America's War for Independence, 1775-1783

Explore the America's War for Independence, 1775-1783 study material pdf and utilize it for learning all the covered concepts as it always helps in improving the conceptual knowledge.

America's War for Independence, 1775-1783 PDF Download

America War for Independence , FIGURE This famous 1819 painting by John Trumbull shows members of the committee entrusted with drafting the Declaration of Independence work to the Continental Congress in 1776 . Note the British flags on the wall . Separating from the British Empire proved to be very difficult as the colonies and the Empire were linked with strong cultural , historical , and economic bonds forged over several generations . CHAPTER OUTLINE Britain Strategy and Its Consequences The Early Years of the Revolution War in the South Identity during the American Revolution INTRODUCTION By the , Great Britain ruled a vast empire , with its American colonies producing useful raw materials and consuming British goods . From Britain perspective , it was inconceivable that the colonies would wage a successful war for independence in 1776 , they appeared weak and disorganized , no match for the Empire . Yet , although the Revolutionary War did indeed drag on for eight years , in 1783 , the thirteen colonies , now the United States , ultimately prevailed against the British . The Revolution succeeded because colonists from diverse economic and social backgrounds united in their opposition to Great Britain . Although thousands of colonists remained loyal to the crown and many others preferred to remain neutral , a sense of community against a common enemy prevailed among Patriots . The signing of the Declaration of Independence ire oi the spirit of that common cause .

140 America War for Independence , Representatives asserted That these United Colonies are , and of Right ought to be Free and Independent States that they are Absolved from all Allegiance to the British Crown , And for the support of this Declaration , we mutually pledge to each other our Lives , our Fortunes and our sacred Honor . Britain Strategy and Its Consequences LEARNING OBJECTIVES By the end ofthis section , you will be able to Explain how Great Britain response to the destruction of a British shipment of tea in Boston Harbor in 1773 set the stage for the Revolution Describe the beginnings of the American Revolution Bottles of Lexington American and Concord forces defeat , British win General I The United States costly victory Burgoyne at ' and Great Britain at Battle of the Battle sign the Bunker Hill of Saratoga ( treaty of Paris 1775 1777 1783 I 1776 1781 ' Thomas Paine Lord ' publishes surrenders to ' Common Sense American and , Continental French . Congress signs at Yorktown Declaration of Independence , July FIGURE Great Britain pursued a policy of law and order when dealing with the crises in the colonies in the late and . Relations between the British and many American Patriots worsened over the decade , culminating in an unruly mob destroying a fortune in tea by dumping it into Boston Harbor in December 1773 as a protest against British tax laws . The harsh British response to this act in 1774 , which included sending British troops to Boston and closing Boston Harbor , caused tensions and resentments to escalate further . The British tried to disarm the insurgents in Massachusetts by their weapons and ammunition and arresting the leaders of the patriotic movement . However , this effort faltered on April 19 , when Massachusetts militias and British troops on each other as British troops marched to Lexington and Concord , an event immortalized by poet Ralph Waldo Emerson as the shot heard round the world . The American Revolution had begun . ON THE EVE OF REVOLUTION The decade from 1763 to 1774 was a one for the British Empire . Although Great Britain had defeated the French in the French and Indian War , the debt from that conflict remained a stubborn and seemingly unsolvable problem for both Great Britain and the colonies . Great Britain tried various methods of raising revenue on both sides of the Atlantic to manage the enormous debt , including instituting a tax on tea and other goods sold to the colonies by British companies , but many subjects resisted these taxes . In the colonies , Patriot groups like the Sons of Liberty led boycotts of British goods and took violent measures that stymied British . Boston proved to be the epicenter . In December 1773 , a group of Patriots protested the Tea Act passed that , among other provisions , gave the East India Company a monopoly on boarding British tea ships docked in Boston Harbor and dumping tea worth over million ( in current prices ) Access for free at .

