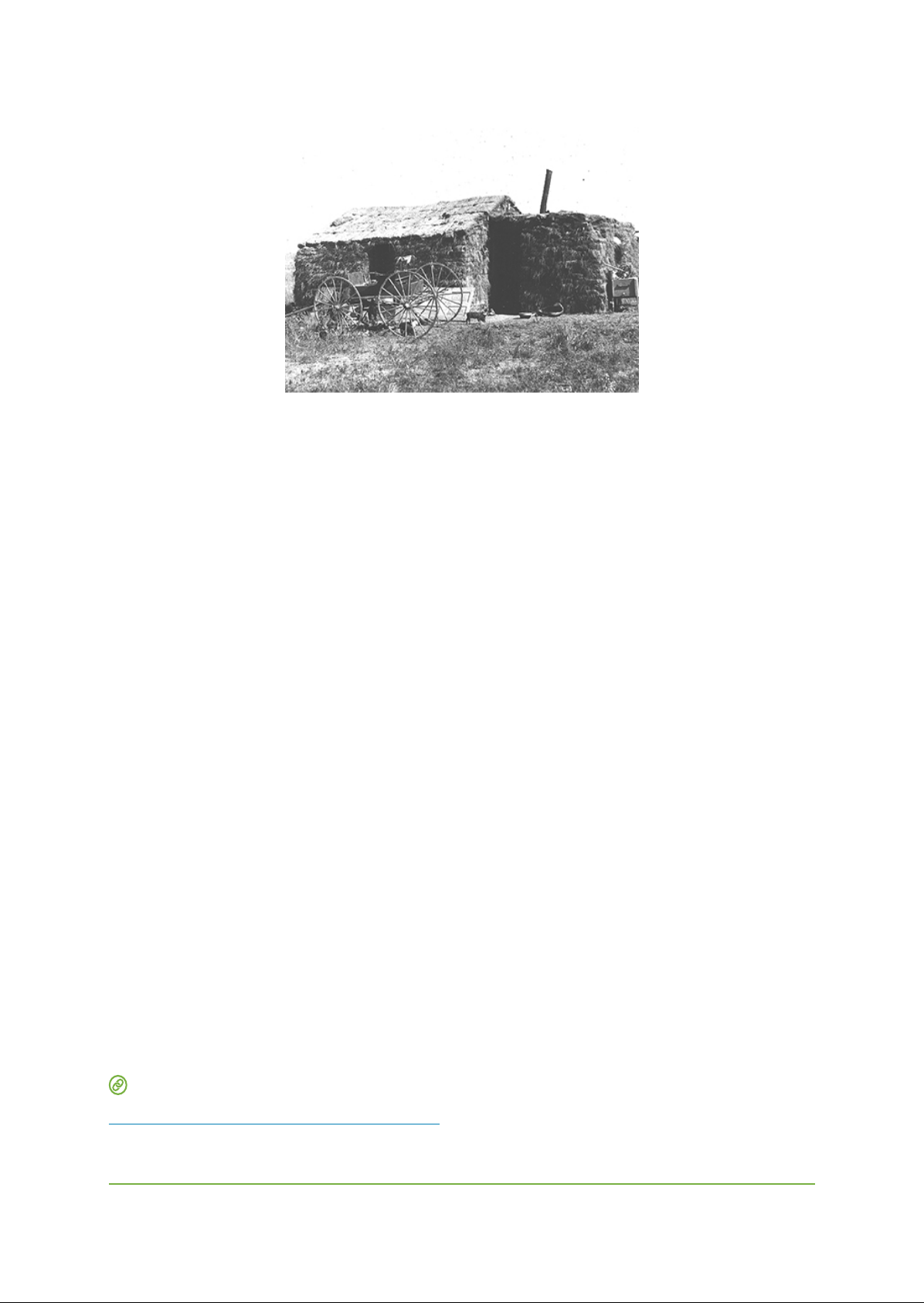

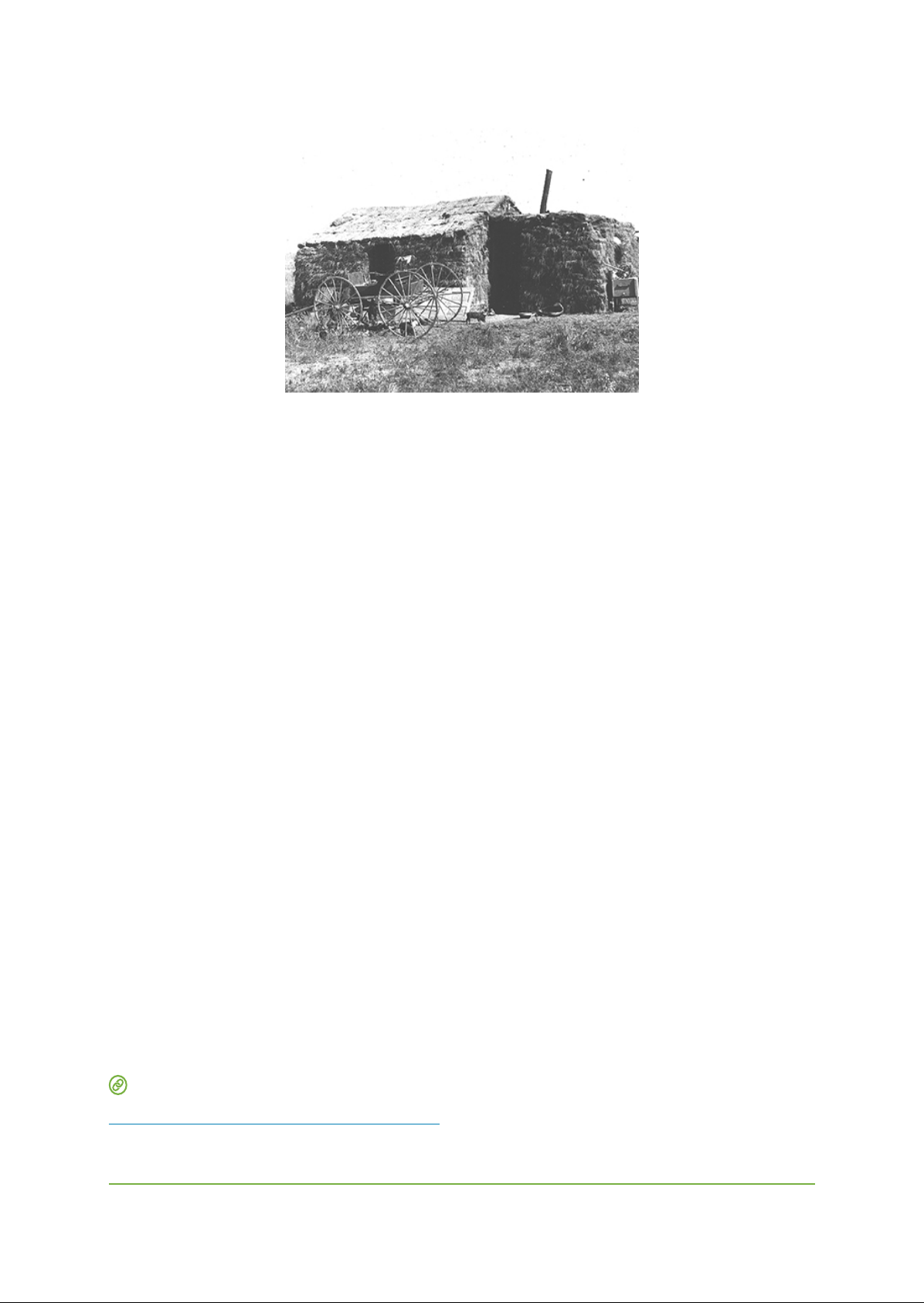

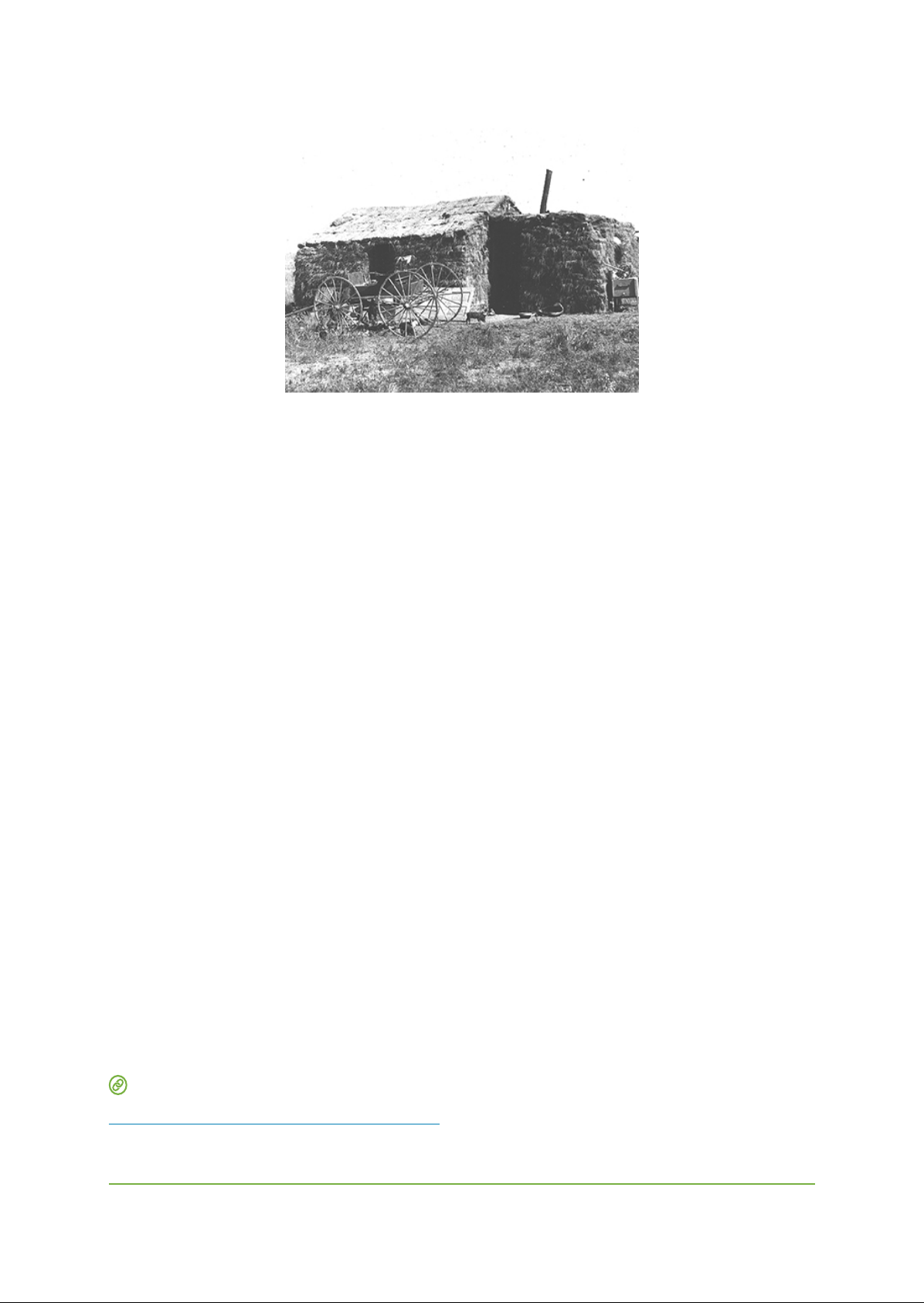

The houses built by western settlers were typically made of mud and sod with thatch roofs , as there was little timber for building . Rain , when it arrived , presented constant problems for these sod houses , with mud falling into food , and vermin , most notably lice , scampering across bedding Figure . Weather patterns not only left the dry , they also brought tornadoes , droughts , blizzards , and insect swarms . Tales of swarms of locusts were commonplace , and the insects would at times cover the ground six to twelve inches deep . One frequently quoted Kansas newspaper reported a locust swarm in 1878 during which the insects devoured everything green , stripping the foliage off the bark and from the tender twigs of the fruit Access for free at .

Homesteading Dreams and Realities 443 trees , destroying every plant that is good for food or pleasant to the eye , that man has FIGURE Sod houses were common in the Midwest as settlers moved west . There was no lumber to gather and no stones with which to build . These mud homes were vulnerable to weather and vermin , making life incredibly hard for the newly arrived homesteaders . Farmers also faced the threat of debt and farm foreclosure by the banks . While land was essentially free under the Homestead Act , all other farm necessities cost money and were initially to obtain in the newly settled parts of the country where market economies did not yet fully reach . Horses , livestock , wagons , wells , fencing , seed , and fertilizer were all critical to survival , but often hard to come by as the population initially remained sparsely settled across vast tracts of land . Railroads charged notoriously high rates for farm equipment and livestock , making it to procure goods or make a on anything sent back east . Banks also charged high interest rates , and , in a cycle that replayed itself year after year , farmers would borrow from the bank with the intention of repaying their debt after the harvest . As the number of farmers moving westward increased , the market price of their produce steadily declined , even as the value of the actual land increased . Each year , farmers produced crops , the markets and subsequently driving prices down even further . Although some understood the economics of supply and demand , none could overtly control such forces . Eventually , the arrival of a more extensive railroad network aided farmers , mostly by bringing supplies such as lumber for construction and new farm machinery . While John sold a plow as early as 1838 , it was James Oliver improvements to the device in the late that transformed life for homesteaders . His new , less expensive chilled plow was better equipped to cut through the shallow grass roots of the Midwestern terrain , as well as withstand damage from rocks just below the surface . Similar advancements in hay mowers , manure Spreaders , and threshing machines greatly improved farm production for those who could afford them . Where capital expense became a factor , larger commercial as bonanza farms to develop . Farmers in Minnesota , North Dakota , and South Dakota hired migrant farmers to grow wheat on farms in excess of twenty thousand acres each . These large farms were succeeding by the end of the century , but small family farms continued to suffer . Although the land was nearly free , it cost close to 1000 for the necessary supplies to start up a farm , and many landowners lured westward by the promise of cheap land became migrant farmers instead , working other peoples land for a wage . The frustration of small farmers grew , ultimately leading to a revolt of sorts , discussed in a later chapter . CLICK AND EXPLORE Frontier House ( includes information on the logistics of moving across the country as a homesteader . Take a look at the list of supplies and gear It is easy to understand why , even when the government gave the land away for free , it still took resources to make such a journey .

