Brother, Can You Spare a Dime_ The Great Depression, 1929-1932

Explore the Brother, Can You Spare a Dime_ The Great Depression, 1929-1932 study material pdf and utilize it for learning all the covered concepts as it always helps in improving the conceptual knowledge.

Brother, Can You Spare a Dime_ The Great Depression, 1929-1932 PDF Download

Brother , Can You Spare a Dime ?

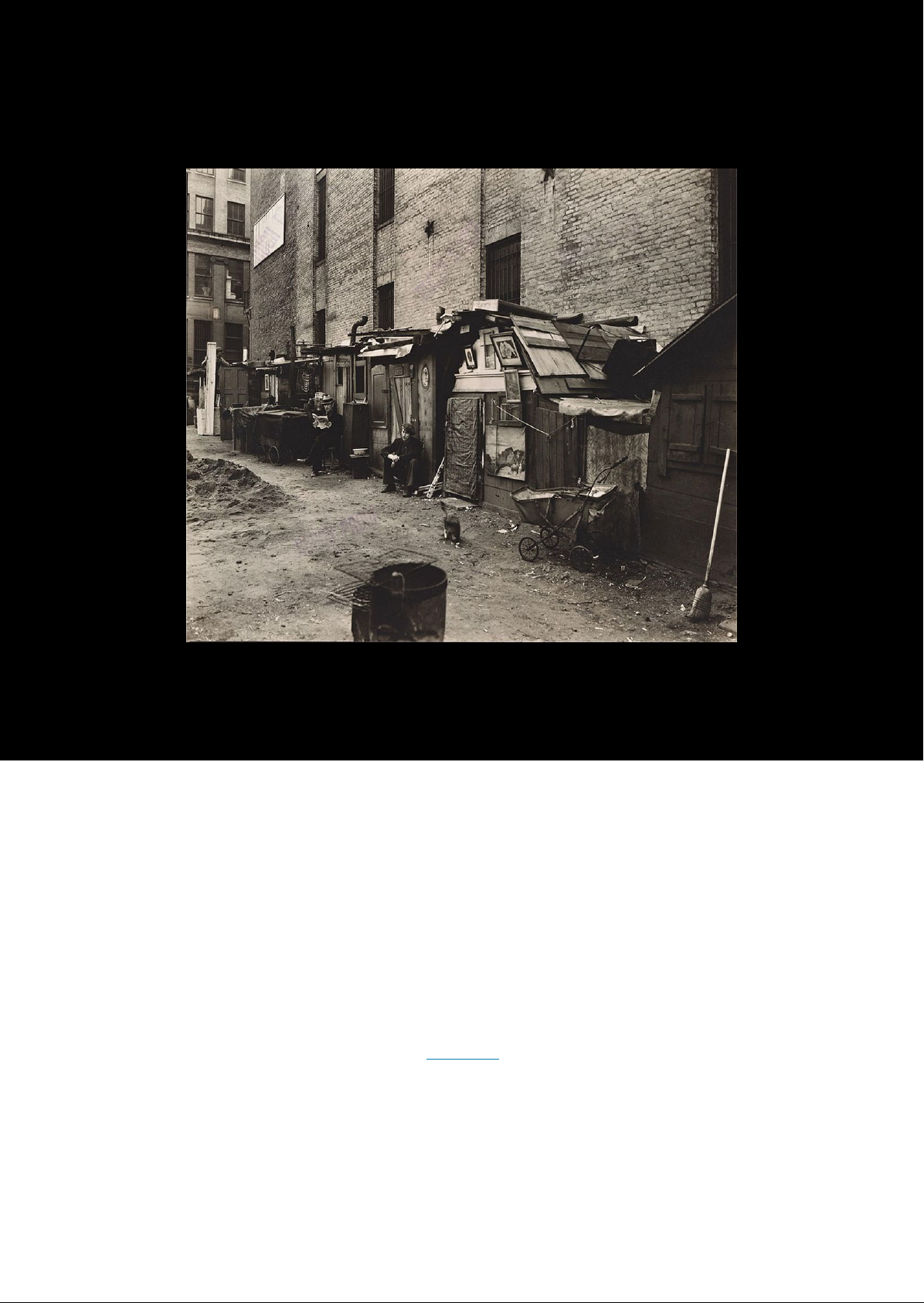

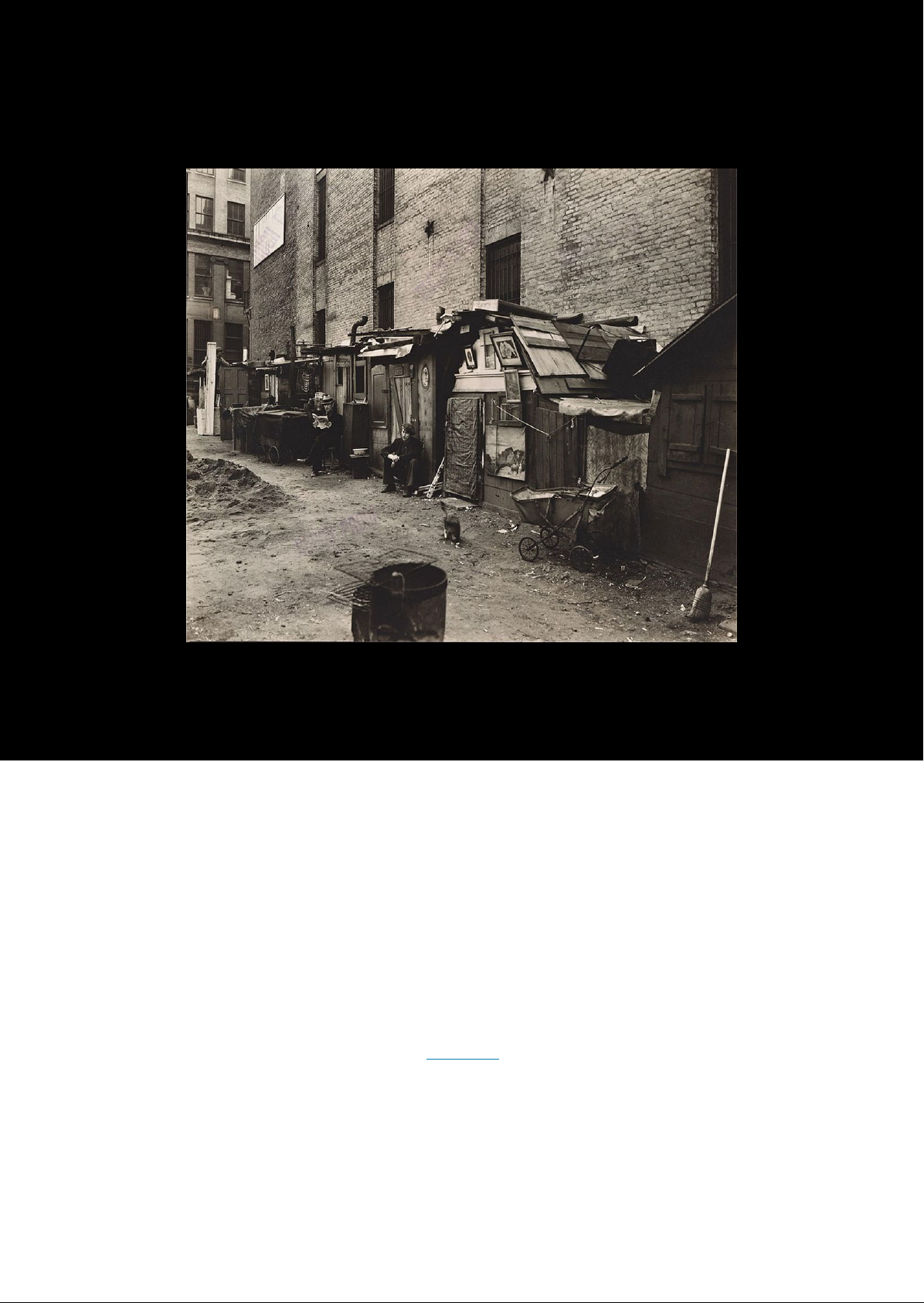

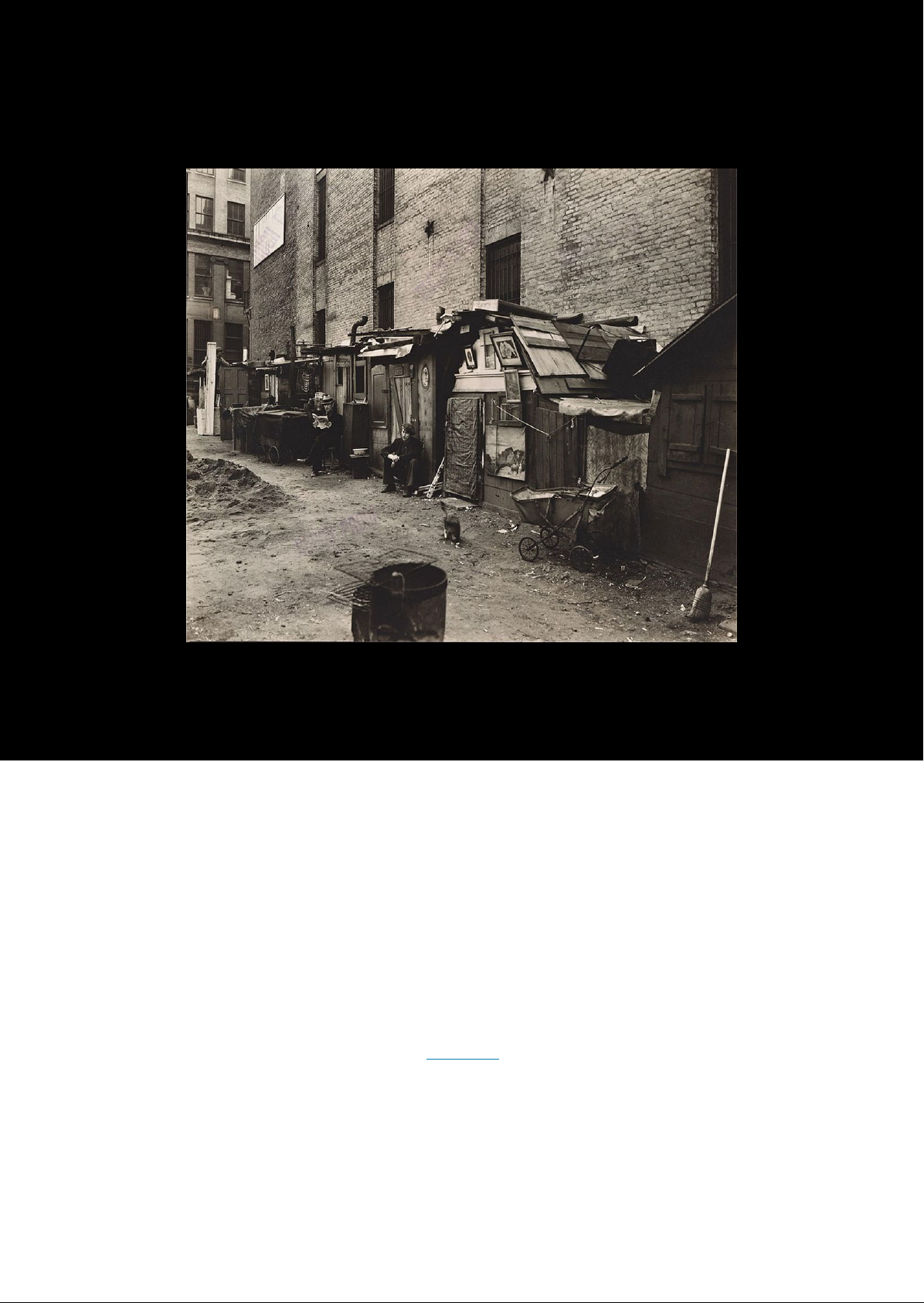

The Great Depression , FIGURE In 1935 , American photographer Abbott photographed these shanties , which the unemployed in Lower Manhattan built during the depths of the Great Depression . credit of work by Works Progress Administration ) CHAPTER OUTLINE The Stock Market Crash of 1929 President Hoover Response The Depths ofthe Great Depression Hoover Years on the Eve of the New Deal INTRODUCTION On March 1929 , at his presidential inauguration , Herbert stated , I have no fears for the future of our country . It is bright with hope . Most Americans shared his optimism . They believed that the prosperity of the would continue , and that the country was moving closer to a land of abundance ' all . Little could Hoover imagine that a year into his presidency shantytowns known as would emerge on the fringes of most major cities ) new covering the homeless would be called Hoover blankets , and pants pockets , turned to show their emptiness , would become Hoover flags . The stock market crash of October 1929 set the Great Depression into motion , but other factors were at the root of the problem , propelled onward by a series of both and natural catastrophes . Anticipating a short downturn and living under an ethos of free enterprise and individualism , Americans suffered mightily

666 25 Brother , can Vou Spare a Dime ?

The Great Depression , in the years of the Depression . As conditions worsened and the government failed to act , they grew increasingly desperate for change . While Hoover could not be blamed for the Great Depression , his failure to address the nation hardships would remain his legacy . The Stock Market Crash of 1929 LEARNING OBJECTIVES By the end ofthis section , you will be able to Identify the causes of the stock market crash of 1929 Assess the underlying weaknesses in the economy that resulted in America spiraling from prosperity to depression so quickly Compare how the stock market crash impacted different groups in America Hoover forms Reconstruction Finance Corporation Dust Bowl results from Bonus Army rial severe drought conditions breaks out in Washington and poor farming practices Roosevelt elected president 1930 1932 Hoover inaugurated president Boys trial Stock market crashes begins in Alabama Great Depression begins FIGURE ( credit courthouse of work by National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration ) Herbert Hoover became president at a time of ongoing prosperity in the country . Americans hoped he would continue to lead the country through still more economic growth , and neither he nor the country was ready for the unraveling that followed . But Hoover moderate policies , based upon a strongly held belief in the spirit of American individualism , were not enough to stem the problems , and the economy slipped further and further into the Great Depression . While it is misleading to view the stock market crash of 1929 as the sole cause of the Great Depression , the dramatic events of that October did play a role in the downward spiral of the American economy . The crash , which took place less than a year after Hoover was inaugurated , was the most extreme sign of the weakness . Multiple factors contributed to the crash , which in turn caused a consumer panic that drove the economy even further downhill , in ways that neither Hoover nor the industry was able to restrain . Hoover , like many others at the time , thought and hoped that the country would right itself with limited government intervention . This was not the case , however , and millions of Americans sank into grinding poverty . Access for free at .

The Stock Market Crash of 1929 667 THE EARLY DAYS OF PRESIDENCY Upon his inauguration , President Hoover set forth an agenda that he hoped would continue the Coolidge prosperity of the previous administration . While accepting the Republican Party presidential nomination in 1928 , Hoover commented , Given the chance to go forward with the policies of the last eight years , we shall soon with the help of God be in sight of the day when poverty will be banished from this nation forever In the spirit of normalcy that the Republican ascendancy of the , Hoover planned to immediately overhaul federal regulations with the intention of allowing the nations economy to grow unfettered by any controls . The role of the government , he contended , should be to create a partnership with the American people , in which the latter would rise ( or fall ) on their own merits and abilities . He felt the less government intervention in their lives , the better . Yet , to listen to Hoover later on Franklin Roosevelt term in , one could easily mistake his vision for America for the one held by his successor . Speaking in 1936 before an audience in Denver , Colorado , he acknowledged that it was always his intent as presiden to ensure a nation built of home owners and farm owners . We want to see more and more of them insured against death and accident , unemployment and old age , he declared . We want them all secure . Such humanitarianism was not uncommon to Hoover . Throughout his early career in public service , he was committed to relief for people around the world . In 1900 , he coordinated relief efforts for foreign nationals trapped in China curing the Boxer Rebellion . At the outset of World War I , he led the food relief effort in Europe , helping millions of Belgians who faced German forces . President Woodrow Wilson subsequently appointed him head of the Food Administration to coordinate rationing efforts in America as well as to secure essentia food items for the Allied forces and citizens in Europe . Hoover months in hinted at the reformist , humanitarian spirit that he had displayed throughout his career . He continued the civil service reform of the early century by expanding opportunities for employment throughout the federal government . In response to the Teapot Dome Affair , which had occurred during the Harding administration , he invalidated several private oi leases on public lands . He directed the Department of Justice , through its Bureau of Investigation , to crack down on organized crime , resulting in the arrest and imprisonment of Al Capone . By the summer of 1929 , he had signed into law the creation of a Federal Farm Board to help farmers with government price supports , expanded tax cuts across all income classes , and set aside federal funds to clean up slums in major American cities . To directly assist several overlooked populations , he created the Veterans Administration and expanded veterans hospitals , established the Federal Bureau of Prisons to oversee incarceration conditions nationwide , and reorganized the Bureau of Indian Affairs to further protect Native Americans . Just prior to the stock market crash , he even proposed the creation of an pension program , promising dollars monthly to all Americans over the age of proposal remarkably similar to the social security that would become a hallmark of subsequent New Deal programs . As the summer of 1929 came to a close , Hoover remained a popular successor to Calvin Silent Cal Coolidge , and all signs pointed to a highly successful administration . THE GREAT CRASH The promise of the Hoover administration was cut short when the stock market lost almost its value in the fall of 1929 , plunging many Americans into ruin . However , as a singular event , the stock market crash itself did not cause the Great Depression that followed . In fact , only approximately 10 percent of American households held stock investments and speculated in the market yet nearly a third would lose their lifelong savings and jobs in the ensuing depression . The connection between the crash and the subsequent decade of hardship was complex , involving underlying weaknesses in the economy that many policymakers had long ignored . Herbert Hoover , address delivered in Denver , Colorado , 30 October 1936 , compiled in Hoover , Addresses Upon the American Road , New York , 1938 ) 216 . This particular quotation is frequently as part of inaugural address in 1932 .

668 25 Brother , can Vou Spare a Dime ?

The Great Depression , Crash ?