Britain Strategy and Its Consequences 141 into the water . The destruction of the tea radically escalated the crisis between Great Britain and the American colonies . When the Massachusetts Assembly refused to pay for the tea , Parliament enacted a series of laws called the Coercive Acts , which some colonists called the Intolerable Acts . Parliament designed these laws , which closed the port of Boston , limited the meetings of the colonial assembly , and disbanded all town meetings , to punish Massachusetts and bring the colony into line . However , many British Americans in other colonies were troubled and angered by Parliament response to Massachusetts . In September and October 1774 , all the colonies except Georgia participated in the First Continental Congress in Philadelphia . The Congress advocated a boycott of all British goods and established the Continental Association to enforce local adherence to the boycott . The Association supplanted royal control and shaped resistance to Great Britain . AMERICANA Joining the Boycott Many British colonists in Virginia , as in the other colonies , disapproved ofthe destruction of the tea in Boston Harbor . However , after the passage of the Coercive Acts , the Virginia House of Burgesses declared its solidarity with Massachusetts by encouraging Virginians to observe a day of fasting and prayer on May sympathy with the people of Boston . Almost immediately thereafter , Virginia colonial governor dissolved the House of Burgesses , but many of its members met again in secret on May 30 and adopted a resolution the Colony of Virginia will concur with the other Colonies in such Measures as shall be judged most effectual forthe preservation of the Common Rights and Liberty of British America . After the First Continental Congress in Philadelphia , Virginia Committee of Safety ensured that all merchants signed the agreements that the Congress had proposed . This British cartoon Figure shows a Virginian signing the Continental Association boycott agreement . FIGURE In The Alternative of ( 1775 ) a merchant has to sign a agreement or risk being covered with the tar and feathers suspended behind him . Note the tar and feathers the gallows in the background of this image and the demeanor of the people surrounding the signer . What is the message of this engraving ?

Where are the sympathies of the artist ?

What is the meaning of the title The Alternative of ?

In an effort to restore law and order in Boston , the British dispatched General Thomas Gage to the New England seaport . He arrived in Boston in May 1774 as the new royal governor of the Province of Massachusetts , accompanied by several regiments of British troops . As in 1768 , the British again occupied the town .

142 America War for Independence , Massachusetts delegates met in a Provincial Congress and published the Suffolk Resolves , which rejected the Coercive Acts and called for the raising of colonial militias to take military action if needed . The Suffolk Resolves signaled the overthrow of the royal government in Massachusetts . Both the British and the rebels in New England began to prepare for by turning their attention to supplies of weapons and gunpowder . General Gage stationed hundred troops in Boston , and from there he ordered periodic raids on towns where guns and gunpowder were stockpiled , hoping to impose law and order by seizing them . As Boston became the headquarters of British military operations , many residents the city . Gage actions led to the formation of local rebel militias that were able to mobilize in a minute time . These minutemen , many of whom were veterans of the French and Indian War , played an important role in the war for independence . In one instance , General Gage seized munitions in Cambridge and Charlestown , but when he arrived to do the same in Salem , his troops were met by a large crowd of minutemen and had to leave . In New Hampshire , minutemen took over Fort William and Mary and weapons and cannons there . New England readied for war . THE OUTBREAK OF FIGHTING Throughout late 1774 and into 1775 , tensions in New England continued to mount . General Gage knew that a powder magazine was stored in Concord , Massachusetts , and on April 19 , 1775 , he ordered troops to seize these munitions . Instructions from London called for the arrest of rebel leaders Samuel Adams and John Hancock . Hoping for secrecy , his troops left Boston under cover of darkness , but riders from Boston let the militias know of the British plans . Paul Revere was one of these riders , but the British captured him and he never his ride . Henry Wadsworth Longfellow memorialized Revere in his 1860 poem , Paul Revere Ride , incorrectly implying that he made it all the way to Concord . Minutemen met the British troops and skirmished with them , at Lexington and then at Concord ( Figure . The British retreated to Boston , enduring ambushes from several other militias along the way . Over four thousand militiamen took part in these skirmishes with British soldiers . British soldiers and Patriots died during the British retreat to Boston . The famous confrontation is the basis for Emerson Concord Hymn ( 1836 ) which begins with the description of the shot heard round the world . Although propagandists on both sides pointed , it remains unclear who that shot . FIGURE Amos Doolittle was an American who volunteered to against the British . His engravings of the battles of Lexington and as this detail from The Battle , April the only contemporary American visual records of the events there . After the battles of Lexington and Concord , New England fully mobilized for war . Thousands of militias from towns throughout New England marched to Boston , and soon the city was besieged by a sea of rebel forces Figure ) In May 1775 , Ethan Allen and Colonel Benedict Arnold led a group of rebels against Fort in New York . They succeeded in capturing the fort , and cannons from were brought Access for free at .

