Early Globalization_ The Atlantic World, 1492–1650

Explore the Early Globalization_ The Atlantic World, 1492–1650 study material pdf and utilize it for learning all the covered concepts as it always helps in improving the conceptual knowledge.

Early Globalization_ The Atlantic World, 1492–1650 PDF Download

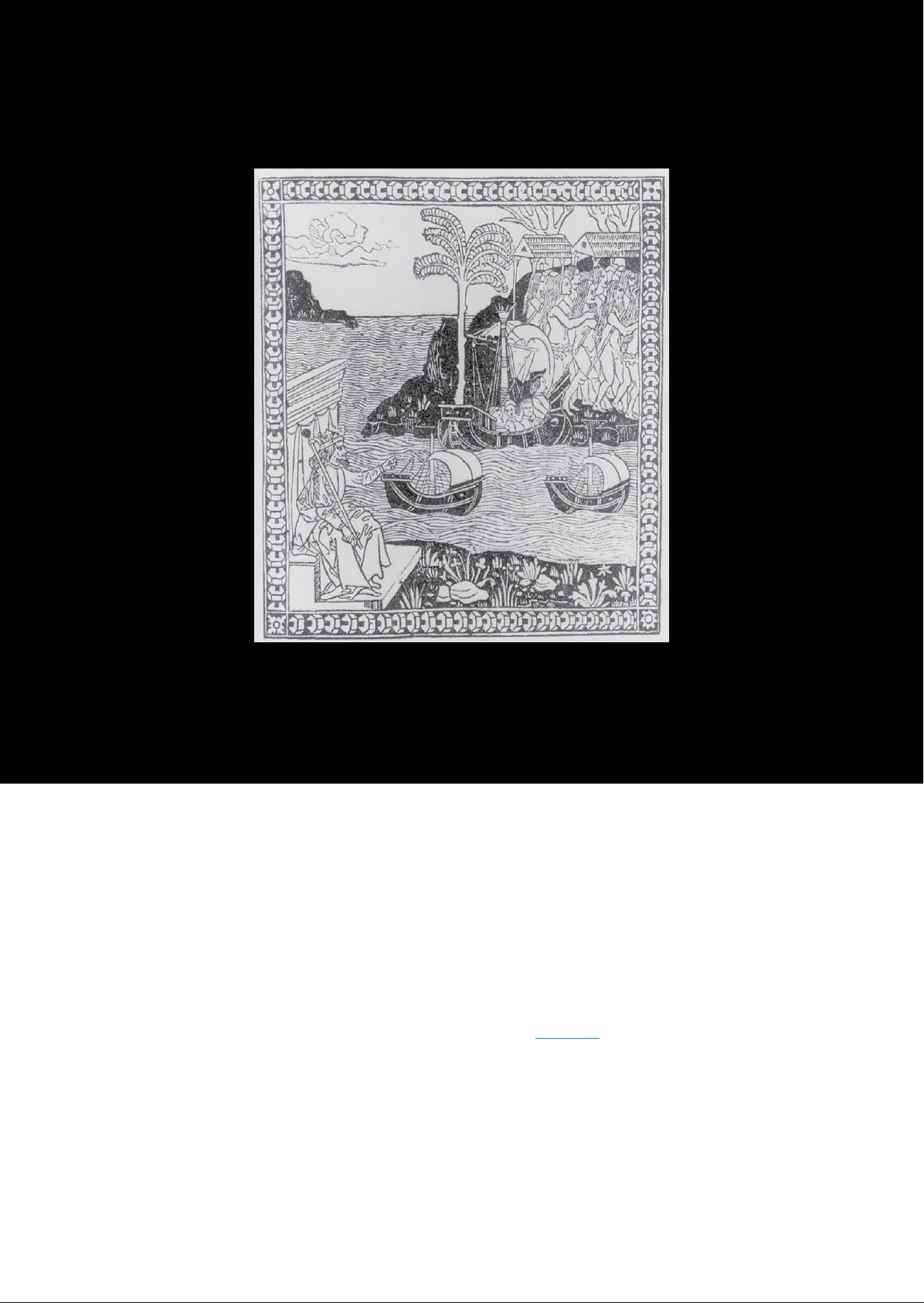

Early Globalization The Atlantic World , was . FIGURE After Christopher Columbus discovered the New World , he sent letters home to Spain wonders he beheld . These letters were quickly circulated throughout Europe and translated into Italian , German , and Latin , This woodcut is from the Italian verse translation of the letter Columbus sent to the Spanish court after his voyage , delle by Giuliano . CHAPTER OUTLINE Portuguese Exploration and Spanish Conquest Religious Upheavals in the Developing Atlantic World Challenges to Spain Supremacy New Worlds in the Americas Labor , Commerce , and the Columbian Exchange INTRODUCTION The story of the Atlantic World is the story of global migration , a migration driven in large part by the actions and aspirations of the ruling heads of Europe . Columbus is hardly visible in this illustration of his ships making landfall on the Caribbean island of ) Instead , Ferdinand II of Spain ( in the foreground ) sits on his throne and points toward Columbus landing . As the ships arrive , the people tower over the Spanish , suggesting the native population density of the islands . This historic moment in 1492 sparked new rivalries among European powers as they scrambled to create New World colonies , fueled by the quest for wealth and power as well as by religious passions . Almost continuous war resulted . Spain achieved early preeminence , creating a empire and growing rich with treasures from the Americas . Native Americans who confronted the newcomers from Europe suffered unprecedented

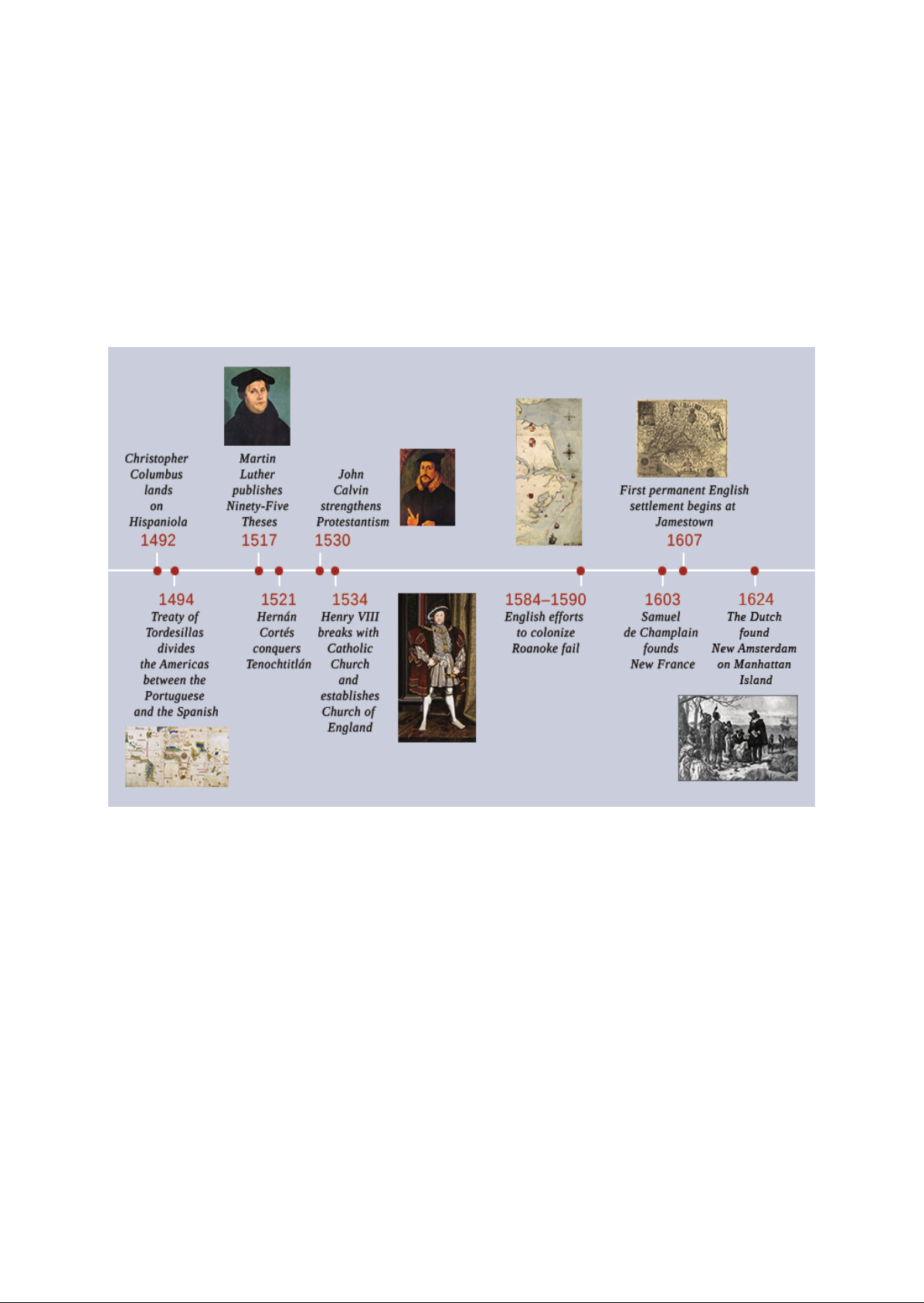

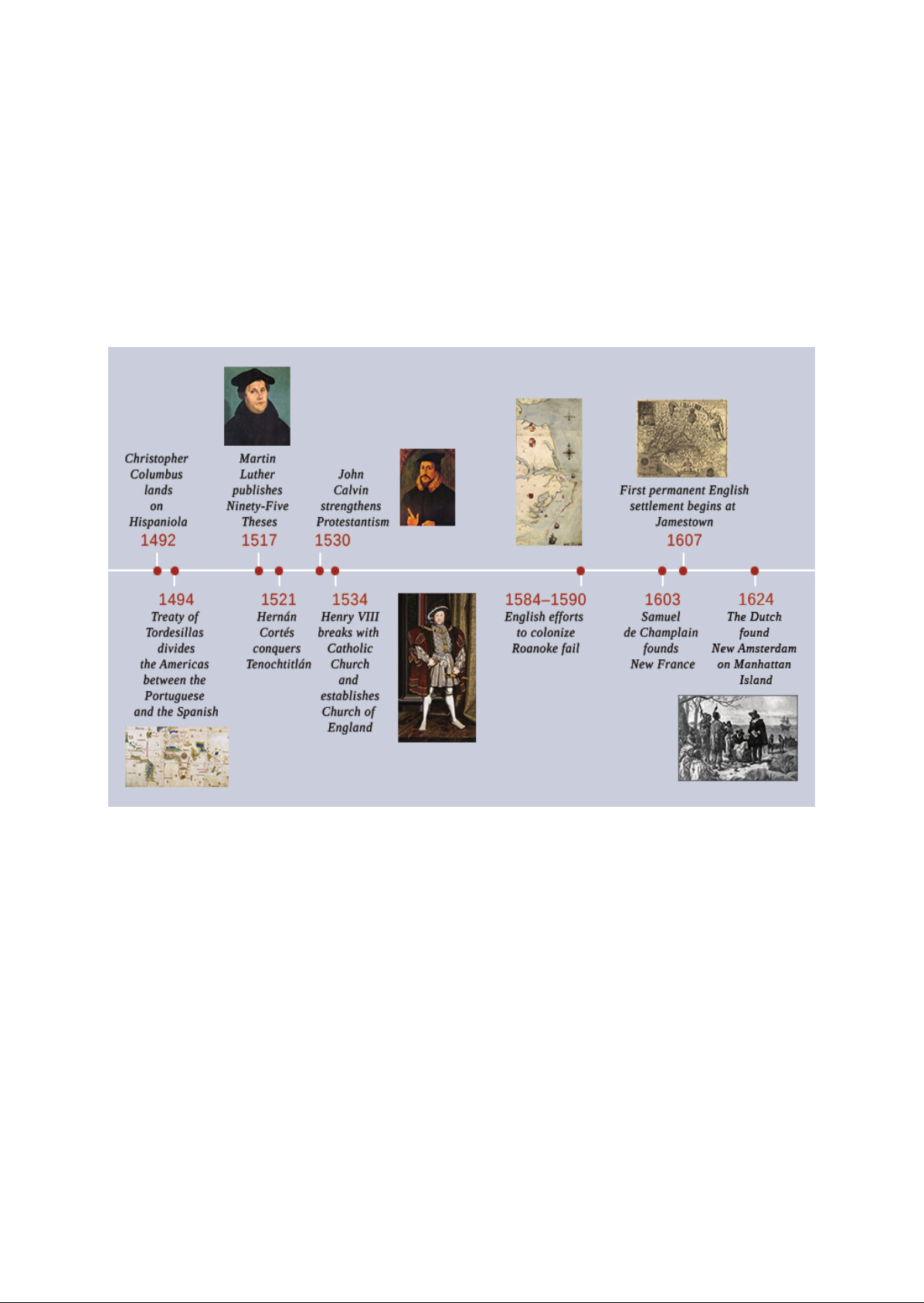

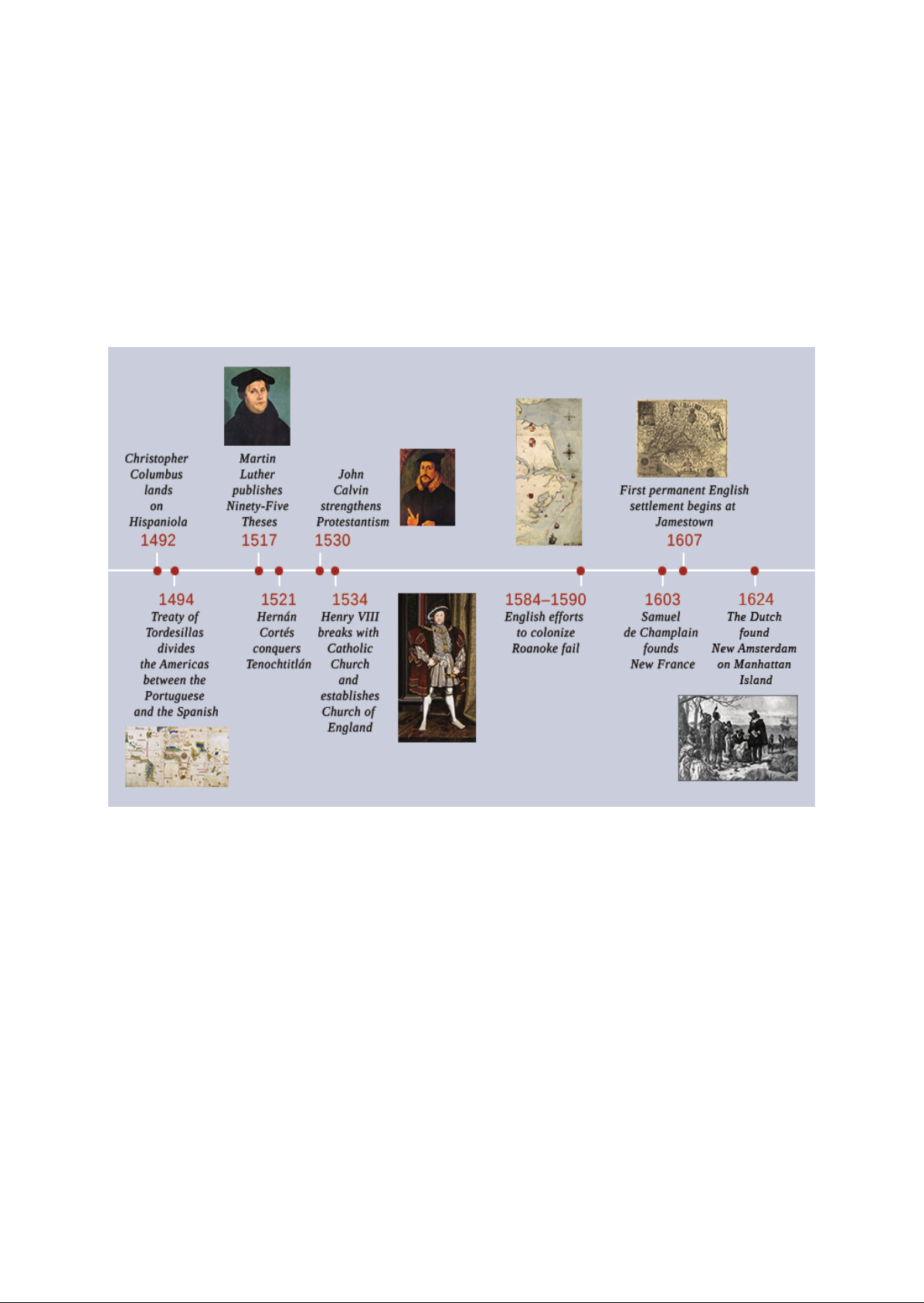

32 Early Globalization The Atlantic World , losses of life , however , as previously unknown diseases sliced through their populations . They also were victims of the arrogance of the Europeans , who viewed themselves as uncontested masters of the New World , sent by God to bring Christianity to the Portuguese Exploration and Spanish Conquest LEARNING OBJECTIVES By the end ofthis section , you will be able to Describe Portuguese exploration of the Atlantic and Spanish exploration ofthe Americas , and the importance of these voyages to the developing Atlantic World Explain the importance of Spanish exploration of the Americas in the expansion of Spain empire and the development of Spanish Renaissance culture Christopher Martin Columbus Luther John A lands publishes Calvin First permanent English on strengthens settlement begins at Theses Protestantism Jamestown 1492 1517 1530 1607 1494 1521 1534 1603 1624 Theory of Henry English efforts Samuel The Dutch Cortes breaks with to colonize de found divides conquers Catholic Roanoke fail founds New Amsterdam the Americas Church New France on Manhattan between the and Island Portuguese establishes and the Spanish Church of . England FIGURE Portuguese colonization of Atlantic islands in the inaugurated an era of aggressive European expansion across the Atlantic . In the , Spain surpassed Portugal as the dominant European power . This age of exploration and the subsequent creation of an Atlantic World marked the earliest phase of globalization , in which previously isolated , Native Americans , and came into contact with each other , sometimes with disastrous results . PORTUGUESE EXPLORATION Portugal Prince Henry the Navigator spearheaded his country exploration of Africa and the Atlantic in the . With his support , Portuguese mariners successfully navigated an eastward route to Africa , establishing a foothold there that became a foundation of their nation trade empire in the and sixteenth centuries . Portuguese mariners built an Atlantic empire by colonizing the Canary , Cape Verde , and Azores Islands , as well as the island of Madeira . Merchants then used these Atlantic outposts as debarkation points for subsequent journeys . From these strategic points , Portugal spread its empire down the western coast of Africa to the Congo , along the western coast of India , and eventually to Brazil on the eastern coast of South America . It also Access for free at .