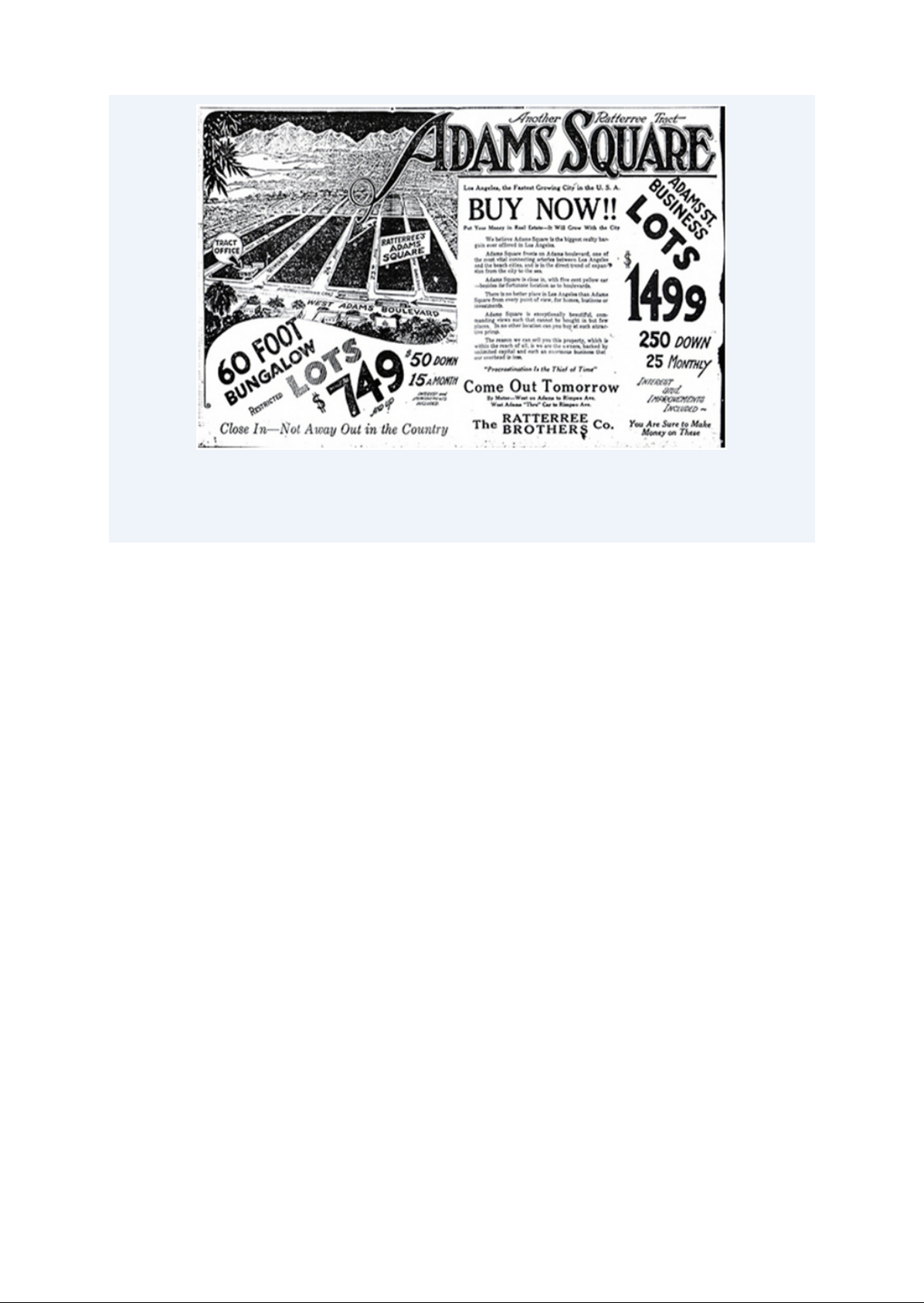

To understand the crash , it is useful to address the decade that preceded it . The prosperous 19205 ushered in a feeling of euphoria among and wealthy Americans , and people began to speculate on wilder investments . The government was a willing partner in this endeavor The Federal Reserve followed a brief postwar recession in with a policy of setting interest rates low , as well as easing the reserve requirements on the nation largest banks . As a result , the money supply in the increased by nearly 60 percent , which convinced even more Americans of the safety of investing in questionable schemes . They felt that prosperity was boundless and that extreme risks were likely tickets to wealth . Named for Charles Ponzi , the original Ponzi schemes emerged early in the to encourage novice investors to divert funds to unfounded ventures , which in reality simply used new investors funds to pay off older investors as the schemes grew in size . Speculation , where investors purchased into schemes that they hoped would pay off quickly , became the norm . Several banks , including deposit institutions that originally avoided investment loans , began to offer easy credit , allowing people to invest , even when they lacked the money to do so . An example of this mindset was the Florida land boom of the 19205 Real estate developers touted Florida as a tropical paradise and investors went all in , buying land they had never seen with money they did have and selling it for even higher prices . AMERICANA Selling Optimism and Risk Advertising offers a useful window into the popular perceptions and beliefs of an era . By seeing how businesses were presenting their goods to consumers , it is possible to sense the hopes and aspirations of people at that moment in history . Maybe companies are selling patriotism or pride in technological advances . Maybe they are pushing idealized views of parenthood or safety . In the 19205 , advertisers were selling opportunity and euphoria , further feeding the notions of many Americans that prosperity would never end . In the decade before the Great Depression , the optimism of the American public was seemingly boundless . Advertisements from that era show large new cars , timesaving labor devices , and , of course , land . This advertisement for California real estate illustrates how realtors in the West , much like the ongoing Florida land boom , used a combination ofthe hard sell and easy credit Figure . Buy now ! the ad shouts . You are sure to make money on these . In great numbers , people did . With easy access to credit and advertisements like this one , that they could not afford to miss out on such an opportunity . Unfortunately , overspeculation in California and hurricanes Gulf Coast and in Florida conspired to burst this land bubble , and millionaires were left with nothing but the ads that once pulled them in . Access for free at .

The Stock Market Crash of 1929 669 a A BUY NOW ! Ii , 1499 . 250 now yd . 15 Come Out Tomorrow If . Close In ' Array Out in Country Th ' FIGURE This real estate advertisement from Los Angeles illustrates the techniques and easy credit offered to those who wished to buy in . Unfortunately , the opportunities being promoted with these techniques were of little value , and many lost their investments . credit ) The Florida land boom went bust in . A combination of negative press about the speculative nature of the boom , IRS investigations into the questionable practices of several land brokers , and a railroad embargo hat limited the delivery of construction supplies into the region hampered investor interest . he subsequent Great Miami Hurricane of 1926 drove most land developers into outright bankruptcy . However , speculation continued throughout the decade , this time in the stock market . Buyers purchased stock on margin for a small down payment with borrowed money , with the intention of quickly selling at a much hig 181 price before the remaining payment came worked well as long as prices continued to rise . Speculators were aided by retail stock brokerage , which catered to average investors anxious to play the market but lacking direct ties to investment banking houses or larger brokerage . When prices began to in the summer of 1929 , investors sought excuses to continue their speculation . When turned to outright and steady losses , everyone started to sell . As September began to unfold , the Dow Jones Average peaked at a value of 381 points , or roughly ten times the stock markets value , at the start of the 19205 . Several warning signs portended the impending crash but went unheeded by Americans still giddy over the potential that speculation might promise . A brief downturn in the market on September 18 , 1929 , raised questions among investment bankers , leading some to predict an end to high stock values , but did little to stem the tide of investment . Even the collapse of the London Stock Exchange on September 20 failed to fully curtail the optimism of American investors . However , when the New York Stock Exchange lost 11 percent of its value on October referred to as Black Thursday American investors sat up and took notice . In an effort to forestall a panic , leading banks , including Chase National , National City , Morgan , and others , conspired to purchase large amounts ofblue chip stocks ( including Steel ) in order to keep the prices high . Even that effort failed in the growing wave of stock sales . Nevertheless , Hoover delivered a radio address on Friday in which he assured the American people , The fundamental business of the country . is on a sound and prosperous basis . As newspapers across the country began to cover the story in earnest , investors anxiously awaited the start of the following week . When the Dow Jones Industrial Average lost another 13 percent of its value on Monday morning , many knew the end of stock market speculation was near . The evening before the infamous crash was ominous . Jonathan Leonard , a newspaper reporter who regularly covered the stock market beat , wrote of

670 25 Brother , can Vou Spare a Dime ?

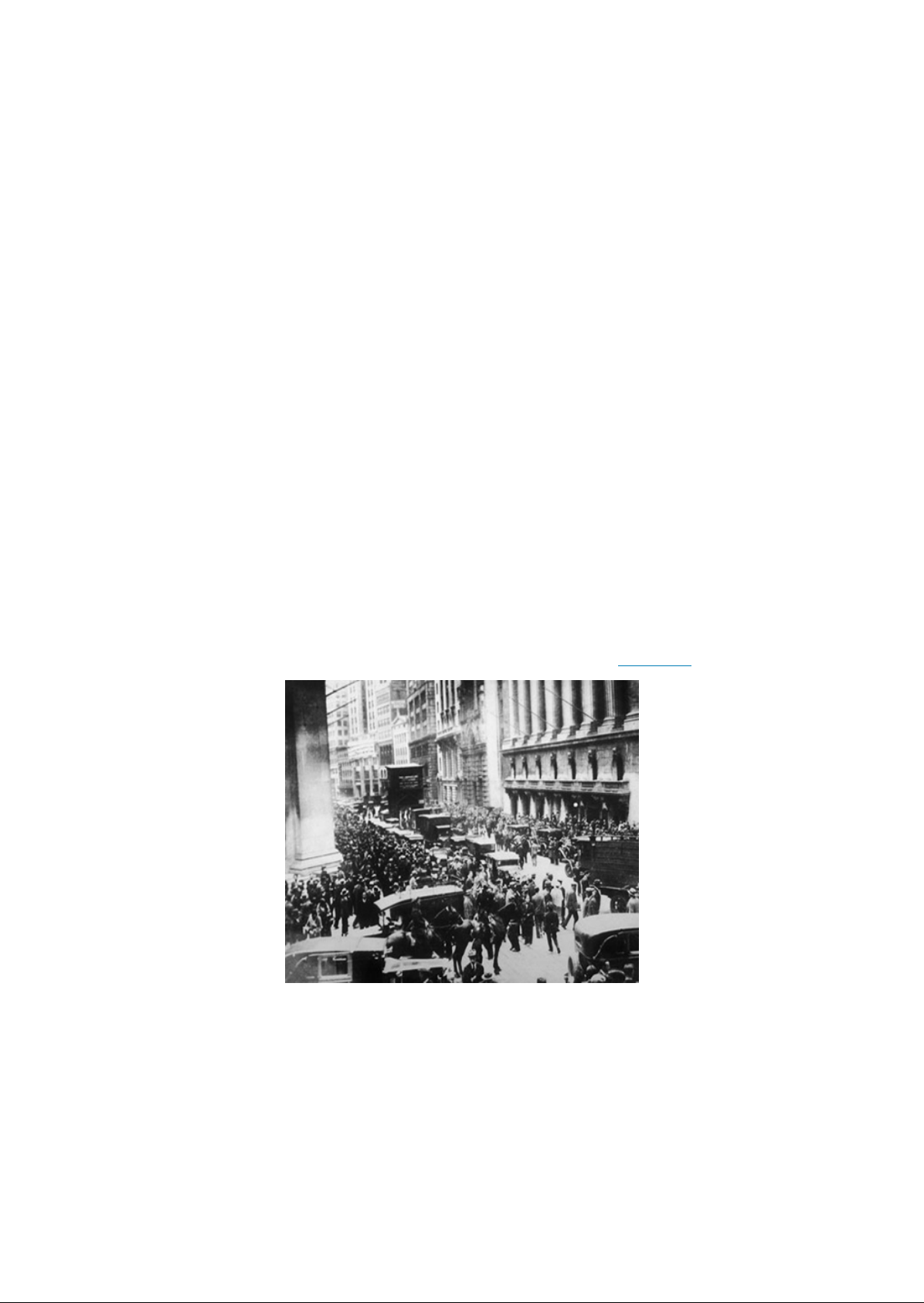

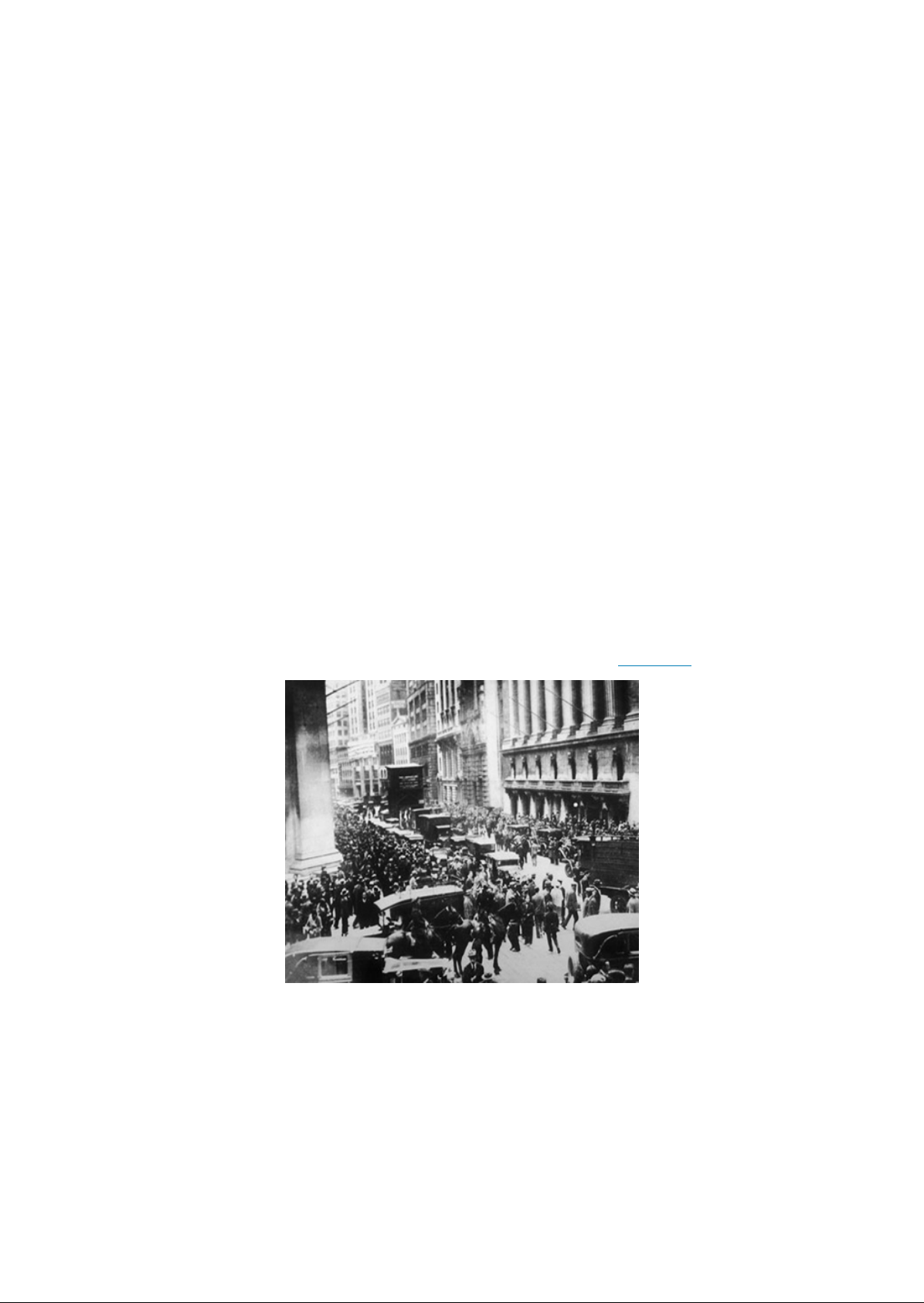

The Great Depression , how Wall Street lit up like a Christmas tree . Brokers and businessmen who feared the worst the next day crowded into restaurants and speakeasies ( a place where alcoholic beverages were illegally sold ) After a night of heavy drinking , they retreated to nearby hotels or ( cheap boarding houses ) all of which were overbooked , and awaited sunrise . Children from nearby slums and tenement districts played stickball in the streets of the district , using wads of ticker tape for balls . Although they all awoke to newspapers with predictions of a turnaround , as well as technical reasons why the decline might be , the crash on Tuesday morning , October 29 , caught few by surprise . No one even heard the opening bell on Wal Street that day , as shouts of Sell ! Sell ! drowned it out . In the three minutes alone , nearly three million of stock , accounting for million of wealth , changed hands . The volume of Western Union telegrams tripled , and telephone lines could not meet the demand , as investors sought any means available to dump their stock immediately . Rumors spread of investors jumping from their windows . broke out on the , where one broker fainted from physical exhaustion . Stock trades happened at such a furious pace that runners had nowhere to store the trade slips , and so they resorted to them into trash cans . A though the stock exchanges board of governors considered closing the exchange early , they subsequently chose to let the market run its course , lest the American public panic even further at the thought of closure . When the bell rang , errand boys spent hours sweeping up tons of paper , and sales slips . Among the more curious in the rubbish were torn suit coats , crumpled eyeglasses , and one broker leg . Outside a nearby brokerage house , a policeman allegedly found a discarded birdcage with a live parrot squawking , More margin ! More margin ! On Black Tuesday , October 29 , stock holders traded over sixteen million shares and lost over 14 billion in wealth in a single day . To put this in , a trading day of three million shares was considered a busy day on the stock market . People unloaded their stock as quickly as they could , never minding the loss . Banks , facing debt and seeking to protect their own assets , demanded payment for the loans they had provided to individual investors . Those individuals who could not afford to pay found their stocks sold immediately and their life savings wiped out in minutes , yet their debt to the bank still remained ( Figure ) FIGURE October 29 , 1929 , or Black Tuesday , witnessed thousands of people racing to Wall Street discount brokerages and markets to sell their stocks . Prices plummeted throughout the day , eventually leading to a complete stock market crash . The outcome of the crash was devastating . Between September and November 30 , 1929 , the stock market lost over its value , dropping from 64 billion to approximately 30 billion . Any effort to stem the tide was , as one historian noted , tantamount to bailing Niagara Falls with a bucket . The crash affected many more than the relatively few Americans who invested in the stock market . While only 10 percent of households had investments , over 90 percent of all banks had invested in the stock market . Many banks failed due to their dwindling cash reserves . This was in part due to the Federal Reserve lowering the limits of cash Access for free at .

The Stock Market Crash of 1929 671 reserves that banks were traditionally required to hold in their vaults , as well as the fact that many banks invested in the stock market themselves . Eventually , thousands of banks closed their doors after losing all of their assets , leaving their customers penniless . While a few savvy investors got out at the right time and eventually made fortunes buying up discarded stock , those success stories were rare . Housewives who speculated with grocery money , bookkeepers who embezzled company funds hoping to strike it rich and pay the funds back before getting caught , and bankers who used customer deposits to follow speculative trends all lost . While the stock market crash was the trigger , the lack of appropriate economic and banking safeguards , along with a public psyche that pursued wealth and prosperity at all costs , allowed this event to spiral downward into a depression . CLICK AND EXPLORE The National Humanities Center ( I crash ) has brought together a selection of newspaper commentary from the , from before the crash to its aftermath . Read through to see what journalists and analysts thought of the situation at the time . Causes ofthe Crash The crash of 1929 did not occur in a vacuum , nor did it cause the Great Depression . Rather , it was a tipping point where the underlying weaknesses in the economy , in the nation banking system , came to the fore . It also represented both the end of an era characterized by blind faith in American and the beginning of one in which citizens began increasingly to question some American values . A number of factors played a role in bringing the stock market to this point and contributed to the downward trend in the market , which continued well into the . In addition to the Federal Reserve questionable policies and misguided banking practices , three primary reasons for the collapse of the stock market were international economic woes , poor income distribution , and the psychology of public . After World War I , both America allies and the defeated nations of Germany and Austria contended with disastrous economies . The Allies owed large amounts of money to banks , which had advanced them money during the war effort . Unable to repay these debts , the Allies looked to reparations from Germany and Austria to help . The economies of those countries , however , were struggling badly , and they could not pay their reparations , despite the loans that the provided to assist with their payments . The government refused to forgive these loans , and American banks were in the position of extending additional private loans to foreign governments , who used them to repay their debts to the government , essentially shifting their obligations to private banks . When other countries began to default on this second wave of private bank loans , still more strain was placed on banks , which soon sought to liquidate these loans at the sign of a stock market crisis . Poor income distribution among Americans compounded the problem . A strong stock market relies on today buyers becoming tomorrow sellers , and therefore it must always have an of new buyers . In the , this was not the case . Eighty percent of American families had virtually no savings , and only to percent of Americans controlled over a third of the wealth . This scenario meant that there were no new buyers coming into the marketplace , and nowhere for sellers to unload their stock as the speculation came to a close . In addition , the vast majority of Americans with limited savings lost their accounts as local banks closed , and likewise lost theirjobs as investment in business and industry came to a screeching halt . Finally , one of the most important factors in the crash was the contagion effect . For much of the , the public felt that prosperity would continue forever , and therefore , in a cycle , the market continued to grow . But once the panic began , it spread quickly and with the same cyclical results people were worried that the market was going down , they sold their stock , and the market continued to drop . This was partly due to Americans inability to weather market volatility , given the limited cash surpluses they had on hand , as well as their psychological concern that economic recovery might never happen .

672 25 Brother , can Vou Spare a Dime ?

The Great Depression , IN THE AFTERMATH OF THE CRASH After the crash , Hoover announced that the economy was fundamentally sound . On the last day of trading in 1929 , the New York Stock Exchange held its annual wild and lavish party , complete with confetti , musicians , and illegal alcohol . The Department of Labor predicted that 1930 would be a splendid employment year . These sentiments were not as baseless as it may seem in hindsight . Historically , markets cycled up and down , and periods of growth were often followed by that corrected themselves . But this time , there was no market correction rather , the abrupt shock of the crash was followed by an even more devastating depression . Investors , along with the general public , withdrew their money from banks by the thousands , fearing the banks would go under . The more people pulled out their money in bank runs , the closer the banks came to insolvency Figure . FIGURE As the markets collapsed , hurting the banks that had gambled with their holdings , people began to fear that the money they had in the bank would be lost . This began bank runs across the country , a period of still more panic , where people pulled their money out of banks to keep it hidden at home . The contagion effect of the crash grew quickly . With investors losing billions of dollars , they invested very little in new or expanded businesses . At this time , two industries had the greatest impact on the country economic future in terms of investment , potential growth , and employment automotive and construction . After the crash , both were hit hard . In November 1929 , fewer cars were built than in any other month since November 1919 . Even before the crash , widespread saturation of the market meant that few Americans bought them , leading to a slowdown . Afterward , very few could afford luxury cars , like , and , so these car companies gradually went out of business in the . In construction , the was even more dramatic . It would be another thirty years before a new hotel or theater was built in New York City . The Empire State Building itself stood half empty for years after being completed in 1931 . The damage to major industries led to , and , limited purchasing by both consumers and businesses . Even those Americans who continued to make a modest income during the Great Depression lost the drive for conspicuous consumption that they exhibited in the . People with less money to buy goods could not help businesses grow in turn , businesses with no market for their products could not hire workers or purchase raw materials . Employers began to lay off workers . The country gross national product declined by over 25 percent within a year , and wages and salaries declined by billion . Unemployment tripled , from million at the end of 1929 to million by the end of 1930 . By , the slide into economic chaos had begun but was nowhere near complete . THE NEW REALITY FOR AMERICANS For most Americans , the crash affected daily life in myriad ways . In the immediate aftermath , there was a run Access for free at .