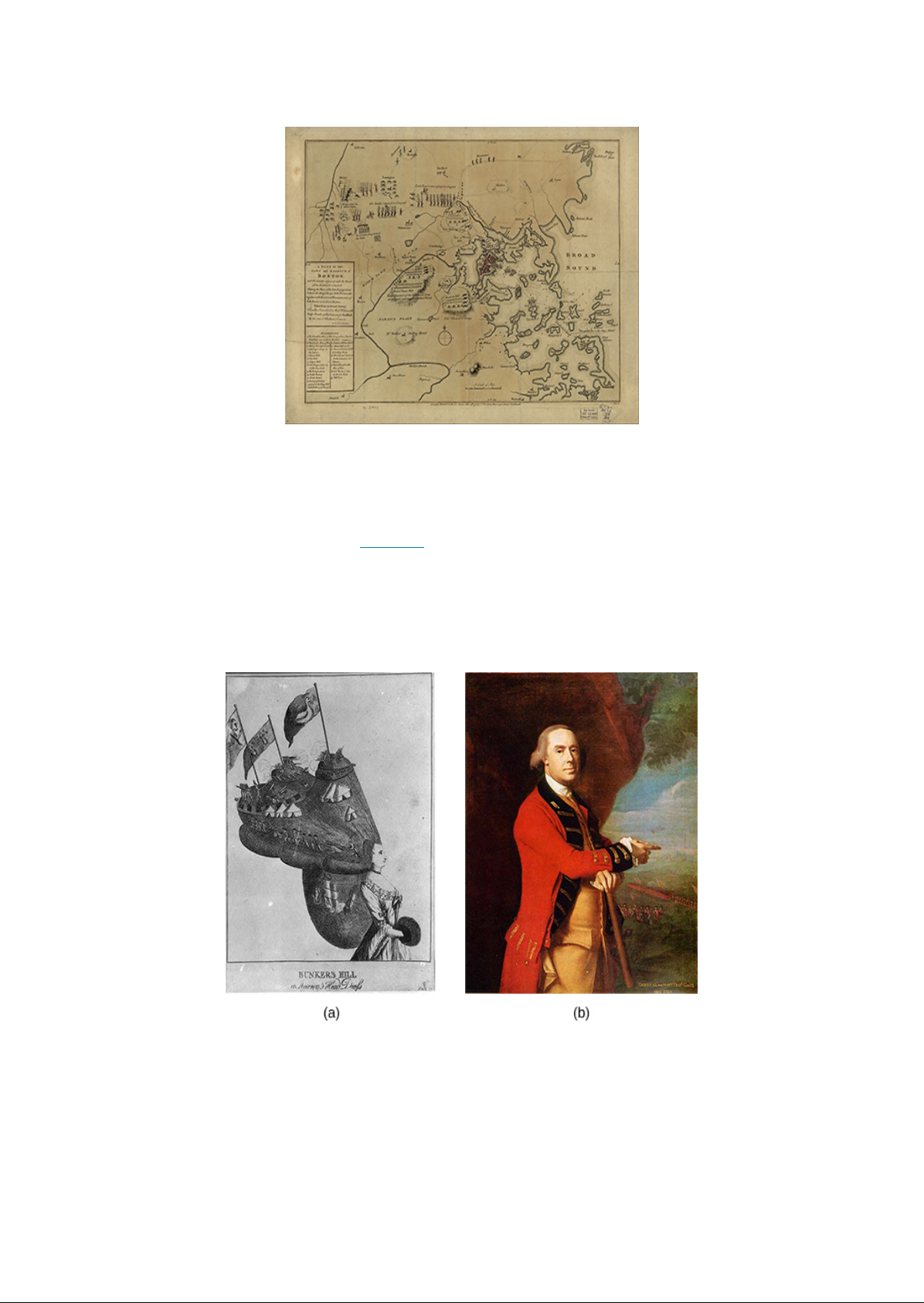