444 17 Go West Young Man ! Westward Expansion , AN EVEN MORE CHALLENGING LIFE A PIONEER WIFE Although the West was numerically a society , homesteading in particular encouraged the presence of women , families , and a domestic lifestyle , even if such a life was not an easy one . Women faced all the physical hardships that men encountered in terms of weather , illness , and danger , with the added complication of childbirth . Often , there was no doctor or midwife providing assistance , and many women died from treatable complications , as did their newborns . While some women could employment in the newly settled towns as teachers , cooks , or seamstresses , they originally did not enjoy many rights . They could not sell property , sue for divorce , serve on juries , or vote . And for the vast of women , their work was not in towns for money , but on the farm . As late as 1900 , a typical farm wife could expect to devote nine hours per day to chores such as cleaning , sewing , laundering , and preparing food . Two additional hours per day were spent cleaning the barn and chicken coop , milking the cows , caring for the chickens , and tending the family garden . One wife commented in 1879 , We are not much better than slaves . is a weary , monotonous round of cooking and washing and mending and as a result the insane asylum is a third with wives of farmers . Despite this grim image , the challenges of farm life eventually empowered women to break through some legal and social barriers . Many lived more equitably as partners with their than did their eastern counterparts , helping each other through both hard times and good . If widowed , a wife typically took over responsibility for the farm , a level of management that was very rare east , where the farm would fall to a son or other male relation . Pioneer women made important decisions and were considered by their husbands to be more equal partners in the success of the homestead , due to the necessity that all members had to work hard and contribute to the farming enterprise for it to succeed . There ore , it is not surprising that the first states to grant women rights , including the right to vote , were those in the Northwest and Upper Midwest , where women pioneers worked the land side by side with men . Some women seemed to be well suited to the challenges that frontier life presented them . Writing to her Aunt Martha from their homestead in Minnesota in 1873 , Mary Carpenter refused to complain about the hardships of farm life I try to trust in God promises , but we ca expect him to work miracles nowadays . Nevertheless , all that is expected of us is to do the best we can , and that we shall certainly endeavor to do . Even if we do freeze and starve in the way of duty , it will not be a dishonorable death . Making a Living in Gold and Cattle LEARNING OBJECTIVES By the end ofthis section , you will be able to major discoveries and developments in western gold , silver , and copper mining in the nineteenth century Explain why the cattle industry was paramount to the development ofthe West and how it became the catalyst for violent range wars Although homestead farming was the primary goal of most western settlers in the latter half of the nineteenth century , a small minority sought to make their fortunes quickly through other means . gold ( and , subsequently , silver and copper ) prospecting attracted thousands of miners looking to get rich quick before returning east . In addition , ranchers capitalized on newly available railroad lines to move longhorn steers that populated southern and western Texas . This meat was highly sought after in eastern markets , and the demand created not only wealthy ranchers but an era of cowboys and cattle drives that in many ways how we think of the West today . Although neither miners nor ranchers intended to remain permanently in the West , many individuals from both groups ultimately stayed and settled there , sometimes due to the success of their gamble , and other times due to their abject failure . THE CALIFORNIA GOLD RUSH AND BEYOND The allure of gold has long sent people on wild chases in the American West , the possibility of quick riches was no different . The search for gold represented an opportunity far different from the slow plod that Access for free at .