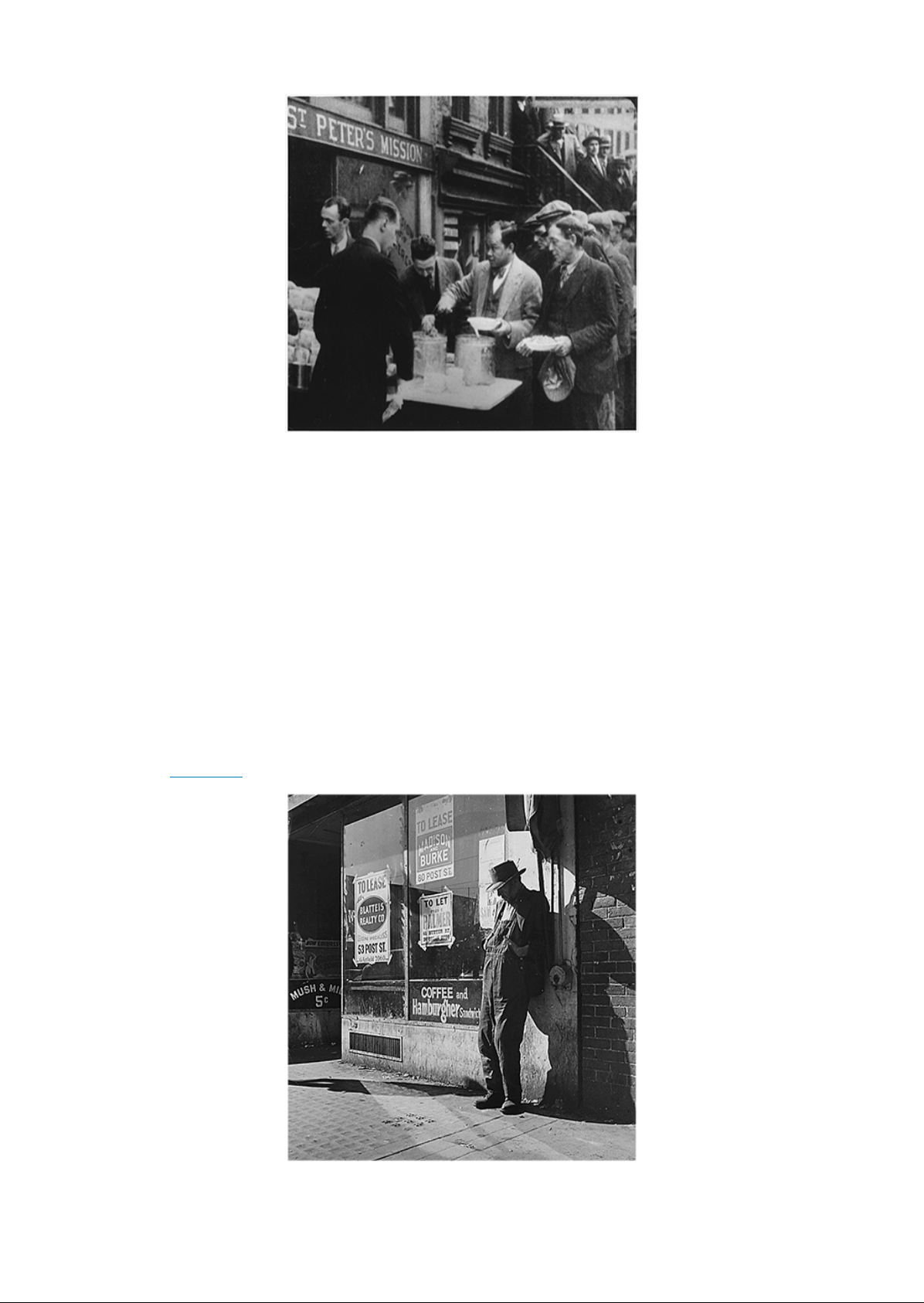

The Stock Market Crash of 1929 673 on the banks , where citizens took their money out , if they could get it , and hid their savings under mattresses , in bookshelves , or anywhere else they felt was safe . Some went so far as to exchange their dollars for gold and ship it out of the country . A number of banks failed outright , and others , in their attempts to stay solvent , called in loans that people could not afford to repay . Americans saw their wages drop Even Henry Ford , the champion of a high minimum wage , began lowering wages by as much as a dollar a day . Southern cotton planters paid workers only twenty cents for every one hundred pounds of cotton picked , meaning that the might earn sixty cents for a day of work . Cities struggled to collect property taxes and subsequently laid off teachers and police . The new hardships that people faced were not always immediately apparent many communities felt the changes but could not necessarily look out their windows and see anything different . Men who lost their jobs did stand on street corners begging they disappeared . They might be found keeping warm by a trashcan or picking through garbage at dawn , but mostly , they stayed out of public view . As the effects of the crash continued , however , the results became more evident . Those living in cities grew accustomed to seeing long of unemployed men waiting for a meal ( Figure . Companies workers and tore down employee housing to avoid paying property taxes . The landscape of the country had changed . FIGURE As the Great Depression set in , thousands of unemployed men lined up in cities around the country , waiting for a free meal or a hot cup of coffee . The hardships of the Great Depression threw family life into disarray . Both marriage and birth rates declined in the decade after the crash . The most vulnerable members of , women , minorities , and the working the most . Parents often sent children out to beg for food at restaurants and stores to save themselves from the disgrace of begging . Many children dropped out of school , and even fewer went to college . Childhood , as it had existed in the prosperous twenties , was over . And yet , for many children living in rural areas where the of the previous decade was not fully developed , the Depression was not viewed as a great challenge . School continued . Play was simple and enjoyed . Families adapted by growing more in gardens , canning , and preserving , wasting little food if any . clothing became the norm as the decade progressed , as did creative methods of shoe repair with cardboard soles . Yet , one always knew of stories of the other families who suffered more , including those living in cardboard boxes or caves . By one estimate , as many as children moved about the country as vagrants due to familial disintegration . Women lives , too , were profoundly affected . Some wives and mothers sought employment to make ends meet , an undertaking that was often met with strong resistance from husbands and potential employers . Many men derided and criticized women who worked , feeling that jobs should go to unemployed men . Some campaigned to keep companies from hiring married women , and an increasing number of school districts expanded the practice of banning the hiring of married female teachers . Despite the pushback ,

674 25 Brother , Can Vou Spare a Dime ?

The Great Depression , women entered the workforce in increasing numbers , from ten million at the start of the Depression to nearly thirteen million by the end of the . This increase took place in spite of the states that passed a variety of laws to prohibit the employment of married women . Several women found employment in the emerging pink collar occupations , viewed as traditional women work , including jobs as telephone operators , social workers , and secretaries . Others took jobs as maids and , working for those fortunate few who had maintained their wealth . White women forays into domestic service came at the expense of minority women , who had even fewer employment options . Unsurprisingly , African American men and women experienced unemployment , and the grinding poverty that followed , at double and triple the rates of their White counterparts . By 1932 , unemployment among African Americans reached near 50 percent . In rural areas , where large numbers of African Americans continued to live despite the Great Migration of , life represented an version of the poverty that they traditionally experienced . Subsistence farming allowed many African Americans who lost either their land or jobs working for White landholders to survive , but their hardships increased . Life for African Americans in urban settings was equally trying , with Black people and White people living in close proximity and competing for scarce jobs and resources . Life for all rural Americans was . Farmers largely did not experience the widespread prosperity of the . Although continued advancements in farming techniques and agricultural machinery led to increased agricultural production , decreasing demand ( particularly in the previous markets created by World War I ) steadily drove down commodity prices . As a result , farmers could barely pay the debt they owed on machinery and land mortgages , and even then could do so only as a result of generous lines of credit from banks . While factory workers may have lost their jobs and savings in the crash , many farmers also lost their homes , due to the thousands of farm foreclosures sought by desperate bankers . Between 1930 and 1935 , nearly family farms disappeared through foreclosure or bankruptcy . Even for those who managed to keep their farms , there was little market for their crops . Unemployed workers had less money to spend on food , and when they did purchase goods , the market excess had driven prices so low that farmers could barely piece together a living . A example of the farmer plight is that , when the price of coal began to exceed that of corn , farmers would simply burn corn to stay warm in the winter . As the effects of the Great Depression worsened , wealthier Americans had particular concern for the deserving poor who had lost all of their money due to no fault of their own . This concept gained greater attention beginning in the Progressive Era of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries , when early social reformers sought to improve the quality of life for all Americans by addressing the poverty that was becoming more prevalent , particularly in emerging urban areas . By the time of the Great Depression , social reformers and humanitarian agencies had determined that the deserving poor belonged to a different category from those who had speculated and lost . However , the sheer volume of Americans who fell into this group meant that charitable assistance could not begin to reach them all . Some million deserving poor , or a full of the labor force , were struggling by 1932 . The country had no mechanism or system in place to help so many however , Hoover remained adamant that such relief should rest in the hands of private agencies , not with the federal government Figure . Access for free at .

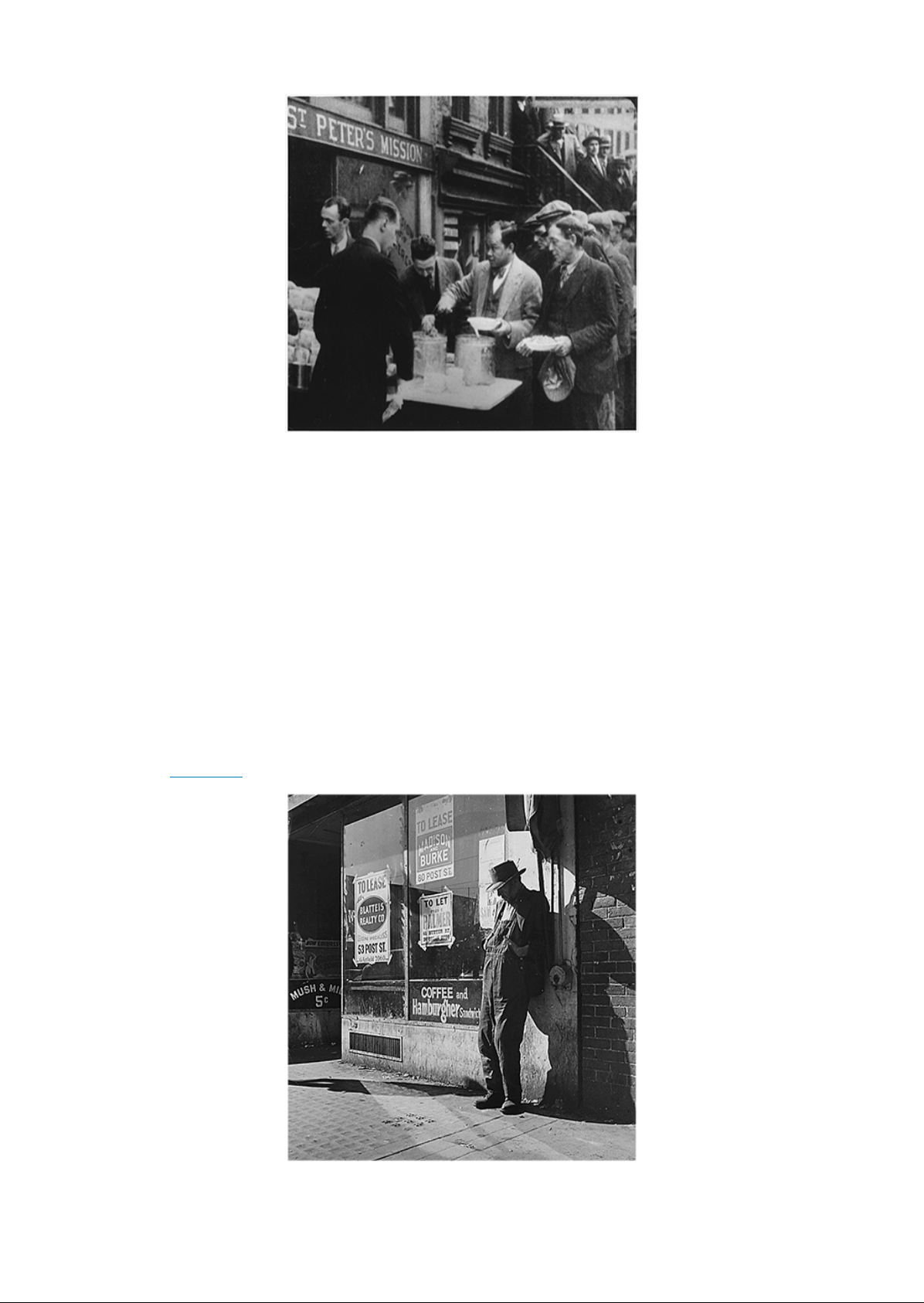

The Stock Market Crash of 1929 675 FIGURE In the early , without government relief programs , many people in urban centers relied on private agencies for assistance . In New York City , Peter Mission distributed bread , soup , and canned goods to large numbers of the unemployed and others in need . Unable to receive aid from the government , Americans thus turned to private charities churches , synagogues , and other religious organizations and state aid . But these organizations were not prepared to deal with the scope of the problem . Private aid organizations showed declining assets as well during the Depression , with fewer Americans possessing the ability to donate to such charities . Likewise , state governments were particularly . Governor Franklin Roosevelt was the to institute a Department of Welfare in New York in 1929 . City governments had equally little to offer . In New York City in 1932 , family allowances were per week , and only of the families who actually received them . In Detroit , allowances fell to cents a day per person , and eventually ran out completely . In most cases , relief was only in the form of food and fuel organizations provided nothing in the way of rent , shelter , medical care , clothing , or other necessities . There was no infrastructure to support the elderly , who were the most vulnerable , and this population largely depended on their adult children to support them , adding to families burdens ( Figure . FIGURE Because there was no infrastructure to support them should they become unemployed or destitute ,

676 25 Brother , Can Vou Spare a Dime ?