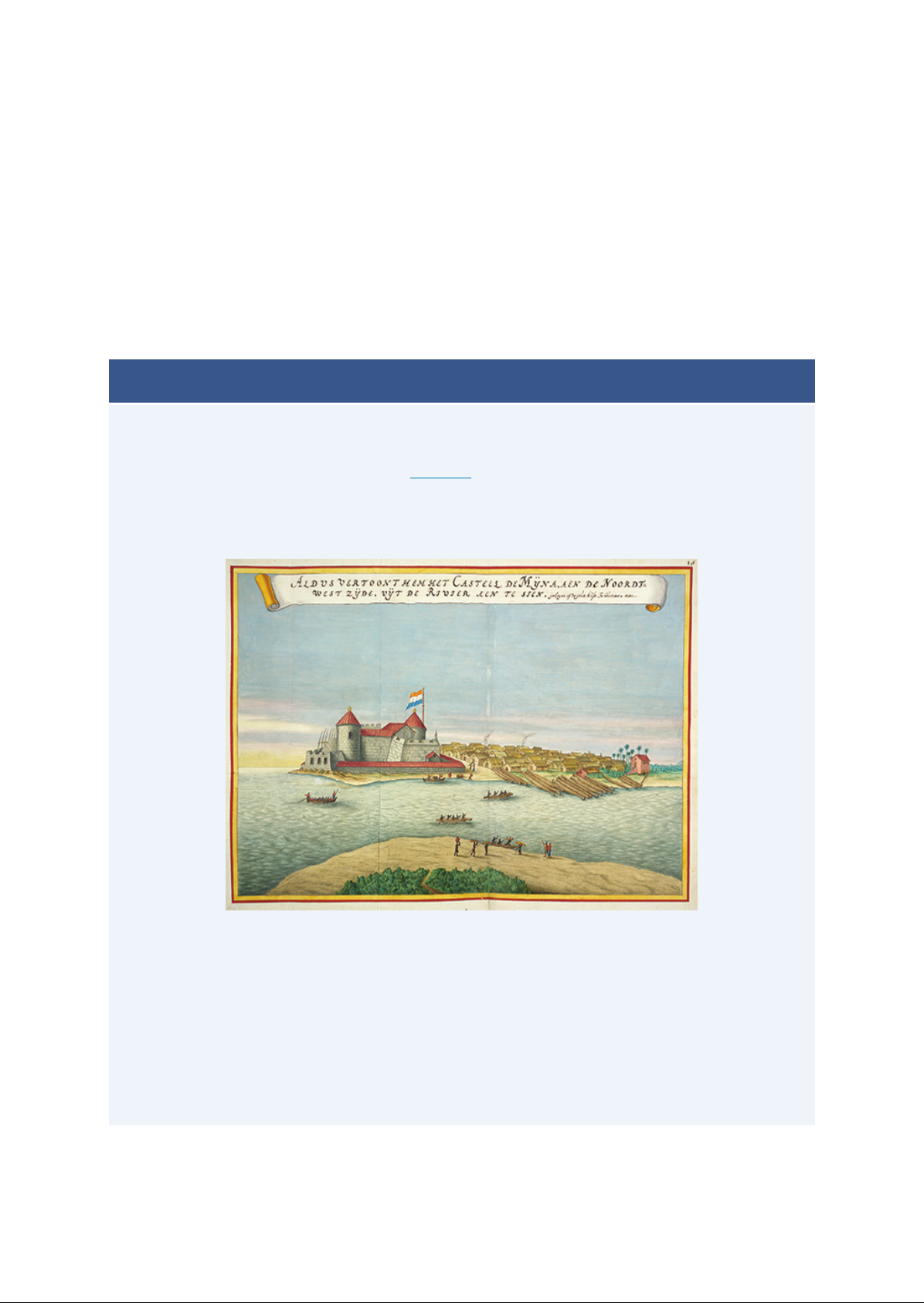

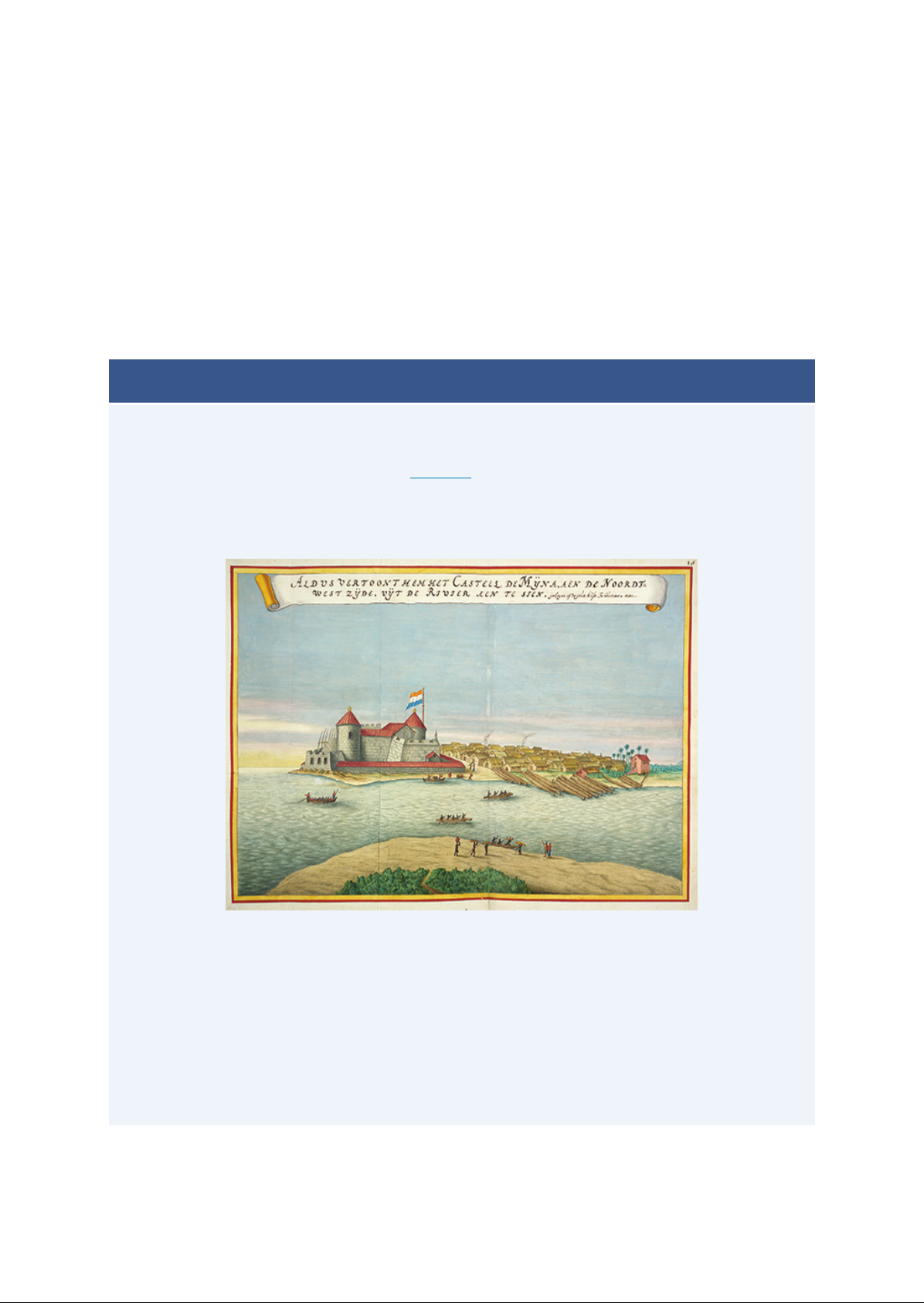

Portuguese Exploration and Spanish Conquest 33 established trading posts in China and Japan . While the Portuguese did rule over an immense landmass , their strategic holdings of islands and coastal ports gave them almost unrivaled control of nautical trade routes and a global empire of trading posts during the . The travels of Portuguese traders to western Africa introduced them to the African slave trade , already brisk among African states . Seeing the value of this source of labor in growing the crop of sugar on their Atlantic islands , the Portuguese soon began exporting enslaved Africans along with African ivory and gold . Sugar fueled the Atlantic slave trade , and the Portuguese islands quickly became home to sugar plantations . The Portuguese also traded these enslaved people , introducing human capital to other European nations . In the following years , as European exploration spread , slavery spread as well . In time , much of the Atlantic World would become a gargantuan complex in which Africans labored to produce the highly commodity for European consumers . AMERICANA Castle In 1482 , Portuguese traders built Castle ( also called Sao Jorge da Mina , or Saint George of the Mine ) in , on the west coast of Africa Figure . A trading post , it had mounted cannons facing out to sea , not inland toward continental Africa the Portuguese had greater fear of a naval attack from other Europeans than of a land attack from Africans . Portuguese traders soon began to settle around the fort and established the town of . on FIGURE Castle on the west coast of was used as a holding pen for captured people before they were brought across the Atlantic and sold . Originally built by the Portuguese in the century , it appears in this image as it was in the , after being seized by Dutch slave traders in 1637 . Although the Portuguese originally used the fort primarily for trading gold , by the sixteenth century they had shifted their focus The dungeon of the fort now served as a holding pen for enslaved Africans from the interior of the continent , while on the upper floors Portuguese traders ate , slept , and prayed in a chapel Enslaved people lived in the dungeon for weeks or months until ships arrived to transport them to Europe or the Americas . For them , the dungeon of was their last sight of their home country . SPANISH EXPLORATION AND CONQUEST The Spanish established the European settlements in the Americas , beginning in the Caribbean and , by

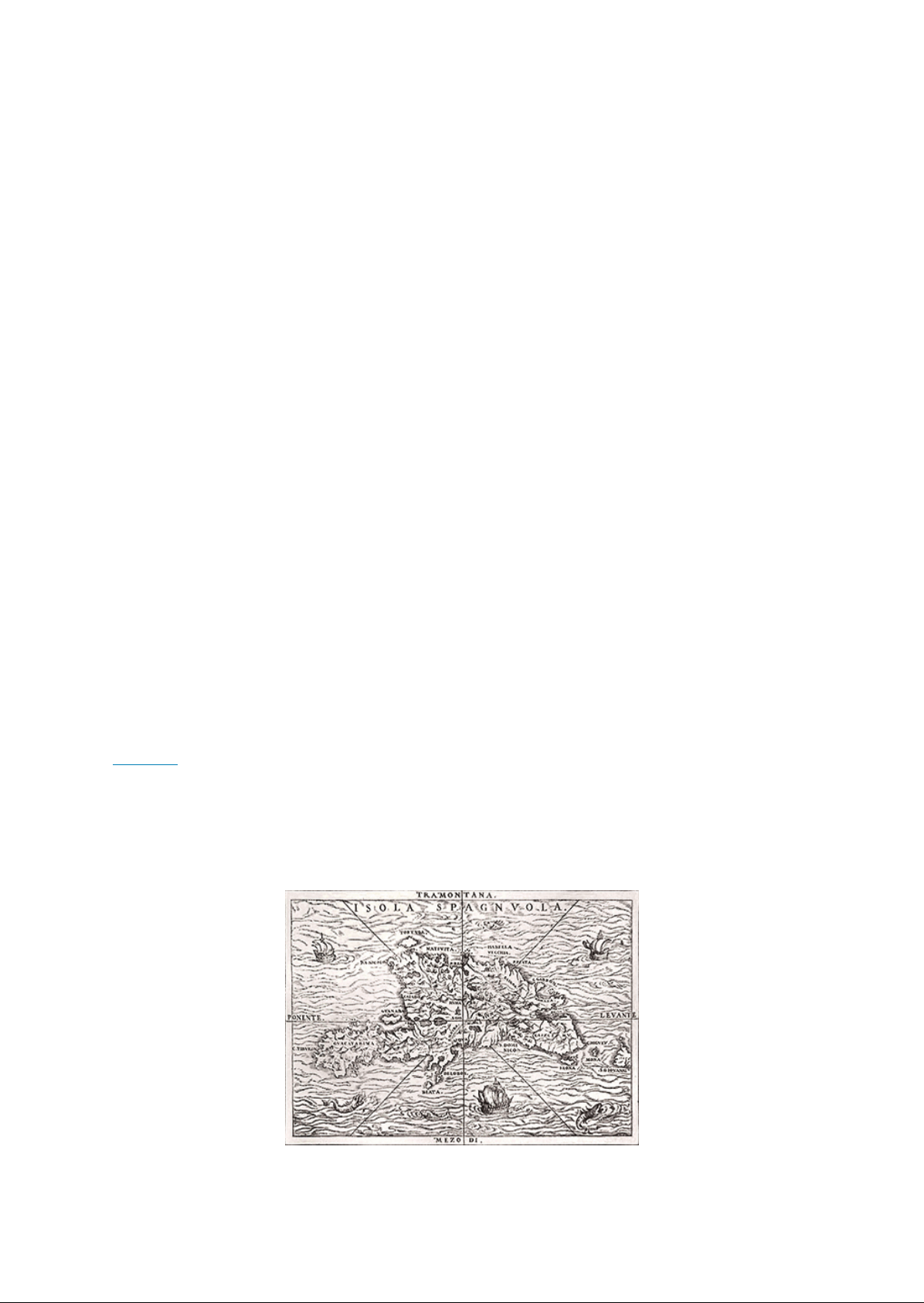

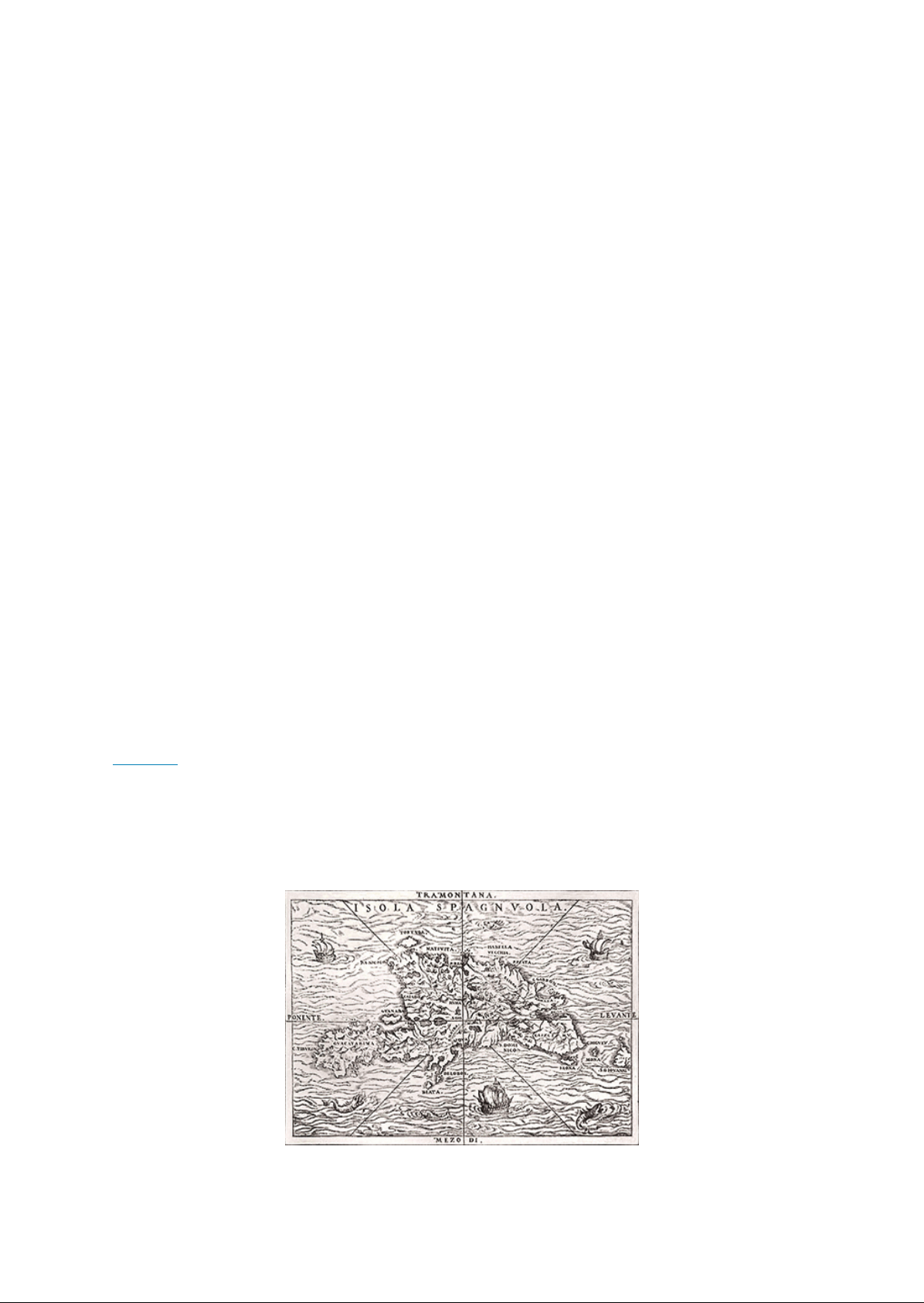

34 Early The Atlantic World , 1600 , extending throughout Central and South America . Thousands of Spaniards to the Americas seeking wealth and status . The most famous of these Spanish adventurers are Christopher Columbus ( who , though Italian himself , explored on behalf of the Spanish monarchs ) Hernan , and Francisco Pizarro . The history of Spanish exploration begins with the history of Spain itself . During the century , Spain hoped to gain advantage over its rival , Portugal . The marriage of Ferdinand of and Isabella of Castile in 1469 Catholic Spain and began the process of building a nation that could compete for worldwide power . Since the 7005 , much of Spain had been under Islamic rule , and King Ferdinand II and Queen Isabella I , of the Catholic Church against Islam , were determined to defeat the Muslims in Granada , the last Islamic stronghold in Spain . In 1492 , they completed the the Christian conquest of the Iberian Peninsula . The marked another step forward in the process of making Spain an imperial power , and Ferdinand and Isabella were now ready to look further . Their goals were to expand Catholicism and to gain a commercial advantage over Portugal . To those ends , Ferdinand and Isabella sponsored extensive Atlantic exploration . Spain most famous explorer , Christopher Columbus , was actually from Genoa , Italy . He believed that , using calculations based on other mariners journeys , he could chart a westward route to India , which could be used to expand European trade and spread Christianity . Starting in 1485 , he approached Genoese , Venetian , Portuguese , English , and Spanish monarchs , asking for ships and funding to explore this westward route . All those he Ferdinand and Isabella at him their nautical experts all concurred that Columbus estimates of the width of the Atlantic Ocean were far too low . However , after three years of entreaties , and , more important , the completion of the , Ferdinand and Isabella agreed to Columbus expedition in 1492 , supplying him with three ships the Nina , the Pinta , and the Santa Maria . The Spanish monarchs knew that Portuguese mariners had reached the southern tip of Africa and sailed the Indian Ocean . They understood that the Portuguese would soon reach Asia and , in this competitive race to reach the Far East , the Spanish rulers decided to act . Columbus held erroneous views that shaped his thinking about what he would encounter as he sailed west . He believed the earth to be much smaller than its actual size and , since he did not know of the existence of the Americas , he fully expected to land in Asia . On October 12 , 1492 , however , he made landfall on an island in the Bahamas . He then sailed to an island he named ( Dominican Republic and Haiti ) Figure ) Believing he had landed in the East Indies , Columbus called the native he found there Indios , giving rise to the term Indian for any native people of the New World . Upon Columbus return to Spain , the Spanish crown bestowed on him the title of Admiral of the Ocean Sea and named him governor and viceroy of the lands he had discovered . As a devoted Catholic , Columbus had agreed with Ferdinand and Isabella prior to sailing west that part of the expected wealth from his voyage would be used to continue the against Islam . FIGURE This map shows the island of ( Haiti and Dominican Republic ) Note the various fanciful elements , such as the ships and sea creatures , and consider what the creator Access for free at .

Portuguese Exploration and Spanish Conquest 35 of this map hoped to convey . In addition to navigation , what purpose would such a map have served ?

Columbus 1493 de ( proof of merit ) his discovery of a New World did much to inspire excitement in Europe . de were reports and letters written by Spaniards in the New World to the Spanish crown , designed to win royal patronage . Today they highlight the task of historical work while the letters are primary sources , historians need to understand the context and the culture in which the conquistadors , as the Spanish adventurers came to be called , wrote them and distinguish their bias and subjective nature . While they are with distortions and fabrications , de are still useful in illustrating the expectation of wealth among the explorers as well as their View that native peoples would not pose a serious obstacle to colonization . In 1493 , Columbus sent two copies of a de to the Spanish king and queen and their minister of , Luis de . had supported Columbus voyage , helping him to obtain funding from Ferdinand and Isabella . Copies of the letter were soon circulating all over Europe , spreading news of the wondrous new land that Columbus had discovered . Columbus would make three more voyages over the next decade , establishing Spain settlement in the New World on the island of . Many other Europeans followed in Columbus footsteps , drawn by dreams of winning wealth by sailing west . Another Italian , sailing for the Portuguese crown , explored the South American coastline between 1499 and 1502 . Unlike Columbus , he realized that the Americas were not part of Asia but lands unknown to Europeans . widely published accounts of his voyages fueled speculation and intense interest in the New World among Europeans . Among those who read reports was the German mapmaker Martin . Using the explorer name as a label for the new landmass , attached America to his map of the New World in 1507 , and the name stuck . DEFINING AMERICAN de of 1493 The exploits of the most famous Spanish explorers have provided Western civilization with a narrative of European supremacy and Native American savagery . However , these stories are based on the efforts of conquistadors to secure royal favor through the writing of de ( proofs of merit ) Below are excerpts from Columbus 1493 letter to Luis de , which illustrates how fantastic reports from European explorers gave rise to many myths surrounding the Spanish conquest and the New World . This island , like all the others , is most extensive . It has many ports along the excelling any in many , large , flowing rivers . The land there is elevated , with many mountains and peaks incomparably higher than in the centre isle . They are most beautiful , of a thousand varied forms , accessible , and full of trees of endless varieties , so high that they seem touch the sky , and I have been told that they never lose their foliage . There is honey , and there are many kinds of birds , and a great variety of fruits . Inland there are numerous mines of metals and innumerable people . is a marvel . Its hills and mountains , plains and open country , are rich and fertile for planting and for pasturage , and for and villages . The seaports there are incredibly , as also the rivers , most of which bear gold . The trees , fruits and grasses differ widely from those in Juana . There are many spices and vast mines of gold and other metals in this island . They have no iron , nor steel , nor weapons , nor are they for them , because although they are made men of commanding stature , they appear timid . The only arms they have are sticks of cane , cut when in seed , with a sharpened stick at the end , anc they are afraid to use these . Often I have sent two or three men ashore to some town to converse with them , and the natives came out in great numbers , and as soon as they saw our men arrive , fled without a moment de ay although I protected them from all injury . What does this letter show us about Spanish objectives in the New World ?

How do you think it might have influenced Europeans reading about the New World for he time ?