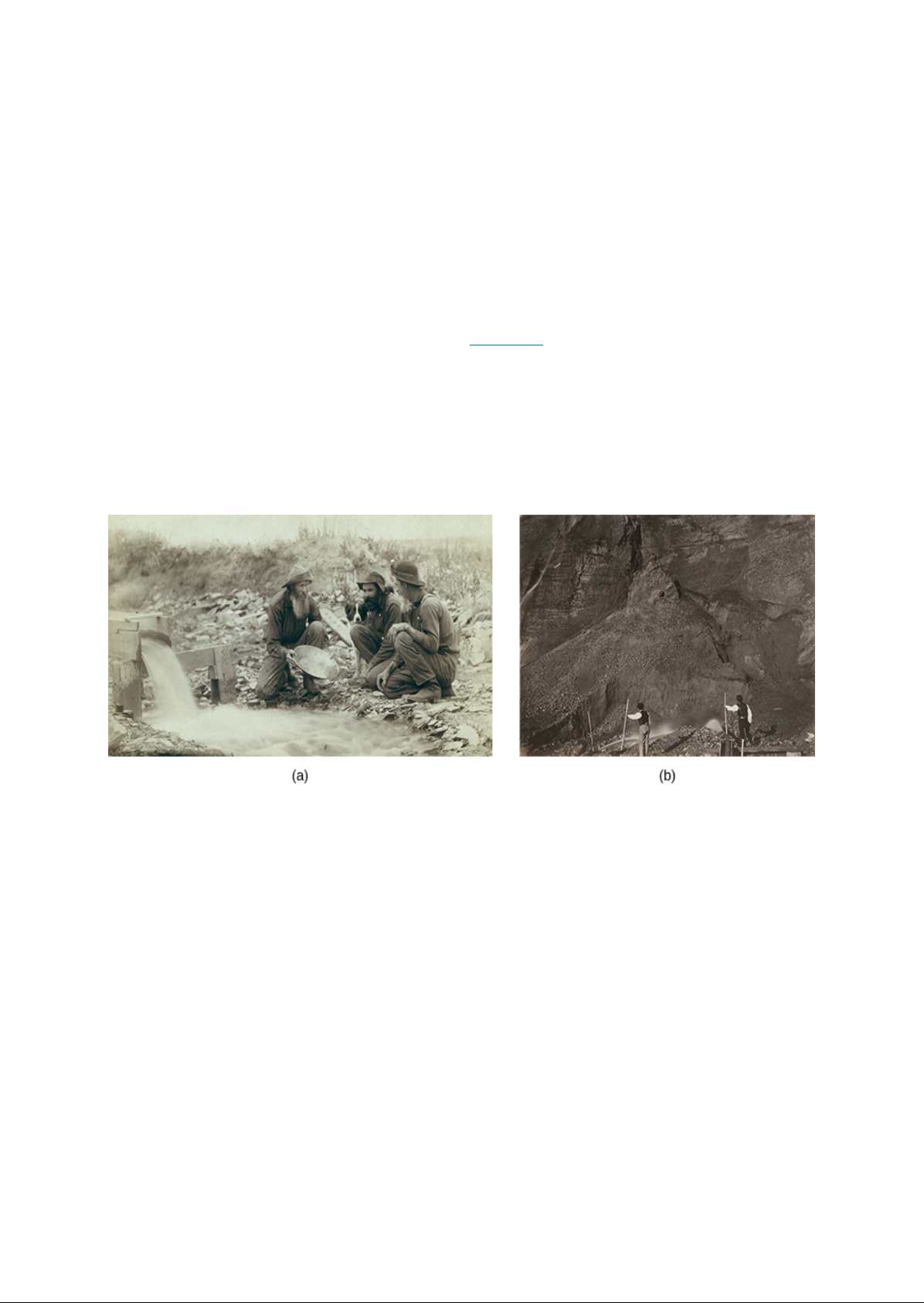

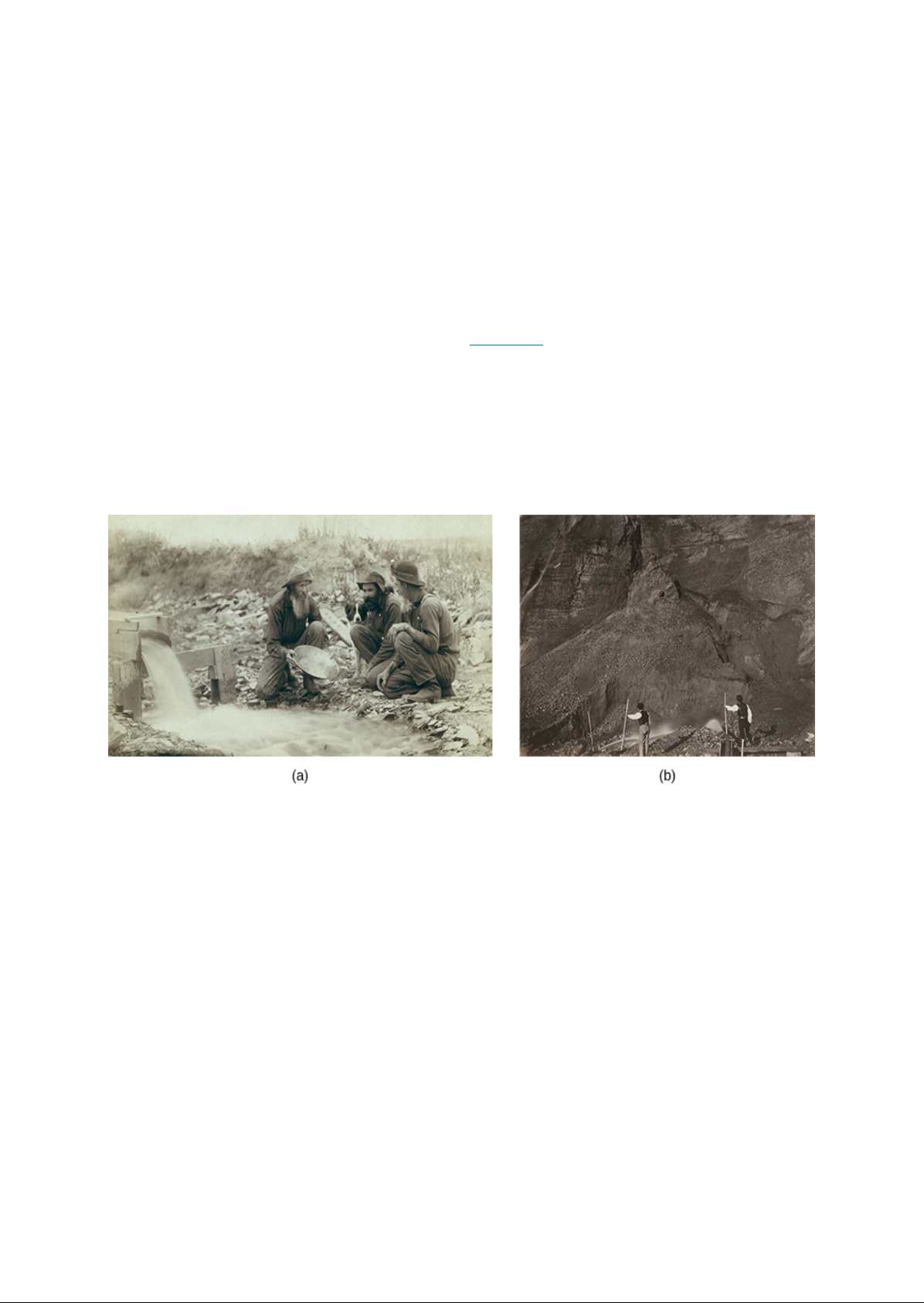

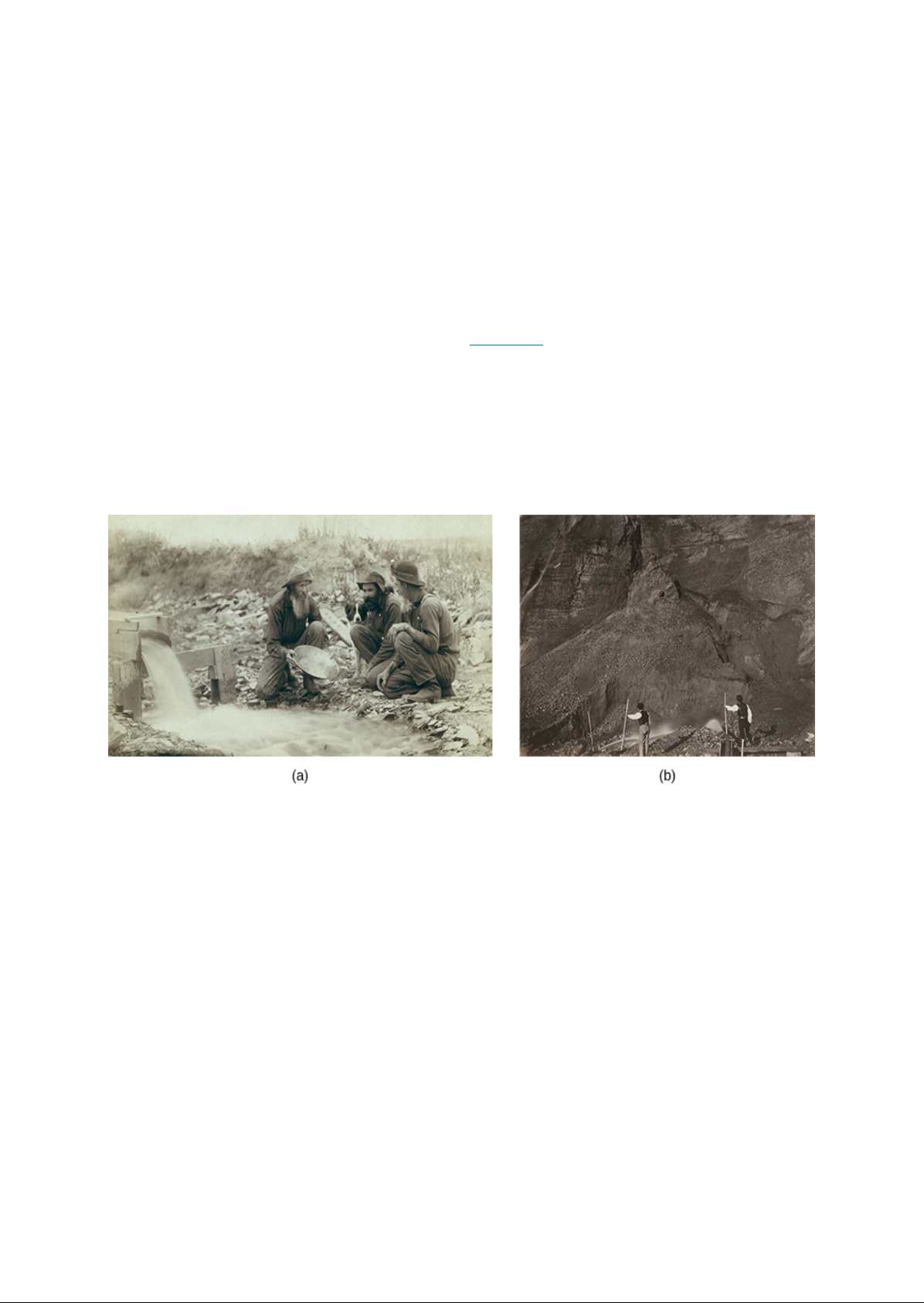

Makinga Living in Gold and Cattle 445 homesteading farmers faced . The discovery of gold at Sutter Mill in , California , set a pattern for such strikes that was repeated again and again for the next decade , in what collectively became known as the California Gold Rush . In what became typical , a sudden disorderly rush of prospectors descended upon a new discovery site , followed by the arrival of those who hoped to from the strike by preying off the newly rich . This latter group of camp followers included saloonkeepers , prostitutes , store owners , and criminals , who all arrived in droves . If the strike was in size , a town of some magnitude might establish itself , and some semblance of law and order might replace the vigilante justice that typically grew in the small and lived mining outposts . This of settlers led to a massive loss of life for Native Americans in California that some scholars view as a genocide . The original were individual prospectors who sifted gold out of the dirt and gravel through panning or by diverting a stream through a sluice box ( Figure . To varying degrees , the original California Gold Rush repeated itself throughout Colorado and Nevada for the next two decades . In 1859 , Henry , a fur trapper , began gold mining in Nevada with other prospectors but then quickly found a vein that proved to be the silver discovery in the United States . Within twenty years , the Lode , as it was called , yielded more than 300 million in shafts that reached hundreds of feet into the mountain . Subsequent mining in Arizona and Montana yielded copper , and , while it lacked the glamour of gold , these deposits created huge wealth for those who exploited them , particularly with the advent of copper wiring for the delivery of electricity and telegraph communication . FIGURE The gold prospectors in the 18505 and 18605 worked with easily portable tools that allowed anyone to follow their dream and strike it rich ( a ) It did take long for the most accessible minerals to be stripped , making way for large mining operations , including hydraulic mining , where water jets removed sediment and rocks ( By the and , however , individual efforts to locate precious metals were less successful . The hanging fruit had been picked , and now it required investment capital and machinery to dig mine shafts that could reach remaining With a much larger investment , miners needed a larger strike to be successful . This shift led to larger businesses underwriting mining operations , which eventually led to the development of greater urban stability and infrastructure . Denver , Colorado , was one of several cities that became permanent settlements , as businesses sought a stable environment to use as a base for their mining ventures . For miners who had not yet struck it rich , this development was not a good one . They were now paid a daily or weekly wage to work underground in very dangerous conditions . They worked in shafts where the temperature could rise to above one hundred degrees Fahrenheit , and where poor ventilation might lead to lung disease . They coped with shaft , dynamite explosions , and frequent . By some historical accounts , close to eight thousand miners died on the frontier during this period , with over three times that number suffering crippling injuries . Some miners organized into unions and led strikes for better conditions , but these efforts were usually crushed by state militias .

446 17 Go West Young Man ! Westward Expansion , Eventually , as the ore dried up , most mining towns turned into ghost towns . Even today , a visit through the American West shows old saloons and storefronts , abandoned as the residents moved on to their next shot at riches . The true lasting impact of the early mining efforts was the resulting desire of the government to bring law and order to the Wild West in order to more extract natural resources and encourage stable growth in the region . As more Americans moved to the region to seek permanent settlement , as opposed to brief speculative ventures , they also sought the safety and support that government order could bring . Nevada was admitted to the Union as a state in 1864 , with Colorado following in 1876 , then North Dakota , South Dakota , Montana , and Washington in 1889 and Idaho and Wyoming in 1890 . THE CATTLE KINGDOM While the cattle industry lacked the romance of the Gold Rush , the role it played in western expansion should not be underestimated . For centuries , wild cattle roamed the Spanish borderlands . At the end of the Civil War , as many as million longhorn steers could be found along the Texas frontier , yet few settlers had capitalized on the opportunity to claim them , due to the of transporting them to eastern markets . The completion of the transcontinental railroad and subsequent railroad lines changed the game dramatically . Cattle ranchers and eastern businessmen realized that it was to round up the wild steers and transport them by rail to be sold in the East for as much as thirty to dollars per head . These ranchers and businessmen began the rampant speculation in the cattle industry that made , and lost , many fortunes . So began the impressive cattle drives of the 18605 and . The famous Trail provided a quick path from Texas to railroad terminals in Abilene , Wichita , and Dodge City , Kansas , where cowboys would receive their pay . These , as they became known , quickly grew to accommodate the needs of cowboys and the cattle industry . Cattlemen like Joseph McCoy , born in Illinois , quickly realized that the railroad offered a perfect way to get highly sought beef from Texas to the East . McCoy chose Abilene as a locale that would offer cowboys a convenient place to drive the cattle , and went about building stockyards , hotels , banks , and more to support the business . He promoted his services and encouraged cowboys to bring