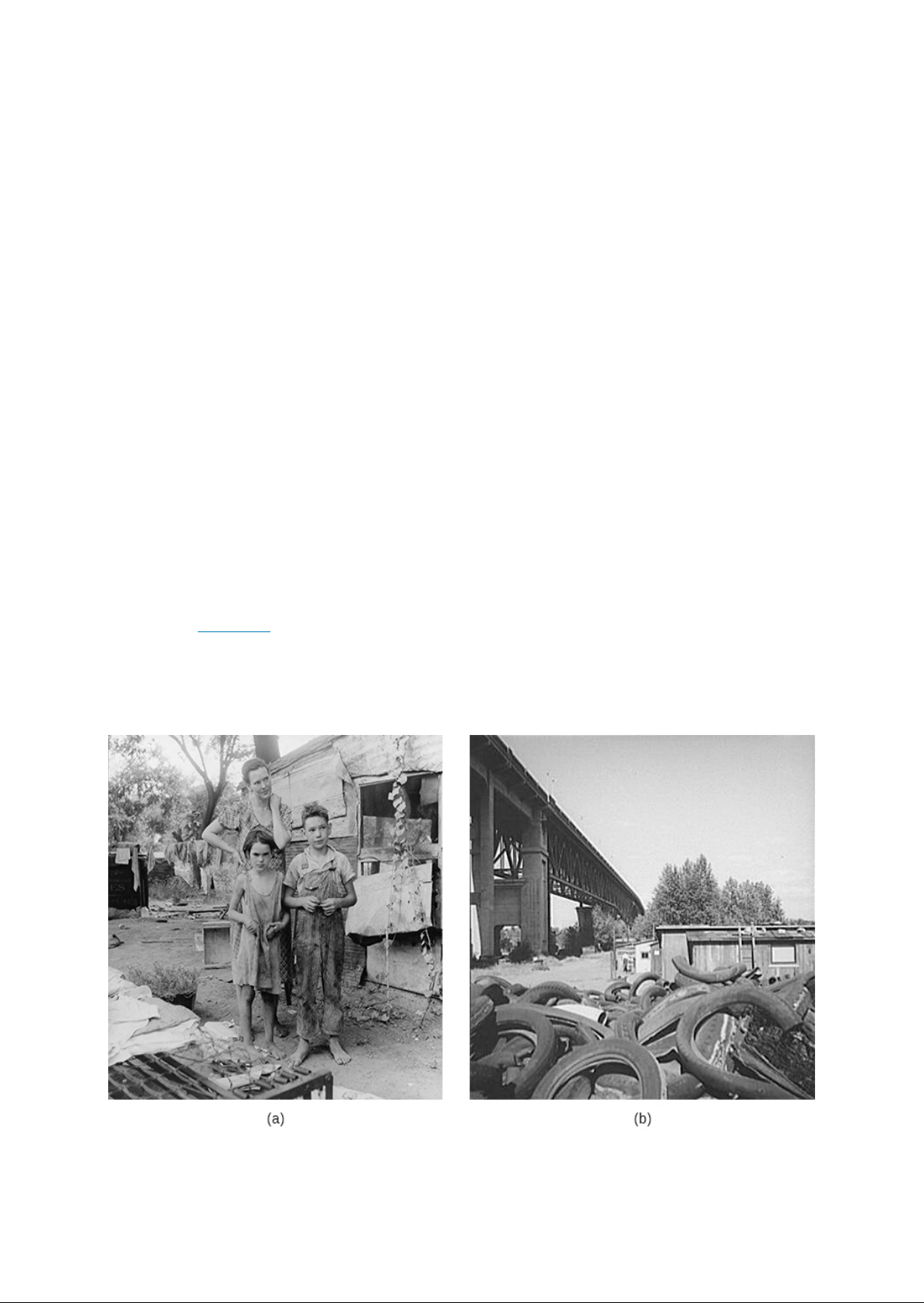

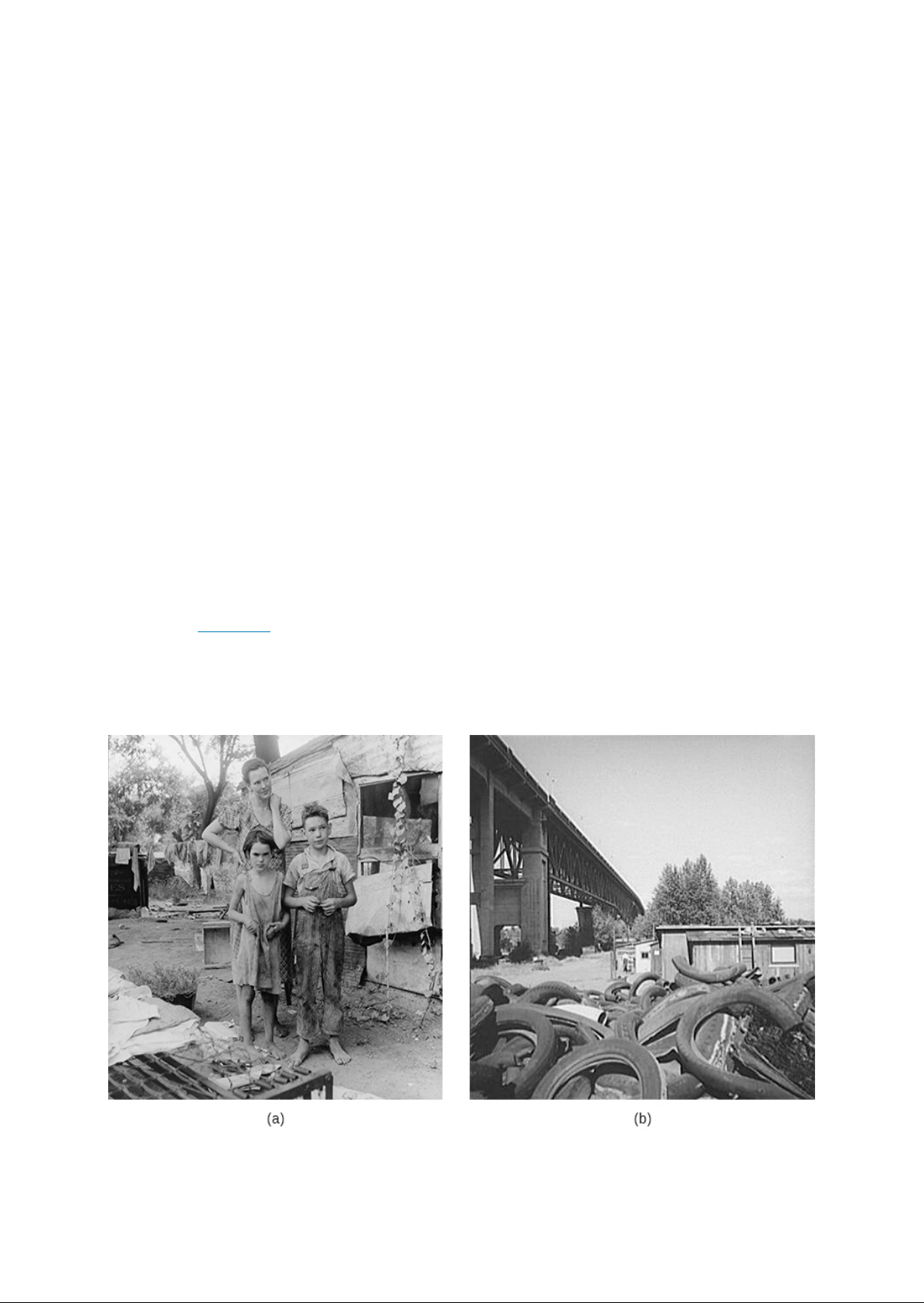

The Great Depression , the elderly were extremely vulnerable during the Great Depression . As the depression continued , the results of this tenuous situation became more evident , as shown in this photo of a vacant storefront in San Francisco , captured by Lange in 1935 . During this time , local community groups , such as police and teachers , worked to help the neediest . New York City police , for example , began contributing percent of their salaries to start a food fund that was geared to help those found starving on the streets . In 1932 , New York City schoolteachers also joined forces to try to help they contributed as much as per month from their own salaries to help needy children . Chicago teachers did the same , feeding some eleven thousand students out of their own pockets in 1931 , despite the fact that many of them had not been paid a salary in months . These noble efforts , however , failed to fully address the level of desperation that the American public was facing . President Hoover Response LEARNING OBJECTIVES By the end ofthis section , you will be able to Explain Herbert Hoover responses to the Great Depression and how hey reflected his political philosophy Describe the causes , objectives , and outcomes of Great Depression protests Analyze the frustration and anger that a majority of Americans at Herbert Hoover President Hoover was unprepared for the scope of the depression crisis , and his limited response did not begin to help the millions in need . The steps he took were very much in keeping with his philosophy of limited government , a philosophy that many had shared with him until he upheavals of the Great Depression made it clear that a more direct government response was required . Bu Hoover was stubborn in his refusal to give handouts , as he saw direct government aid . He called for a spirit of volunteerism among businesses , asking them to keep workers employed , and he exhorted the American people to tighten their belts and make do in the spirit of rugged individualism . While Hoover phi osophy and his appeal to the country were very much in keeping with his character , it was not enough to keep the economy from plummeting further into economic chaos . The steps Hoover did ultimately take were too little , too late . He created for putting people back to work and helping beleaguered local and state charities with aid . But the programs were small in scale and highly as to who could , and they only touched a small percentage of those in need . As the situation worsened , the public grew increasingly unhappy with Hoover . Ie left with one of the lowest approval ratings of any president in history . THE INITIAL REACTION In the immediate aftermath of Black Tuesday , Hoover sought to reassure Americans that all was well . Reading his words after the fact , it is easy to fault . In 1929 he said , Any lack of in the economic future or the strength of business in the United States is foolish . In 1930 , he stated , The worst is behind us . In 1931 , he pledged federal aid should he ever witness starvation in the country but as of that date , he had yet to see such need in America , despite the very real evidence that children and the elderly were starving to death . Yet Hoover was neither intentionally blind nor unsympathetic . He simply held fast to a belief system that did not change as the realities of the Great Depression set in . Hoover believed strongly in the ethos of American individualism that hard work brought its own rewards . His life story to that belief . Hoover was born into poverty , made his way through college at Stanford University , and eventually made his fortune as an engineer . This experience , as well as his extensive travels in China and throughout Europe , shaped his fundamental conviction that the very existence of American civilization depended upon the moral of its citizens , as evidenced by their ability to overcome all hardships through individual effort and resolve . The idea of government handouts to Americans was repellant to him . Whereas Europeans might need assistance , such as his hunger relief work in Belgium during and after World War I , he believed the American character to be different . In a 1931 radio address , he said , The spread Access for free at .

President Hoover Response 677 of government destroys initiative and thus destroys Likewise , Hoover was not completely unaware of the potential harm that wild stock speculation might create if left unchecked . As secretary of commerce , Hoover often warned President Coolidge of the dangers that such speculation engendered . In he weeks before his inauguration , he offered many interviews to newspapers and magazines , urging Americans to curtail their rampant stock investments , and even encouraged the Federal Reserve to raise the rate to make it more costly for local banks to lend money to potential speculators . However , fearful of creating a panic , Hoover never issued a stern warning to discourage Americans from such investments . Neither Hoover , nor any other politician of that day , ever gave serious thought to outright government regulation of the stock market . This was even true in his personal choices , as Hoover often lamented poor stock advice ie had once offered to a friend . When the stock , Hoover bought the shares from his friend to assuage his guilt , vowing never again to advise anyone on matters of investment . In keeping with these ales , Hoover response to the crash focused on two very common American traditions He asked individuals to tighten their belts and work harder , and he asked the business community to voluntarily help sustain the economy by retaining workers and continuing production . He immediately summoned a conference of eading industrialists to meet in Washington , urging them to maintain their current wages while America rode out this brief economic panic . The crash , he assured business leaders , was not part of a greater downturn they had nothing to worry about . Similar meetings with utility companies and railroad executives elicited for billions of dollars in new construction projects , while labor leaders agreed to withhold demands for wage increases and workers continued to labor . Hoover also persuaded Congress to pass a 160 million tax cut to bolster American incomes , leading many to conclude that the president was doing all he could to stem the tide of the panic . In April 1930 , the New York Times editorial board concluded that No one in his place could have done However , these modest steps were not enough . By late 1931 , when it became clear that the economy would not improve on its own , Hoover recognized the need for some government intervention . He created the Presidents Emergency Committee for Employment ( later renamed the Presidents Organization of Unemployment Relief ( POUR ) In keeping with Hoover distaste of what he viewed as handouts , this organization did not provide direct federal relief to people in need . Instead , it assisted state and private relief agencies , such as the Red Cross , Salvation Army , YMCA , and Community Chest . Hoover also strongly urged people of means to donate funds help the poor , and he himself gave private donations to worthy causes . But these private efforts could not alleviate the widespread effects of poverty . Congress pushed for a more direct government response to the hardship . In , it attempted to pass a 60 million bi to provide relief to drought victims by allowing them access to food , fertilizer , and animal feed . Hoover stood ast in his refusal to provide food , resisting any element of direct relief . The bill of 47 million provided for everything but did not come close to adequately addressing the crisis . Again in 1931 , Congress proposed the Federal Emergency Relief Bill , which would have provided 375 million to states to help food , clothing , and shelter to the homeless . But Hoover opposed the bill , stating that it ruined the ba ance of power between states and the federal government , and in February 1932 , it was defeated by fourteen votes . However , the residents adamant opposition to federal government programs should not be viewed as one of indifference or uncaring toward the suffering American people . His personal sympathy for those in need was boundless . Hoover was one of only two presidents to reject his salary for the he held . Throughout tie Great Depression , he donated an average of annually to various relief organizations to assist in their efforts . Furthermore , he helped to raise in private funds to support the White House Conference on Child Health and Welfare in 1930 . Rather than indifference or heartlessness , Hoover steadfast adherence to a philosophy of individualism as the path toward American recovery explained many of his policy decisions . A voluntary deed , he repeatedly commented , is more precious to our national ideal and spirit than a poured from the Treasury .

678 25 Brother , can Vou Spare a Dime ?

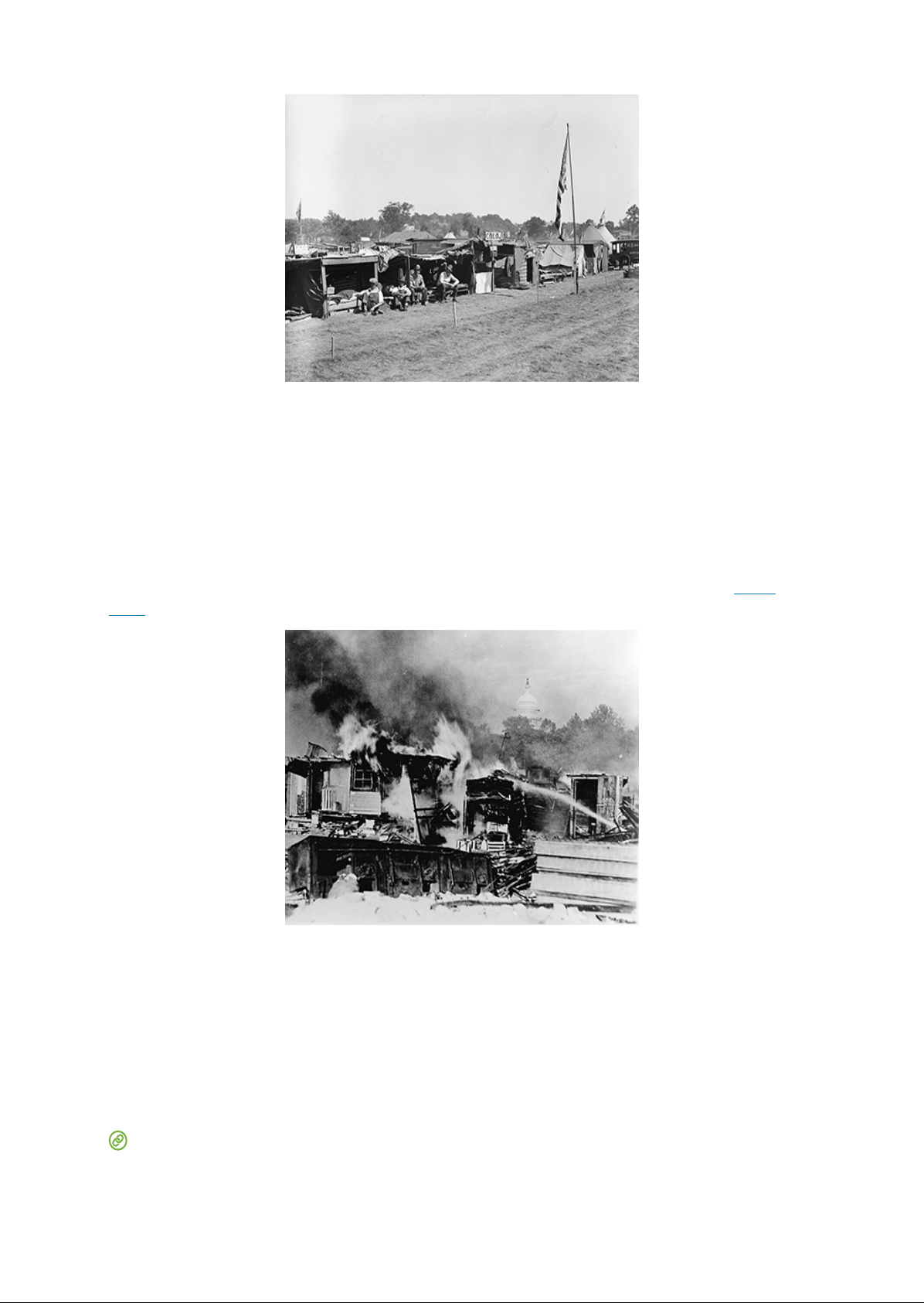

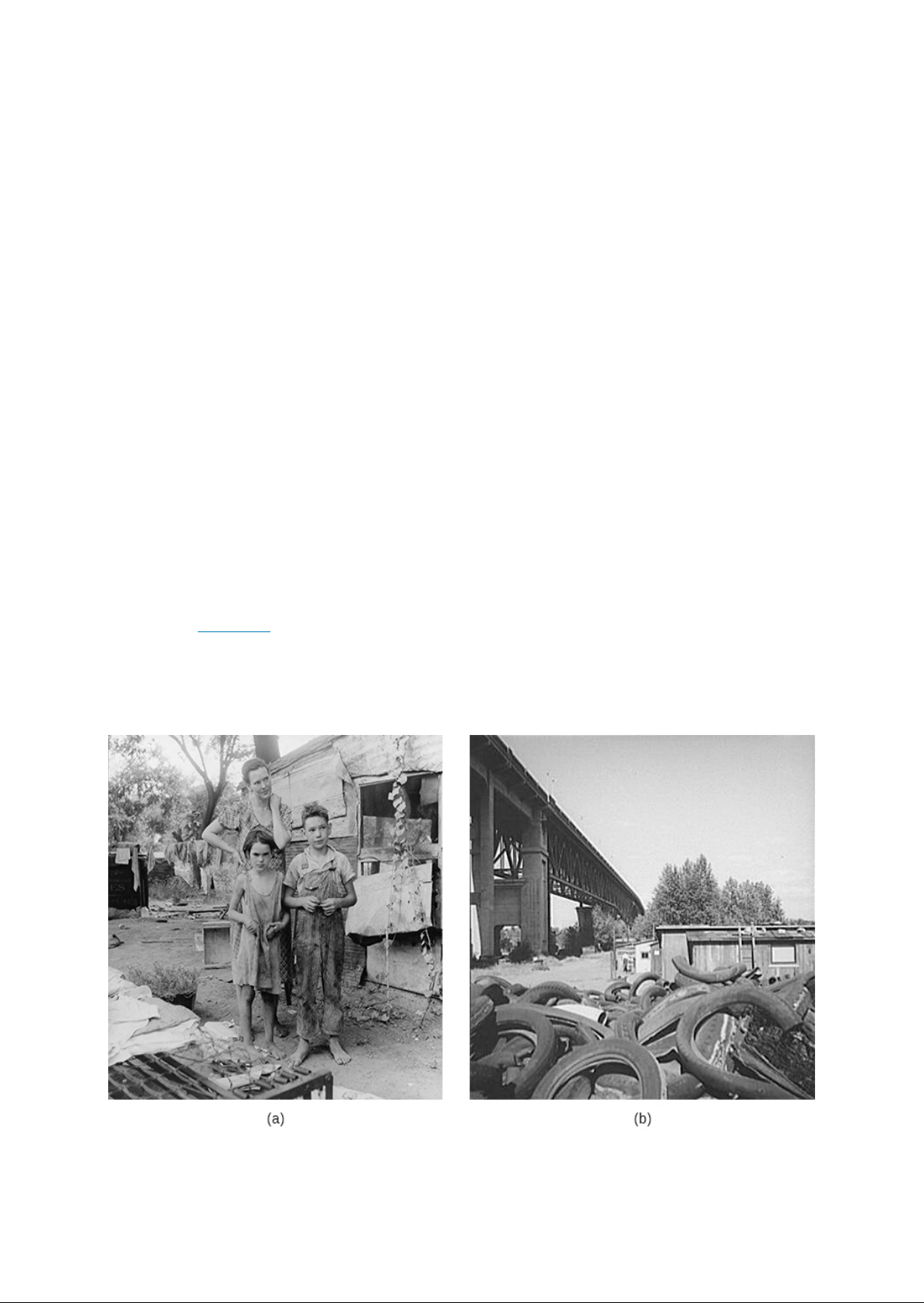

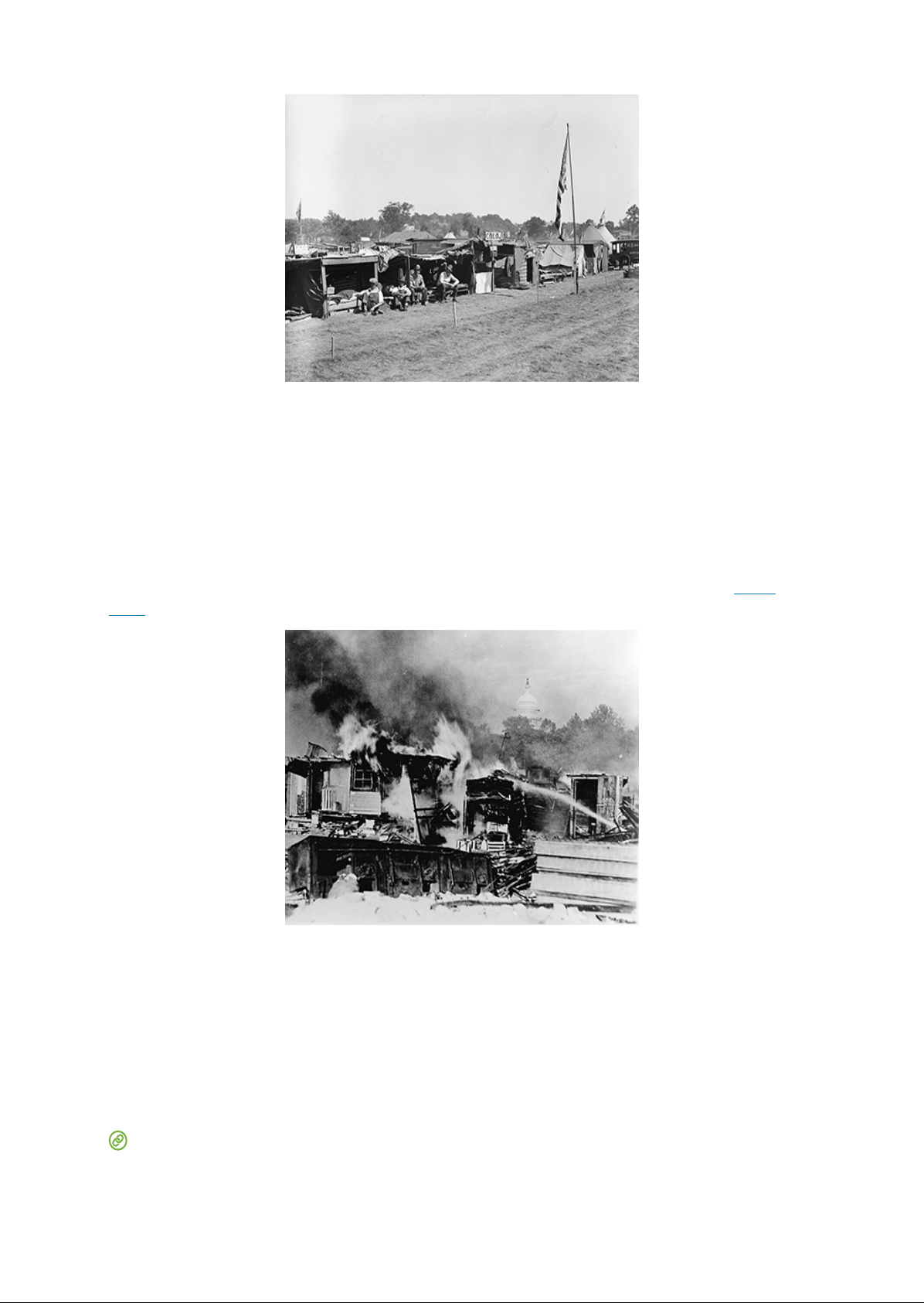

The Great Depression , As conditions worsened , however , Hoover eventually relaxed his opposition to federal relief and formed the Reconstruction Finance Corporation ( in 1932 , in part because it was an election year and Hoover hoped to keep his . Although not a form of direct relief to the American people in greatest need , the was much larger in scope than any preceding effort , setting aside billion in taxpayer money to rescue banks , credit unions , and insurance companies . The goal was to boost in the nation institutions by ensuring that they were on solid footing . This model was on a number of levels . First , the program only lent money to banks with collateral , which meant that most of the aid went to large banks . In fact , of the 61 million loaned , 41 million went to just three banks . Small town and rural banks got almost nothing . Furthermore , at this time , in institutions was not the primary concern of most Americans . They needed food and jobs . Many had no money to put into the banks , no matter how they were that the banks were safe . Hoover other attempt at federal assistance also occurred in 1932 , when he endorsed a bill by Senator Robert Wagner of New York . This was the Emergency Relief and Construction Act . This act authorized the to expand beyond loans to institutions and allotted billion to states to fund local public works projects . This program failed to deliver the kind of help needed , however , as Hoover severely limited the types of projects it could fund to those that were ultimately ( such as toll bridges and public housing ) and those that required skilled workers . While well intended , these programs maintained the status quo , and there was still no direct federal relief to the individuals who so desperately needed it . PUBLIC REACTION TO HOOVER Hoover steadfast resistance to government aid cost him the reelection and has placed him squarely at the forefront of the most unpopular presidents , according to public opinion , in modern American history . His name became synonymous with the poverty of the era became the common name for homeless shantytowns Figure and Hoover blankets for the newspapers that the homeless used to keep warm . A Hoover was a pants of all inside out . By the 1932 election , hitchhikers held up signs reading If you do give me a ride , I vote for Hoover . Americans did not necessarily believe that Hoover caused the Great Depression . Their anger stemmed instead from what appeared to be a willful refusal to help regular citizens with direct aid that might allow them to recover from the crisis . FIGURE Hoover became one of the least popular presidents in history . or shantytowns , were a negative reminder of his role in the nation crisis . This family ( a ) lived in a in Elm Grove , Oklahoma . This shanty ( was one of many making up a in the Portland , Oregon area . credit Access for free at .