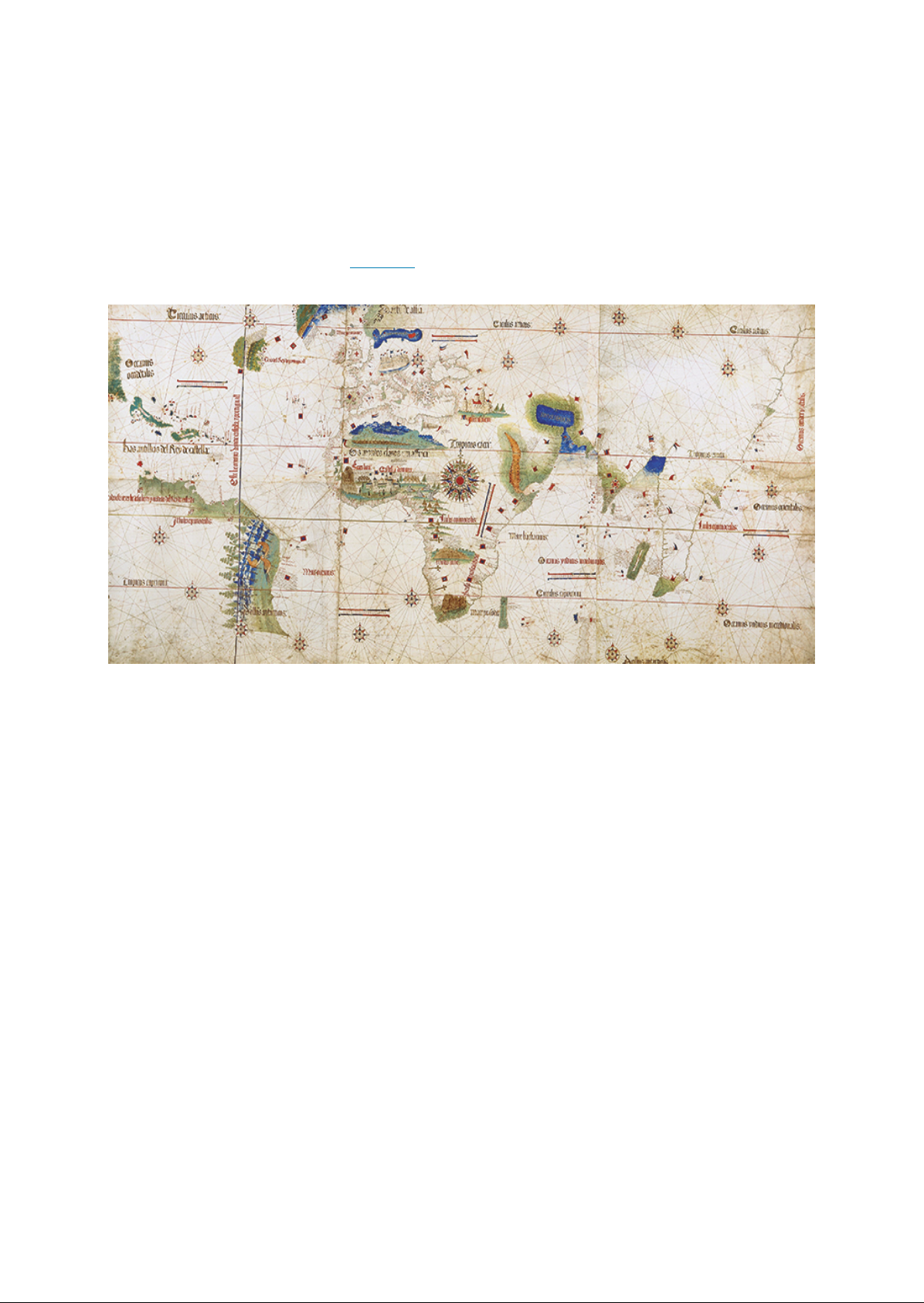

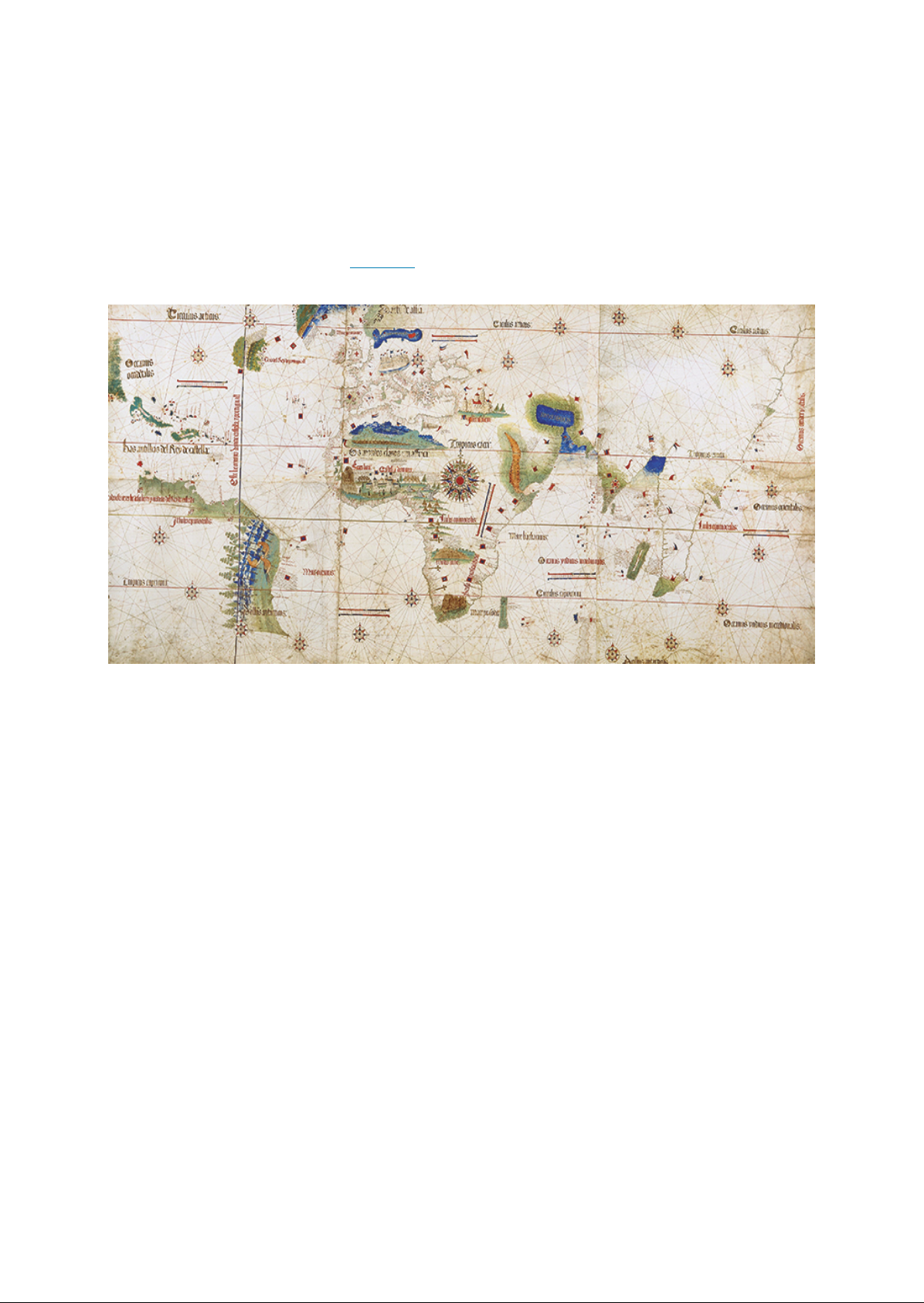

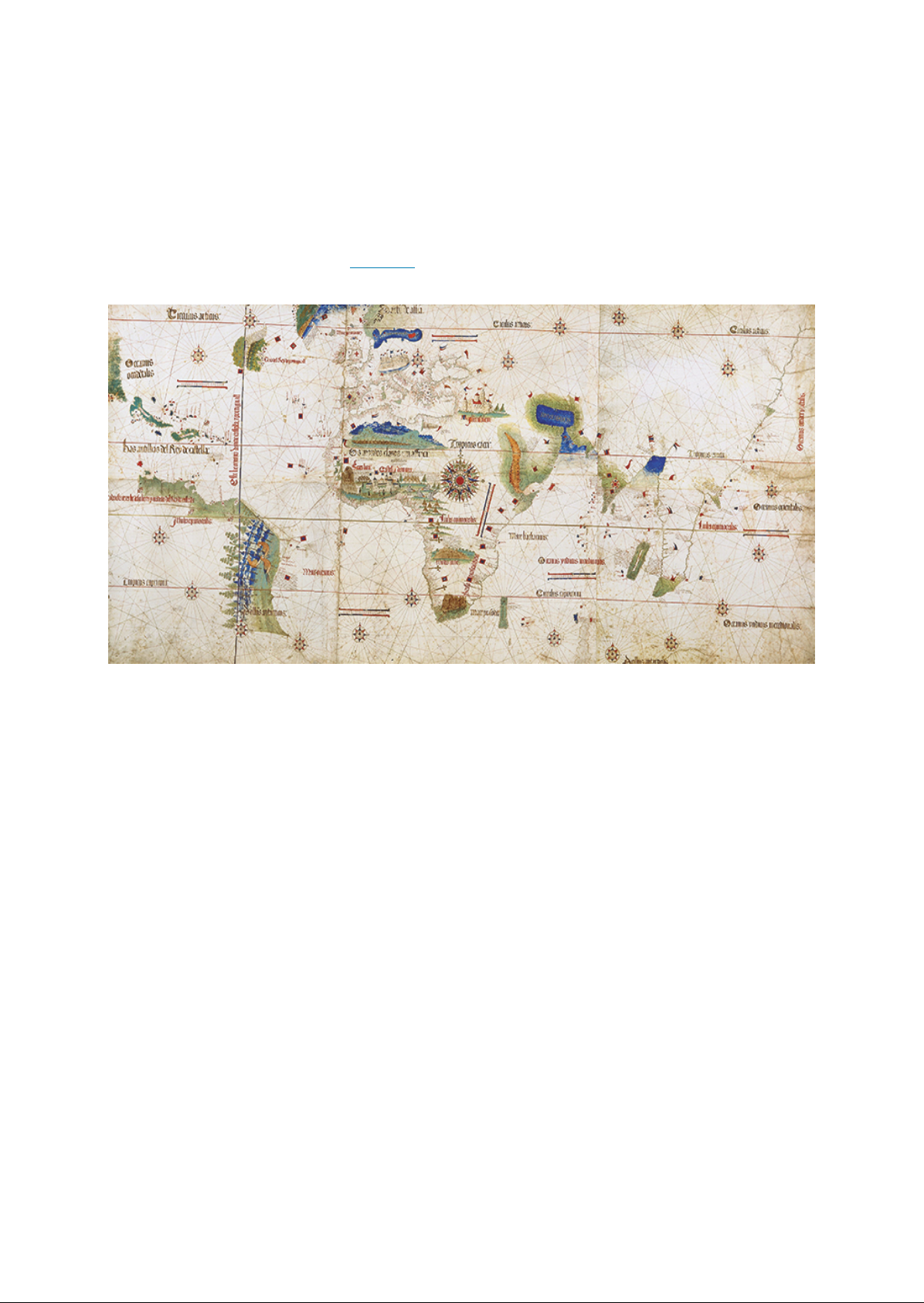

36 Early Globalization The Atlantic World , The 1492 Columbus landfall accelerated the rivalry between Spain and Portugal , and the two powers vied for domination through the acquisition of new lands . In the , Pope IV had granted Portugal the right to all land south of the Cape Verde islands , leading the Portuguese king to claim that the lands discovered by Columbus belonged to Portugal , not Spain . Seeking to ensure that Columbus would remain Spanish , Spain monarchs turned to the Pope Alexander VI , who issued two papal decrees in 1493 that gave legitimacy to Spain Atlantic claims at the expense of Portugal . Hoping to salvage Portugal Atlantic holdings , King Il began negotiations with Spain . The resulting Treaty of in 1494 drew a line through South America ( Figure Spain gained territory west of the line , while Portugal retained the lands east of the line , including the east coast of Brazil . WA I ' Ix . i ' I ' a , I , I . I . I . A . a . A FIGURE This 1502 map , known as the World Map , depicts the cartographer interpretation of the world in light of recent discoveries . The map shows areas of Portuguese and Spanish exploration , the two nations claims under the Treaty of , and a variety of flora , fauna , and structures . What does it reveal about the state of geographical knowledge , as well as European perceptions of the New World , at the beginning of the sixteenth century ?

Columbus discovery opened a of Spanish exploration . Inspired by tales of rivers of gold and timid , malleable natives , later Spanish explorers were relentless in their quest for land and gold . Hernan Cortes hoped to gain hereditary privilege for his family , tribute payments and labor from natives , and an annual pension for his service to the crown . Cortes arrived on in 1504 and took part in the conquest of that island . In anticipation of winning his own honor and riches , Cortes later explored the Yucatan Peninsula . In 1519 , he entered , the capital of the Aztec ( Empire . He and his men were astonished by the incredibly sophisticated causeways , gardens , and temples in the city , but they were by the practice of human that was part of the Aztec religion . Above all else , the Aztec wealth in gold fascinated the Spanish adventurers . Hoping to gain power over the city , Cortes took Moctezuma , the Aztec ruler , hostage . The Spanish then murdered hundreds of during a festival to celebrate , the god of war . This angered the people of , who rose up against the interlopers in their city . Cortes and his people for their lives , running down one of causeways to safety on the shore . Smarting from their defeat at the hands of the Aztec , Cortes slowly created alliances with native peoples who resented Aztec rule . It took nearly a year for the Spanish and the tens of thousands of native allies who joined them to defeat the in , which they did by laying siege to the city . Only by playing upon the disunity among the diverse groups in the Aztec Empire were the Spanish able to capture the grand city of . In August 1521 , having successfully fomented civil war as well as fended off rival Spanish explorers , Cortes claimed Access for free at .