their cattle through Abilene for good money soon , the city had grown into a bustling western city , complete with ways for the cowboys to spend their pay ( Figure 1710 . driving hardy longhorns to railroad towns that could ship the meat back east . Between 1865 and 1885 , as many as forty thousand cowboys roamed the Great Plains , hoping to work for local ranchers . They were all men , typically in their twenties , and close to of them were Hispanic or African American . It is worth noting that the stereotype of the American indeed the cowboys much from the Mexicans who had long ago settled those lands . The saddles , lassos , chaps , and that cowboy culture all arose from the Mexican ranchers who had used them to great effect before the cowboys arrived . Life as a cowboy was dirty and decidedly unglamorous . The terrain was , but the longhorn cattle were hardy stock , and could survive and thrive while grazing along the long trail , so cowboys braved the trip for the Access for free at .

Makinga Living in Gold and Cattle 447 promise of steady employment and satisfying wages . Eventually , however , the era of the free range ended . Ranchers developed the land , limiting grazing opportunities along the trail , and in 1873 , the new technology of barbed wire allowed ranchers to fence off their lands and cattle claims . With the end of the free range , the cattle industry , like the mining industry before it , grew increasingly dominated by eastern businessmen . Capital investors from the East expanded rail lines and invested in ranches , ending the reign of the cattle drives . AMERICANA Barbed Wire and a Way of Life Gone Called the devil rope by Native Americans , barbed wire had a profound impact on the American West . Before its invention , settlers and ranchers alike were stymied by a lack of building materials to fence off land . Communal grazing and long cattle drives were the norm . But with the invention of barbed wire , large cattle ranchers and their investors were able to cheaply and easily parcel off the land they or not it was legally theirs to contain . As with many other inventions , several people invented barbed wire around the same time . In 1873 , it was Joseph Glidden , however , who claimed the winning design and patented it . Not only did it spell the end ofthe free range for settlers and cowboys , it kept more land away from Native tribes ( Figure . umu . Ia mun . A ?

i ?

42 , FIGURE Joseph Glidden invention of barbed wire in 1873 made him rich , changing the face of the American West forever . credit of work by the Department of Commerce ) In the early twentieth century , songwriter Cole Porter would take a poem by a Montana poet named Bob Fletcher and convert it into a cowboy song called , Don Fence Me As the lyrics below show , the song gave voice to the feeling that , as the fences multiplied , the ethos of the West was forever changed Oh , give me land , lots of land , under starry skies above Do fence me in Let me ride thru the country that I love Do fence me in . Just turn me loose Let me straddle my old saddle underneath the western skies On my cayuse Let me wander over yonder tillI see the mountains rise

448 17 Go West Young Man ! Westward Expansion , I want to ride to the ridge where the west commences Gaze at the moon until I lose my senses I ca look at hobbles and I ca stand fences Do fence me in . VIOLENCE IN THE WILD WEST MYTH AND REALITY The popular image of the Wild West portrayed in books , television , and has been one of violence and mayhem . The lure of quick riches through mining or driving cattle meant that much of the West did indeed consist of rough men living a rough life , although the violence was exaggerated and even in the dime store novels of the day . The exploits of Wyatt Earp , Doc Holiday , and others made for good stories , but the reality was that western violence was more isolated than the stories might suggest . These clashes often occurred as people struggled for the scarce resources that could make or break their chance at riches , or as they dealt with the sudden wealth or poverty that prospecting provided . Where sporadic violence did erupt , it was concentrated largely in mining towns or during range wars among large and small cattle ranchers . Some mining towns were indeed as rough as the popular stereotype . Men , money , liquor , and disappointment were a recipe for violence . Fights were frequent , deaths were commonplace , and frontier justice reigned . The notorious mining town of Bodie , California , had murders between 1877 and 1883 , which translated to a murder rate higher than any other city at that time , and only one person was ever convicted of a crime . The most gunman of the day was John Wesley , who allegedly killed over twenty men in Texas in various , including one victim he killed in a hotel for snoring too loudly ( Figure ) FIGURE The towns that sprouted up around gold strikes existed and foremost as places for the men who struck it rich to spend their money . Stores , saloons , and brothels were among the first businesses to arrive . The combination of lawlessness , vice , and money often made for a dangerous mix . Ranching brought with it its own dangers and violence . In the Texas cattle lands , owners of large ranches took advantage of their wealth and the new invention of barbed wire to claim the prime grazing lands and few watering holes for their herds . Those seeking only to move their few head of cattle to market grew increasingly frustrated at their inability to even a blade of grass for their meager herds . Eventually , frustration turned to violence , as several ranchers resorted to vandalizing the barbed wire fences to gain access to grass and water for their steers . Such vandalism quickly led to cattle rustling , as these cowboys were not averse to leading a few of the rancher steers into their own herds as they left . One example of the violence that bubbled up was the infamous Fence Cutting War in Clay County , Texas Access for free at .