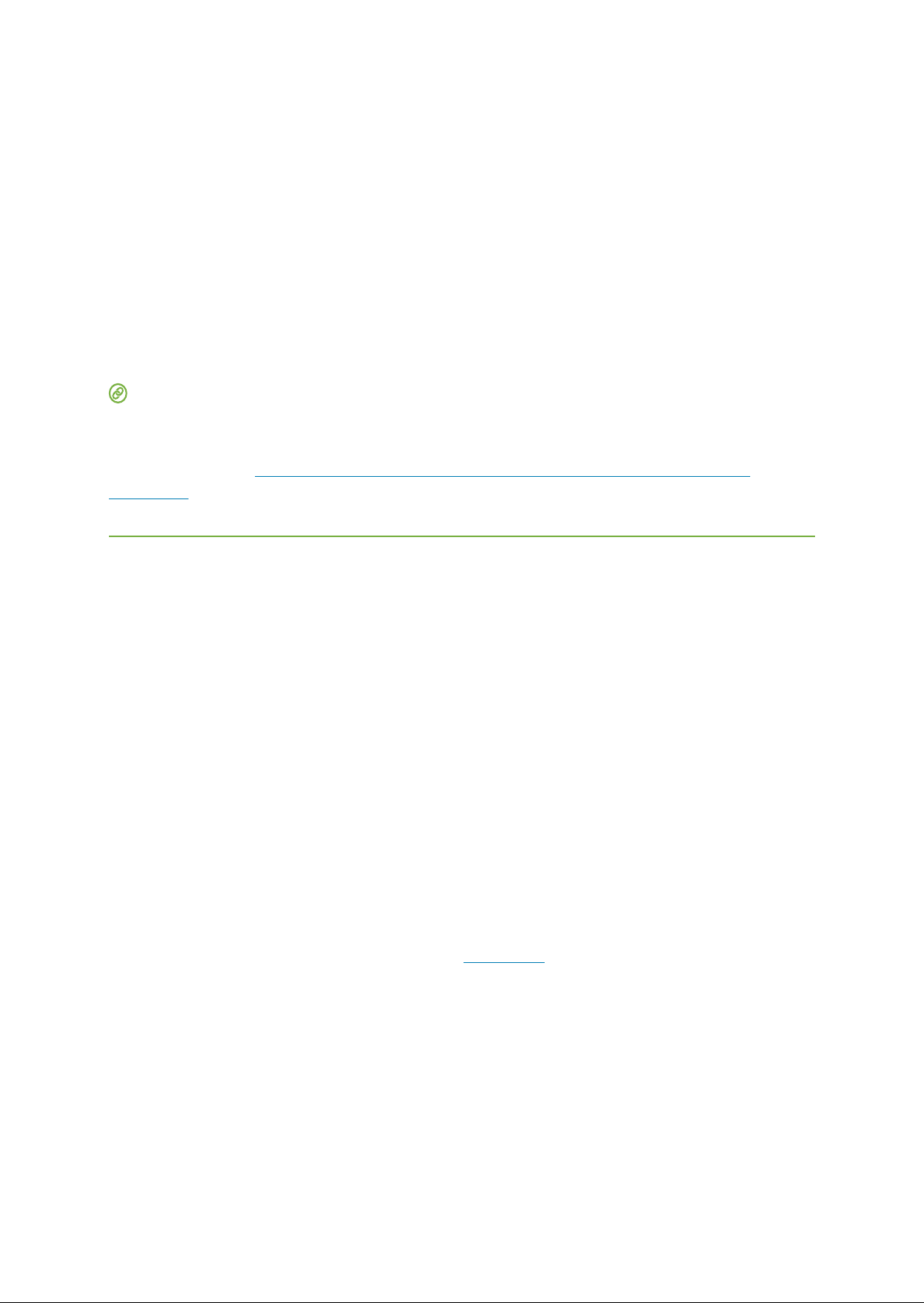

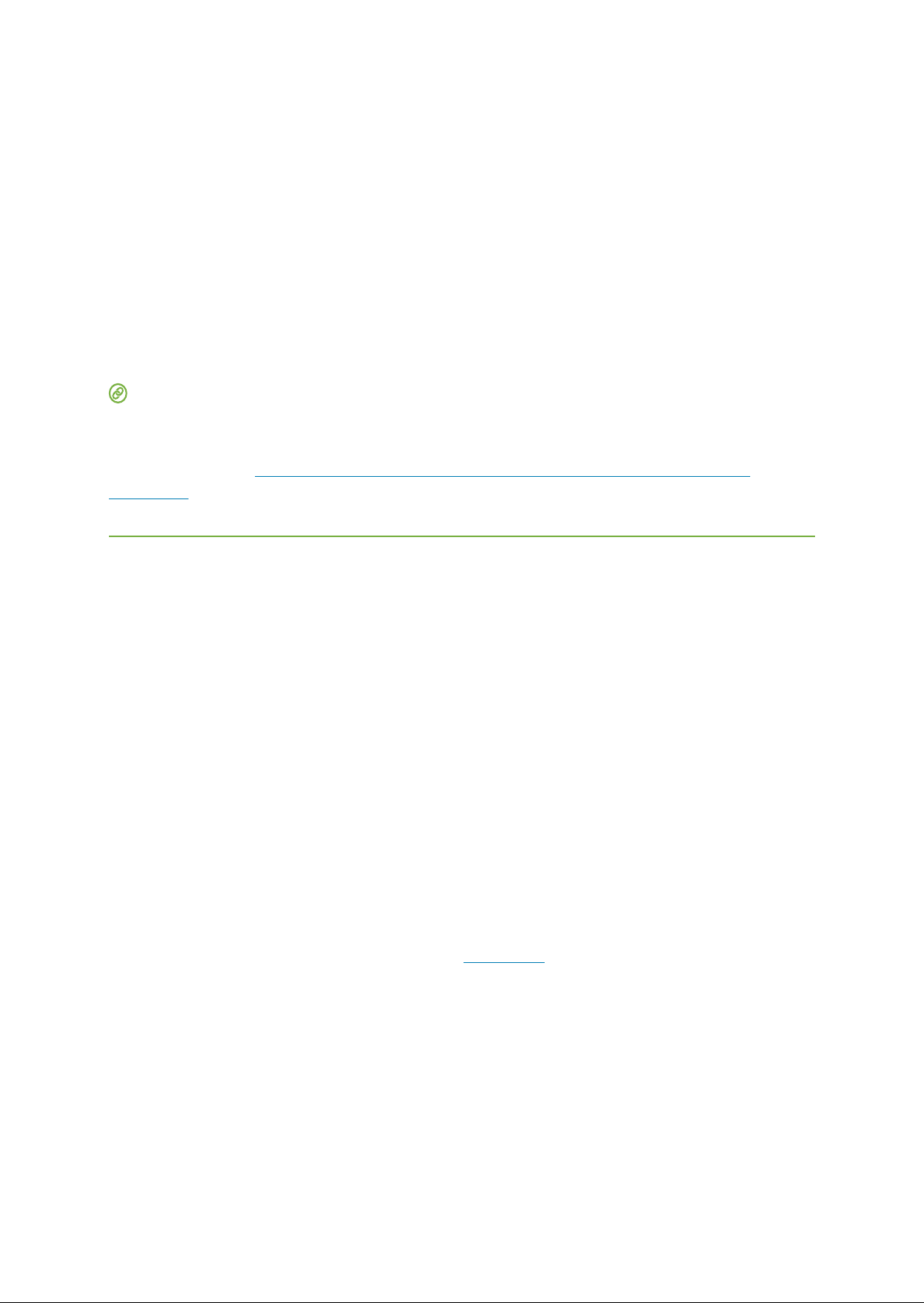

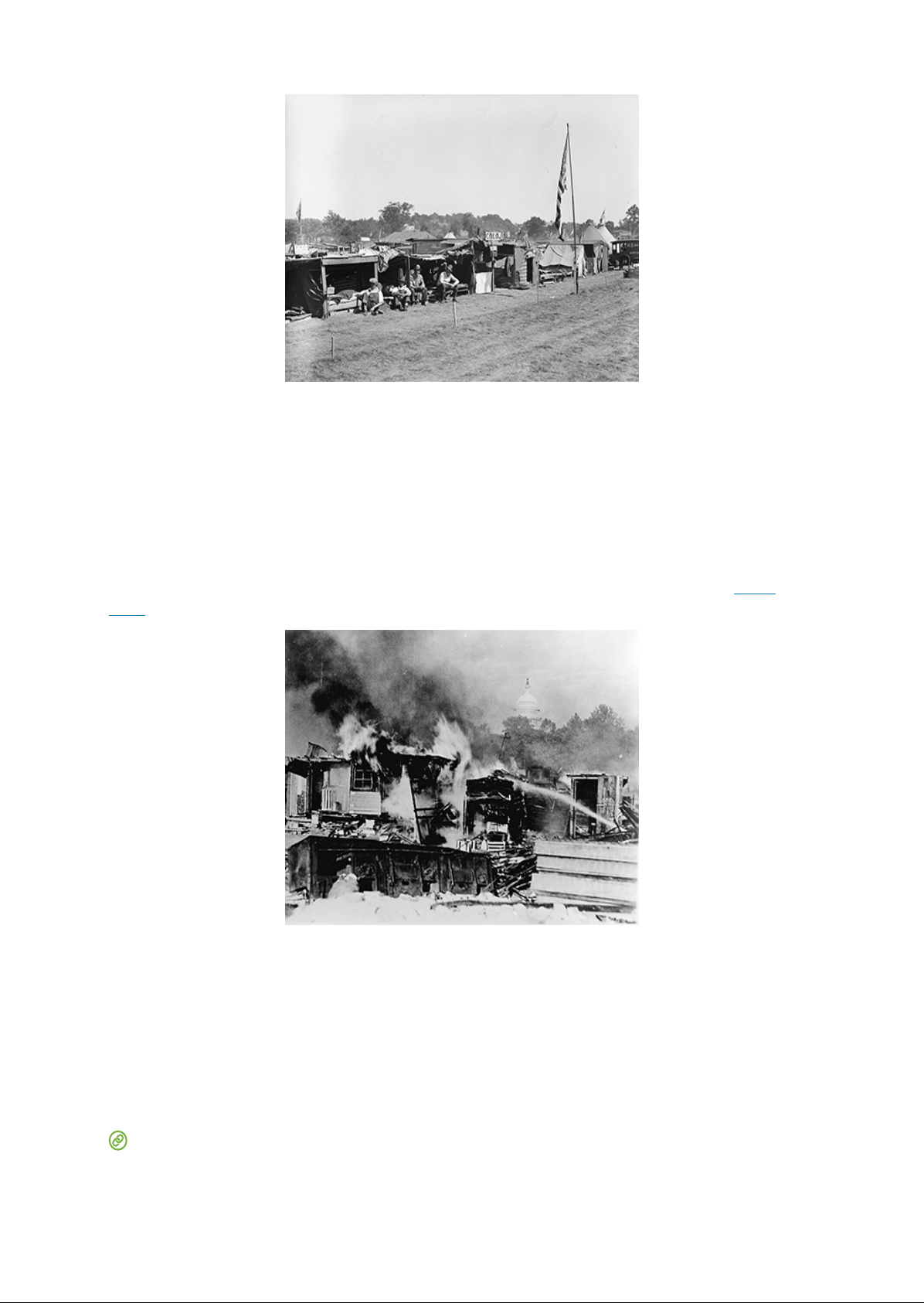

President Hoover Response 679 of work by United States Farm Security Administration ) FRUSTRATION AND PROTEST A BAD SITUATION GROWS WORSE FOR HOOVER Desperation and frustration often create emotional responses , and the Great Depression was no exception . Throughout , companies trying to stay sharply cut worker wages , and , in response , workers protested in increasingly bitter strikes . As the Depression unfolded , over 80 percent of automotive workers lost their jobs . Even the typically prosperous Ford Motor Company laid off of its workforce . In 1932 , a major strike at the Ford Motor Company factory near Detroit resulted in over sixty injuries and four deaths . Often referred to as the Ford March , the event unfolded as a planned demonstration among unemployed Ford workers who , to protest their desperate situation , marched nine miles from Detroit to the company River Rouge plant in Dearborn . At the Dearborn city limits , local police launched tear gas at the roughly three thousand protesters , who responded by throwing stones and clods of dirt . When they reached the gates of the plant , protestors faced more police and , as well as private security guards . As the turned hoses onto the protestors , the police and security guards opened . In addition to those killed and injured , police arrested protestors . One week later , sixty thousand mourners attended the public funerals of the four victims of what many protesters labeled police brutality . The event set the tone for worsening labor relations in the . Farmers also organized and protested , often violently . The most notable example was the Farm Holiday Association . Led by Milo Reno , this organization held sway among farmers in Iowa , Nebraska , Wisconsin , Minnesota , and the . Although they never comprised a majority of farmers in any of these states , their public actions drew press attention nationwide . Among their demands , the association sought a federal government plan to set agricultural prices high enough to cover the farmers costs , as well as a government commitment to sell any farm surpluses on the world market . To achieve their goals , the group called for farm holidays , during which farmers would neither sell their produce nor purchase any other goods until the government met their demands . However , the greatest strength of the association came from the unexpected and actions of its members , which included barricading roads into markets , attacking nonmember farmers , and destroying their produce . Some members even raided small town stores , destroying produce on the shelves . Members also engaged in penny auctions , bidding pennies on foreclosed farm land and threatening any potential buyers with bodily harm if they competed in the sale . Once they won the auction , the association returned the land to the original owner . In Iowa , farmers threatened to hang a local judge if he signed any more farm foreclosures . At least one death occurred as a direct result of these protests before they waned following the election of Franklin Roosevelt . One of the most notable protest movements occurred toward the end of Hoover presidency and centered on the Bonus Expeditionary Force , or Bonus Army , in the spring of 1932 . In this protest , approximately thousand World War I veterans marched on Washington to demand early payment of their veteran bonuses , which were not due to be paid until 1945 . The group camped out in vacant federal buildings and set up camps in Flats near the Capitol building Figure 2510 .

680 25 Brother , can Vou Spare a Dime ?

The Great Depression , FIGURE In the spring of 1932 , World War I veterans marched on Washington and set up camps in Flats , remaining there for weeks . credit Library of Congress ) Many veterans remained in the city in protest for nearly two months , although the Senate rejected their request in July . By the middle of that month , Hoover wanted them gone . He ordered the police to empty the buildings and clear out the camps , and in the exchange that followed , police into the crowd , killing two veterans . Fearing an armed uprising , Hoover then ordered General Douglas MacArthur , along with his aides , Dwight Eisenhower and George Patton , to forcibly remove the veterans from Flats . The ensuing raid proved catastrophic , as the military burned down the shantytown and injured dozens of people , including a infant who was killed when accidentally struck by a tear gas canister ( Figure 2511 ) FIGURE When the Senate denied early payment oftheir veteran bonuses , and Hoover ordered their makeshift camps cleared , the Bonus Army protest turned violent , cementing Hoover demise as a president . credit US . Department of Defense ) As Americans bore witness to photographs and newsreels of the Army forcibly removing veterans , Hoover popularity plummeted even further . By the summer of 1932 , he was largely a defeated man . His pessimism and failure mirrored that of the nation citizens . America was a country in desperate need in need of a charismatic leader to restore public as well as provide concrete solutions to pull the economy out of the Great Depression . CLICK AND EXPLORE Whether he truly believed it or simply thought the American people wanted to hear it , Hoover continued to Access for free at .

The Depths of the Great Depression 681 state publicly that the country was getting back on track . Listen as he speaks about the Success of , edu 5062 at a campaign stop in Detroit , Michigan on October 22 , 1932 . The Depths of the Great Depression LEARNING OBJECTIVES By the end ofthis section , you will be able to challenges that everyday Americans faced as a of the Great Depression and analyze the government initial unwillingness to provide assistance Explain the particular challenges that African Americans faced during the crisis unique challenges that farmers in the Great Plains faced period Explain the Great Depression influence on American values anc popular culture From industrial strongholds to the rural Great Plains , from factory workers to farmers , the Great Depression affected millions . In cities , as industry slowed , then sometimes stopped altogether , workers and joined , or sought out other charitable efforts . With ed government relief efforts , private charities tried to help , but they were unable to match the pace of demand . In rural areas , farmers suffered still more . In some parts of the country , prices for crops dropped so precipitously that farmers could not earn enough to pay their mortgages , losing their farms to foreclosure . In the Great Plains , one of the worst droughts in history left the land barren and for growing even minimal ood to live on . The country most vulnerable populations , such as children , the elderly , and those subject to discrimination , like African Americans , were the hardest hit . Most White Americans felt entitled to what few jobs were available , leaving African Americans unable to work , even in tie jobs once considered their domain . In all , the economic misery was unprecedented in the country history . STARVING TO DEATH By the end of 1932 , the Great Depression had affected some sixty million people , most ofwhom wealthier Americans perceived as the deserving poor . Yet , at the time , federal efforts to help those in need were extremely limited , and national charities had neither the capacity nor the will to elicit the response required to address the problem . The American Red Cross did exist , but Chairman John Barton Payne contended that unemployment was not an Act of God but rather an Act of Man , and therefore refused to get involved in widespread direct relief efforts . Clubs like the Elks tried to provide food , as did small groups of individually organized college students . Religious organizations remained on he front lines , offering food and shelter . In larger cities , and soup lines became a common sight . At one count in 1932 , there were as many as in New York City . Despite these efforts , however , people were destitute and ultimately starving . would run through any savings , if they were lucky enough to have any . Then , the few who had insurance would cash out their policies . Cash surrender payments of individual insurance policies tripled in he three years of the Great Depression , with insurance companies issuing total payments in excess of billion in 1932 alone . When those funds were depleted , people would borrow from family and friends , anc when they could get no more , they would simply stop paying rent or mortgage payments . When evicted , they would move in with relatives , whose own situation was likely only a step or two behind . The added burden of additional people would speed along that family demise , and the cycle would continue . This situation ed downward , and did so quickly . Even as late as 1939 , over 60 percent of rural households , and 82 percent of farm families , were as impoverished . In larger urban areas , unemployment levels exceeded the national average , with over half a million unemployed workers in Chicago , and nearly a million in New York City . and soup kitchens were packed , serving as many as thousand meals daily in New City alone . Over thousand New York citizens were homeless by the end of 1932 . Children , in particular , felt the brunt of poverty . Many in coastal cities would roam the clocks in search of

682 25 Brother , Can Vou Spare a Dime ?