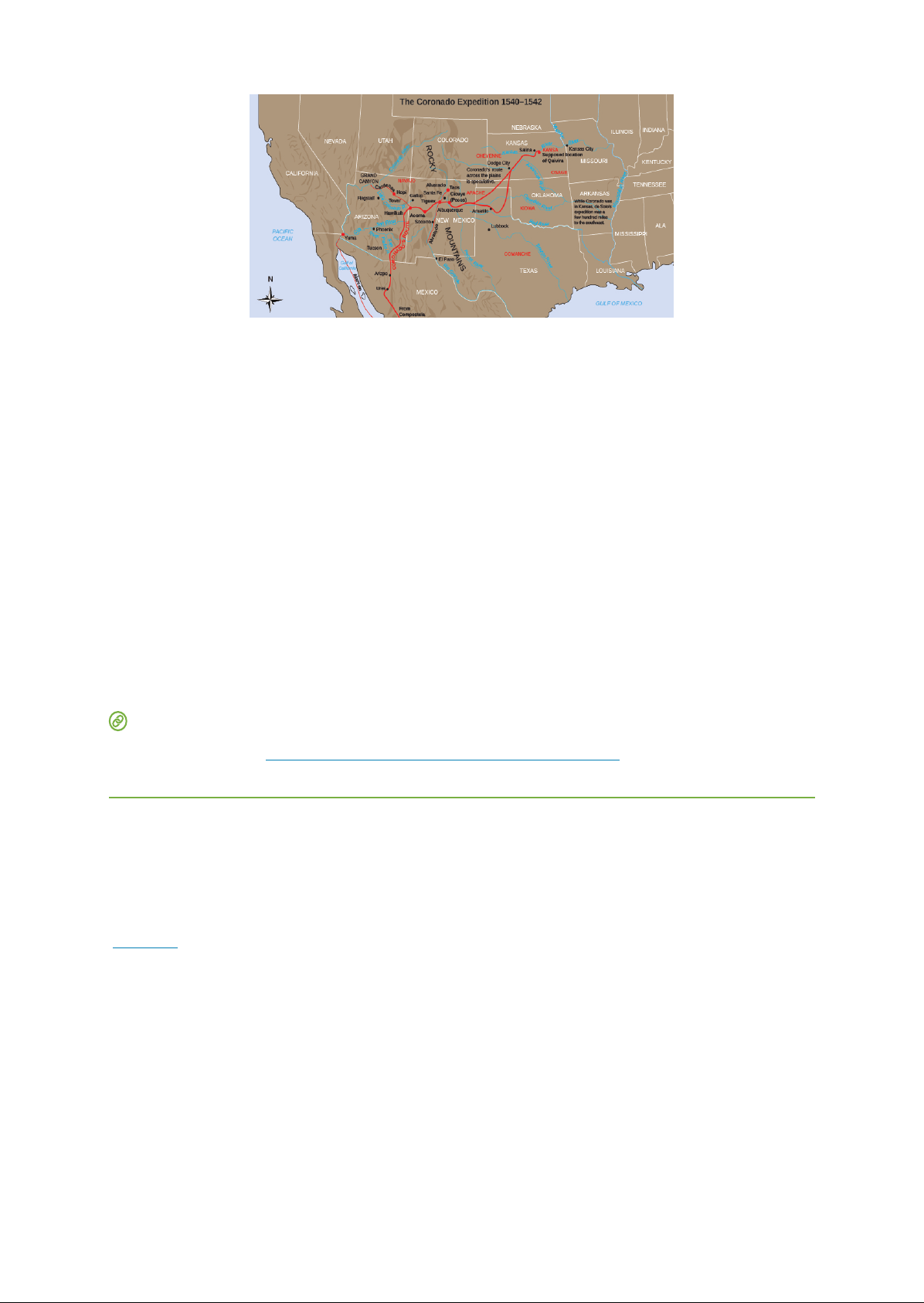

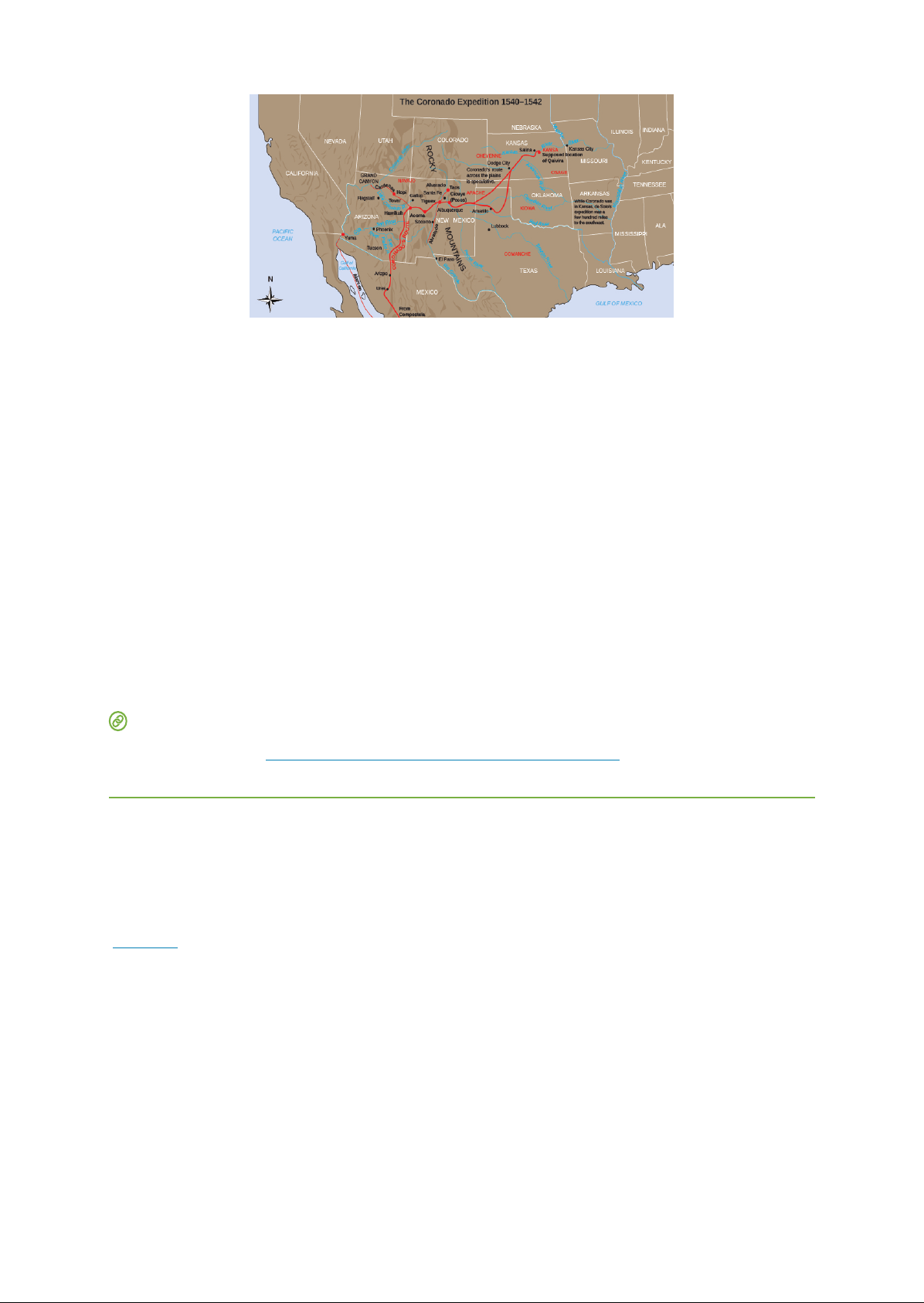

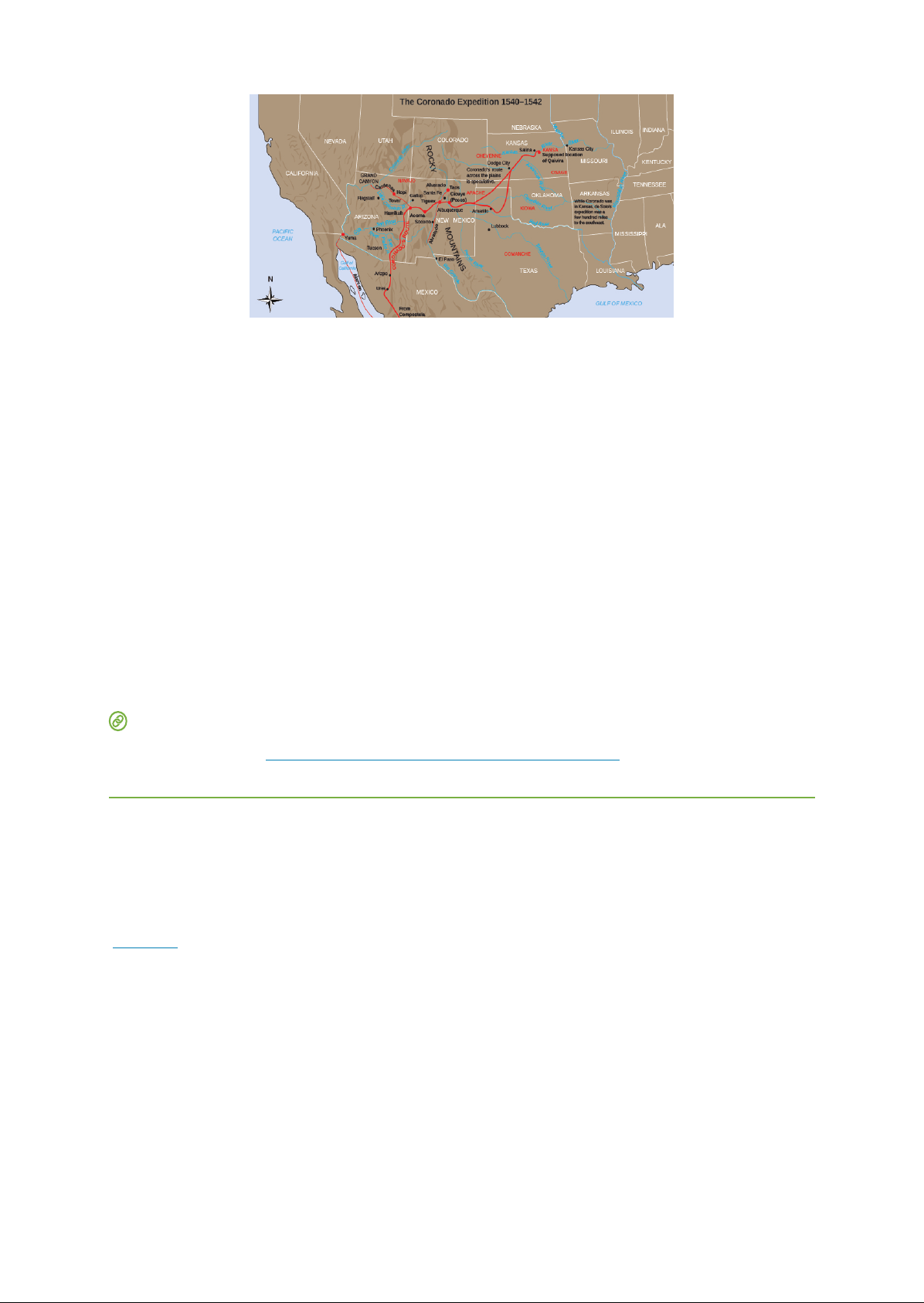

Portuguese Exploration and Spanish Conquest 37 for Spain and renamed it Mexico City . The traditional European narrative of exploration presents the victory of the Spanish over the Aztec as an example of the superiority of the Europeans over the savage Indians . However , the reality is far more complex . When Cortes explored central Mexico , he encountered a region simmering with . Far from being and content under Aztec rule , many peoples in Mexico resented it and were ready to rebel . One group in particular , the , threw their lot in with the Spanish , providing as many as in the siege of . The Spanish also brought smallpox into the valley of Mexico . The disease took a heavy toll on the people in , playing a much greater role in the city demise than did Spanish force of arms . Cortes was also aided by a woman called ( also known as La or Dona Marina , her Spanish name ) whom the natives of Tabasco gave him as tribute . translated for Cortes in his dealings with Moctezuma and , whether willingly or under pressure , entered into a physical relationship with him . Their son , Martin , may have been the mestizo ( person of mixed indigenous American and European descent ) remains a controversial in the history of the Atlantic World some people view her as a traitor because she helped Cortes conquer the Aztecs , while others see her as a victim of European expansion . In either case , she demonstrates one way in which native peoples responded to the arrival of the Spanish . Without her , Cortes would not have been able to communicate , and without the language bridge , he surely would have been less successful in destabilizing the Aztec Empire . By this and other means , native people helped shape the conquest of the Americas . Spain acquisitiveness seemingly knew no bounds as groups of its explorers searched for the next trove of instant riches . One such explorer , Francisco Pizarro , made his way to the Spanish Caribbean in 1509 , drawn by the promise of wealth and titles . He participated in successful expeditions in Panama before following rumors of Inca wealth to the south . Although his efforts against the Inca Empire in the failed , Pizarro captured the Inca emperor in 1532 and executed him one year later . In 1533 , Pizarro founded Lima , Peru . Like Cortes , Pizarro had to combat not only the natives of the new worlds he was conquering , but also competitors from his own country a Spanish rival assassinated him in 1541 . Spain drive to enlarge its empire led other hopeful conquistadors to push further into the Americas , hoping to replicate the success of Cortes and Pizarro . de Soto had participated in Pizarro conquest of the Inca , and from 1539 to 1542 he led expeditions to what is today the southeastern United States , looking for gold . He and his followers explored what is now Florida , Georgia , the Carolinas , Tennessee , Alabama , Mississippi , Arkansas , Oklahoma , Louisiana , and Texas . Everywhere they traveled , they brought European diseases , which claimed thousands of native lives as well as the lives of the explorers . In 1542 , de Soto himself died during the expedition . The surviving Spaniards , numbering a little over three hundred , returned to Mexico City without the mountains of gold and silver . Francisco Vasquez de Coronado was born into a noble family and went to Mexico , then called New Spain , in 1535 . He presided as governor over the province of Nueva , where he heard rumors of wealth to the north a golden city called . Between 1540 and 1542 , Coronado led a large expedition of Spaniards and native allies to the lands north of Mexico City , and for the next several years , they explored the area that is now the southwestern United States ( Figure . During the winter of , the explorers waged war against the in New Mexico . Rather than leading to the discovery of gold and silver , however , the expedition simply left Coronado bankrupt .

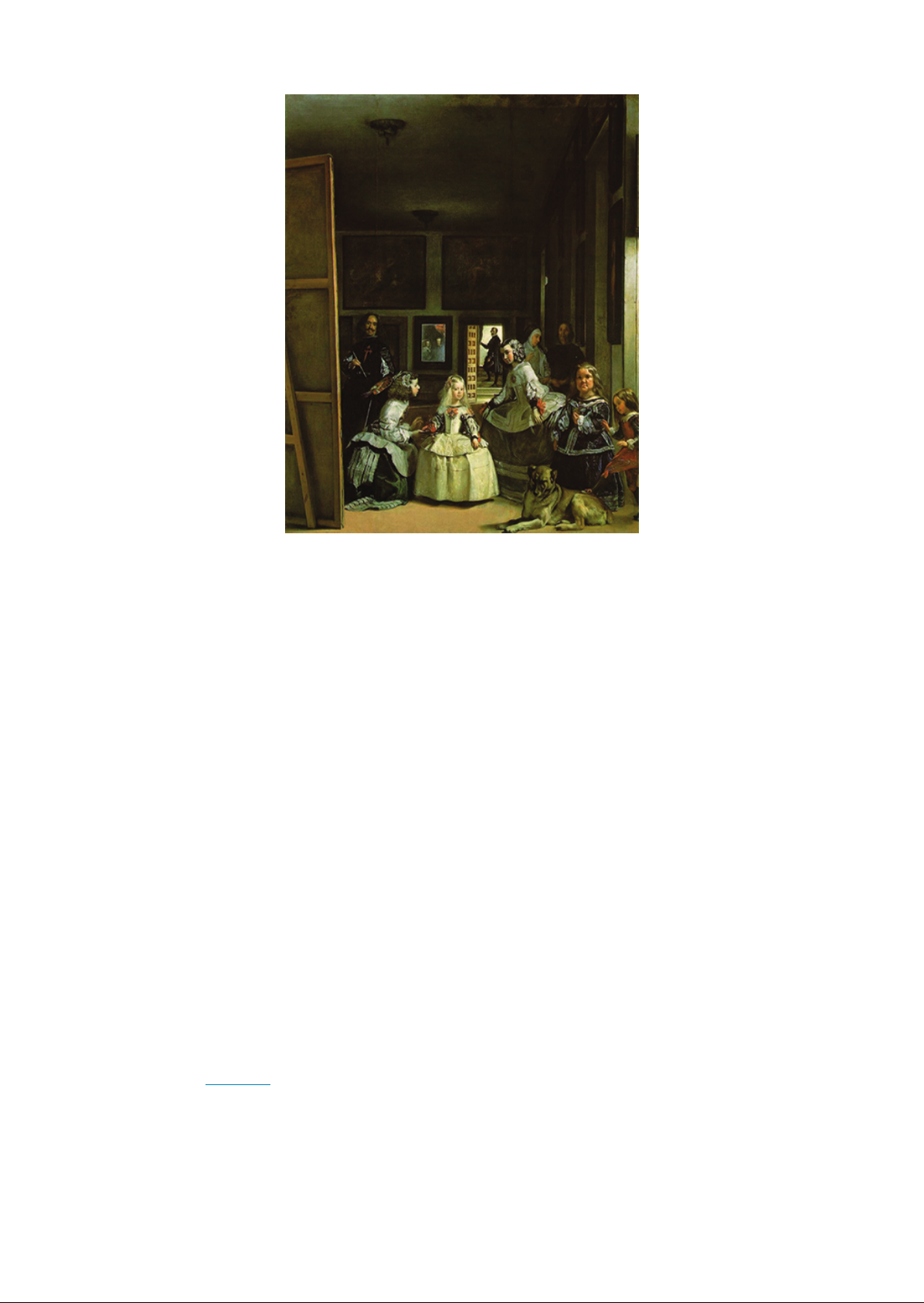

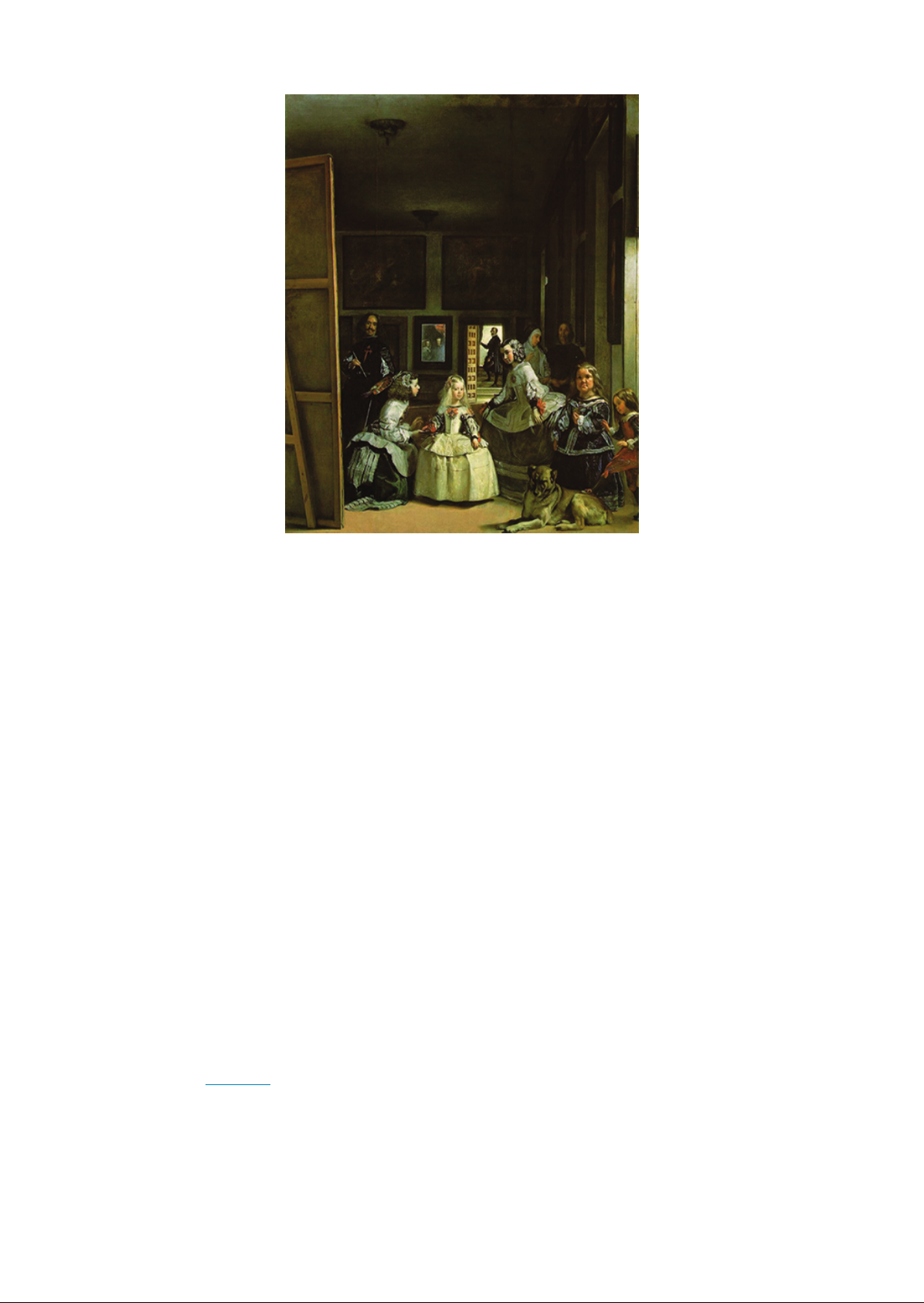

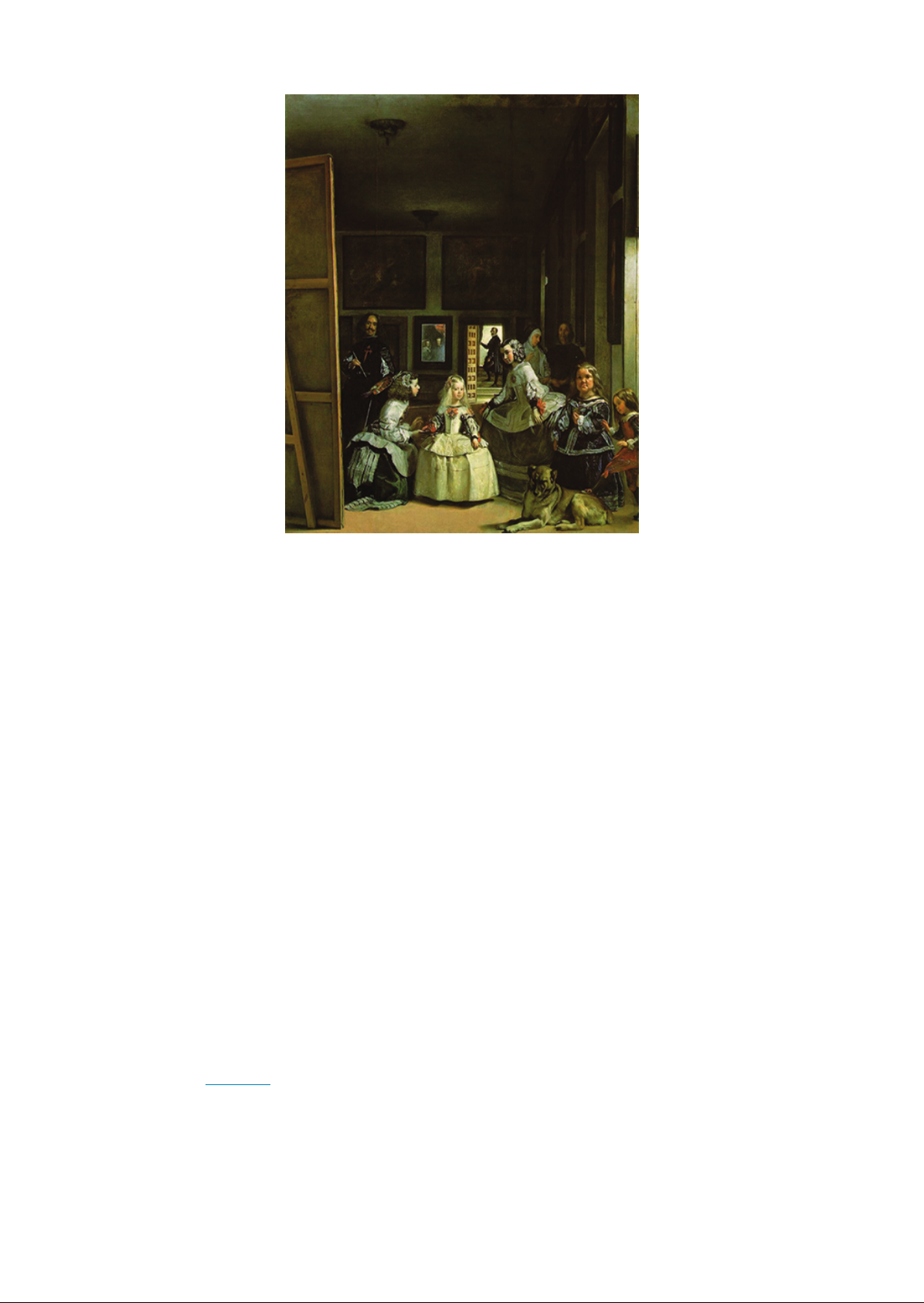

38 Early Globalization The Atlantic World , our FIGURE This map traces Coronado path through the American Southwest and the Great Plains . The regions through which he traveled were not empty areas waiting to be discovered rather , they were populated and controlled by the groups of native peoples indicated . credit of work by National Park Service ) THE SPANISH GOLDEN AGE The exploits of European explorers had a profound impact both in the Americas and back in Europe . An exchange of ideas , fueled and in part by New World commodities , began to connect European nations and , in turn , to touch the parts of the world that Europeans conquered . In Spain , gold and silver from the Americas helped to fuel a golden age , the de Oro , when Spanish art and literature . Riches poured in from the colonies , and new ideas poured in from other countries and new lands . The Hapsburg dynasty , which ruled a collection of territories including Austria , the Netherlands , Naples , Sicily , and Spain , encouraged and the work of painters , sculptors , musicians , architects , and writers , resulting in a blooming of Spanish Renaissance culture . One of this period most famous works is the novel The Ingenious Gentleman Don Quixote of La , by Miguel de Cervantes . This book ( 1605 and 1618 ) told a colorful tale of an ( gentleman ) who reads so many tales of chivalry and knighthood that he becomes unable to tell reality from . With his faithful sidekick Sancho Panza , Don Quixote leaves reality behind and sets out to revive chivalry by doing battle with what he perceives as the enemies of Spain . cLIcK AND EXPLORE Explore the collection at The Cervantes Proiect ( for images , complete texts , and other resources relating to Cervantes works . Spain attracted innovative foreign painters such as El , a Greek who had studied with Italian Renaissance masters like Titian and Michelangelo before moving to Toledo . Native Spaniards created equally enduring works . Las ( The Maids of Honor ) painted by Diego in 1656 , is one of the paintings in history . painted himself into this imposingly large royal portrait ( he shown holding his brush and easel on the left ) and boldly placed the viewer where the king and queen would stand in the scene Figure ) Access for free at .