The Assault on American Indian Life and Culture 449 ( There , cowboys began destroying fences that several ranchers erected along public lands land they had no right to enclose . Confrontations between the cowboys and armed guards hired by the ranchers resulted in three a war , but enough of a problem to get the governor attention . Eventually , a special session of the Texas legislature addressed the problem by passing laws to outlaw fence cutting , but also forced ranchers to remove fences illegally erected along public lands , as well as to place gates for passage where public areas adjoined private lands . An even more violent confrontation occurred between large ranchers and small farmers in Johnson County , Wyoming , where cattle ranchers organized a lynching bee in to make examples of cattle rustlers . invaders from Texas to serve as hired guns , the ranch owners and their foremen hunted and subsequently killed the two rustlers best known for organizing the owners of the smaller Wyoming farms . Only the intervention of federal troops , who arrested and then later released the invaders , allowing them to return to Texas , prevented a greater massacre . While there is much real and the rough men who lived this life , relatively few women experienced it . While homesteaders were often families , gold speculators and cowboys tended to be single men in pursuit of fortune . The few women who went to these wild outposts were typically prostitutes , and even their numbers were limited . In 1860 , in the Lode region of Nevada , for example , there were reportedly only thirty women total in a town of hundred men . Some of the painted ladies who began as prostitutes eventually owned brothels and emerged as businesswomen in their own right however , life for these young women remained a challenging one as western settlement progressed . A handful of women , numbering no more than six hundred , braved both the elements and culture to become teachers in several of the more established cities in the West . Even fewer arrived to support husbands or operate stores in these mining towns . As wealthy men brought their families west , the lawless landscape began to change slowly . Abilene , Kansas , is one example of a lawless town , replete with prostitutes , gambling , and other vices , transformed when class women arrived in the with their cattle baron husbands . These women began to organize churches , school , civic clubs , and other community programs to promote family values . They fought to remove opportunities for prostitution and all the other vices that they felt threatened the values that they held dear . Protestant missionaries eventually joined the women in their efforts , and , while they were not widely successful , they did bring greater attention to the problems . As a response , the Congress passed both the Law ( named after its chief proponent , crusader Anthony ) in 1873 to ban the spread of lewd and lascivious literature through the mail and the subsequent Page Act of 1875 to prohibit the transportation of women into the United States for employment as prostitutes . However , the houses of ill repute continued to operate and remained popular throughout the West despite the efforts of reformers . CLICK AND EXPLORE Take a look at the National and Western Heritage Museum ( to determine whether this site portrayal of cowboy culture matches or contradicts the history shared in this chapter . The Assault on American Indian Life and Culture LEARNING OBJECTIVES By the end ofthis section , you will be able to Describe the methods that the government used to address the Indian problem during the settlement of the West Explain the United States policy of as it applied to Native peoples in the nineteenth century As American settlers pushed westward , they inevitably came into with Native tribes that had long been living on the land . Although the threat of attacks was quite slim and nowhere proportionate to the number of

450 17 Go West Young Man ! Westward Expansion , Army actions directed against them , the occasional one of enough to fuel popular fear of Native peoples . The clashes , when they happened , were indeed brutal , although most of the brutality occurred at the hands of the settlers . Ultimately , the settlers , with the support of local militias and , later , with the federal government behind them , sought to eliminate the tribes from the lands they desired . This effort ultimately succeeded despite some Native military victories , and fundamentally changed the American Indian way of life . CLAIMING LAND , RELOCATING LANDOWNERS Back east , the popular vision of the West was ofa vast and empty land . But of course this was an inaccurate depiction . On the eve of westward expansion , as many as Native Americans , representing a variety of tribes , populated the Great Plains . Previous wars against tribes in the East in the early nineteenth century , as well as the failure of earlier treaties , led to a general policy of removal of these tribes west of the Mississippi . The Indian Removal Act of 1830 resulted in multiple forced removals , including the infamous Trail of Tears , which saw nearly thousand Cherokee , Seminole , Choctaw , and Creek people relocated to what is now Oklahoma between 1831 and 1838 . Building upon such a , the government was prepared , during the era of western settlement , to deal with tribes that settlers viewed as obstacles to expansion . As settlers sought more land for farming , mining , and cattle , the first strategy employed to deal with the perceived Indian problem was to negotiate treaties to move tribes out of the path of White settlers . In 1851 , the chiefs of most of the Great Plains tribes agreed to the First Treaty of Fort Laramie . This agreement established distinct tribal borders , essentially codifying the reservation system . In return for annual payments of to the tribes ( originally guaranteed for years , but ater revised to last for only ten ) as well as the hollow promise of noninterference from westward settlers , the participating tribes agreed to stay clear of the path of settlement . Due to government corruption , many annuity payments never reached the tribes , and some reservations were left destitute and near starving . In addition , wi hin a decade , as the pace and number of western settlers increased , even designated reservations became prime locations for farms and mining . Rather than waiting for new treaties , backed local or state militia attacked the tribes out of fear or to force them from the land . Some American Indians resisted , only to then ace massacres . In 1862 , frustrated and angered by the lack of annuity payments , increasing hunger among their people , and he continuous encroachment on their reservation lands , in Minnesota rebelled in what became nown as the Dakota War or the War of 1862 , killing the White settlers who moved onto their tribal lands . Over one thousand White settlers were captured or killed in the attack , before an armed militia regained control . Of he four hundred Sioux captured by troops , 303 were sentenced to death , but President Lincoln intervened , releasing all but of the men . Lincoln government hanged the remaining Dakota men in the largest mass execution in the country history . The government imprisoned other Dakota in the uprising , and banished their families from Minnesota . Settlers in other regions responded news of this raid with fear and aggression . In Colorado , and Cheyenne tribes fought back against and encroachment White militias then formed , decimating even some of the tribes that were willing to cooperate . One of the more vicious examples was near Sand Creek , Colorado , where Colonel John ed a militia raid upon a camp in which the Cheyenne leader Black Kettle had already negotiated a peaceful settlement . The camp was both the American and the white of surrender when murdered close to one hundred people , the majority of them women and children , and mutilated the in what became known as the Sand Creek Massacre . For the rest of his life , would proudly display his collection of nearly one hundred Native American scalps from that day . Subsequent investigations the Army condemned tactics and their results however , the raid served as a model for some settlers who sought any means by which to eradicate the perceived Indian threat . The incident growing disagreement between Americans in the eastern and western parts of the nation about best to handle Indian affairs . Access for free at .