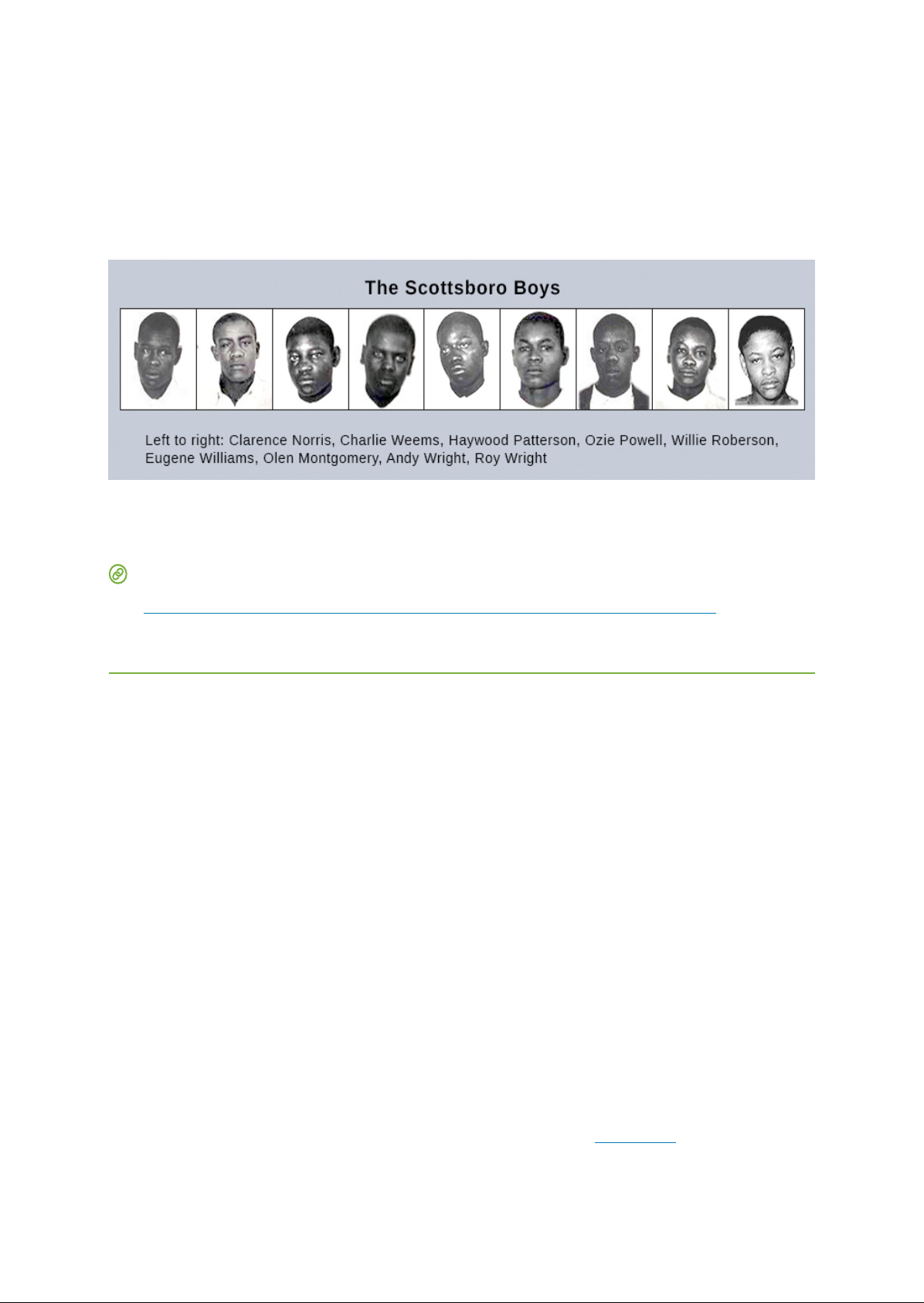

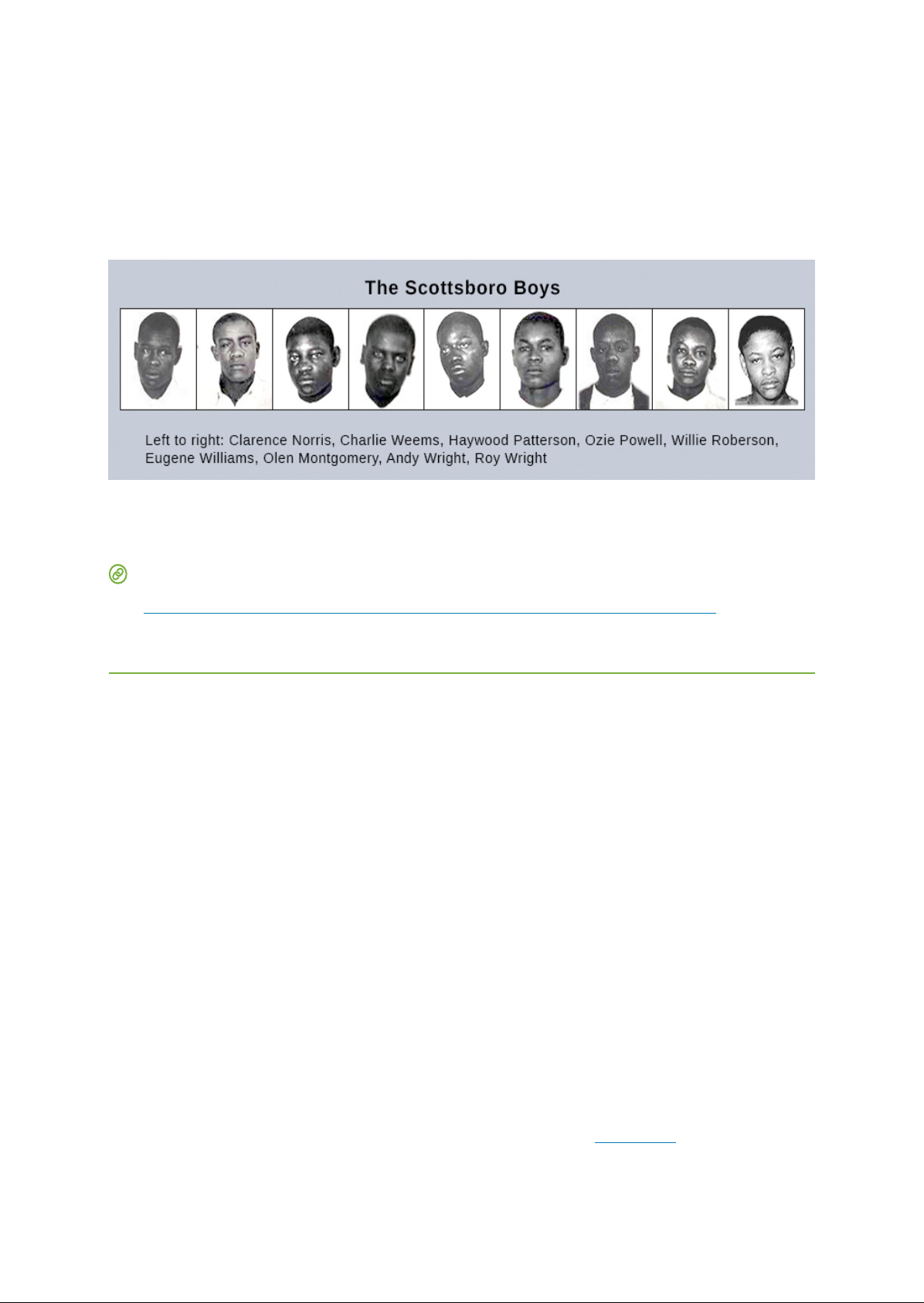

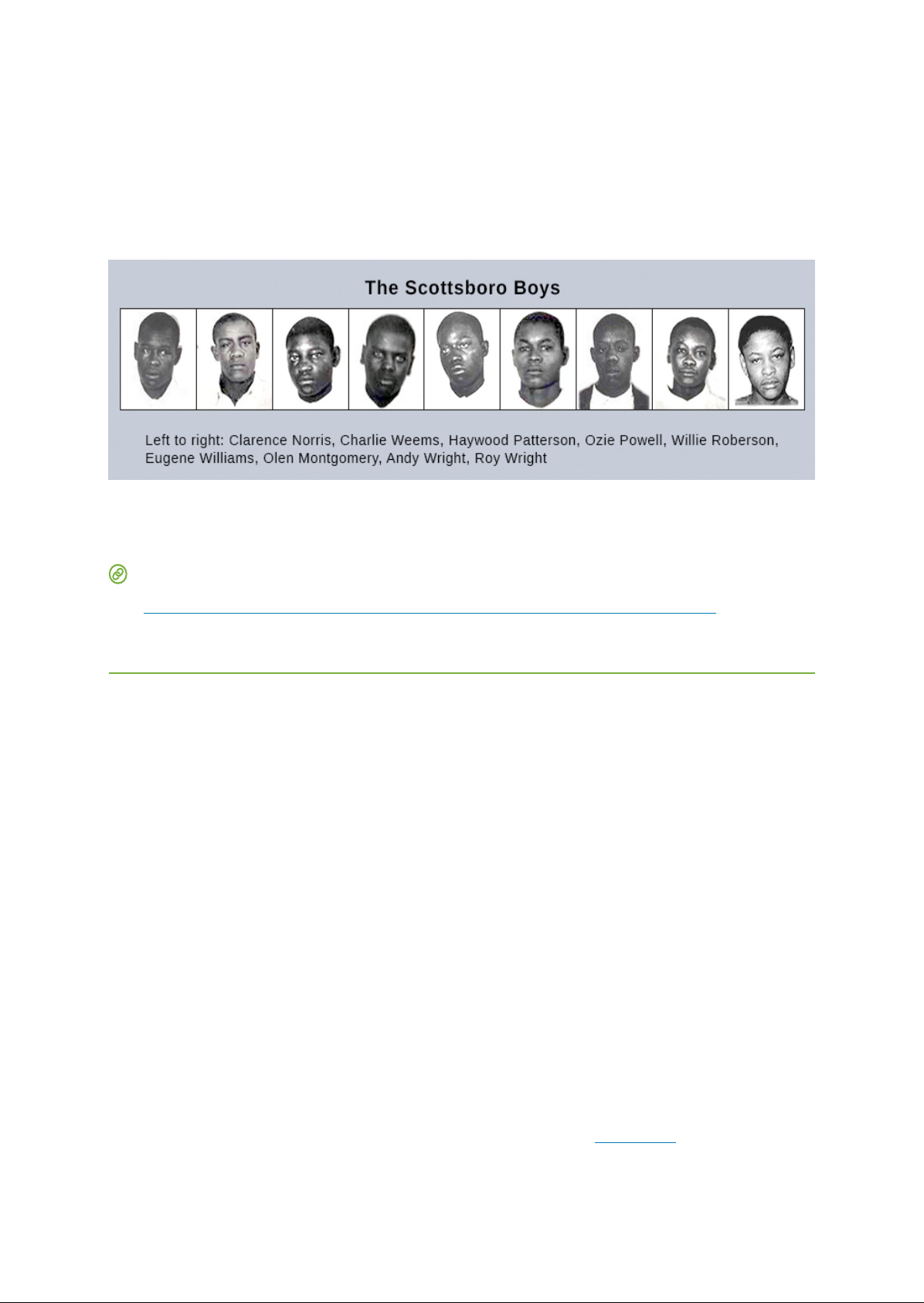

The Great Depression , spoiled vegetables to bring home . Elsewhere , children begged at the doors of more neighbors , hoping for stale bread , table scraps , or raw potato peelings . Said one childhood survivor of the Great Depression , You get used to hunger . After the few days it does even hurt you just get weak . In 1931 alone , there were at least twenty documented cases of starvation in 1934 , that number grew to 110 . In rural areas where such documentation was lacking , the number was likely far higher . And while the middle class did not suffer from starvation , they experienced hunger as well . By the time Hoover left in 1933 , the poor survived not on relief efforts , but because they had learned to be poor . A family with little food would stay in bed to save fuel and avoid burning calories . People began eating parts of animals that had normally been considered waste . They scavenged for scrap wood to burn in the furnace , and when electricity was turned off , it was not uncommon to try and tap into a neighbor wire . Family members swapped clothes sisters might take turns going to church in the one dress they owned . As one girl in a mountain town told her teacher , who had said to go home and get food , I ca . It my sisters turn to CLICK AND EXPLORE For his book on the Great Depression , Hard Times , author Studs interviewed hundreds of Americans from across the country . He subsequently selected over seventy interviews to air on a radio show that was based in Chicago . Visit Studs Conversations with America ( to listen to those interviews , during which participants on their personal hardships as well as on national events during the Great Depression . BLACK AND POOR AFRICAN AMERICANS AND THE GREAT DEPRESSION Most African Americans did not participate in the land boom and stock market speculation that preceded the crash , but that did not stop the effects of the Great Depression from hitting them particularly hard . Subject to continuing racial discrimination , Black people nationwide fared even worse than their White counterparts . As the prices for cotton and other agricultural products plummeted , farm owners paid workers less or simply laid them off . Landlords evicted sharecroppers , and even those who owned their land outright had to abandon it when there was no way to earn any income . In cities , African Americans fared no better Unemployment was rampant , and many White people felt that any available jobs should go to them . In some Northern cities , White employees would conspire to have African American workers to allow White workers access to their jobs . Even jobs traditionally held by Black workers , such as household servants or janitors , were now going to White people . By 1932 , approximately of all Black Americans were unemployed . Racial violence also began to rise . In the South , lynching became more common again , with documented lynchings in 1933 , compared to eight in 1932 . Since communities were preoccupied with their own hardships , and organizing civil rights efforts was a long , process , many resigned themselves to , or even ignored , this culture of racism and violence . Occasionally , however , an incident was notorious enough to gain national attention . One such incident was the case of the Boys ( Figure 2512 . In 1931 , nine Black boys , who had been riding the rails , were arrested for vagrancy and disorderly conduct after an altercation with some White travelers on the train . Two young White women , who had been dressed as boys and traveling with a group of White boys , came forward and said that the Black boys had raped them . The case , which was tried in , Alabama , illuminated decades of racial hatred and illustrated the injustice of the court system . Despite evidence that the women had not been raped at all , along with one of the women subsequently recanting her testimony , the jury quickly convicted the boys and sentenced all but one of them to death . The verdict broke through the veil of indifference toward the plight of African Americans , and protests erupted among newspaper editors , academics , and social reformers in the North . The Communist Party of the United States offered to handle the case and sought retrial the NAACP later joined in this effort . In all , the case was tried three separate times . The series of trials and retrials , appeals , and overturned Access for free at .