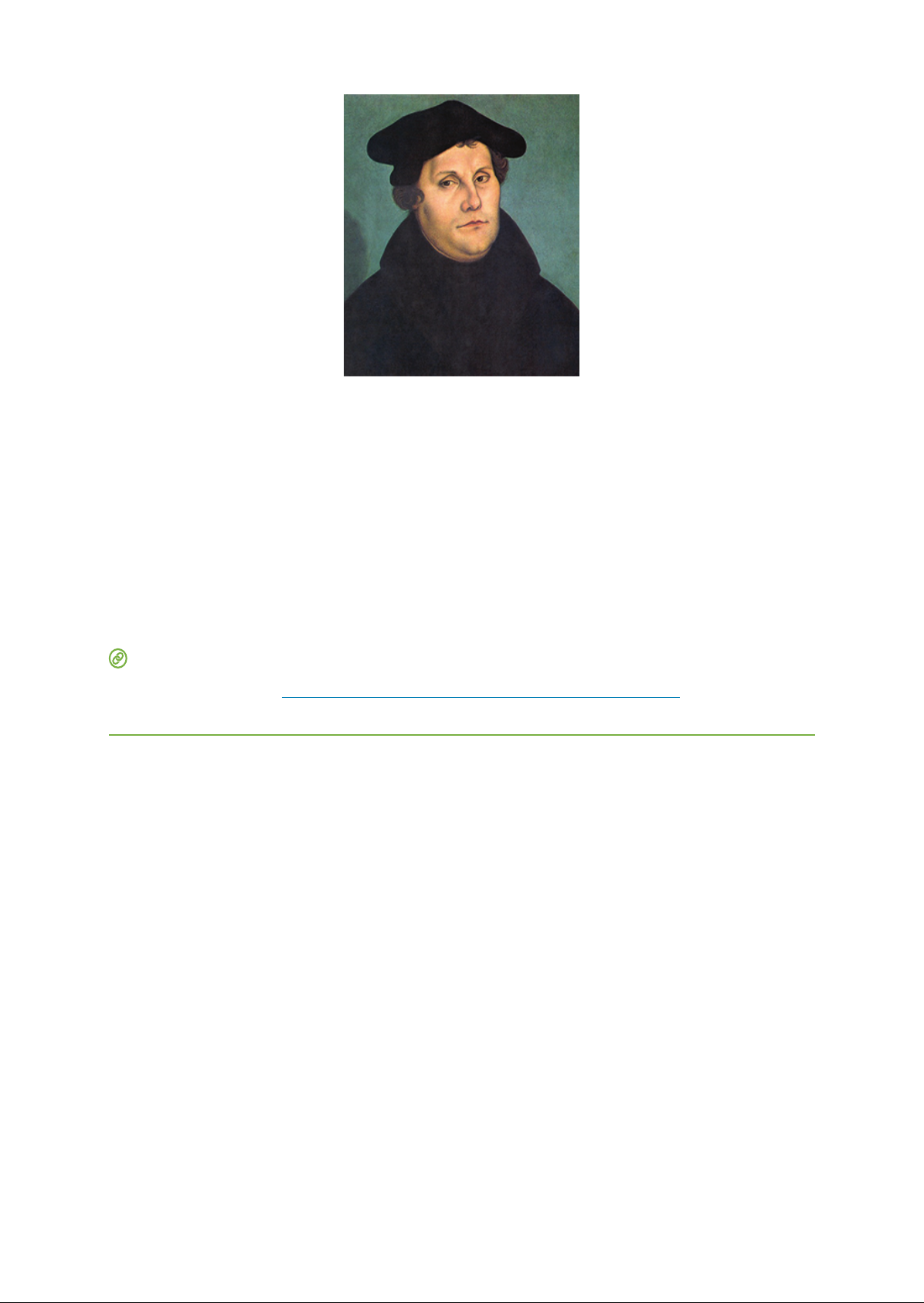

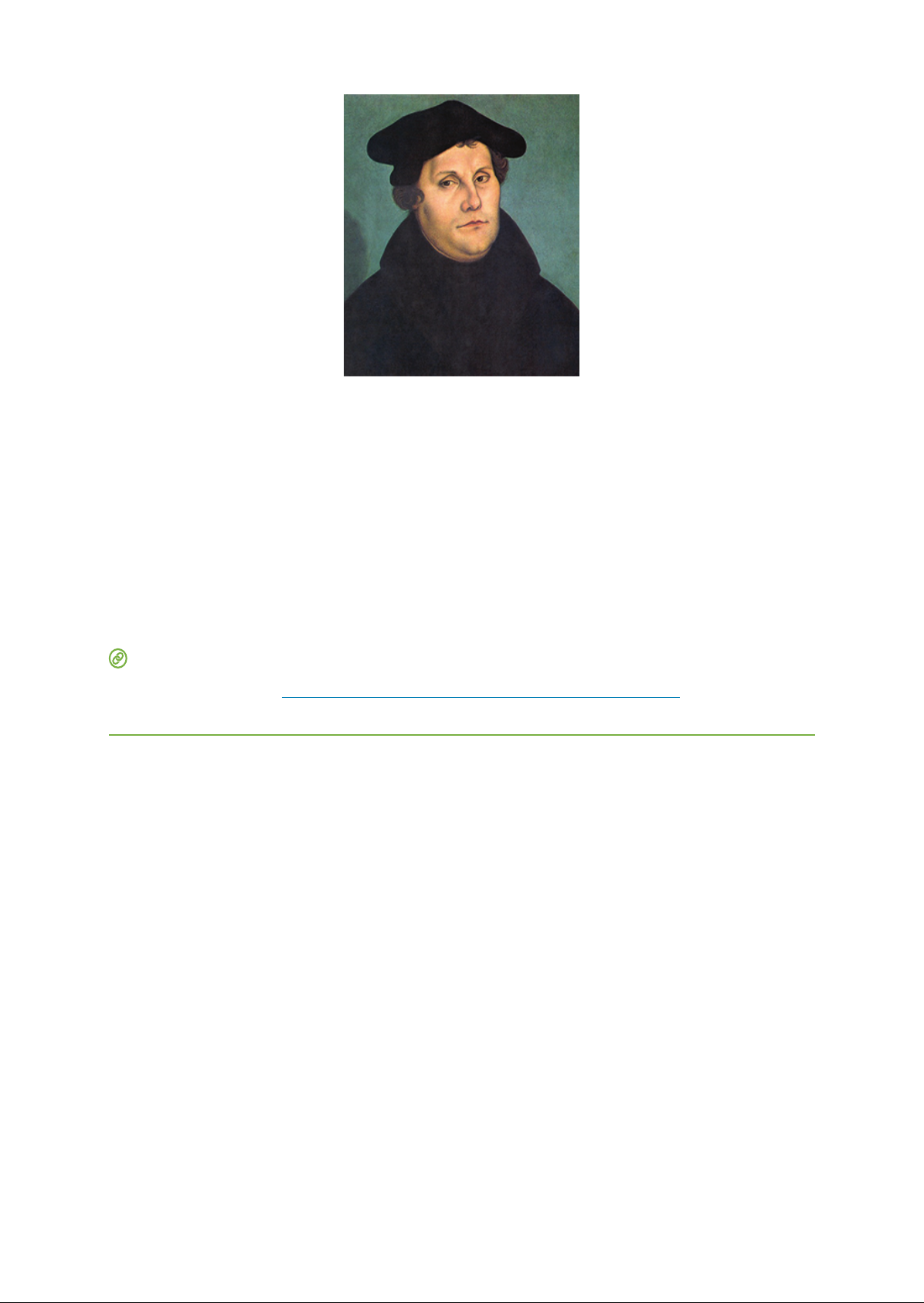

Religious Upheavals in the Developing Atlantic World 39 FIGURE Las ( The Maids of Honor ) painted by Diego in 1656 , is unique for its time because it places the viewer in the place of King Philip IV and his wife , Queen Mariana . Religious Upheavals in the Developing Atlantic World LEARNING OBJECTIVES By the end ofthis section , you will be able to Explain the changes brought by the Protestant Reformation and how it influenced the development ofthe Atlantic World Describe Spain response to the Protestant Reformation Until the , the Catholic Church provided a unifying religious structure for Christian Europe . The Vatican in Rome exercised great power over the lives of Europeans it controlled not only learning and scholarship but also , because it levied taxes on the faithful . Spain , with its New World wealth , was the bastion of the Catholic faith . Beginning with the reform efforts of Martin Luther in 1517 and John Calvin in the 15305 , however , Catholic dominance came under attack as the Protestant Reformation , a split or schism among European Christians , began . During the sixteenth century , Protestantism spread through northern Europe , and Catholic countries responded by attempting to extinguish what was seen as the Protestant menace . Religious turmoil between Catholics and Protestants the history of the Atlantic World as well , since different competed not only for control of new territories but also for the preeminence of their religious beliefs there . Just as the history of Spain rise to power is linked to the , so too is the history of early globalization connected to the history of competing Christian groups in the Atlantic World . MARTIN LUTHER Martin Luther Figure was a German Catholic monk who took issue with the Catholic Church practice of selling indulgences , documents that absolved sinners of their errant behavior . He also objected to the Catholic Church taxation of ordinary Germans and the delivery of Mass in Latin , arguing that it failed to instruct German Catholics , who did not understand the language .

40 Early The Atlantic World , FIGURE Martin Luther , a German Catholic monk and leader of the Protestant Reformation , was a close friend of the German painter Lucas the Elder . painted this and several other portraits of Luther . Many Europeans had called for reforms of the Catholic Church before Martin Luther did , but his protest had the unintended consequence of splitting European Christianity . Luther compiled a list of what he viewed as needed Church reforms , a document that came to be known as The Theses , and nailed it to the door of a church in , Germany , in 1517 . He called for the publication of the Bible in everyday language , took issue with the Church policy of imposing tithes ( a required payment to the Church that appeared to enrich the clergy ) and denounced the buying and selling of indulgences . Although he had hoped to reform the Catholic Church while remaining a part of it , Luther action instead triggered a movement called the Protestant Reformation that divided the Church in two . The Catholic Church condemned him as a heretic , but a doctrine based on his reforms , called , spread through northern Germany and . CLICK AND EXPLORE Visit Fordham University Internet Medieval ( for access to many primary sources relating to the Protestant Reformation . JOHN CALVIN Like Luther , the French lawyer John Calvin advocated making the Bible accessible to ordinary people only by reading scripture and daily about their spiritual condition , he argued , could believers begin to understand the power of God . In 1535 , Calvin Catholic France and led the Reformation movement from Geneva , Switzerland . emphasized human powerlessness before an omniscient God and stressed the idea of predestination , the belief that God selected a few chosen people for salvation while everyone else was predestined to damnation . Calvinists believed that reading scripture prepared sinners , if they were among the elect , to receive God grace . In Geneva , Calvin established a Bible commonwealth , a community of believers whose sole source of authority was their interpretation of the Bible , not the authority of any prince or monarch . Soon Calvin ideas spread to the Netherlands and Scotland . PROTESTANTISM IN ENGLAND Protestantism spread beyond the German states and Geneva to England , which had been a Catholic nation for centuries . Luther idea that scripture should be available in the everyday language of worshippers inspired English scholar William to translate the Bible into English in 1526 . The seismic break with the Catholic Church in England occurred in the , when Henry VIII established a new , Protestant state religion . Access for free at .

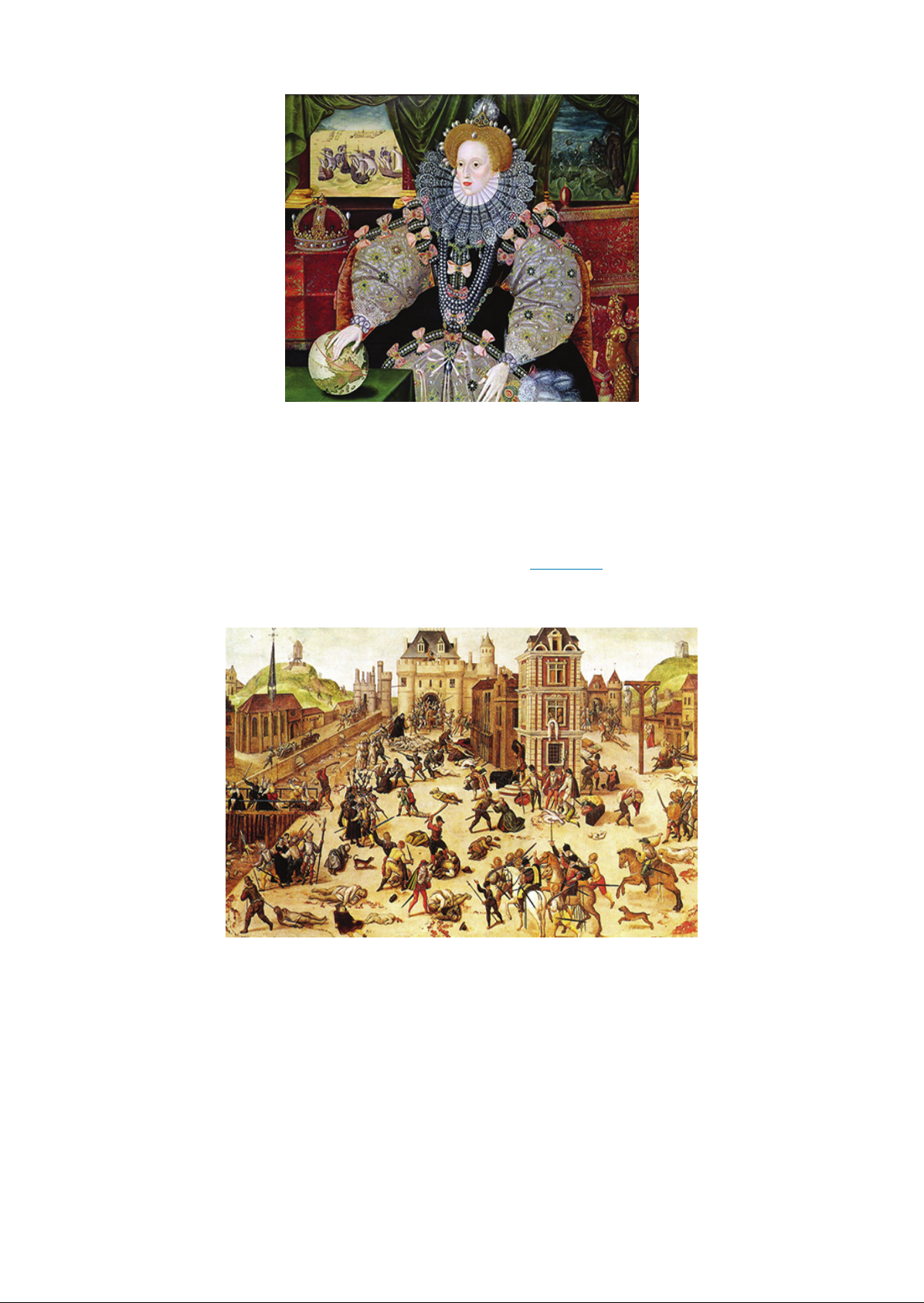

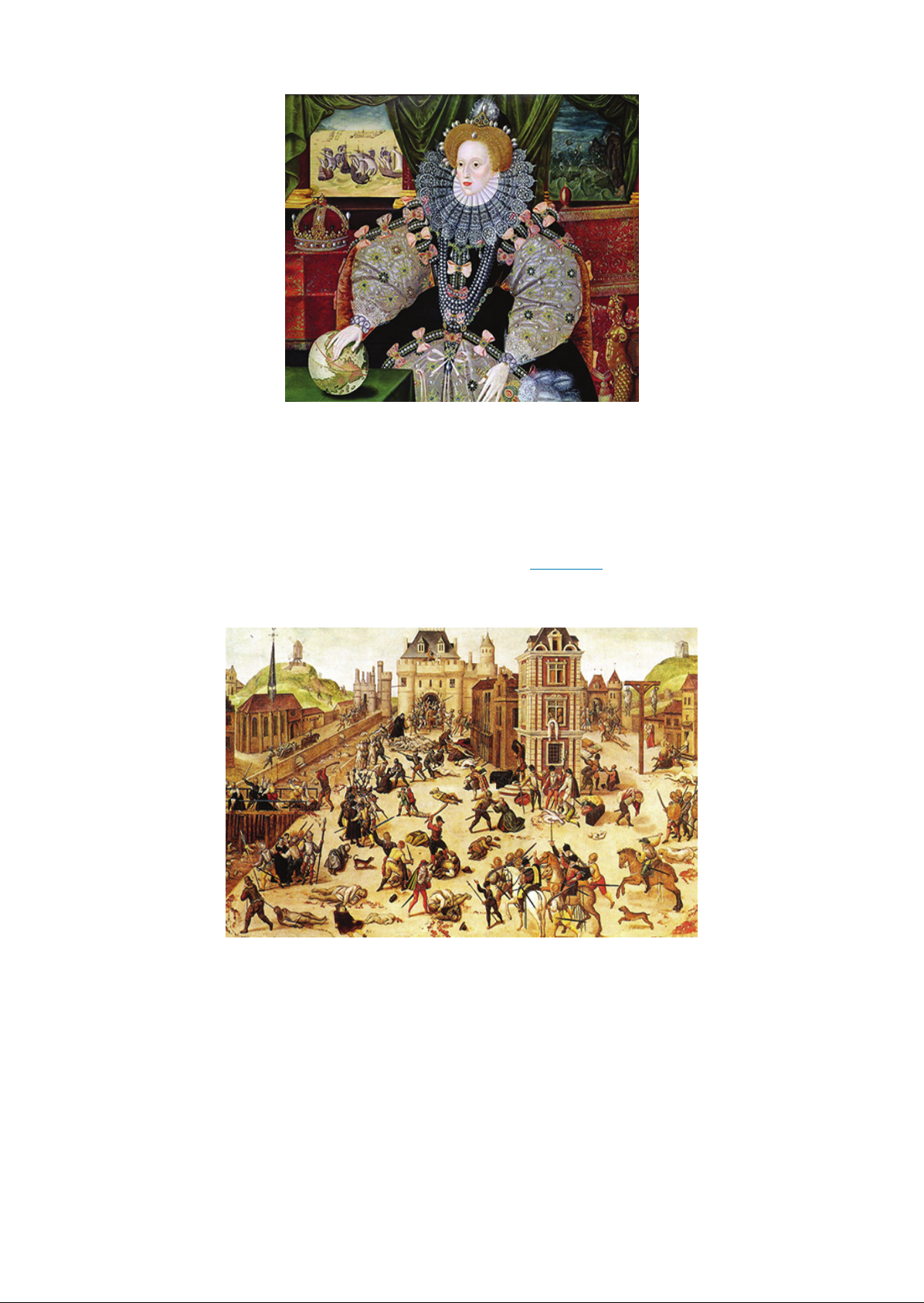

Religious Upheavals in the Developing Atlantic World 41 A devout Catholic , Henry had initially stood in opposition to the Reformation . Pope Leo even awarded him the title Defender of the The tides turned , however , when Henry desired a male heir to the Tudor monarchy . When his Spanish Catholic wife , Catherine ( the daughter of Ferdinand and Isabella ) did not give birth to a boy , the king sought an annulment to their marriage . When the Pope refused his request , Henry created a new national Protestant church , the Church , with himself at its head . This left him free to annul his own marriage and marry Anne Boleyn . Anne Boleyn also failed to produce a male heir , and when she was accused of adultery , Henry had her executed . His third wife , Jane Seymour , at long last delivered a son , Edward , who ruled for only a short time before dying in 1553 at the age of . Mary , the daughter of Henry VIII and his discarded first wife Catherine , then came to the throne , committed to restoring Catholicism . She earned the nickname Bloody Mary for the many executions of Protestants , often by burning alive , that she ordered during her reign . Religious turbulence in England was quieted when Elizabeth , the Protestant daughter of Henry VIII and Anne Boleyn , ascended the throne in 1558 . Under Elizabeth , the Church of England again became the state church , retaining the hierarchical structure and many of the rituals of the Catholic Church . However , by the late , some English members of the Church began to agitate for more reform . Known as Puritans , they worked to erase all vestiges of Catholicism from the Church of England . At the time , the term puritan was a pejorative one many people saw Puritans as frauds who used religion to swindle their neighbors . Worse still , many in power saw Puritans as a security threat because of their opposition to the national church . Under Elizabeth , whose long reign lasted from 1558 to 1603 , Puritans grew steadily in number After James I died in 1625 and his son Charles I ascended the throne , Puritans became the target of increasing state pressure to conform . Many crossed the Atlantic in the and 16305 instead to create a New England , a haven for reformed Protestantism where Puritan was no longer a term of abuse . Thus , the religious upheavals that affected England so much had equally momentous consequences for the Americas . RELIGIOUS WAR By the early , the Protestant Reformation threatened the massive Spanish Catholic empire . As the preeminent Catholic power , Spain would not tolerate any challenge to the Holy Catholic Church . Over the course of the , it devoted vast amounts of treasure and labor to leading an unsuccessful effort to eradicate Protestantism in Europe . Spain main enemies at this time were the runaway Spanish provinces of the North Netherlands . By 1581 , these seven northern provinces had declared their independence from Spain and created the Dutch Republic , also called land , where Protestantism was tolerated . Determined to deal a death blow to Protestantism in England and , King Philip of Spain assembled a massive force of over thirty thousand men and 130 ships , and in 1588 he sent this navy , the Spanish Armada , north . But English sea power combined with a maritime storm destroyed the . The defeat of Spanish Armada in 1588 was but one part of a larger but undeclared war between Protestant England and Catholic Spain . Between 1585 and 1604 , the two rivals sparred repeatedly . England launched its own armada in 1589 in an effort to disable the Spanish and capture Spanish treasure . However , the foray ended in er for the English , with storms , disease , and the strength of the Spanish Armada combining to bring about de eat . The be ween Spain and England dragged on into the early seventeenth century , and the newly Protestant nations , especially England and the Dutch Republic , posed a challenge to Spain ( and also to Catholic France ) as imperial rivalries played out in the Atlantic World . Spain retained its mighty American empire , but by he early , the nation could no longer keep England and other European French and Du colonizing smaller islands in the Caribbean ( Figure .

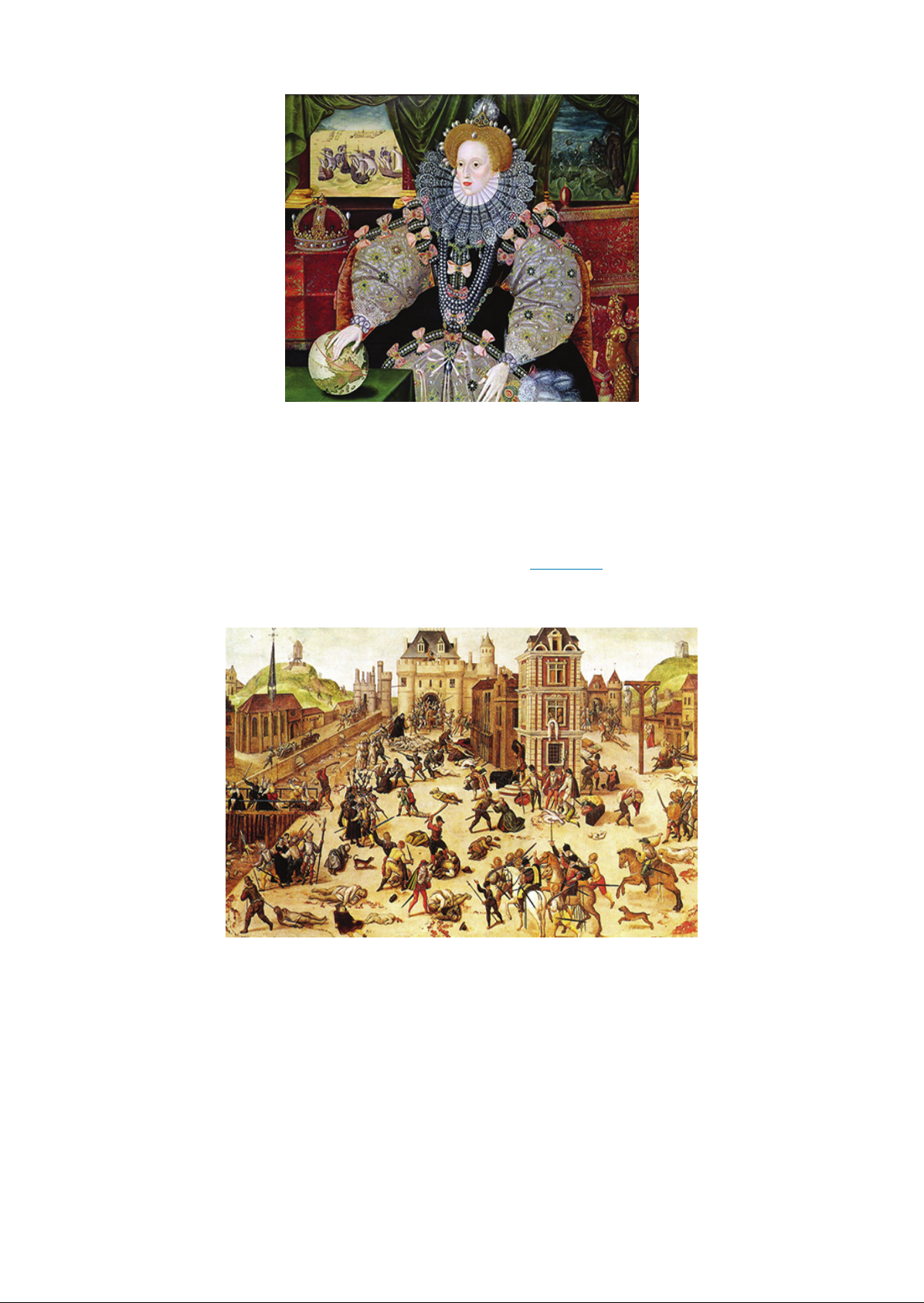

42 Early Globalization The Atlantic World , FIGURE This portrait of Elizabeth I of England , painted by George in about 1588 , shows Elizabeth with her hand on a globe , signifying her power over the world . The pictures in the background show the English defeat of the Spanish Armada . Religious intolerance characterized the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries , an age of powerful state religions with the authority to impose and enforce belief systems on the population . In this climate , religious violence was common . One of the most striking examples is the Bartholomew Day Massacre of 1572 , in which French Catholic troops began to kill unarmed French Protestants Figure . The murders touched off mob violence that ultimately claimed nine thousand lives , a bloody episode that highlights the degree of religious turmoil that gripped Europe in the aftermath of the Protestant Reformation . av FIGURE Saint Bartholomew Day Massacre ( by Francois Dubois , shows the violence of the Bartholomew Day Massacre . In this scene , French Catholic troops slaughter French Protestant Calvinists . Challenges to Spain Supremacy LEARNING OBJECTIVES By the end ofthis section , you will be able to Identify regions where the English , French , and Dutch explored and established settlements Describe the differences among the early colonies Explain the role of the American colonies in European nations struggles for domination For Europeans , the discovery of an Atlantic World meant newfound wealth in the form of gold and silver as well as valuable furs . The Americas also provided a new arena for intense imperial rivalry as different European Access for free at .