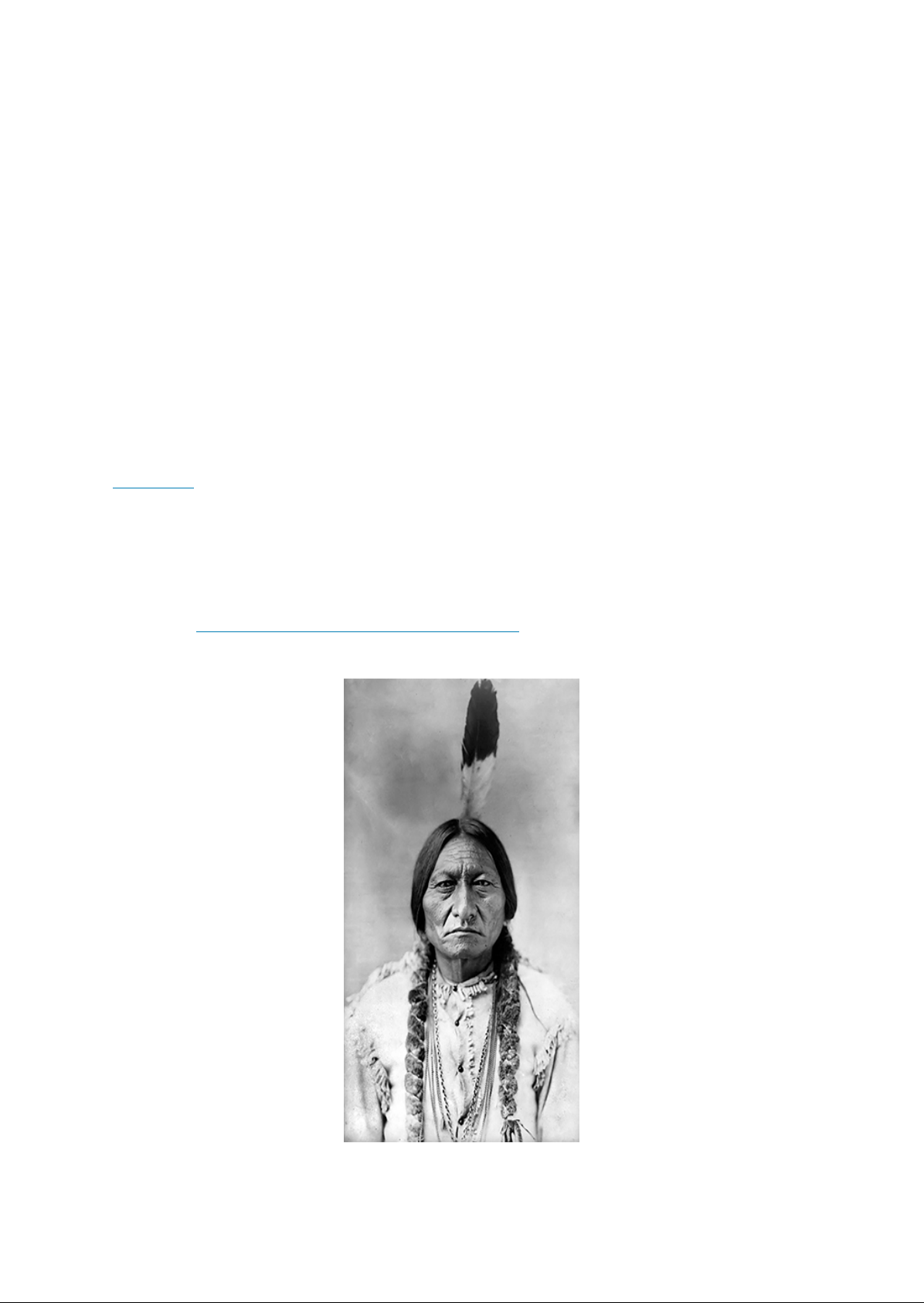

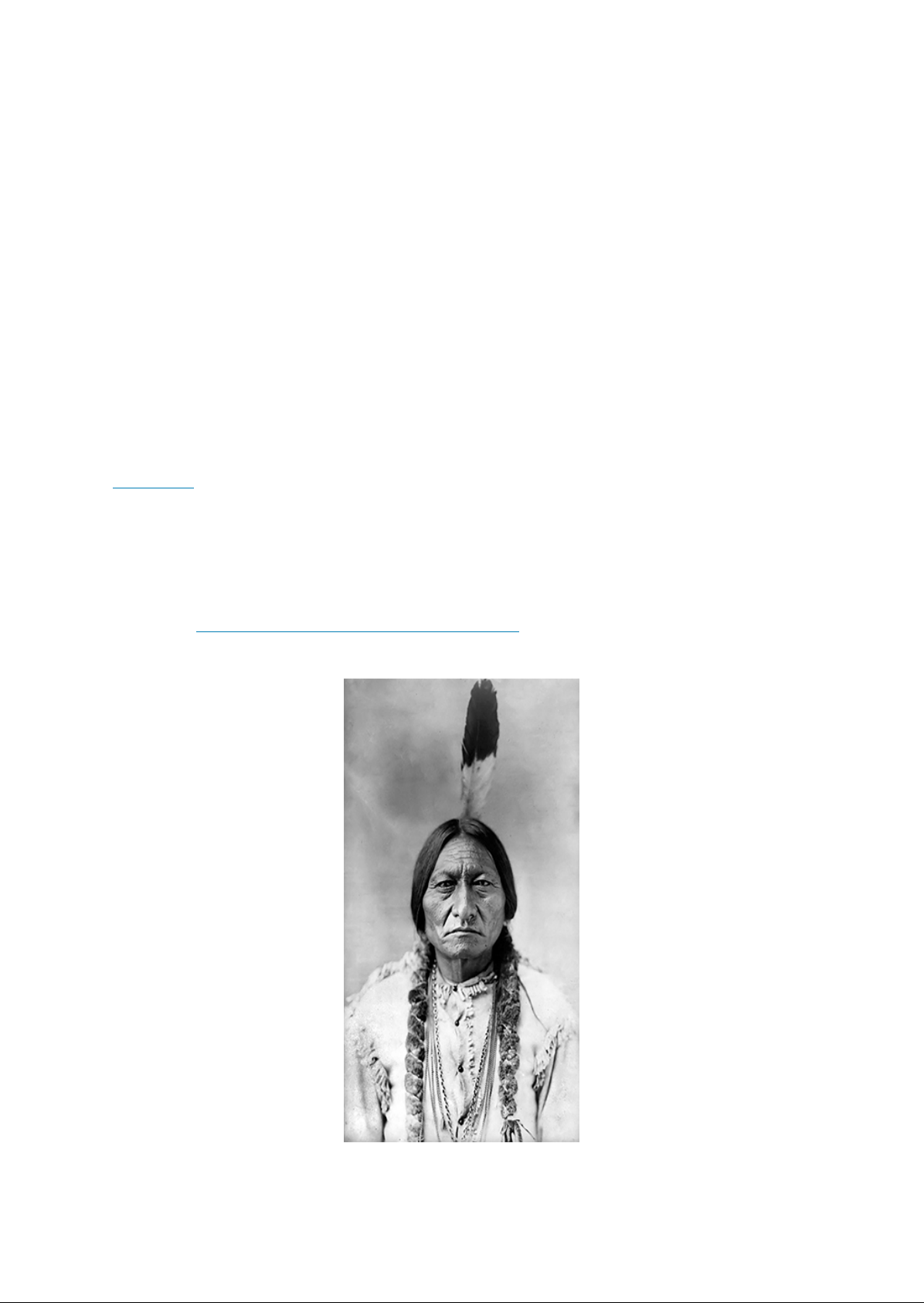

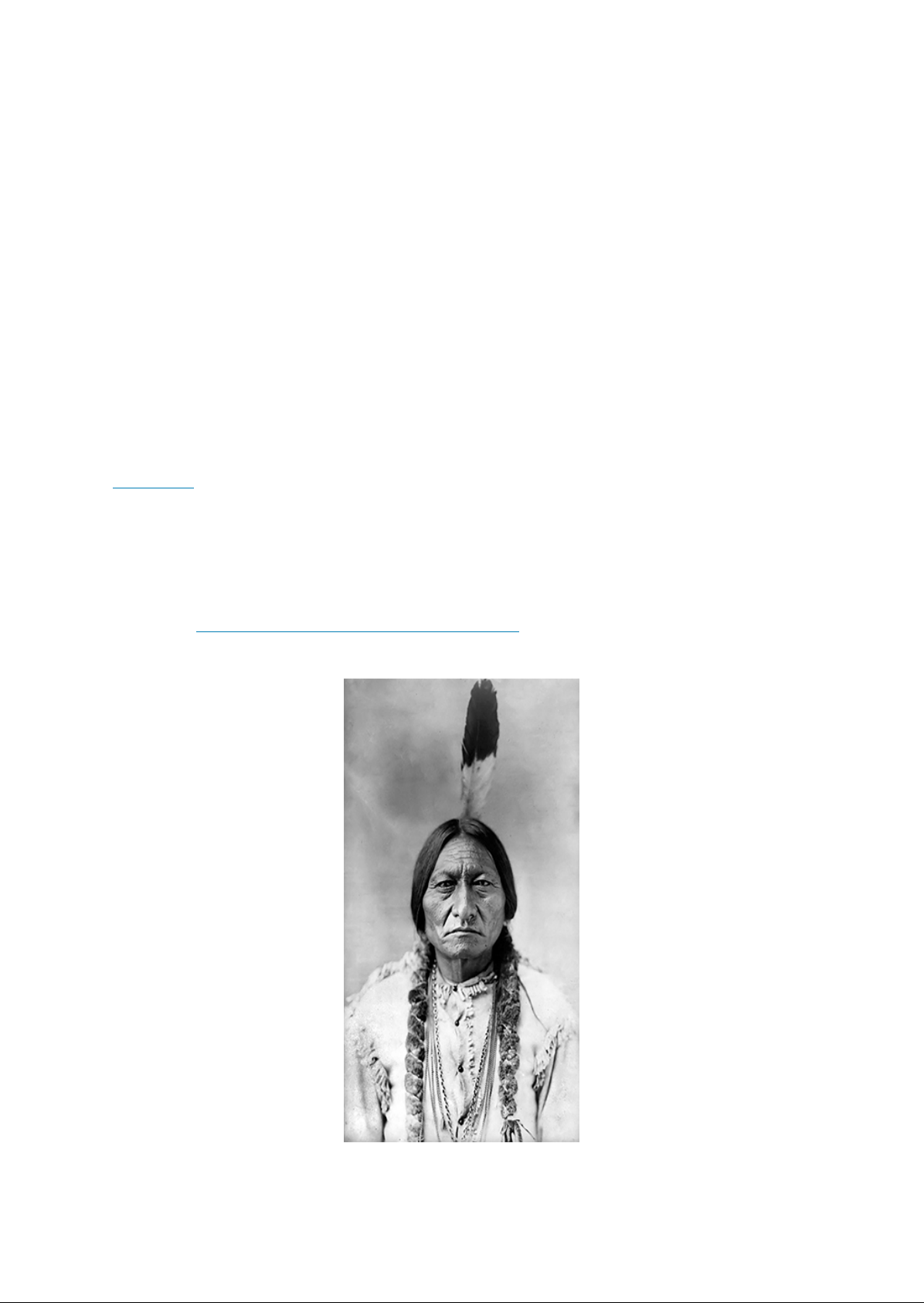

The Assault on American Indian Life and Culture 451 Hoping to forestall similar uprisings and wars , the Congress commissioned a committee to investigate the causes of such incidents . The subsequent report of their led to the passage of two additional treaties the Second Treaty of Fort Laramie and the Treaty of Medicine Lodge Creek , both designed to move the remaining tribes to even more remote reservations . The Second Treaty of Fort Laramie moved the remaining Lakota people to the Black Hills in the Dakota Territory and the Treaty of Medicine Lodge Creek moved the Cheyenne , and Comanche people to Indian Territory , later to become the State of Oklahoma . The agreements were , however . With the subsequent discovery of gold in the Black Hills , settlers seeking their fortune began to move upon the newly granted Sioux lands with support from cavalry troops . By the middle of 1875 , thousands of White prospectors were illegally digging and panning in the area . The Lakota people protested the invasion of their territory and the violation of sacred ground . The government offered to lease the Black Hills or to pay million if the Indians were willing to sell the land . When the tribes refused , the government imposed what it considered a fair price for the land , ordered the Indians to move , and in the spring of 1876 , made ready to force them onto the reservation . In the Battle of Little Bighorn , perhaps the most famous battle of the American West , a Lakota chief , Sitting Bull , urged Native Americans from all neighboring tribes to join his men in defense of their lands Figure . At the Little Bighorn River , the Army Seventh Cavalry , led by Colonel George Custer , sought a showdown . Driven by his own personal ambition , on June 25 , 1876 , Custer foolishly attacked what he thought was a minor encampment . Instead , it turned out to be a large group of , Cheyennes , and . The three thousand in and killed Custer and 262 of his men and support units , in the single greatest loss of troops to a Native American force in the era of westward expansion . Look at these winter counts ( by Lakota Horse at the National Museum of Natural History to explore a Lakota perspective on westward expansion . i A ' ill FIGURE The iconic Sitting Bull led Lakota , Cheyenne , and warriors in what was the largest victory against American troops during Westward expansion . While the Battle of the Little Big Horn was a rout by the