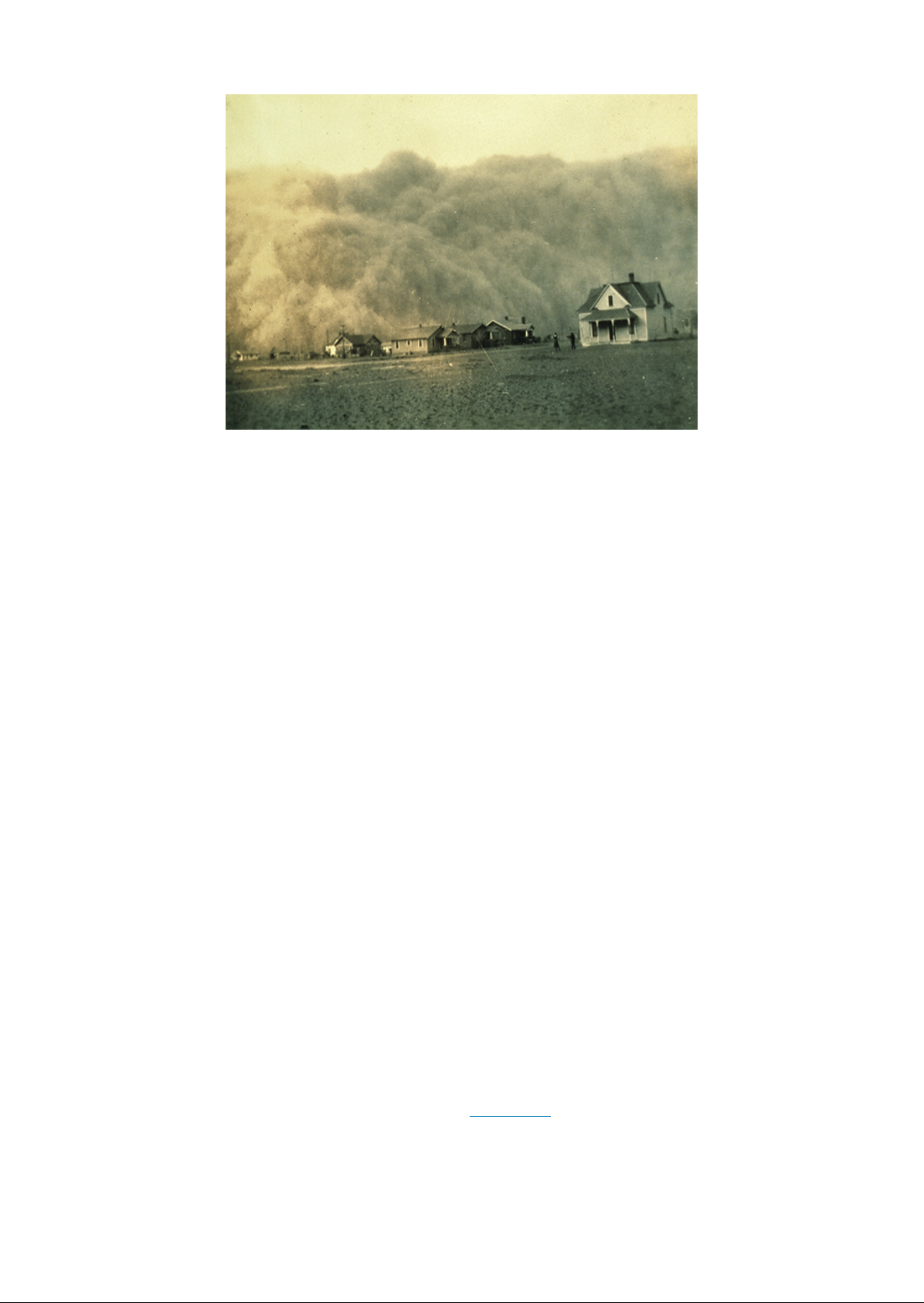

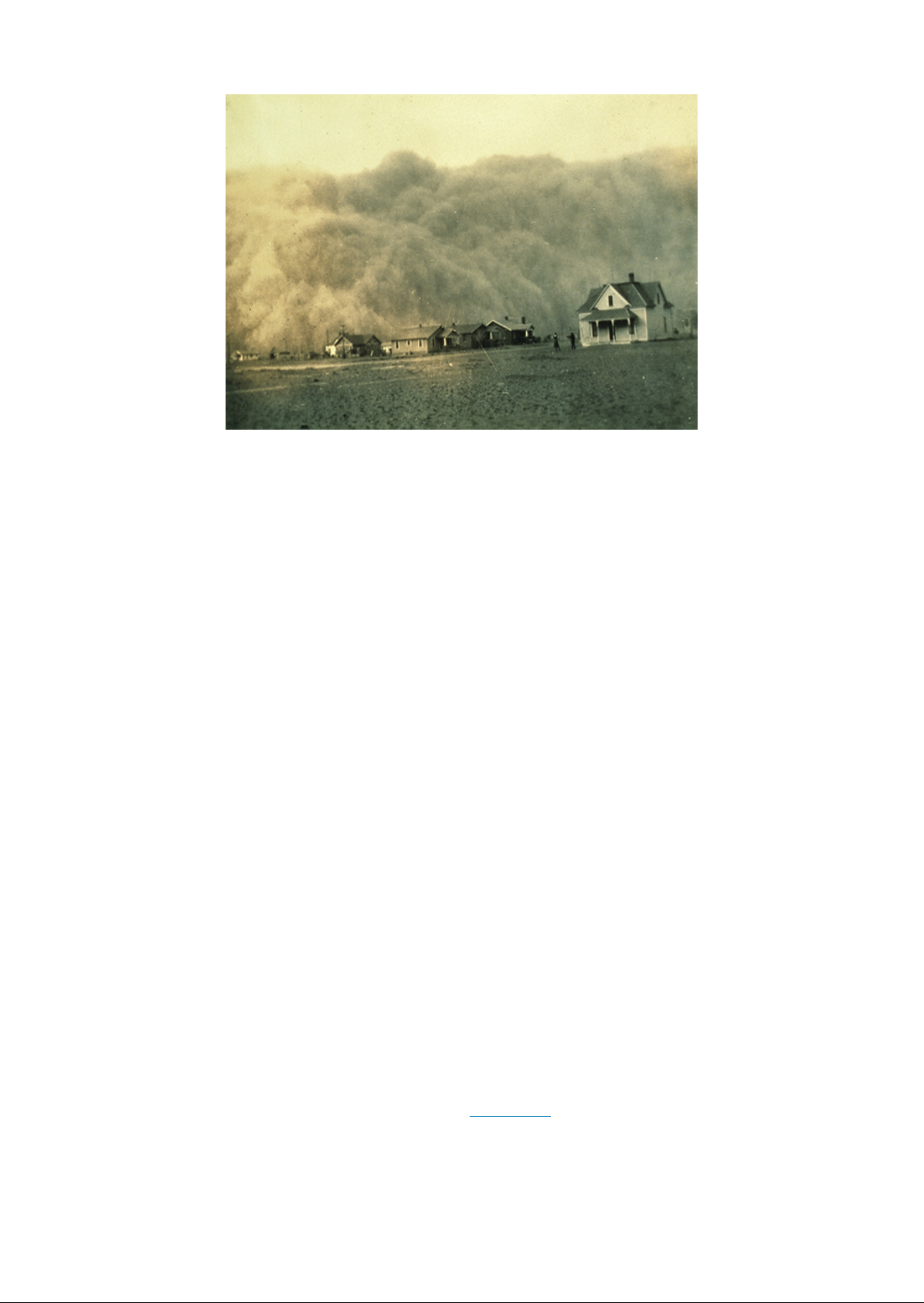

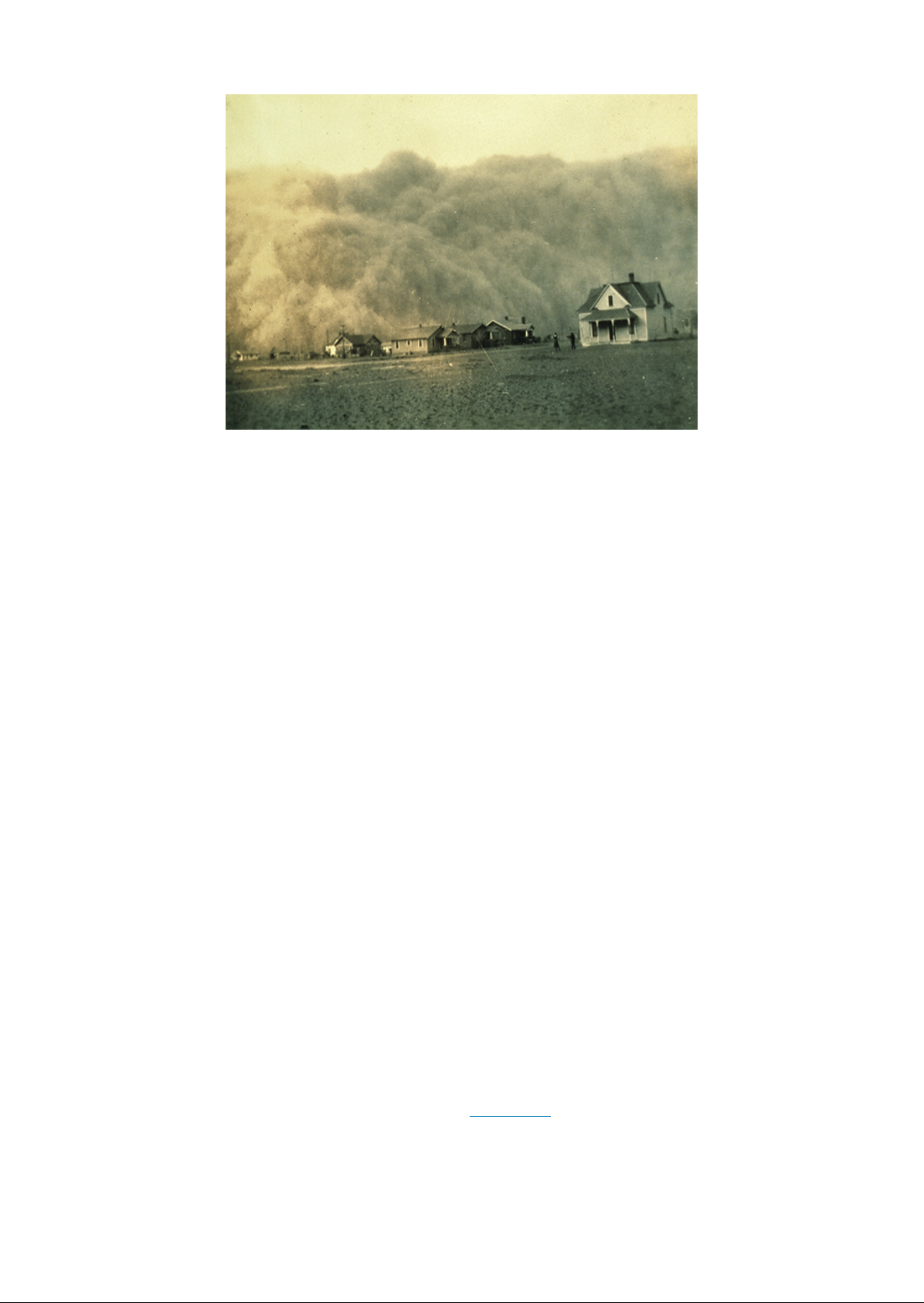

The Depths of the Great Depression 683 convictions shone a spotlight on a system that provided poor legal counsel and relied on juries . In October 1932 , the Supreme Court agreed with the Communist Party defense attorneys that the defendants had been denied adequate legal representation at the original trial , and that due process as provided by the Fourteenth Amendment had been denied as a result of the exclusion of any potential Black jurors . Eventually , most of the accused received lengthy prison terms and subsequent parole , but avoided the death penalty . The case ultimately laid some of the early groundwork for the modern American civil rights movement . Alabama granted posthumous pardons to all defendants in 2013 . The Boys Left to right Clarence Norris , Charlie Weems , Patterson , Powell . Willie . Eugene Williams , Olen Montgomery . Andy Wright , Roy Wright FIGURE The trial and conviction of nine African American boys in , Alabama , illustrated the numerous injustices of the American court system . Despite being falsely accused , the boys received lengthy prison terms and were not pardoned by the State of Alabama until 2013 . CLICK AND EXPLORE Read Voices from ( ifor the perspectives of both participants and spectators in the case , from the initial trial to the moment , in 1976 , when one of the women sued for slander . ENVIRONMENTAL CATASTROPHE MEETS ECONOMIC HARDSHIP THE DUST BOWL Despite the widely held belief that rural Americans suffered less in the Great Depression due to their ability to at least grow their own food , this was not the case . Farmers , ranchers , and their families suffered more than any group other than African Americans during the Depression . From the turn of the century through much of World War I , farmers in the Great Plains experienced prosperity due to unusually good growing conditions , high commodity prices , and generous government farming policies that led to a rush for land . As the federal government continued to purchase all excess produce for the war effort , farmers and ranchers fell into several bad practices , including mortgaging their farms and borrowing money against future production in order to expand . However , after the war , prosperity rapidly dwindled , particularly during the recession of 1921 . Seeking to recoup their losses through economies of scale in which they would expand their production even further to take full advantage of their available land and machinery , farmers plowed under native grasses to plant acre after acre of wheat , with little regard for the repercussions to the soil . Regardless of these misguided efforts , commodity prices continued to drop , plummeting in 1929 , when the price dropped from two dollars to forty cents per bushel . Exacerbating the problem was a massive drought that began in 1931 and lasted for eight terrible years . Dust storms through the Great Plains , creating huge , choking clouds that piled up in doorways and into homes through closed windows . Even more quickly than it had boomed , the land of agricultural opportunity went bust , due to widespread overproduction and overuse of the land , as well as to the harsh weather conditions that followed , resulting in the creation of the Dust Bowl ( Figure .

684 25 Brother , can Vou Spare a Dime ?

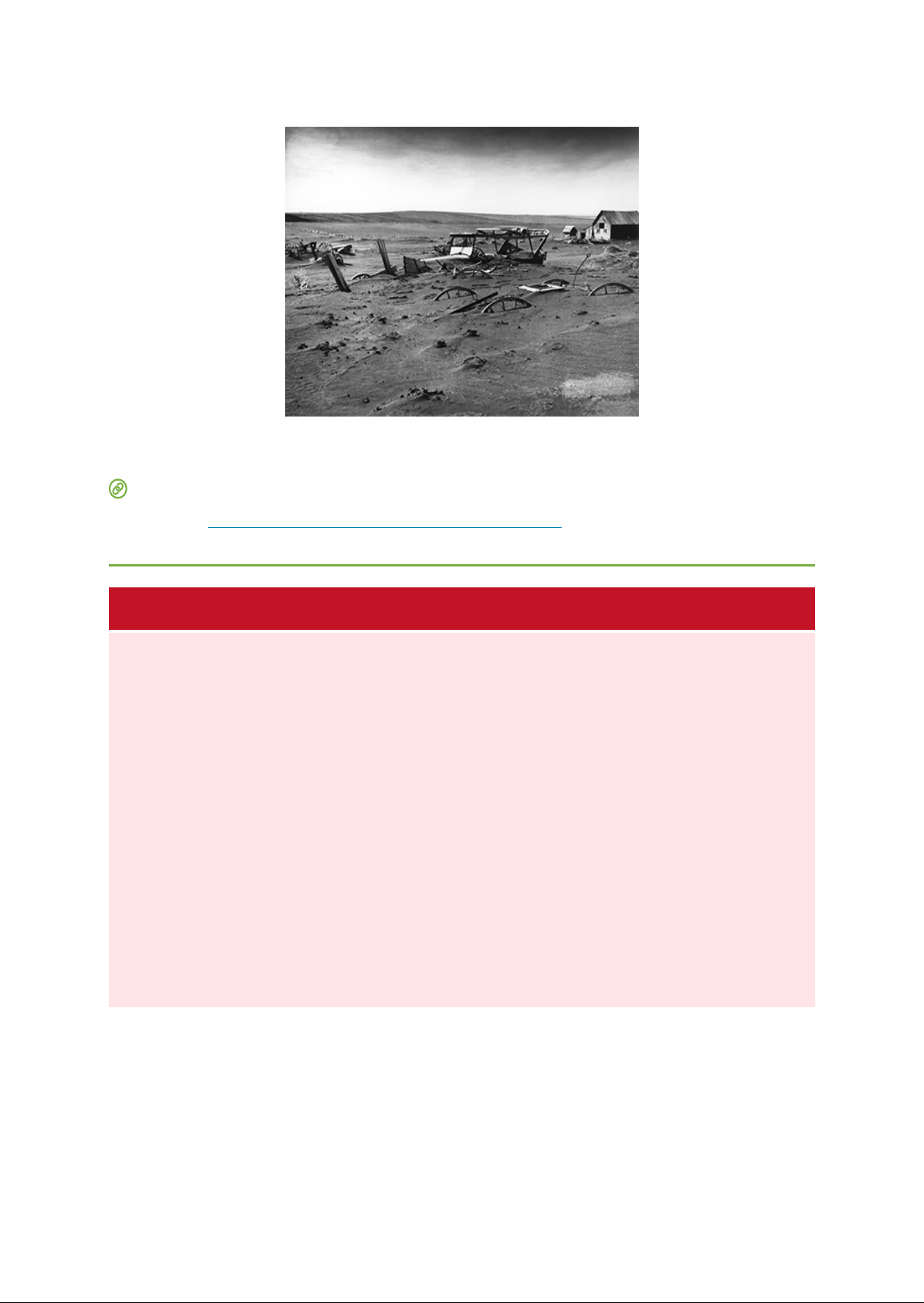

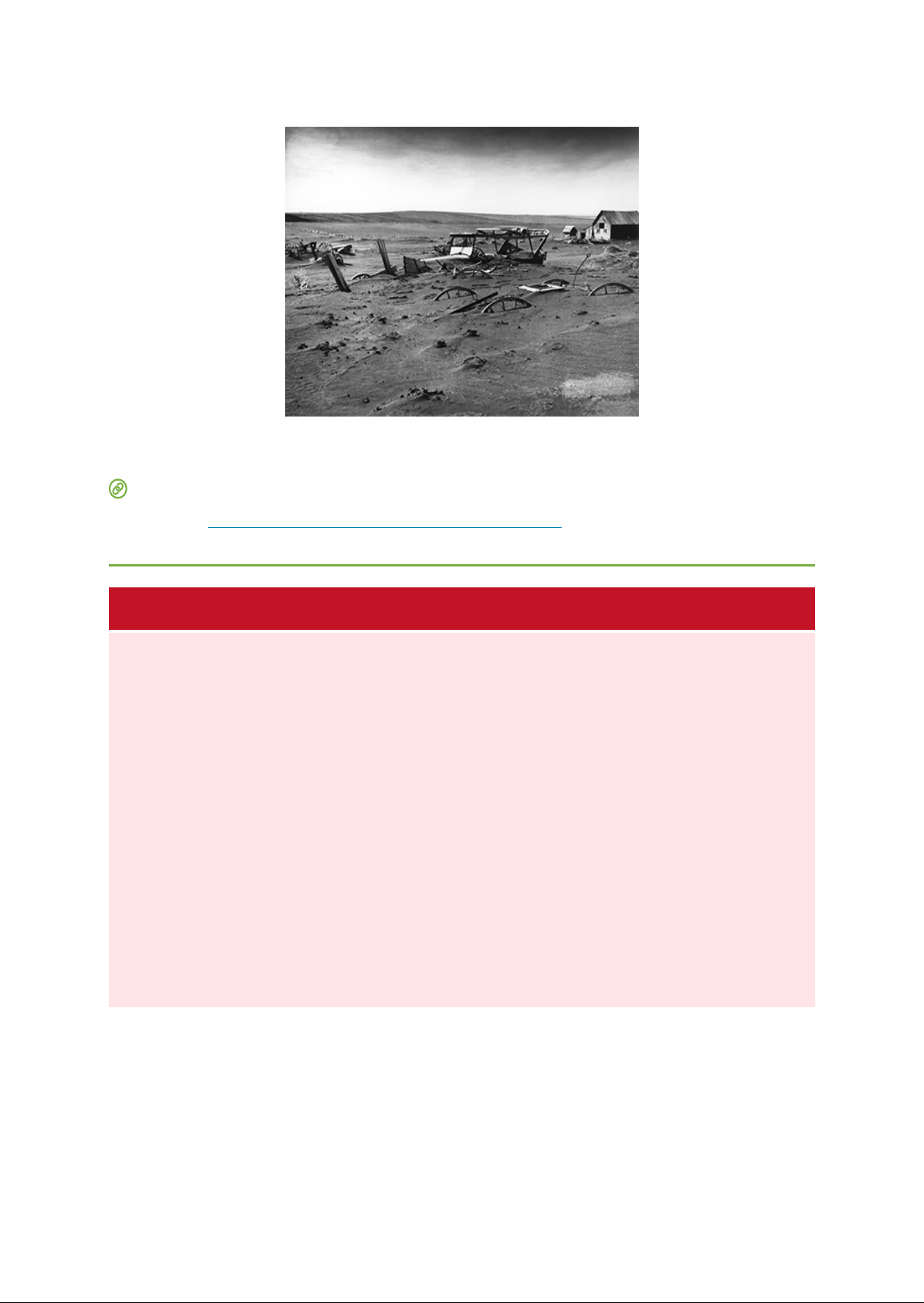

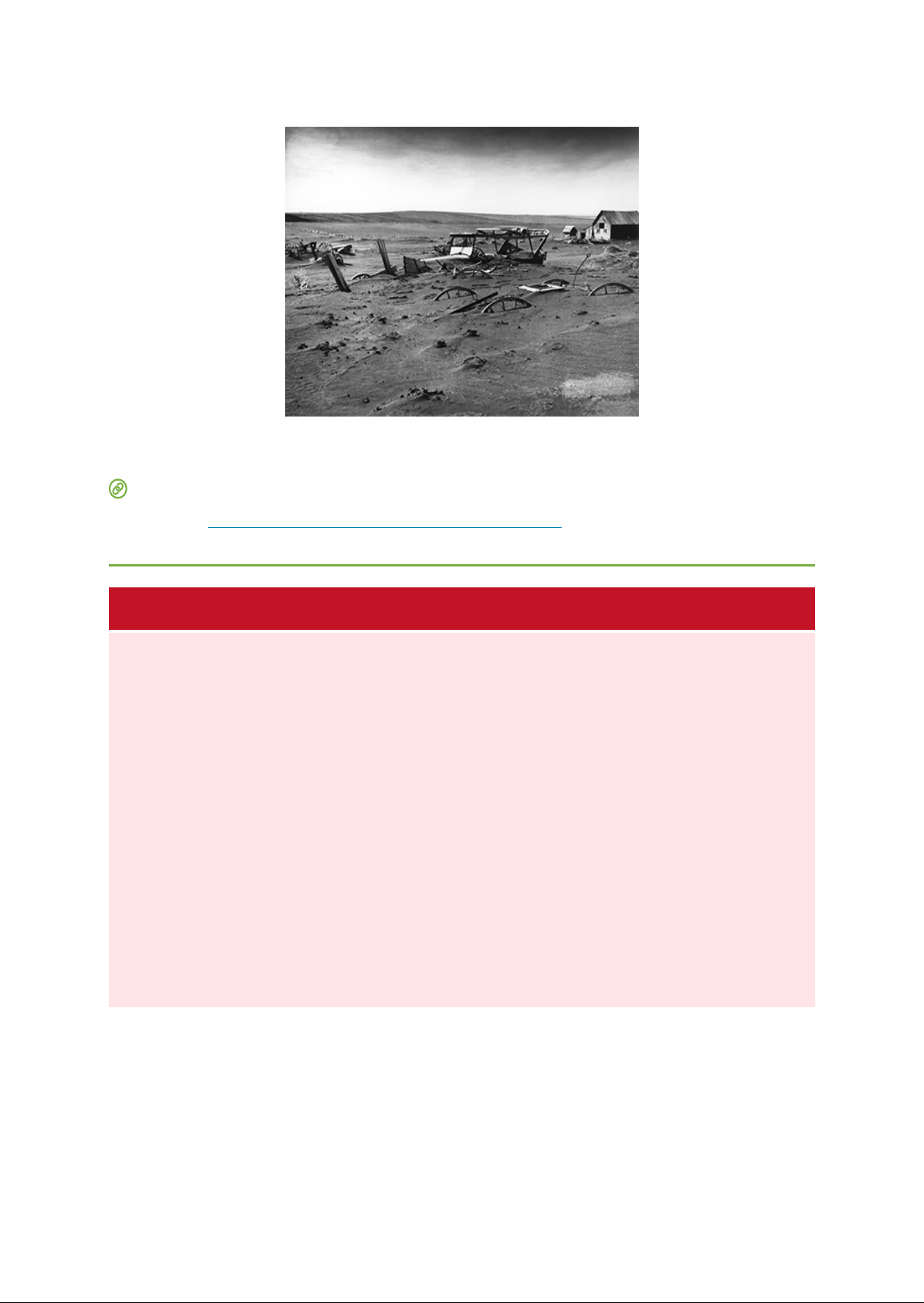

The Great Depression , FIGURE The dust storms that blew through the Great Plains were epic in scale . Drifts of dirt piled up against doors and windows . People wore goggles and tied rags over their mouths to keep the dust out . credit US . National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration ) Livestock died , or had to be sold , as there was no money for feed . Crops intended to feed the family withered and died in the drought . Terrifying dust storms became more and more frequent , as black blizzards of dirt blew across the landscape and created a new illness known as dust pneumonia . In 1935 alone , over 850 million tons of topsoil blew away . To put this number in perspective , geologists estimate that it takes the earth hundred years to naturally regenerate one inch of topsoil yet , just one dust storm could destroy a similar amount . In their desperation to get more from the land , farmers had stripped it of the delicate balance that kept it healthy . Unaware of the consequences , they had moved away from such traditional practices as crop rotation and allowing land to regain its strength by permitting it to lie fallow between plantings , working the land to death . For farmers , the results were catastrophic . Unlike most factory workers in the cities , in most cases , farmers lost their homes when they lost their livelihood . Most farms and ranches were originally mortgaged to small country banks that understood the dynamics of farming , but as these banks failed , they often sold rural mortgages to larger eastern banks that were less concerned with the of farm life . With the effects of the drought and low commodity prices , farmers could not pay their local banks , which in turn lacked funds to pay the large urban banks . Ultimately , the large banks foreclosed on the farms , often swallowing up the small country banks in the process . It is worth noting that of the thousand banks that closed between 1930 and 1932 , over 75 percent were country banks in locations with populations under . Given this dynamic , it is easy to see why farmers in the Great Plains remained wary of big city bankers . For farmers who survived the initial crash , the situation worsened , particularly in the Great Plains where years of overproduction and rapidly declining commodity prices took their toll . Prices continued to decline , and as farmers tried to stay , they produced still more crops , which drove prices even lower . Farms failed at an astounding rate , and farmers sold out at prices . One farm in Shelby , Nebraska was mortgaged at and sold for . of the entire state of Mississippi was auctioned off in a single day at a foreclosure auction in April 1932 . Not all farmers tried to keep their land . Many , especially those who had arrived only recently , in an attempt to capitalize on the earlier prosperity , simply walked away Figure . In Oklahoma , thousands of farmers packed up what they could and walked or drove away from the land they thought would be their future . They , along with other displaced farmers from throughout the Great Plains , became known as Okies . Okies were an emblem of the failure of the American breadbasket to deliver on its promise , and their story was made Access for free at .