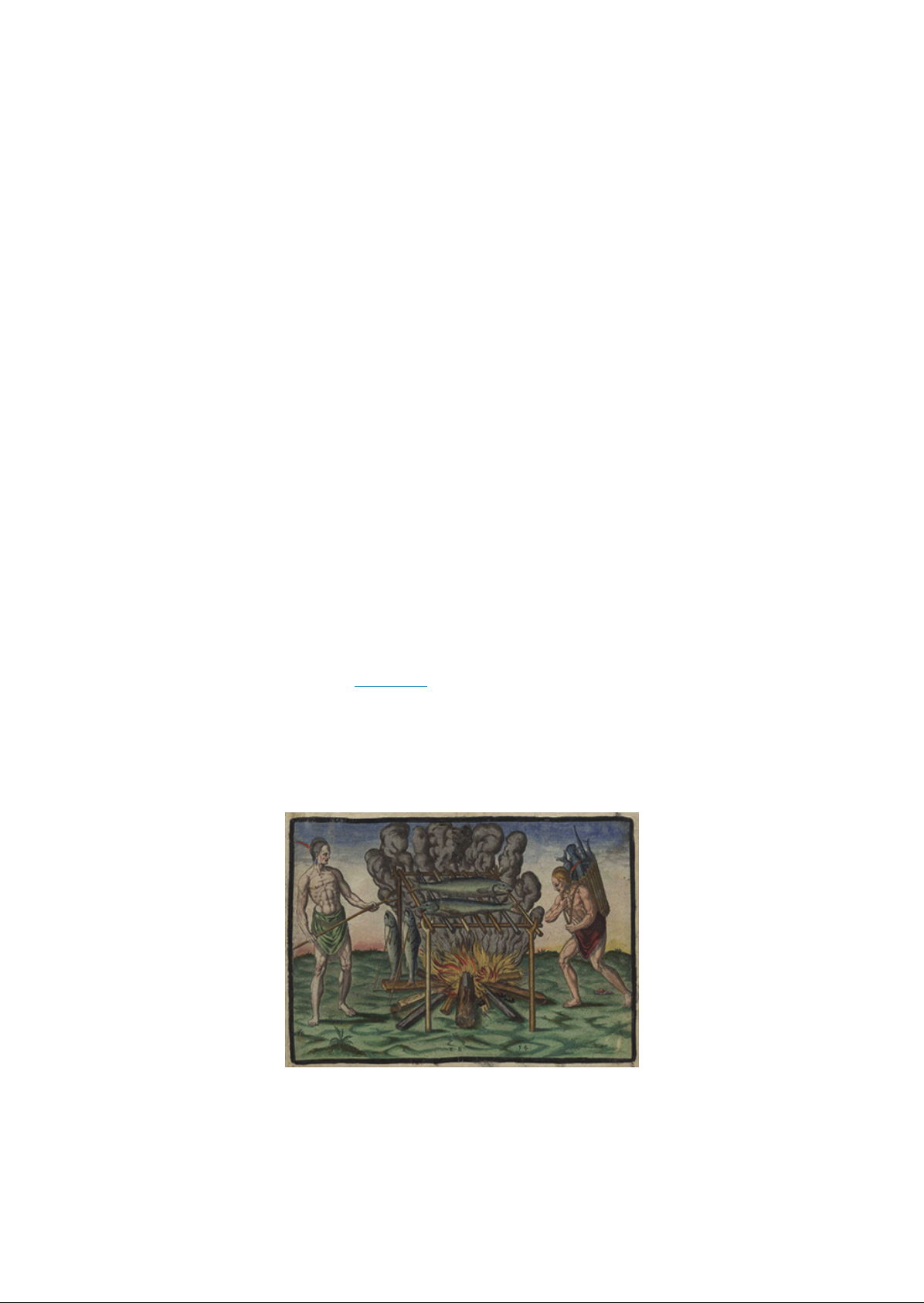

Challenges to Spain Supremacy 43 nations jockeyed for preeminence in the New World . The religious motives for colonization spurred European expansion as well , and as the Protestant Reformation gained ground beginning in the , rivalries between Catholic and Protestant Christians spilled over into the Americas . ENGLISH EXPLORATION Disruptions during the Tudor the creation of the Protestant Church of England by Henry VIII in the , the return of the nation to Catholicism under Queen Mary in the , and the restoration of Protestantism under Queen England with little energy for overseas projects . More important , England lacked the resources for such endeavors . Nonetheless , English monarchs carefully monitored developments in the new Atlantic World and took steps to assert England claim to the Americas . As early as 1497 , Henry VII of England had commissioned John Cabot , an Italian mariner , to explore new lands . Cabot sailed from England that year and made landfall somewhere along the North American coastline . For the next century , English routinely crossed the Atlantic to the rich waters off the North American coast . However , English colonization efforts in the were closer to home , as England devoted its energy to the colonization of Ireland . Queen Elizabeth favored England advance into the Atlantic World , though her main concern was blocking Spain effort to eliminate Protestantism . Indeed , England could not commit to colonization in the Americas as long as Spain appeared ready to invade Ireland or Scotland . Nonetheless , Elizabeth approved of English privateers , sea captains to whom the home government had given permission to raid the enemy at will . These skilled mariners cruised the Caribbean , plundering Spanish ships whenever they could . Each year the English took more than from Spain in this way English privateer Francis Drake made a name for himself when , in 1573 , he looted silver , gold , and pearls worth . Elizabeth did sanction an early attempt at colonization in 1584 , when Sir Walter Raleigh , a favorite of the queen , attempted to establish a colony at Roanoke , an island off the coast of North Carolina . The colony was small , consisting of only 117 people , who suffered a poor relationship with the local , and struggled to survive in their new land ( Figure . Their governor , John White , returned to England in late 1587 to secure more people and supplies , but events conspired to keep him away from Roanoke for three years . By the time he returned in 1590 , the entire colony had vanished . The only trace the colonists left behind was the word Croatoan carved into a fence surrounding the village . Governor White never knew whether the colonists had decamped for nearby Croatoan Island ( now ) or whether some disaster had befallen them all . Roanoke is still called the lost colony . FIGURE In 1588 , a promoter of English colonization named Thomas published A and True Report of the New Found Land of Virginia , which contained many engravings of the native peoples who lived on the Carolina coast in the . This print , The oftheir flame ( 1590 ) by Theodor de , shows the ingenuity and wisdom of the savages of the New World . credit UNC Chapel Hill ) English promoters of colonization pushed its commercial advantages and the religious that

44 Early Globalization The Atlantic World , English colonies would allow the establishment of Protestantism in the Americas . Both arguments struck a chord . In the early , wealthy English merchants and the landed elite began to pool their resources to form joint stock companies . In this novel business arrangement , which was in many ways the precursor to the modern corporation , investors provided the capital for and assumed the risk of a venture in order to reap returns . The companies gained the approval of the English crown to establish colonies , and their investors dreamed of reaping great from the money they put into overseas colonization . The permanent English settlement was established by a joint stock company , the Virginia Company . Named for Elizabeth , the virgin queen , the company gained royal approval to establish a colony on the east coast of North America , and in 1606 , it sent 144 men and boys to the New World . In early 1607 , this group sailed up Chesapeake Bay . Finding a river they called the James in honor of their new king , James , they established a ramshackle settlement and named it Jamestown . Despite serious struggles , the colony survived . Many of Jamestown settlers were desperate men although they came from elite families , they were younger sons who would not inherit their father estates . The Jamestown adventurers believed they would instant wealth in the New World and did not actually expect to have to perform work . Henry Percy , the eighth son of the Earl of , was among them . His account , excerpted below , illustrates the hardships the English confronted in Virginia in 1607 . MY STORY George Percy and the First Months at Jamestown The 144 men and boys who started the Jamestown colony faced many hardships by the end of the winter , only 38 had survived . Disease , hunger , and poor relationships with local natives all contributed to the colony high death toll . George Percy , who served twice as governor of Jamestown , kept records of the colonists months in the colony . These records were later published in London in 1608 . This excerpt is from his account of August and September of 1607 . The fourth day of September died Thomas Jacob Sergeant . The day , there died Benjamin Beast . Our men were destroyed with cruel diseases , as Swellings , Fluxes , Burning Fevers , and by wars , and some departed suddenly , but forthe most part they died of mere famine . There were never Englishmen left in a foreign Country in such misery as we were in this new discovered Virginia . was but a small Can of Barley sod in water , to men a day , our drink cold water taken out of the River , which was at a flood very salty , at a low tide full of slime and , which was the destruction of many of our men . Thus we lived for the space of months in this miserable distress , not having able men to man our Bulwarks upon any occasion . If it had not pleased God to have put a terror in the Savages hearts , we had all perished by those wild and cruel Pagans , being in that weak estate as we were our men night and day groaning in every corner of the Fort most pitiful to hear . If there were any conscience in men , it would make their hearts to bleed to hearthe pitiful murmurings and outcries of our sick men without relief , every night and day , for the space of six weeks , some departing out of the World , many times three or four in a night in the morning , their bodies trailed out of their Cabins like Dogs to be buried . In this sort did I see the mortality of diverse of our soa ked Accordingto George Percy account , what were the major problems the Jamestown settlers encountered ?

What kept the colony from complete destruction ?

By any measure , England came late to the race to colonize . As Jamestown limped along in the , the Spanish Empire extended around the globe and grew rich from its global colonial project . Yet the English persisted , and for this reason the Jamestown settlement has a special place in history as the permanent English colony in what later became the United States . Access for free at .

After Jamestown founding , English io Jamestown foundered in a storm and landed on Challenges to Spain Supremacy 45 of the New World accelerated . In 1609 , a ship bound for Bermuda . Some believe this incident helped inspire Shakespeare 1611 play The Tempest . The admiral of the ship , George Somers , claimed the island for the English crown . The English also began to colonize small islands in the Caribbean , an incursion into the Spanish American empire . They established on small islands such as Christopher ( 1624 ) Barbados ( 1627 ) 1628 ) 1632 ) and Antigua ( 1632 ) From the start , the English West Indies had a commercial orientation , for these islands produced cash crops tobacco and then sugar . Very quickly , by English colonies because of the sugar produced enslaved people , and it became a model for ot , Barbados had become one of the most important there . Barbados was the English colony dependent on English slave societies on the American mainland . These differed radically from England itself , where slavery was not practiced . English Puritans also began to colonize the Ame migrants dreamed of creating communities in the and . These intensely religious reformed Protestantism where the corruption of England would be eliminated . One of the groups of Puritans to move to North America , known as Pilgrims and led by William Bradford , had originally left England ol ive in the Netherlands . Fearing their children were losing their English identity among the Dutch , however , they sailed for North America in 1620 to settle at Plymouth , the English settlement in New England . The Pilgrims differed from other Puritans in their insistence on separating from what they saw as the corrupt Church of England . For this reason , Pilgrims are known as Separatists . Like Jamestown , Plymouth occupies an iconic migrants who crossed the Atlantic aboard the Ma narrative of the founding of the country . Their agreement whereby the English voluntarily agre an expression of democratic spirit because of th work together In 1630 , a much larger England and founded the Massachusetts Bay Co new life in the rocky soils and cold climates In comparison to Catholic Spain , however , Protest early seventeenth century , with only a few never found treasure equal to that of the Aztec ace in American national memory . The tale of the 102 their struggle for survival is a ory includes the signing of the Compact , a written ed to help each other . Some interpret this 1620 document as cooperative and inclusive nature of the agreement to live and of Puritans left England to escape conformity to the Church of ony . In the following years , thousands more arrived to create a ew England . ant England remained a very weak imperial player in the colonies in the Americas in the early . The English of , and England did not quickly grow rich from its small American outposts . The English colonies also differed from each other Barbados and Virginia had a decidedly commercial orientation from the star , while the Puritan colonies of New England were intensely religious at their inception . All English settlements in America , however , marked the increasingly important role of England in the Atlantic World . FRENCH EXPLORATION Spanish exploits in the New World whetted the a of other imperial powers , including France . Like Spain , France was a Catholic nation and committed to expanding Catholicism around the globe . In the early sixteenth century , it joined the race to . Navigator Jacques Cartier claimed ore the New World and exploit the resources of the Western northern North America for France , naming the area New France . From 1534 to 1541 , he made three voyages of discovery on the Gulf of Lawrence and the Lawrence River . Like other explorers , Cartier made exaggerated claims of mineral wealth in America , but he was unable to send great riches back to France . Due to resistance from the native peoples as well as his own lack of planning , he could not establish a permanent settlement in North America . Explorer Samuel de occupies a speci establishing the French presence in the New Wo al place in the history of the Atlantic World for his role in . explored the Caribbean in 1601 and then the coast of New England in 1603 before traveling farther north . In 1608 he founded Quebec , and he made

46 Early Globalization The Atlantic World , numerous Atlantic crossings as he worked tirelessly to promote New France . Unlike other imperial powers , especially good relationships with native peoples , paving the way for French exploration further into the continent around the Great Lakes , around Hudson Bay , and eventually to the Mississippi . made an alliance with the Huron confederacy and the and agreed to with them against their enemy , the Iroquois ( Figure . FIGURE In this engraving , titled Defeat of the Iroquois and based on a drawing by explorer Samuel de , is shown on the side of the Huron and against the Iroquois . He portrays himself in the middle of the battle , a gun , while the native people around him shoot arrows at each other . What does this engraving suggest about the impact of European exploration and settlement on the Americas ?