452 17 Go West Young Man ! Westward Expansion , and their allies over Custer troops , Native American resistance in the American West ultimately failed to halt American expansion . AMERICAN INDIAN SUBMISSION Despite their success at Little Bighorn , neither the Lakota people nor any other Plains tribes followed this battle with any other armed encounter . Rather , they either returned to tribal life or out of fear of remaining troops , until the Army arrived in greater numbers and began to exterminate Indian encampments and force others to accept payment for forcible removal from their lands . Sitting Bull himself to Canada , although he later returned in 1881 and subsequently worked in Buffalo Bill Wild West show . In Montana , the Blackfoot and Crow were forced to leave their tribal lands . In Colorado , the Utes gave up their lands after a brief period of resistance . In Idaho , most of the Nez Perce gave up their lands peacefully , although in an incredible episode , a band of some eight hundred Indians sought to evade troops and escape into Canada . MY STORY I Will Fight No More Chief Joseph Capitulation Chief Joseph , known to his people as Thunder the Loftier Mountain Heights , was the chief of the Nez Perce tribe , and he had realized that they could not win against the White people . In order to avoid a would undoubtedly lead to the extermination of his people , he hoped to lead his tribe to Canada , where they could live freely . He led a full retreat of his people over hundred miles of mountains and harsh terrain , only to be caught within miles of the Canadian border in late 1877 . His speech has remained a poignant and vivid reminder of what the tribe had lost . Tell General Howard I know his heart . What he told me before , I have it in my heart . I am tired of . Our Chiefs are killed Looking Glass is dead , Ta Hool Hool is dead . The old men are all dead . It is the young men who say yes or no . He who led on the young men is dead . It is cold , and we have no blankets the little children are death . My people , some of them , have run away to the hills , and have no blankets , no food . No one knows where they freezing to death . I want to have time to look for my children , and see how many of them I can . Maybe I shall them dead . Hear me , my Chiefs ! I am tired my heart is sick and sad . From where the sun now stands I will no more Joseph , 1877 The episode in the Indian Wars occurred in 1890 , at the Wounded Knee Massacre in South Dakota . On their reservation , the Lakota people had begun to perform the Ghost Dance , which told of a Messiah who would deliver the tribe from its hardship , with such frequency that White settlers began to worry that another uprising would occur . The Calvary prepared to round up the people performing the Ghost Dance . Frightened after the death of Sitting Bull at the hands of tribal police , a group of Lakota Ghost Dancers led by Bigfoot . When the Cavalry caught up to them at Wounded Knee , South Dakota on December 29 , 1890 , the prepared to surrender . Although the accounts are unclear , an apparent accidental discharge by a young Lakota man preparing to lay down his weapon led the soldiers to begin indiscriminately upon the Native Americans . What little resistance the mounted with a handful of concealed at the outset of the diminished quickly , with the troops eventually massacring between 150 and 300 men , women , and children . The troops suffered fatalities , some of which were the result of their own . Captain Edward Godfrey of the Seventh Cavalry later commented , I know the men did not aim deliberately and they were greatly excited . I do believe they saw their sights . They rapidly but it seemed to me only a few seconds till there was not a living thing before us warriors , squaws , children , ponies , and dogs . went down before that unaimed fire . The United States awarded twenty of these soldiers the Congressional Medal of Honor , the nation highest military honor . With this last show of brutality , the Indian Wars came to a close . government had already begun the process of seeking an Access for free at .

The Assault on American Indian Life and Culture 453 alternative to the meaningless treaties and costly battles . A more effective means with which to address the public perception of the Indian problem was needed . provided the answer . hrough the years of the Indian Wars of the and early , opinion back east was mixed . There were many who felt , as General Philip Sheridan ( appointed in 1867 to pacify the Plains Indians ) allegedly said , that the only good Indian was a dead Indian . But increasingly , several American reformers who would later form he backbone of the Progressive Era had begun to criticize the violence , arguing that the government should the Native Americans through an policy aimed at assimilating them into American society . Individual land ownership , Christian worship , and education for children became the cornerstones of his new assault on Native life and culture . Beginning in the 18803 , clergymen , government , and social workers all worked to assimilate Native into American life . The government helped reformers remove Native American children from their and the cultural of their families and place them in boarding schools , such as the Carlisle Indian School , where they were forced to abandon their tribal traditions and embrace social and cultural practices . Such schools Native American boys and girls and provided vocational raining for males and domestic science classes for females . Boarding schools sought to convince Native children to abandon their language , clothing , and social customs for a more lifestyle ( Figure ) FIGURE The federal government policy towards Native Americans shifted in the late from the reservation system to into the American ideal . A vital part of the assimilation effort was land reform . During earlier negotiations , the government had recognized Native American communal ownership of land . Although many tribes recognized individual families use rights to plots of land , the tribe owned the land . As a part of their plan to the tribes , reformers sought legislation to replace this concept with the popular notion of real estate ownership and . One such law was the Dawes Severalty Act of 1887 , named after a reformer and senator from Massachusetts . In what was essentially a new version of the original Homestead Act , the Dawes Act permitted the federal government to divide the lands of any tribe and grant 160 acres of farmland or 320 acres of grazing land to each head of family , with lesser amounts to single persons and others . In a nod towards the paternal relationship with which White people viewed Native to the of the previous treatment of enslaved African Dawes Act permitted the federal government to hold an individual Native Americans newly acquired land in trust for years . Only then would they obtain full title and be granted the citizenship rights that land ownership entailed . It would not be until 1924 that formal citizenship was granted to all Native Americans . Under the Dawes Act , Native Americans were assigned the most arid , useless land and surplus land went to White settlers . The government sold as much as eighty million acres of Native American land to White American settlers .

454 17 Go West Young Man ! Westward Expansion , CLICK AND EXPLORE Take a look at the Carlisle Industrial Indian School ( which attempted to assimilate Native American students from 1879 to 1918 . Look through the photographs and records of the school to assess the school impact on the student cultural practices . The Impact of Expansion on Chinese Immigrants and Hispanic Citizens LEARNING OBJECTIVES By the end ofthis section , you will be able to Describe the treatment of Chinese immigrants and Hispanic citizens duringthe westward expansion ofthe nineteenth century As White Americans pushed west , they not only collided with Native American tribes but also with Hispanic Americans and Chinese immigrants . Hispanics in the Southwest had the opportunity to become American citizens at the end of the war , but their status was markedly . Chinese immigrants arrived en masse during the California Gold Rush and numbered in the hundreds of thousands by the late , with the majority living in California , working menial jobs . These distinct cultural and ethnic groups strove to maintain their rights and way of life in the face of persistent racism and entitlement . But the large number of White settlers and land acquisitions left them at a profound disadvantage . Ultimately , both groups withdrew into homogenous communities in which their language and culture could survive . CHINESE IMMIGRANTS IN THE AMERICAN WEST The initial arrival of Chinese immigrants to the United States began as a slow trickle in the 18205 , with barely 650 living in the by the end of 1849 . However , as gold rush fever swept the country , Chinese immigrants , too , were attracted to the notion of quick fortunes . By 1852 , over Chinese immigrants had arrived , and by 1880 , over Chinese lived in the United States , most in California . While they had dreams of gold , many instead found employment building the transcontinental railroad ( Figure 1715 ) Some even traveled as far east as the former cotton plantations of the Old South , which they helped to farm after the Civil War . Several thousand of these immigrants booked their passage to the United States using a , in which their passage was paid in advance by American businessmen to whom the immigrants were then indebted for a period of work . Most arrivals were men Few wives or children ever traveled to the United States . As late as 1890 , less than percent of the Chinese population in the was female . Regardless of gender , few Chinese immigrants intended to stay permanently in the United States , although many were reluctantly forced to do so , as they lacked the resources to return home . Access for free at .

The Impact of Expansion on Chinese Immigrants and Hispanic Citizens 455 FIGURE Building the railroads was dangerous and backbreaking work . On the western railroad line , Chinese migrants , along with other workers , were often given the most and dangerous jobs of all . Prohibited by law since 1790 from obtaining citizenship through naturalization , Chinese immigrants faced harsh discrimination and violence from American settlers in the West . Despite hardships like the special tax that Chinese miners had to pay to take part in the Gold Rush , or their subsequent forced relocation into Chinese districts , these immigrants continued to arrive in the United States seeking a better life for the families they left behind . Only when the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 forbade further immigration from China for a period did the stop . The Chinese community banded together in an effort to create social and cultural centers in cities such as San Francisco . In a haphazard fashion , they sought to provide services ranging from social aid to education , places of worship , health facilities , and more to their fellow Chinese immigrants . As Chinese workers began competing with White Americans for jobs in California cities , the latter began a system of discrimination . In the , White Americans formed clubs ( coolie being a racial slur directed towards people of any Asian descent ) through which they organized boycotts of products and lobbied for laws . Some protests turned violent , as in 1885 in Rock Springs , Wyoming , where tensions between White and Chinese immigrant miners erupted in a riot , resulting in over two dozen Chinese immigrants being murdered and many more injured . Slowly , racism and discrimination became law . The new California constitution of 1879 denied naturalized Chinese citizens the right to vote or hold state employment . Additionally , in 1882 , the Congress passed the Chinese Exclusion Act , which forbade further Chinese immigration into the United States for ten years . The ban was later extended on multiple occasions until its repeal in 1943 . Eventually , some Chinese immigrants returned to China . Those who remained were stuck in the , most menial jobs . Several found assistance through the creation of benevolent associations designed to both support Chinese communities and defend them against political and legal discrimination however , the history of Chinese immigrants to the United States remained largely one of deprivation and hardship well into the twentieth century . CLICK AND EXPLORE The Central Railroad Photographic History Museum ( provides a context for the role of the Chinese who helped build the railroads . What does the site celebrate , and what , if anything , does it condemn ?

456 17 Go West Young Man ! Westward Expansion , DEFINING AMERICAN The Backs that Built the Railroad Below is a description ofthe construction ofthe railroad in 1867 . Note the way it describes the scene , the laborers , and the effort . The cars now ( 1867 ) run nearly to the summit of the Sierras . four thousand laborers were at tenth Irish , the rest Chinese . They were a great army laying siege to Nature in her strongest citadel . The rugged mountains looked like stupendous . They swarmed with Celestials , shoveling , wheeling , carting , drilling and blasting rocks and earth , while their dull , moony eyes stared out from under immense , like umbrellas . At several dining camps we saw hundreds sitting on the ground , eating soft boiled rice with chopsticks as fast as terrestrials could with . Irish laborers received thirty dollars per month ( gold ) and board Chinese , dollars , boarding themselves . After a little experience the latter were quite as efficient and far less Richardson , Beyond the Mississippi Several great American advancements of the nineteenth century were built with the hands of many other nations . It is ponder how much these immigrant communities felt they were building their own fortunes and futures , versus the fortunes of others . 15 it likely that the Chinese laborers , many of whom died due to the harsh conditions , considered themselves part of a great army ?