The Depths of the Great Depression famous in John novel , The Grapes of Wrath . FIGURE As the Dust Bowl continued in the Great Plains , many had to abandon their land and equipment , as captured in this image from 1936 , taken in Dallas , South Dakota . credit United States Department of Agriculture ) CLICK AND EXPLORE Experience the Interactive Dust Bowl ( to see how decisions compounded to create peoples destiny . Click through to see what choices you would make and where that would take you . MY STORY Caroline Henderson on the Dust Bowl Now we are facing a fourth year of failure . There can be no wheat for us in 1935 in spite of all our careful and expensive work in preparing ground , sowing and our allocated acreage . Native grass pastures are permanently damaged , in many cases hopelessly ruined , smothered under by drifted sand . Fences are buried under banks and hard packed earth or undermined by the eroding action ofthe wind and lying flat on the ground . Less traveled roads are impassable , covered deep under by sand or the loam . Orchards , groves and cultivated for many years with patient care are dead or dying . Impossible it seems not to grieve that the work of hands should prove so perishable . Henderson , Shelton , Oklahoma , 1935 Much like other farm families whose livelihoods were destroyed by the Dust Bowl , Caroline Henderson describes a level of hardship that many Americans living in cities could never understand . Despite their hard work , millions of Americans were losing both their produce and their homes , sometimes in as little as eight hours , to environmental catastrophes . Lacking any other explanation , many began to question what they had done to incur God wrath . Note in particular Henderson references to dead , dying , and perishable , and contrast those terms with her depiction of the careful and expensive work undertaken by their own hands . Many simply could not understand how such a catastrophe could have occurred . CHANGING VALUES , CHANGING CULTURE In the decades before the Great Depression , and particularly in the 19205 , American culture largely the values of individualism , and material success through competition . Novels like Scott Fitzgerald The Great Gatsby and Sinclair Lewis wealth and the man in America , albeit in a critical fashion . In , many silent movies , such as Charlie Chaplin The Gold Rush , depicted the fable that Americans so loved . With the shift in fortunes , however , came a shift in values , and with it , a new cultural . The arts revealed a new emphasis on the welfare of the whole and the 685

686 25 Brother , can You Spare a Dime ?

The Great Depression , importance of community in preserving family life . While box sales declined at the beginning of the Depression , they quickly rebounded . Movies offered a way for Americans to think of better times , and people were willing to pay cents for a chance to escape , at least for a few hours . Even more than escapism , other at the close of the decade reflected on the sense of community and family values that Americans struggled to maintain throughout the entire Depression . John Ford screen version of The Grapes of Wrath came out in 1940 , portraying the haunting story of the family exodus from their Oklahoma farm to California in search of a better life . Their journey leads them to realize that they need to join a larger social to bettering the lives of all people . Tom says , Well , maybe it like says , a fella ain got a soul of his own , but on ' a piece of a one big soul that belongs to ever body . The greater lesson learned was one of the strength of community in the face of individual adversity . Another trope was that of the everyman against greedy banks and corporations . This was perhaps best portrayed in the movies of Frank Capra , whose Smith Goes to Washington was emblematic of his work . In this 1939 , Jimmy Stewart plays a legislator sent to Washington to out the term of a deceased senator While there , he corruption to ensure the construction of a boy camp in his hometown rather than a dam project that would only serve to line the pockets of a few . He ultimately engages in a , standing up to the power players to do what right . The Depression era was a favorite of Capra to depict in his , including It a Wonderful Life , released in 1946 . In this , Jimmy Stewart runs a savings and loan , which at one point faces a bank run similar to those seen in . In the end , community support helps Stewart retain his business and home against the unscrupulous actions of a wealthy banker who sought to bring ruin to his family . AMERICANA Brother , Can You Spare a Dime ?

They used to tell me I was buildinga dream , and so I followed the mob When there was earth to plow or guns to bear , I was always there , right on the job They used to tell me I was building a dream , with peace and glory ahead Why should I be standing in line , just waiting for bread ?

Once I built a railroad , I made it run , made it race against time Once I built a railroad , now it done , Brother , can you spare a dime ?

Once I built a tower up to the sun , brick and rivet and lime Once I built a tower , now it done , Brother , can you spare a dime ?

and Yip Brother , Can You Spare a Dime ?

appeared in 1932 , written for the Broadway musical by Jay , a composer who based the song music on a Russian lullaby , and Edgar Yip , a lyricist who would go on to win an Academy Award for the song Over the Rainbow from The Wizard of 02 ( 1939 ) With its lyrics speaking to the plight of the common man during the Great Depression and the refrain appealing to the same sense of community in the of Frank Capra , Brother , Can You Spare a Dime ?

quickly became the de facto anthem ofthe Great Depression . Recordings by Bing Crosby , Al Jolson , and Rudy all enjoyed tremendous popularity in the 19305 . CLICK AND EXPLORE For more on Brother Can You Spare a Dime ?

and the Great Depression , visit li to explore the Kennedy Center digital resources and learn the Story Behind the Access for free at .

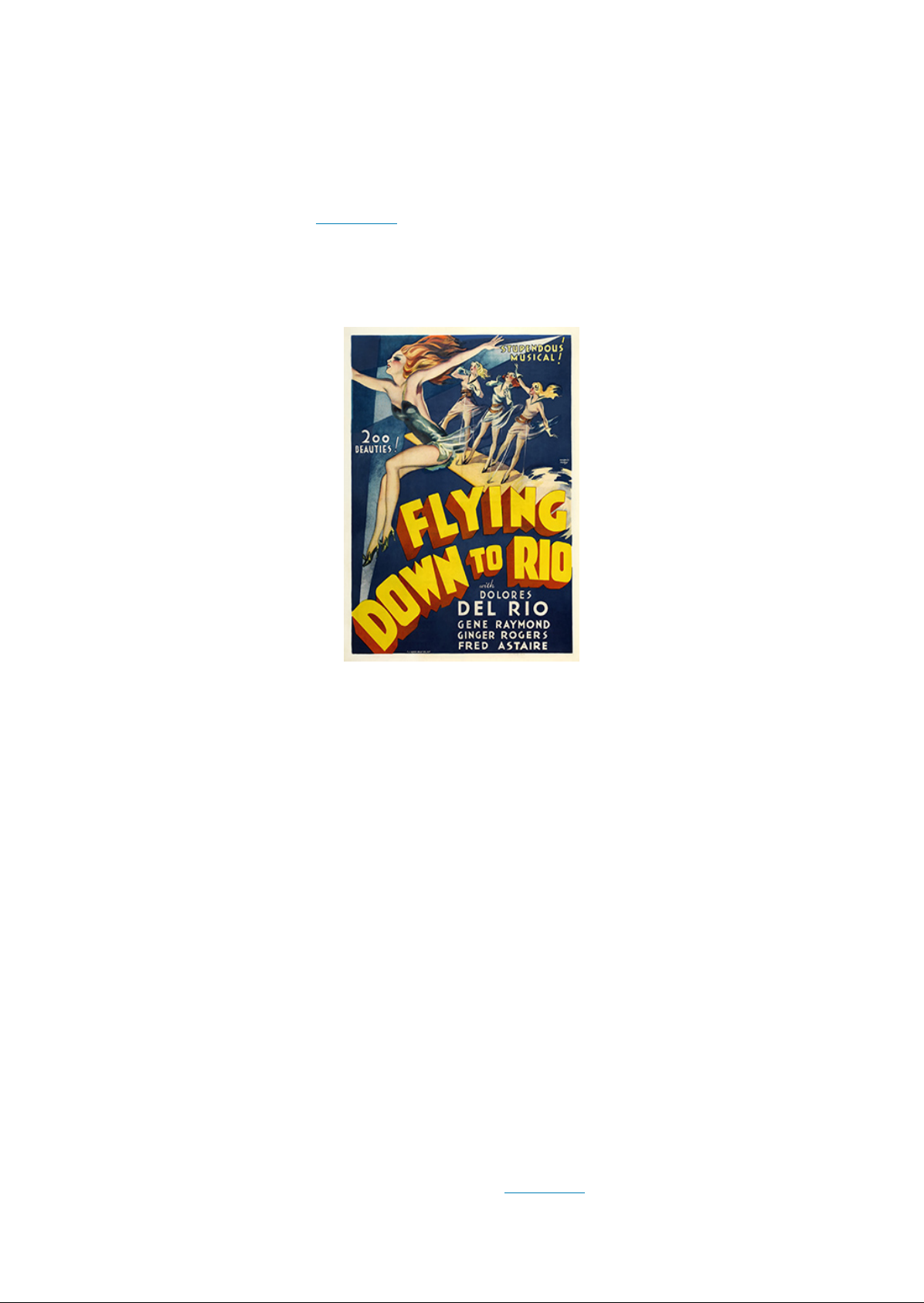

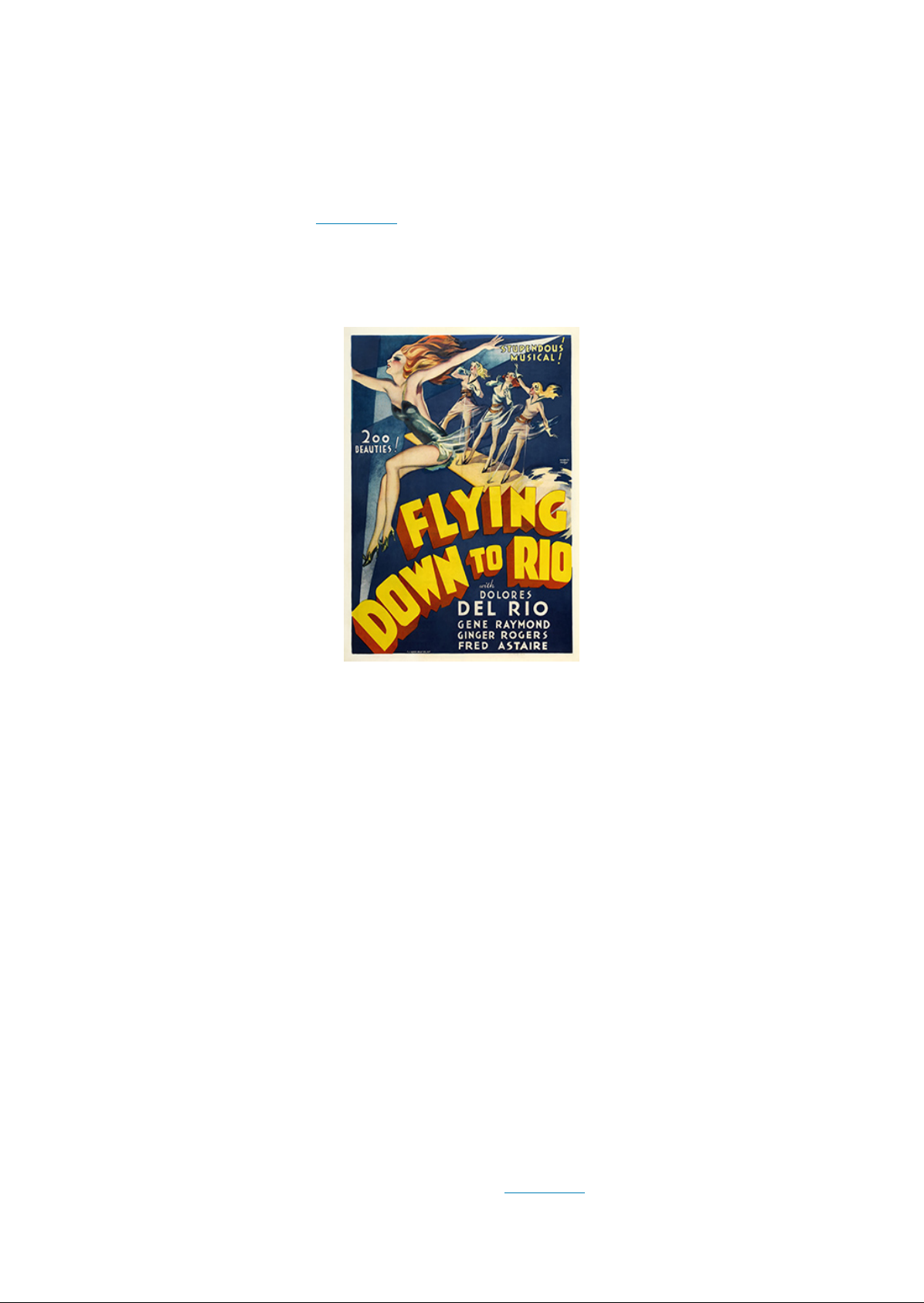

Assessing the Hoover Years on the Eve of the New Deal 687 Finally , there was a great deal of pure escapism in the popular culture of the Depression . Even the songs found in reminded many viewers of the bygone days of prosperity and happiness , from Al and Henry Warren hit We in the Money to the popular Happy Days are Here Again . The latter eventually became the theme song of Franklin Roosevelt 1932 presidential campaign . People wanted to forget their worries and enjoy the madcap antics of the Marx Brothers , the youthful charm of Shirley Temple , the dazzling dances of Fred and Ginger Rogers ( Figure 2515 , or the comforting morals of the Andy . The Hardy in all , produced by from 1936 to Judy Garland and Mickey Rooney , and all followed the adventures of a judge and his son . No matter what the challenge , it was never so big that it could not be solved with a musical production put on by the neighborhood kids , bringing together friends and family members in a warm display of community values . DE ) LORE DEL RIO GENE RAYMOND GINGER ROGERS FRED FIGURE Flying Down to Rio ( 1933 ) was the first motion picture to feature the immensely popular dance duo of Fred and Ginger Rogers . The pair would go on to star in nine more Hollywood musicals throughout the and . All of these movies reinforced traditional American values , which suffered during these hard times , in part due to declining marriage and birth rates , and increased domestic violence . At the same time , however , they an increased interest in sex and sexuality . While the birth rate was dropping , surveys in Fortune magazine in found that of college students favored birth control , and that 50 percent of men and 25 percent of women admitted to premarital sex , continuing a trend among younger Americans that had begun to emerge in the 19205 . Contraceptive sales soared during the decade , and again , culture this shift . Blonde bombshell Mae West was famous for her sexual innuendoes , and her persona was hugely popular , although it got her banned on radio broadcasts throughout the Midwest . Whether West or Garland , Chaplin or Stewart , American continued to be a barometer of American values , and their challenges , through the decade . Assessing the Hoover Years on the Eve of the New Deal LEARNING OBJECTIVES By the end ofthis section , you will be able to Identify the successes and failures of Herbert Hoover presidency Determine the fairness and accuracy of assessments of Hoover presidency As so much of the Hoover presidency is circumscribed by the onset of the Great Depression , one must be careful in assessing his successes and failures , so as not to attribute all blame to Hoover Given the suffering that many Americans endured between the fall of 1929 and Franklin Roosevelt inauguration in the spring of 1933 , it is easy to lay much of the blame at Hoover doorstep Figure 2516 . However , the extent to which

688 25 Brother , Can Vou Spare a Dime ?

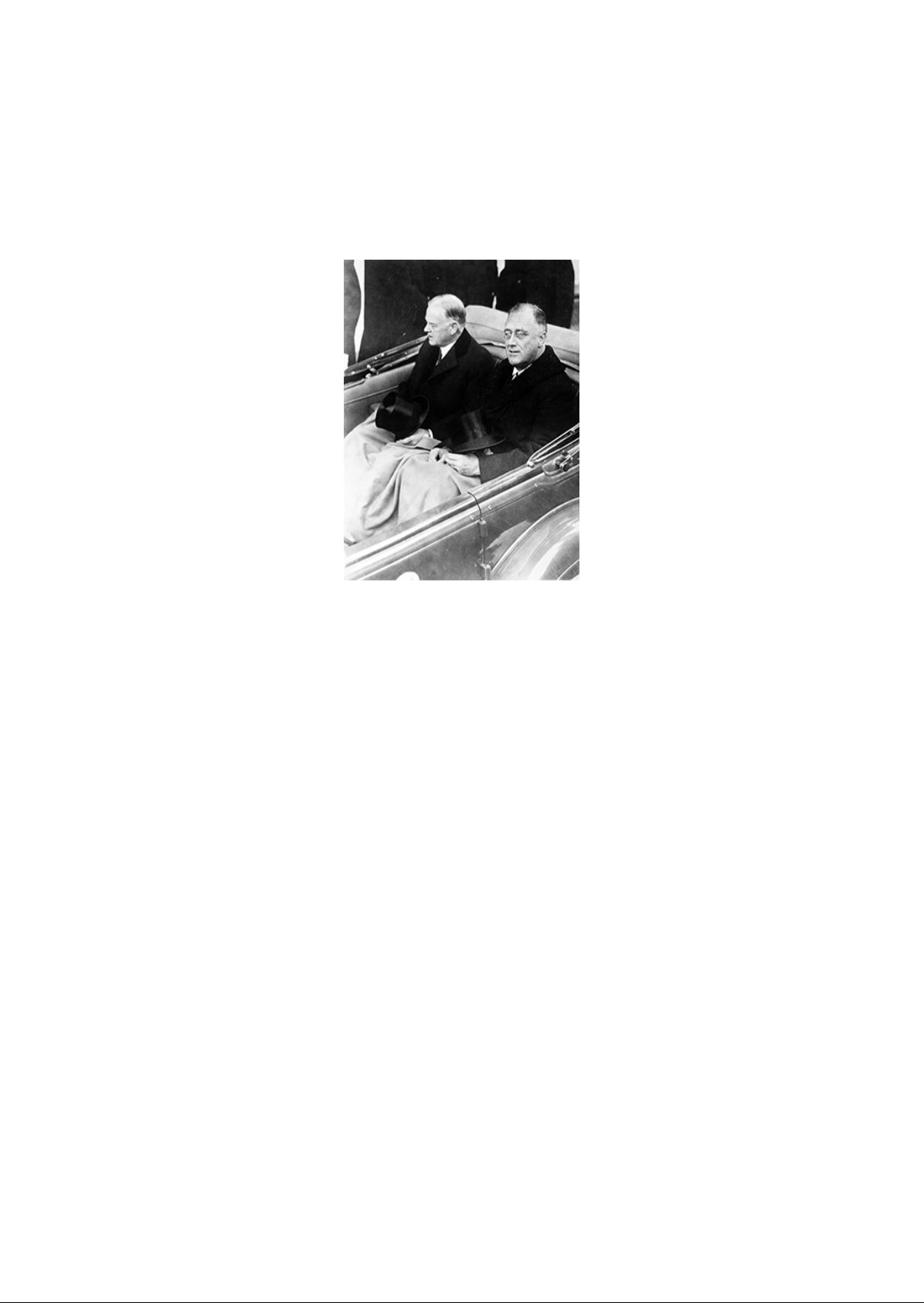

The Great Depression , Hoover was constrained by the economic circumstances unfolding well before he assumed offers a few mitigating factors . Put simply , Hoover did not cause the stock market crash . However , his stubborn adherence to a questionable belief in American individualism , despite mounting evidence that people were starving , requires that some blame be attributed to his policies ( or lack thereof ) for the depth and length of the Depression . Yet , Hoover presidency was much more than simply combating the Depression . To assess the extent of his inability to provide meaningful national leadership through the darkest months of the Depression , his other policies require consideration . FIGURE Herbert Hoover ( left ) had the misfortune to be a president elected in prosperity and subsequently tasked with leading the country through the Great Depression . His unwillingness to face the harsh realities of widespread unemployment , farm foreclosures , business failures , and bank closings made him a deeply unpopular president , and he lost the 1932 election in a landslide to Franklin , Roosevelt ( right ) credit Architect ofthe Capitol ) FOREIGN POLICY Al hough it was a relatively quiet period for diplomacy , Hoover did help to usher in a period of positive re , with several Latin American neighbors . This would establish the basis for Franklin Roosevelt Good Neighbor policy . After a goodwill tour of Central American countries immediately following his election in 1928 , Hoover shaped the subsequent Clark in largely re the previous Roosevelt Corollary , establishing a basis for unlimited American military intervention throughout Latin America . To the contrary , through the memorandum , Hoover asserted that greater emphasis should be placed upon the older Monroe Doctrine , in which the pledged assistance to her Latin American neighbors should any European powers interfere in Western Hemisphere affairs . Hoover further strengthened re to the south by withdrawing American troops from Haiti and Nicaragua . Additionally , he outlined wi Secretary of State Henry the Doctrine , which announced that the United States would never recognize claims to territories seized by force ( a direct response to the recent Japanese invasion of Manchuria ) Ot 181 diplomatic overtures met with less success for Hoover . Most notably , in an effort to support the American economy during the early stages of the Depression , the president signed into law the Tariff in 1930 . The law , which raised tariffs on thousands of imports , was intended to increase sales goods , but predictably angered foreign trade partners who in turn raised their tariffs on American imports , thus shrinking international trade and closing additional markets to desperate American manufacturers . As a result , the global depression worsened further . A similar attempt to spur the world economy , known as the Hoover Moratorium , likewise met with great opposition and little economic . Issued in 1931 , the moratorium called for a halt to World War I reparations to be paid by Germany to France , as well as forgiveness Access for free at .