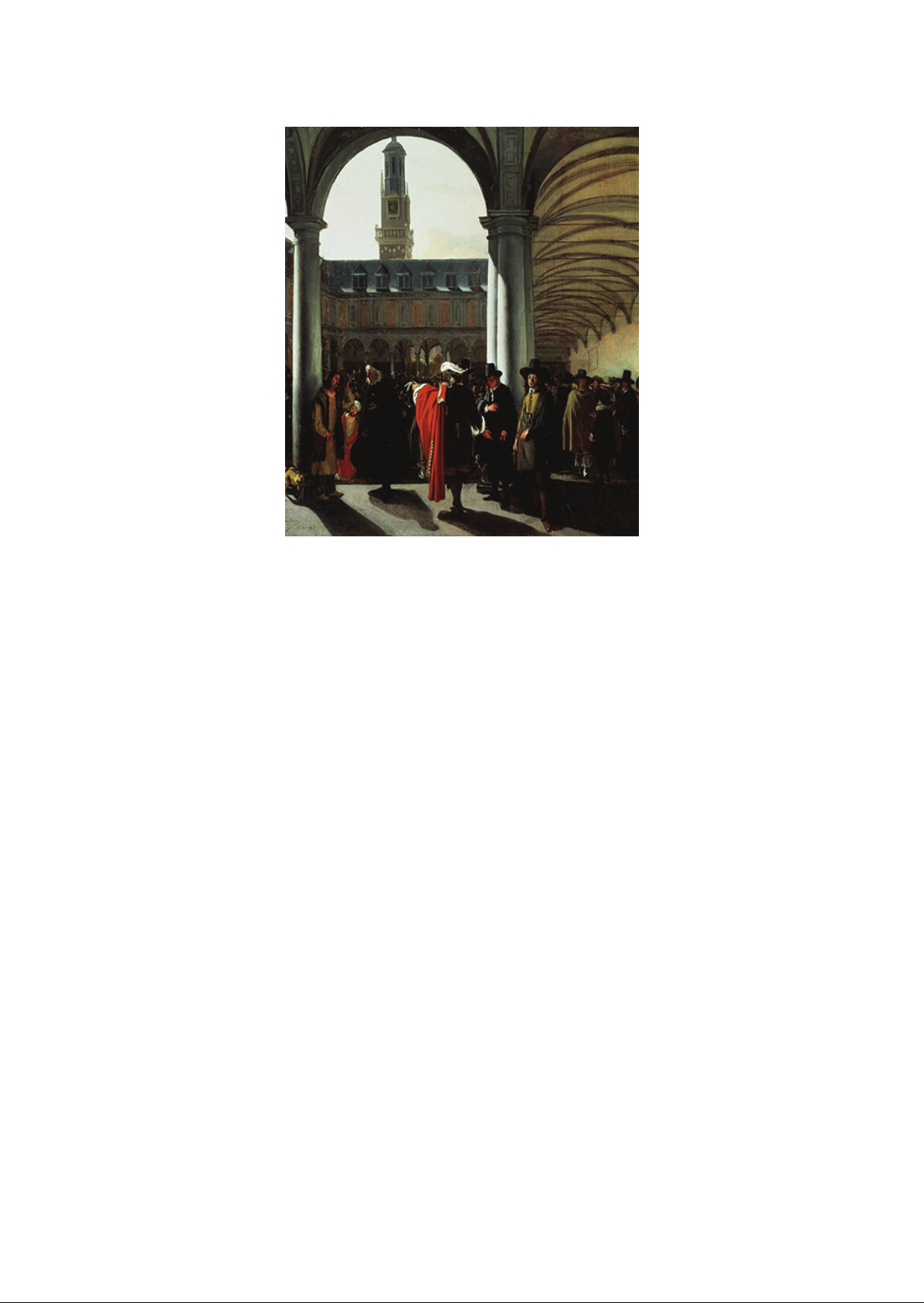

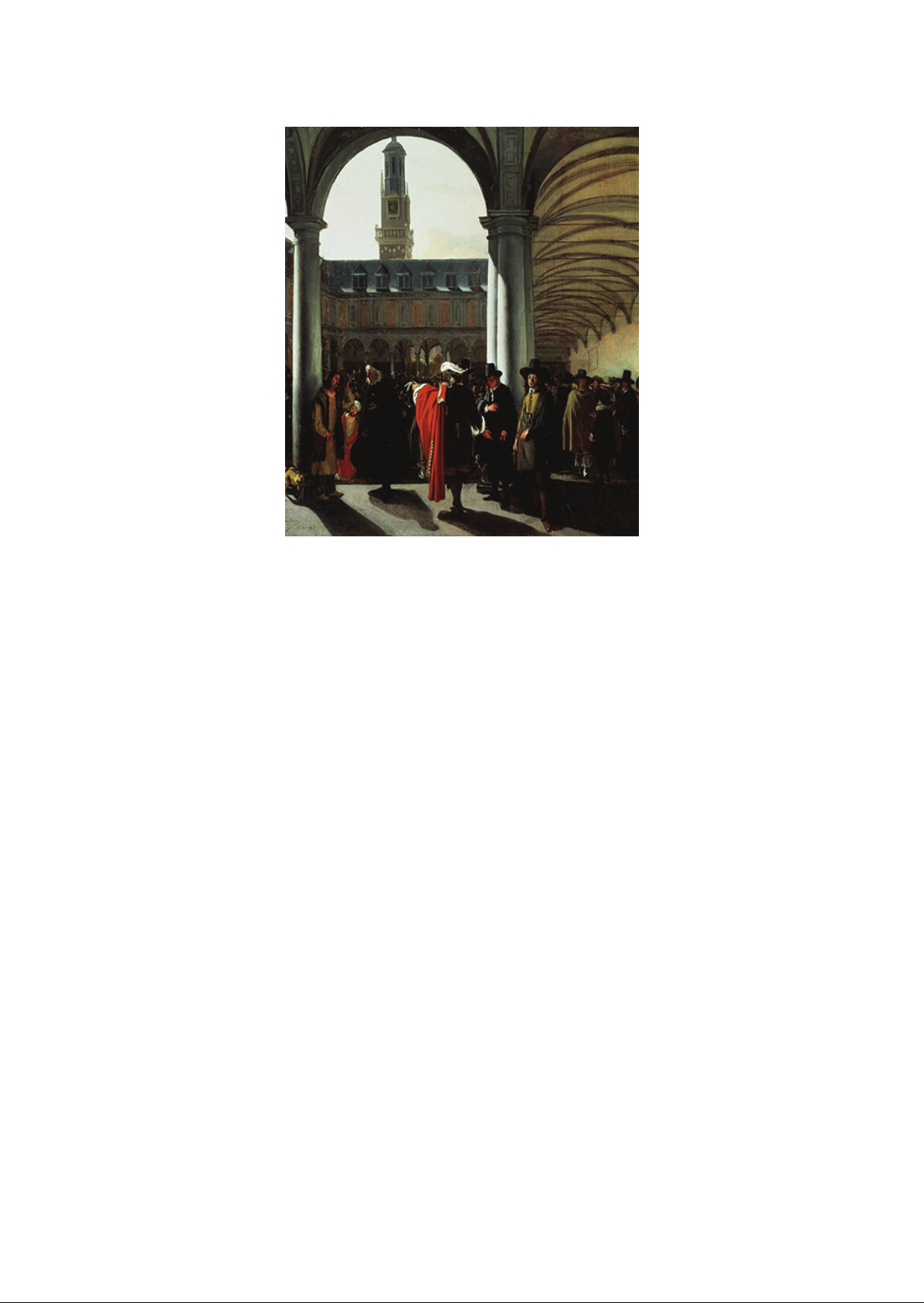

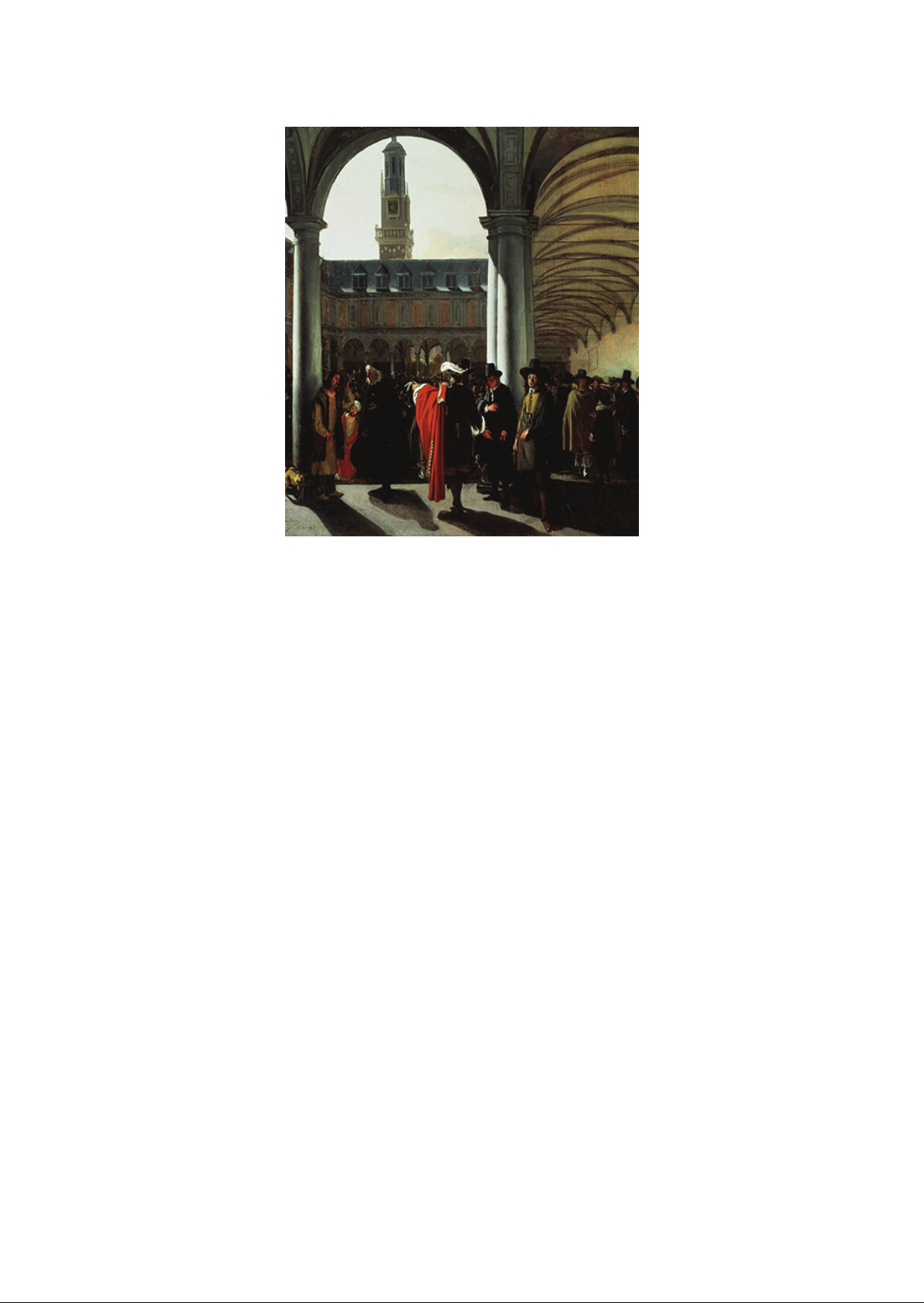

The French were primarily interested in establishing commercially viable colonial outposts , and to that end , they created extensive trading networks in New France . These networks relied on native hunters to harvest furs , especially beaver pelts , and to exchange these items for French glass beads and other trade goods . French fashion at the time favored hats trimmed in beaver fur , so French traders had a ready market for their North American goods . The French also dreamed of replicating the wealth of Spain by colonizing the tropical zones . After Spanish control of the Caribbean began to weaken , the French turned their attention to small islands in the West Indies , and by 1635 they had colonized two , and Martinique . Though it lagged far behind Spain , France now boasted its own West Indian colonies . Both islands became lucrative sugar plantation sites that turned a for French planters by relying on African slave labor . CLICK AND EXPLORE To see how cartographers throughout history documented the exploration of the Atlantic World , browse the hundreds of digitized historical maps that make up the collection American Shores Maps of the Middle Atlantic Region to 1850 ( at the New York Public Library . DUTCH COLONIZATION Dutch entrance into the Atlantic World is part of the larger story of religious and imperial in the early modern era . In the , one of the major Protestant reform movements , had found adherents in the northern provinces of the Spanish Netherlands . During the sixteenth century , these provinces began a long struggle to achieve independence from Catholic Spain . Established in 1581 but not recognized as independent by Spain until 1648 , the Dutch Republic , or Holland , quickly made itself a powerful force in the race for Atlantic colonies and wealth . The Dutch distinguished themselves as commercial leaders in the seventeenth century Figure , and their mode of colonization relied on powerful corporations the Dutch East India Company , chartered in 1602 to trade in Asia , and the Dutch West India Company , established in 1621 to Access for free at .

New Worlds in the Americas Labor , Commerce , and the Columbian Exchange 47 colonize and trade in the Americas . FIGURE Amsterdam was the richest city in the world in the . In Courtyard of the Exchange in Amsterdam , a 1653 painting by Emanuel de Witt , merchants involved in the global trade eagerly attend to news of shipping and the prices of commodities . While employed by the Dutch East India Company in 1609 , the English sea captain Henry Hudson explored New York Harbor and the river that now bears his name . Like many explorers of the time , Hudson was actually seeking a northwest passage to Asia and its wealth , but the ample furs harvested from the region he explored , especially the coveted beaver pelts , provided a reason to claim it for the Netherlands . The Dutch named their colony New Netherlands , and it served as a outpost for the expanding and powerful Dutch West India Company . With headquarters in New Amsterdam on the island of Manhattan , the Dutch set up several regional trading posts , including one at Fort for the royal Dutch House of Albany . The color orange remains to the Dutch , having become particularly associated with William of Orange , Protestantism , and the Glorious Revolution of 1688 . A brisk trade in furs with local Algonquian and Iroquois peoples brought the Dutch and native peoples together in a commercial network that extended throughout the Hudson River Valley and beyond . The Dutch West India Company in turn established colonies on Aruba , and Curacao , Martin , and Saba . With their outposts in New Netherlands and the Caribbean , the Dutch had established themselves in the seventeenth century as a commercially powerful rival to Spain . Amsterdam became a trade hub for all the Atlantic World . New Worlds in the Americas Labor , Commerce , and the Columbian Exchange LEARNING OBJECTIVES By the end ofthis section , you will be able to Describe how Europeans solved their labor problems Describe the theory of mercantilism and the process of Analyze the effects of the Columbian Exchange European promoters of colonization claimed the Americas with a wealth of treasures . Burnishing national glory and honor became entwined with carving out colonies , and no nation wanted to be left behind .

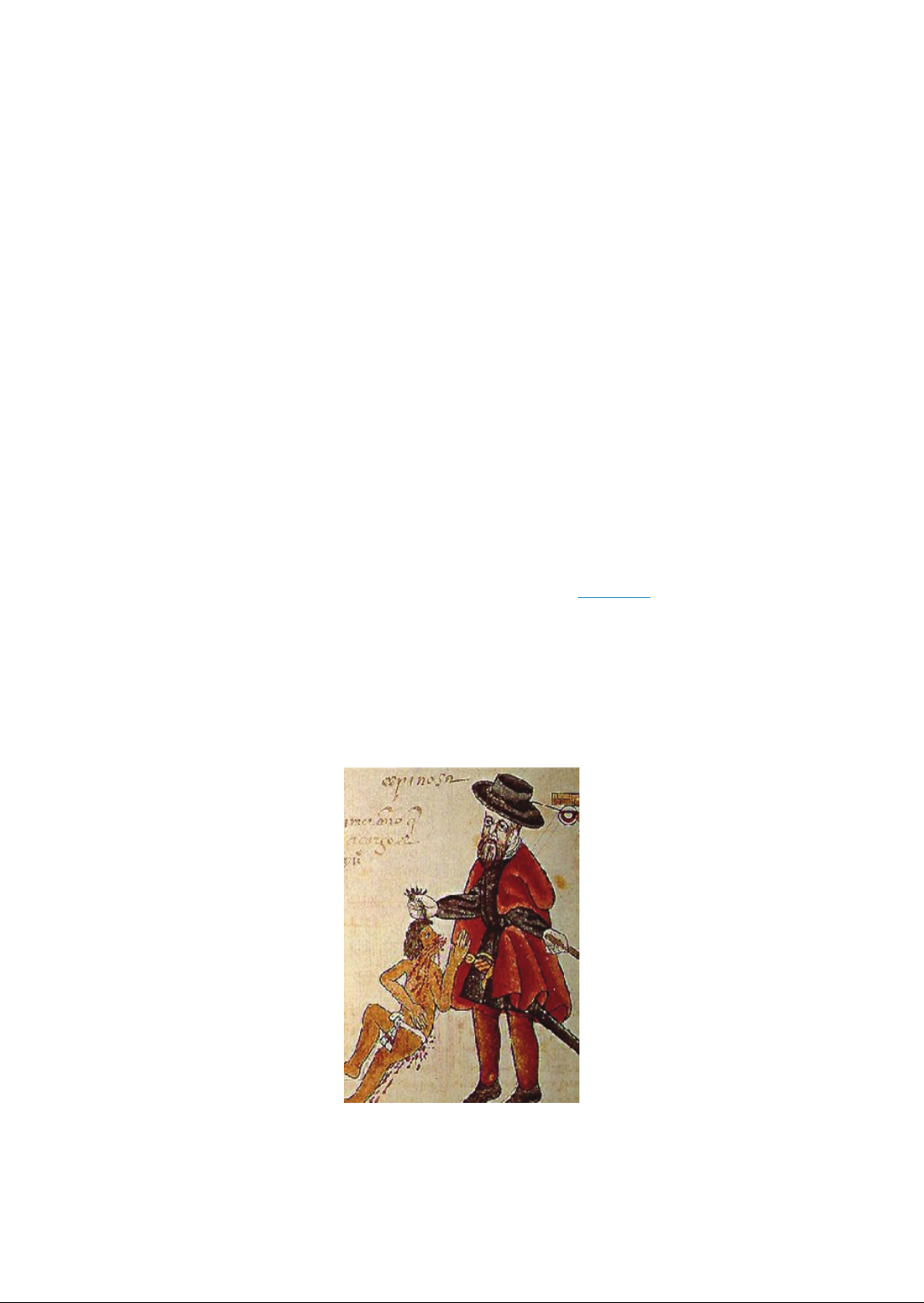

48 Early The Atlantic World , However , the realities of life in the , exploitation , and particularly the need for soon driving the practice of slavery and forced labor . Everywhere in America a stark contrast existed between freedom and slavery . The Columbian Exchange , in which Europeans transported plants , animals , and diseases across the Atlantic in both directions , also left a lasting impression on the Americas . LABOR SYSTEMS Physical work the , build villages , process raw a necessity for maintaining a society . During the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries , humans could derive power only from the wind , water , animals , or other humans . Everywhere in the Americas , a crushing demand for labor bedeviled Europeans because there were not enough colonists to perform the work necessary to keep the colonies going . Spain granted rights to native conquistadors who could prove their service to the crown . This system the Spanish view of colonization the king rewarded successful conquistadors who expanded the empire . Some native peoples who had sided with the conquistadors , like the , also gained , the woman who helped Cortes defeat the , was granted one . The Spanish believed native peoples would work for them by right of conquest , and , in return , the Spanish would bring them Catholicism . In theory the relationship consisted of reciprocal obligations , but in practice the Spaniards ruthlessly exploited it , seeing native people as little more than beasts of burden . Convinced of their right to the land and its peoples , they sought both to control native labor and to impose what they viewed as correct religious beliefs upon the land inhabitants . Native peoples everywhere resisted both the labor obligations and the effort to change their ancient belief systems . Indeed , many retained their religion or incorporated only the parts of Catholicism that made sense to them . The system of was accompanied by a great deal of violence ( Figure . One Spaniard , Bartolome de Las Casas , denounced the brutality of Spanish rule . A Dominican friar , Las Casas had been one of the earliest Spanish settlers in the Spanish West Indies . In his early life in the Americas , he enslaved Native people and was the recipient of an encomienda . However , after witnessing the savagery with which ( recipients of ) treated the native people , he reversed his views . In 1515 , Las Casas released his enslaved natives , gave up his encomienda , and began to advocate for humane treatment of native peoples . He lobbied for new legislation , eventually known as the New Laws , which would eliminate slavery and the encomienda system . FIGURE In this startling image from the Codex ( a book written and drawn by native Mesoamericans ) a Spaniard is shown hair of a bleeding , severely injured Native . The drawing was part of a complaint about Spanish abuses of their . Access for free at .

New Worlds in the Americas Labor , Commerce , and the Columbian Exchange 49 Las Casas writing about the Spaniards treatment of Native people helped inspire the Black Legend , the idea that the Spanish were bloodthirsty conquerors with no regard for human life . Perhaps not surprisingly , those who held this view of the Spanish were Spain imperial rivals . English writers and others seized on the idea of Spain ruthlessness to support their own colonization projects . By demonizing the Spanish , they their own efforts as more humane . All European colonizers , however , shared a disregard for Native peoples . MY STORY de Las Casas on the Mistreatment of Native Peoples de Las Casas A of the Destruction of the Indies , written in 1542 and published ten years later , detailed for Prince Philip II of Spain how Spanish colonists had been mistreating natives . Into and gentle sheep , endowed by their Maker and Creator with all the qualities aforesaid , did creep the Spaniards , who no sooner had knowledge of these people than they became like wolves and tigers and lions who have gone many days without food or nourishment . And no otherthing have they done for forty years until this day , and still today see to do , but dismember , slay , perturb , afflict , torment , and destroy the Native Americans by all manner of and divers and most singular manners such as never before seen or read or heard few of which shall be recounted below , and they do this to such a degree that on the Island of , ofthe above three millions souls that we once saw , today there be no more than two hundred of those native people remaining . Two principal and general customs have been employed by those , Christians , who have passed this way , in extirpating and striking from the face of the earth those suffering nations . The first being unjust , cruel , bloody , and tyrannical warfare . The having slain all those who might yearn toward or suspire after or think of freedom , or consider escaping from the torments that they are made to suffer , by which I mean all the lords and adult males , for it is the Spaniards custom in their wars to allow only young boys and females to to oppress them with the hardest , harshest , and most heinous bondage to which men or beasts might ever be bound How might these writings have been used to promote the black legend against Spain as well as subsequent English exploration and colonization ?

Native peoples were not the only source of cheap labor in the Americas by the middle of the sixteenth century , A ricans formed an important element of the labor landscape , producing the cash crops of sugar and tobacco for European markets . Europeans viewed Africans as , which they used as a for enslavement . Denied control over their lives , enslaved people endured horrendous conditions . At every , they resisted enslavement , and their resistance was met with violence . Indeed , physical , mental , and sexual violence formed a key strategy among European slaveholders in their effort to assert mastery and impose their will . The Portuguese led the way in the evolving transport of captive enslaved people across the A slave factories on the west coast , like Castle in , served as holding pens for enslaved people brought from Africa interior . In time , other European imperial powers would follow in the footsteps of the Portuguese by constructing similar outposts on the coast of West Africa . Portuguese traded or sold enslaved people to Spanish , Dutch , and English colonists in the Americas , particularly in South America and the Caribbean , where sugar was a primary export . Thousands of enslaved A ricans found themselves growing , harvesting , and processing sugarcane in an arduous routine of physical . Enslaved people had to cut the long cane stalks by hand and then bring them to a mill , where the cane juice was extracted . They boiled the extracted cane juice down to a brown , crystalline sugar , which then had to be cured in special curing houses to have the molasses drained from it . The result was sugar , while the le molasses could be distilled into rum . Every step was and often dangerous .