Certainly , this account reveals the unwitting racism of the day , where workers were grouped together by their ethnicity , and each ethnic group was labeled as good workers or troublesome , with no regard for individual differences among the hundreds of Chinese or Irish workers . HISPANIC AMERICANS IN THE AMERICAN WEST The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo , which ended the War in 1848 , promised citizenship to the nearly thousand Hispanics now living in the American Southwest approximately 90 percent accepted the offer and chose to stay in the United States despite their immediate relegation to class citizenship status . Relative to the rest of Mexico , these lands were sparsely populated and had been so ever since the country achieved its freedom from Spain in 1821 . In fact , New Texas or the center of settlement in the region in the years immediately preceding the war with the United States , containing nearly thousand Mexicans . However , those who did settle the area were proud of their heritage and ability to develop rancheros of great size and success . Despite promises made in the treaty , these they came to be lost their land to White settlers who simply displaced the rightful landowners , by force if necessary . Repeated efforts at legal redress mostly fell upon deaf ears . In some instances , judges and lawyers would permit the legal cases to proceed through an expensive legal process only to the point where Hispanic landowners who insisted on holding their ground were rendered penniless for their efforts . Much like Chinese immigrants , Hispanic citizens were relegated to the jobs under the most terrible working conditions . They worked as ( manual laborers similar to enslaved people ) Vaqueros ( cattle herders ) and ( transporting food and supplies ) on the cattle ranches that White landowners possessed , or undertook the most hazardous mining tasks ( Figure . Access for free at .

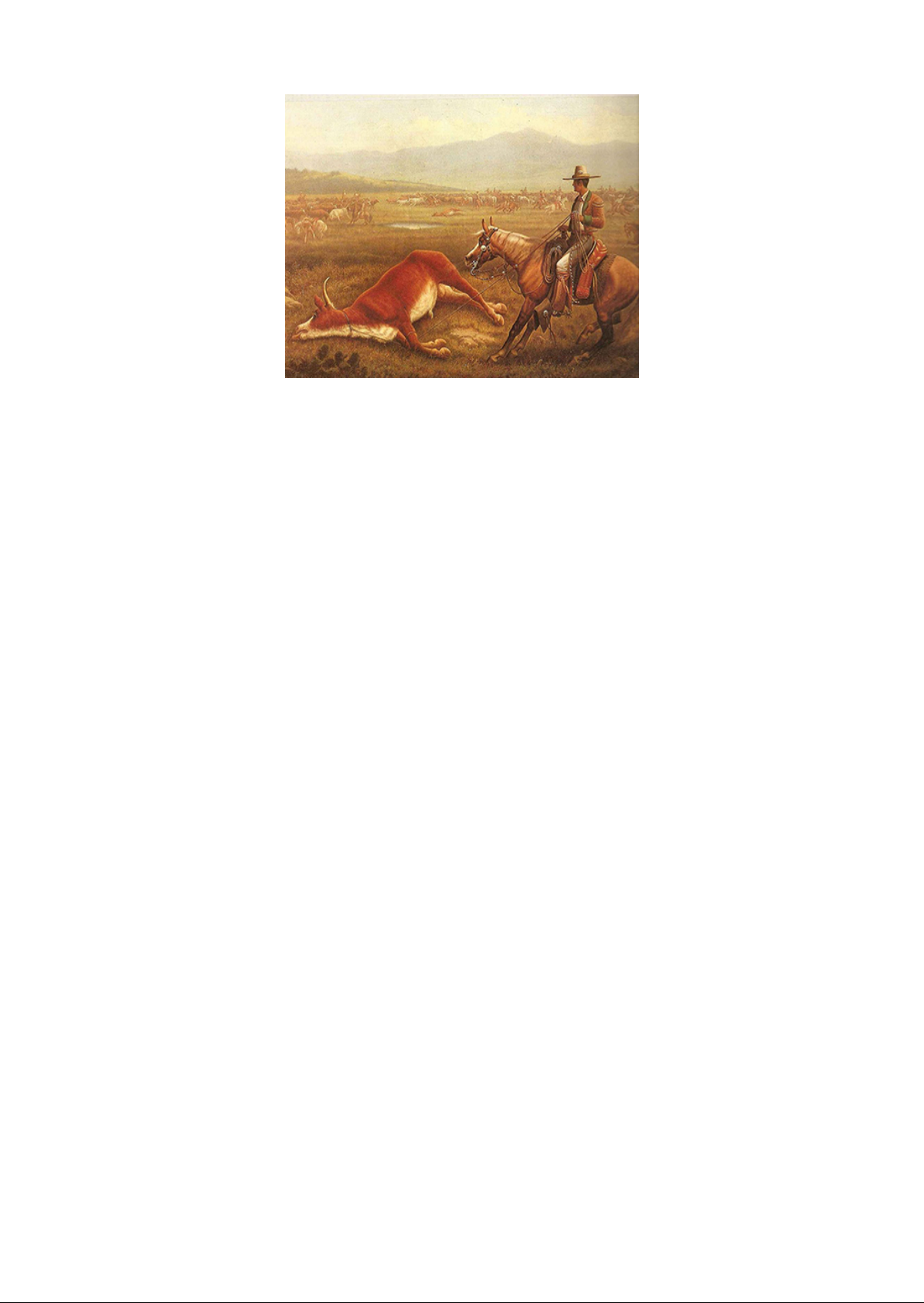

The Impact of Expansion on Chinese Immigrants and Hispanic Citizens 457 FIGURE Mexican ranchers had worked the land in the American Southwest long before American cowboys arrived . In what ways might the Mexican vaquero pictured above have influenced the American cowboy ?

In a few instances , frustrated Hispanic citizens fought back against the White settlers who dispossessed them of their belongings . In in New Mexico , several hundred Mexican Americans formed ( the White Caps ) to try and reclaim their land and intimidate White Americans , preventing further land seizures . White Caps conducted raids of White farms , burning homes , barns , and crops to express their growing anger and frustration . However , their actions never resulted in any fundamental changes . Several White Caps were captured , beaten , and imprisoned , whereas others eventually gave up , fearing harsh reprisals against their families . Some White Caps adopted a more political strategy , gaining election to local throughout New Mexico in the early , but growing concerns over the potential impact upon the quest for statehood led several citizens to heighten their repression of the movement . Other laws passed in the United States intended to deprive Mexican Americans of their heritage as much as their lands . Sunday Laws prohibited noisy amusements such as , and other cultural gatherings common to Hispanic communities at the time . Greaser Laws permitted the imprisonment of any unemployed Mexican American on charges of vagrancy . Although Hispanic Americans held tightly to their cultural heritage as their remaining form of , such laws did take a toll . In California and throughout the Southwest , the massive of settlers simply overran the Hispanic populations that had been living and thriving there , sometimes for generations . Despite being citizens with full rights , Hispanics quickly found themselves outnumbered , outvoted , and , ultimately , outcast . Corrupt state and local governments favored White people in land disputes , and mining companies and cattle barons discriminated against them , as with the Chinese workers , in terms of pay and working conditions . In growing urban areas such as Los Angeles , barrios , or clusters of homes , grew more isolated from the White American centers . Hispanic Americans , like the Native Americans and Chinese , suffered the fallout of the White settlers relentless push west .

458 17 Key Terms Key Terms the policy aimed at assimilating Native Americans into a middle class , Protestant version of the American way of life through boarding schools for Native American children and land allotment for Native American households bonanza farms large farms owned by speculators who hired laborers to work the land these large farms allowed their owners to from economies of scale and prosper , but they did nothing to help small family farms , which continued to struggle California Gold Rush the period between 1848 and 1849 when prospectors found large strikes of gold in California , leading others to rush in and follow suit this period led to a cycle and bust through the area , as gold was discovered , mined , and stripped Lode the silver in the country , discovered by Henry in 1859 in Nevada a term used to describe African Americans who moved to Kansas from the Old South to escape the racism there Fence Cutting War this armed between cowboys moving cattle along the trail and ranchers who wished to keep the best grazing lands for themselves occurred in Clay County , Texas , between 1883 and 1884 las the Spanish name for White Caps , the rebel group of Hispanic Americans who fought back against the appropriation of Hispanic land by White people for a period in , they burned farms , homes , and crops to express their growing anger at the injustice of the situation Manifest Destiny the phrase , coined by journalist John Sullivan , which came to stand for the idea that White Americans had a calling and a duty to seize and settle the American West with Protestant democratic values Sand Creek Massacre a militia raid led by Colonel on a Cheyenne and peoples camp in Colorado , both the American and the white of surrender over one hundred men , women , and children were killed sod house a frontier home constructed of dirt held together by prairie grass that was prevalent in the Midwest sod , cut into large rectangles , was stacked to make the walls of the structure , providing an inexpensive , yet damp , house for western settlers Wounded Knee Massacre an attempt to disarm a group of Lakota people near Wounded Knee , South Dakota , which resulted in members of the Seventh Cavalry of the Army opening and killing over 150 Lakota Summary The Westward Spirit While a few bold settlers had moved westward before the middle of the nineteenth century , they were the exception , not the rule . The great American desert , as it was called , was considered a vast and empty place , for civilized people . In the 18405 , however , this idea started to change , as potential settlers began to learn more from promoters and land developers of the economic opportunities that awaited them in the West , and Americans extolled the belief that it was their Manifest divine explore and settle the western territories in the name of the United States . Most settlers in this wave were White Americans of means . Whether they sought riches in gold , cattle , or farming , or believed it their duty to spread Protestant ideals to native inhabitants , they headed west in wagon trains along paths such as the Oregon Trail . European immigrants , particularly those from Northern Europe , also made the trip , settling in ethnic enclaves out of comfort , necessity , and familiarity . African Americans escaping the racism of the South also went west . In all , the newly settled areas were neither a fast track to riches nor a simple expansion into an empty land , but rather a clash of cultures , races , and traditions that the emerging new America . Access for free at .