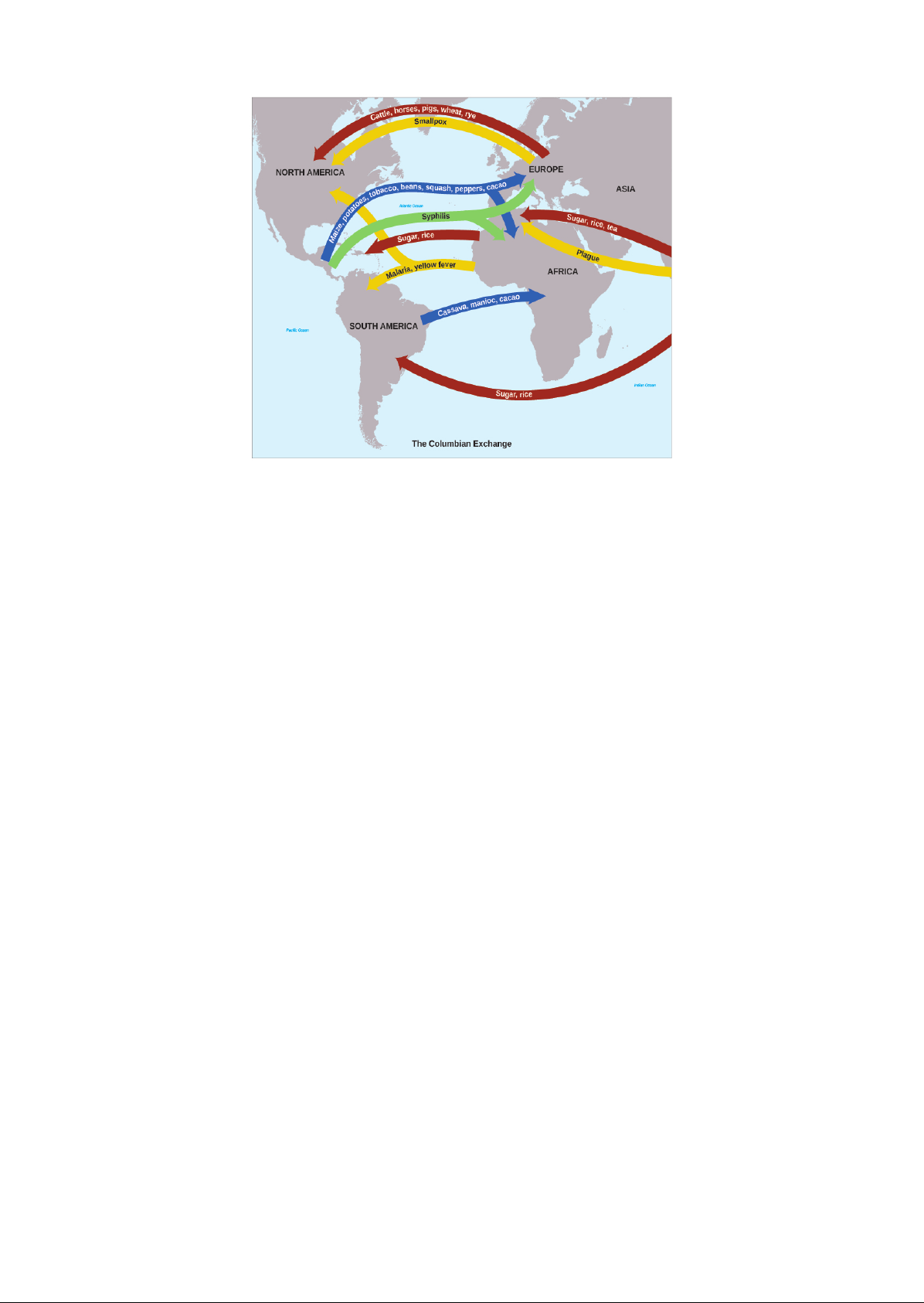

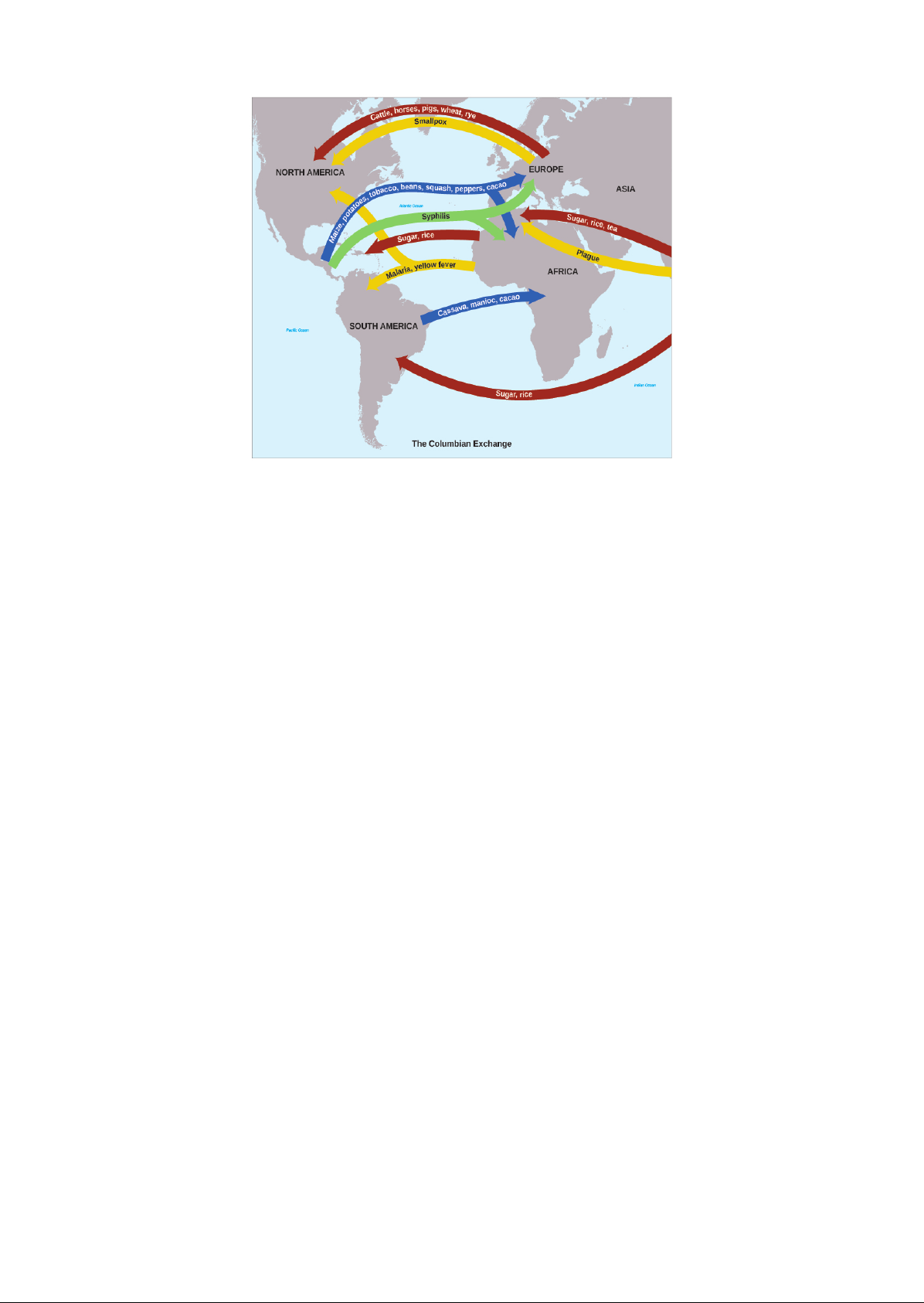

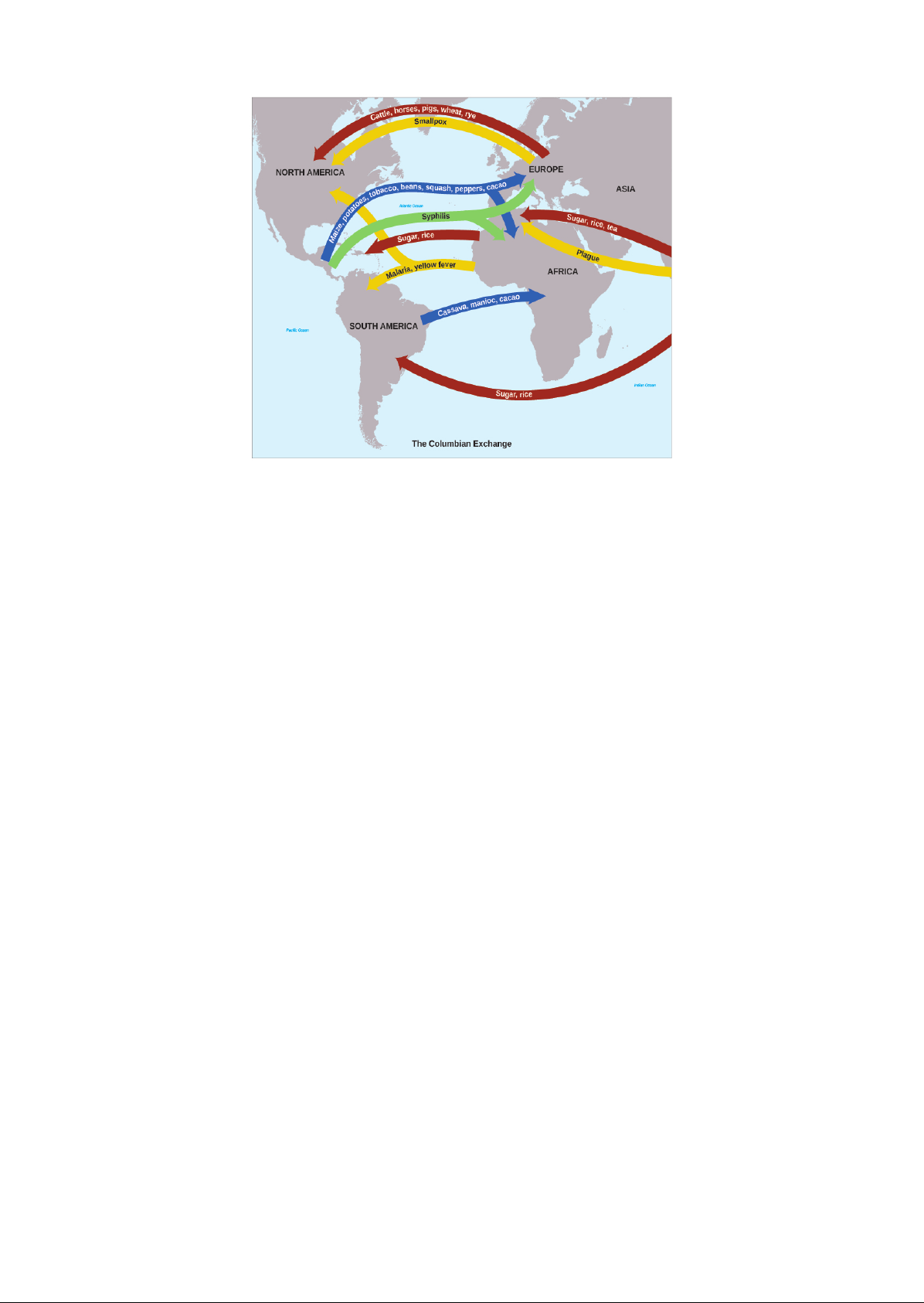

50 Early The Atlantic World , Las Casas estimated that by 1550 , there were thousand enslaved people on . However , it is a mistake to assume that during the very early years of European exploration all Africans came to America as captives some were free men who took part in expeditions , for example , serving as conquistadors alongside in his assault on . Nonetheless , African slavery was one of the most tragic outcomes in the emerging Atlantic World . CLICK AND EXPLORE Browse the collection Africans in America Part ( to see information and primary sources for the period 1450 through 1750 . COMMERCE IN THE NEW WORLD The economic philosophy of mercantilism shaped European perceptions of wealth from the to the late . Mercantilism held that only a limited amount of wealth , as measured in gold and silver bullion , existed in the world . In order to gain power , nations had to amass wealth by mining these precious raw materials from their colonial possessions . During the age of European exploration , nations employed conquest , colonization , and trade as ways to increase their share of the bounty of the New World . did not believe in free trade , arguing instead that the nation should control trade to create wealth . In this view , colonies existed to strengthen the colonizing nation . argued against allowing their nations to trade freely with other nations . Spain mercantilist ideas guided its economic policy . Every year , enslaved laborers or native workers loaded shipments of gold and silver aboard Spanish treasure that sailed from Cuba for Spain . These ships groaned under the sheer weight of bullion , for the Spanish had found huge caches of silver and gold in the New World . In South America , for example , Spaniards discovered rich veins of silver ore in the mountain called and founded a settlement of the same name there . Throughout the sixteenth century , was a boom town , attracting settlers from many nations as well as native people from many different cultures . Colonial mercantilism , which was basically a set of protectionist policies designed to the nation , relied on several factors colonies rich in raw materials , cheap labor , colonial loyalty to the home government , and control of the shipping trade . Under this system , the colonies sent their raw materials , harvested by enslaved laborers or native workers , back to their mother country . The mother country sent back materials of all sorts textiles , tools , clothing . The colonists could purchase these goods their mother country trade with other countries was forbidden . The and early also introduced the process of to the New World . American silver , tobacco , and other items , which were used by native peoples for ritual purposes , became European commodities with a monetary value that could be bought and sold . Before the arrival of the Spanish , for example , the Inca people of the Andes consumed chicha , a corn beer , for ritual purposes only . When the Spanish discovered chicha , they bought and traded for it , turning it into a commodity instead of a ritual substance . thus recast native economies and spurred the process of early commercial capitalism . New World resources , from plants to animal pelts , held the promise of wealth for European imperial powers . THE COLUMBIAN EXCHANGE As Europeans traversed the Atlantic , they brought with them plants , animals , and diseases that changed lives and landscapes on both sides of the ocean . These exchanges between the Americas and are known collectively as the Columbian Exchange Figure . Access for free at .

New Worlds in the Americas Labor , Commerce , and the Columbian Exchange 51 me . miss , pugs , wheat , Smallpox NORTH AMERICA EUROPE SOUTH AMERICA The Exchange FIGURE With European exploration and settlement of the New World , goods and diseases began Atlantic Ocean in both directions . This Columbian Exchange soon had global implications . Of all the commodities in the Atlantic World , sugar proved to be the most important . Indeed , sugar carried the same economic importance as oil does today . European rivals raced to create sugar plantations in the Americas and fought wars for control of some of the best sugar production areas . Although sugar was available in the Old World , Europe harsher climate made sugarcane to grow , and it was not plentiful . Columbus brought sugar to in 1493 , and the new crop was growing there by the end of the 14905 . By the decades of the , the Spanish were building sugar mills on the island . Over the next century of colonization , Caribbean islands and most other tropical areas became centers of sugar production . Though of secondary importance to sugar , tobacco achieved great value for Europeans as a cash crop as well . Native peoples had been growing it for medicinal and ritual purposes for centuries before European contact , smoking it in pipes or powdering it to use as snuff . They believed tobacco could improve concentration and enhance wisdom . To some , its use meant achieving an entranced , altered , or divine state entering a spiritual place . Tobacco was unknown in Europe before 1492 , and it carried a negative stigma at . The early Spanish explorers considered natives use of tobacco to be proof of their savagery and , because of the and smoke produced in the consumption of tobacco , evidence of the Devil sway in the New World . Gradually , however , European colonists became accustomed to and even took up the habit of smoking , and they brought it across the Atlantic . As did the Native Americans , Europeans ascribed medicinal properties to tobacco , claiming that it could cure headaches and skin irritations . Even so , Europeans did not import tobacco in great quantities until the 15905 . At that time , it became the first truly global commodity English , French , Dutch , Spanish , and Portuguese colonists all grew it for the world market . Native peoples also introduced Europeans to chocolate , made from cacao seeds and used by the Aztec in as currency . Mesoamerican Natives consumed unsweetened chocolate in a drink with chili peppers , vanilla , and a spice called achiote . This chocolate part of ritual ceremonies like marriage and an everyday item for those who could afford it . Chocolate contains theobromine , a stimulant , which may be why native people believed it brought them closer to the sacred world . Spaniards in the New World considered drinking chocolate a vile practice one called chocolate the vomit . In time , however , they introduced the beverage to Spain . At first , chocolate was available only in the Spanish court , where the elite mixed it with sugar and other spices . Later , as its availability spread , chocolate gained a reputation as a love potion .

52 Early The Atlantic World , CLICK AND EXPLORE Visit Nature Transformed ( for a collection of scholarly essays on the environment in American history . The crossing of the Atlantic by plants like cacao and tobacco illustrates the ways in which the discovery of the New World changed the habits and behaviors of Europeans . Europeans changed the New World in turn , not least by bringing World animals to the Americas . On his second voyage , Christopher Columbus brought pigs , horses , cows , and chickens to the islands of the Caribbean . Later explorers followed suit , introducing new animals or reintroducing ones that had died out ( like horses ) With less vulnerability to disease , these animals often fared better tian humans in their new home , thriving both in the wild and in domestication . Europeans ered New World animals as well . Because European Christians understood the world as a place of warfare be ween God and Satan , many believed the Americas , which lacked Christianity , were home to the Devil and his minions . The exotic , sometimes bizarre , appearances and habits of animals in the Americas that were previously unknown to Europeans , such as manatees , sloths , and poisonous snakes , this association . Over time , however , they began to rely more on observation of the natural world than solely on scripture . This seeing the Bible as the source of all received wisdom to trusting observation or one of the major outcomes of the era of early globalization . Travelers between he Americas , Africa , and Europe also included microbes silent , invisible life forms that had profound and devastating consequences . Native peoples had no immunity to diseases from across the Atlantic , to which had never been exposed . European explorers unwittingly brought with them chickenpox , measles , mumps , and smallpox , which ravaged native peoples despite their attempts to treat the diseases , decimating some populations and wholly destroying others ( Figure . FIGURE This Aztec drawing shows the suffering of a typical victim of smallpox . Smallpox and other contagious diseases brought by European explorers decimated Native populations in the Americas . In eastern North America , some native peoples interpreted death from disease as a hostile act . Some groups , including the Iroquois , engaged in raids or mourning wars , taking enemy prisoners in order to assuage their grief and replace the departed . In a special ritual , the prisoners were the identity of a dead adopted by the bereaved family to take the place of their dead . As the toll from disease rose , mourning wars and expanded . Access for free at .

Key Terms 53 Key Terms Black Legend Spain reputation as bloodthirsty conquistadors a branch of started by John Calvin , emphasizing human powerlessness before an omniscient God and stressing the idea of predestination Columbian Exchange he movement of plants , animals , and diseases across the Atlantic due to European exploration of the Americas the transformation of example , an item of ritual a commodity with monetary value encomienda legal righ to native labor as granted by the Spanish crown the island in the Caribbean , Haiti and Dominican Republic , where Columbus landed on his voyage to the Americas and established a Spanish colony indulgences for purchase that absolved sinners of their errant behavior joint stock company a business entity in which investors provide the capital and assume the risk in order to reap returns mercantilism the protectionist economic principle that nations should control trade with their colonies to ensure a favorable ba ance of trade mourning wars raids or wars that tribes waged in eastern North America in order to replace members lost to smallpox and other diseases Pilgrims Separatists , led by William Bradford , who established the English settlement in New England privateers sea captains to whom the British government had given permission to raid Spanish ships at will de proof of merit a letter written by a Spanish explorer to the crown to gain royal patronage Protestant Reformation the schism in Catholicism that began with Martin Luther and John Calvin in the early sixteenth century Puritans a group of religious reformers in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries who wanted to purify the Church of England by ridding it of practices associated with the Catholic Church and advocating greater purity of doctrine and worship Roanoke the English colony in Virginia , which mysteriously disappeared sometime between 1587 and 1590 Separatists a faction of Puritans who advocated complete separation from the Church of England smallpox a disease that Europeans accidentally brought to the New World , killing millions of Native Americans , who had no immunity to the disease sugarcane one of the primary crops of the Americas , which required a tremendous amount of labor to cultivate Summary Portuguese Exploration and Spanish Conquest Although Portugal opened the door to exploration of the Atlantic World , Spanish explorers quickly made inroads into the Americas . Spurred by Christopher Columbus glowing reports of the riches to be found in the New World , throngs of Spanish conquistadors set off to and conquer new lands . They accomplished this through a combination of military strength and strategic alliances with native peoples . Spanish rulers Ferdinand and Isabella promoted the acquisition of these new lands in order to strengthen and glorify their own empire . As Spain empire expanded and riches in from the Americas , the Spanish experienced a golden age of art and literature . Religious Upheavals in the Developing Atlantic World The sixteenth century witnessed a new challenge to the powerful Catholic Church . The reformist doctrines of Martin Luther and John Calvin attracted many people with Catholicism , and Protestantism spread

54 Review Questions across northern Europe , spawning many subgroups with conflicting beliefs . Spain led the charge against Protestantism , leading to decades of undeclared religious wars between Spain and England , and religious intolerance and violence characterized much of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries . Despite the efforts of the Catholic Church and Catholic nations , however , Protestantism had taken hold by 1600 . Challenges to Spain Supremacy By the beginning of the seventeenth century , Spain , France , and the Dutch each established an Atlantic presence , with greater or lesser success , in the race for imperial power . None of the new colonies , all in the eastern part of North America , could match the Spanish possessions for gold and silver resources . Nonetheless , their presence in the New World helped these nations establish claims that they hoped could halt the runaway growth of Spain Catholic empire . English colonists in Virginia suffered greatly , expecting riches to fall into their hands and reality a harsh blow . However , the colony at Jamestown survived , and the output of England islands in the West Indies soon grew to be an important source of income for the country . New France and New Netherlands were modest colonial holdings in the northeast of the continent , but these colonies thriving fur trade with native peoples , and their alliances with those peoples , helped to create the foundation for later in the global balance of power . New Worlds in the Americas Labor , Commerce , and the Columbian Exchange In the minds of European rulers , colonies existed to create wealth for imperial powers . Guided by mercantilist ideas , European rulers and investors hoped enrich their own nations and themselves , in order to gain the greatest share of what was believed to be a limited amount of wealth . In their own individual quest for riches and preeminence , European colonizers who traveled to the Americas blazed new and disturbing paths , such as the encomienda system of forced labor and tie enslavement of tens of thousands of Africans . All Native inhabitants of the Americas who came into contact with Europeans found their worlds turned upside down as the new arrivals introduced their re and ideas about property and goods . Europeans gained new foods , plants , and animals in the Exchange , turning whatever they could into a commodity to be bought and sold , and Native peoples were introduced to diseases that nearly destroyed them . At every turn , however , Native Americans placed limits on European colonization and resisted the newcomers ways . Review Questions . Which country initiated the era of Atlantic exploration ?

Spain England . Which country established the colonies in the Americas ?

England . Spain he Netherlands . Where did Christopher Columbus land ?

he Bahamas Mexico . Why did the authors of de choose to write in the way that they did ?

What should we consider when we interpret these documents today ?

Access for free at .

Review Questions 55 . Where did the Protestant Reformation begin ?

A . Northern Europe Spain England he American colonies . Wha was the chief goal of the Puritans ?

achieve a lasting peace with the Catholic nations of Spain and France eliminate any traces of Catholicism from the Church of England assist Henry VIII in his quest for an annulment to his marriage create a hierarchy within the Church of England modeled on that of the Catholic Church . Wha reforms to the Catholic Church did Martin Luther and John Calvin call for ?

Why did England make stronger attempts to colonize the New World before the late sixteenth to early seventeenth century ?

English attention was turned to internal struggles and the encroaching Catholic menace to Scotland and Ireland . The English monarchy did not want to declare direct war on Spain by attempting to colonize the Americas . The English military was occupied in battling for control of New Netherlands . The English crown refused to fund colonial expeditions . What was the main goal of the French in colonizing the Americas ?

establishing a colony with French subjects trading , especially for furs gaining control of shipping lanes spreading Catholicism among native peoples 10 . What were some of the main differences among the colonies ?

11 . How could Spaniards obtain ?

by serving the Spanish crown by buying them from other Spaniards by buying them from native chiefs by inheriting them 12 . Which of the following best describes the Columbian Exchange ?

the letters Columbus and other conquistadors exchanged with the Spanish crown an exchange of plants , animals , and diseases between Europe and the Americas a form of trade between the Spanish and natives the way in which explorers exchanged information about new lands to conquer 13 . Why did diseases like smallpox affect Native Americans so badly ?

A . Native Americans were less robust than Europeans . Europeans deliberately infected Native Americans . Native Americans had no immunity to European diseases . Conditions in the Americas were so harsh that Native Americans and Europeans alike were devastated by disease .

56 Critical Thinking Questions Critical Thinking Questions 14 . 15 . 16 . 17 . 18 . What were the consequences of the religious upheavals of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries ?

What types of labor systems were used in the Americas ?

Did systems of unfree labor serve more than an economic function ?

What is meant by the Columbian Exchange ?

Who was affected the most by the exchange ?

What were the various goals of the colonial European powers in the expansion of their empires ?

To what extent were they able to achieve these goals ?

Where did they fail ?

On the whole , what was the impact of early European explorations on the New World ?

What was the impact of the New World on Europeans ?

Access for free at .