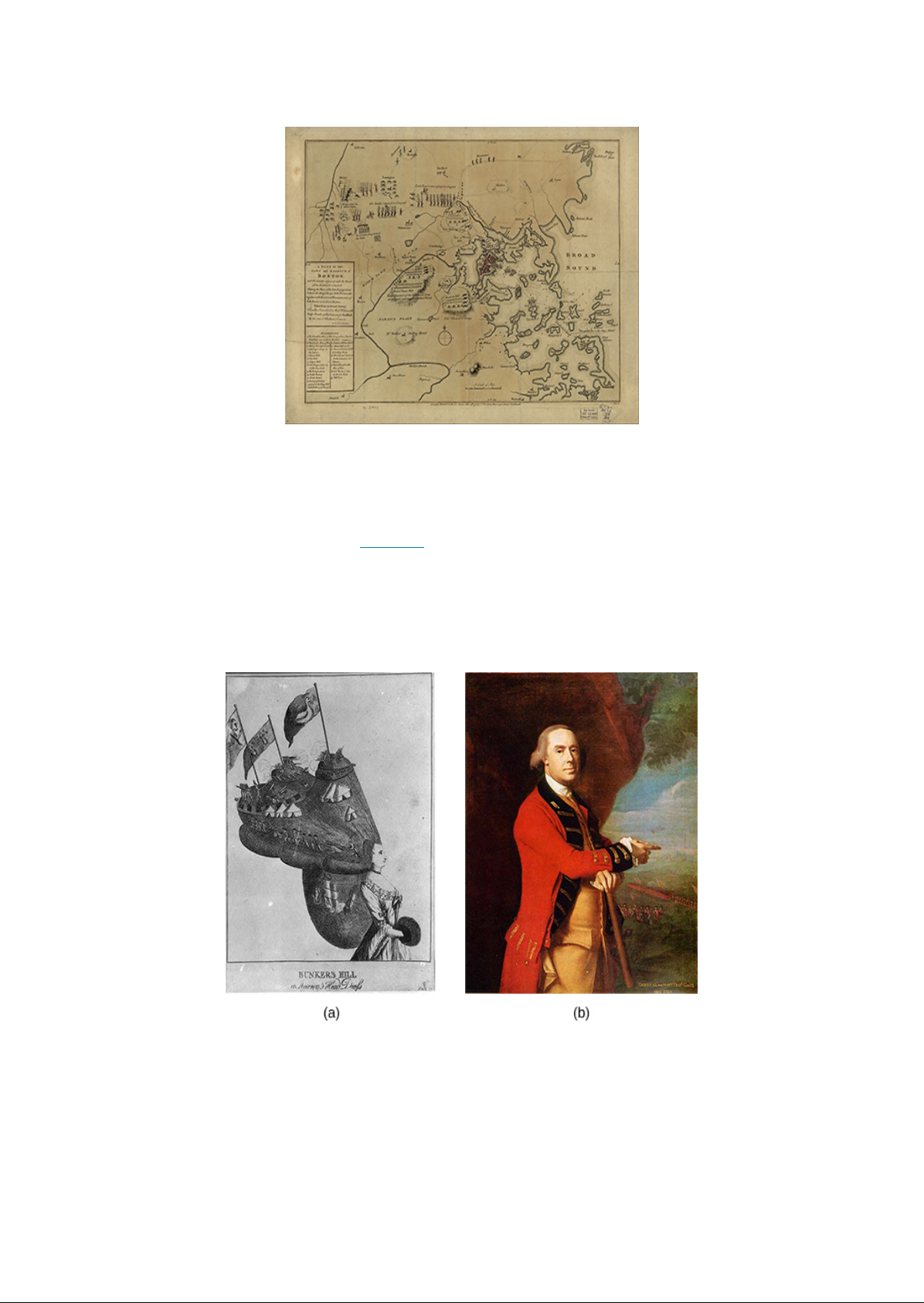

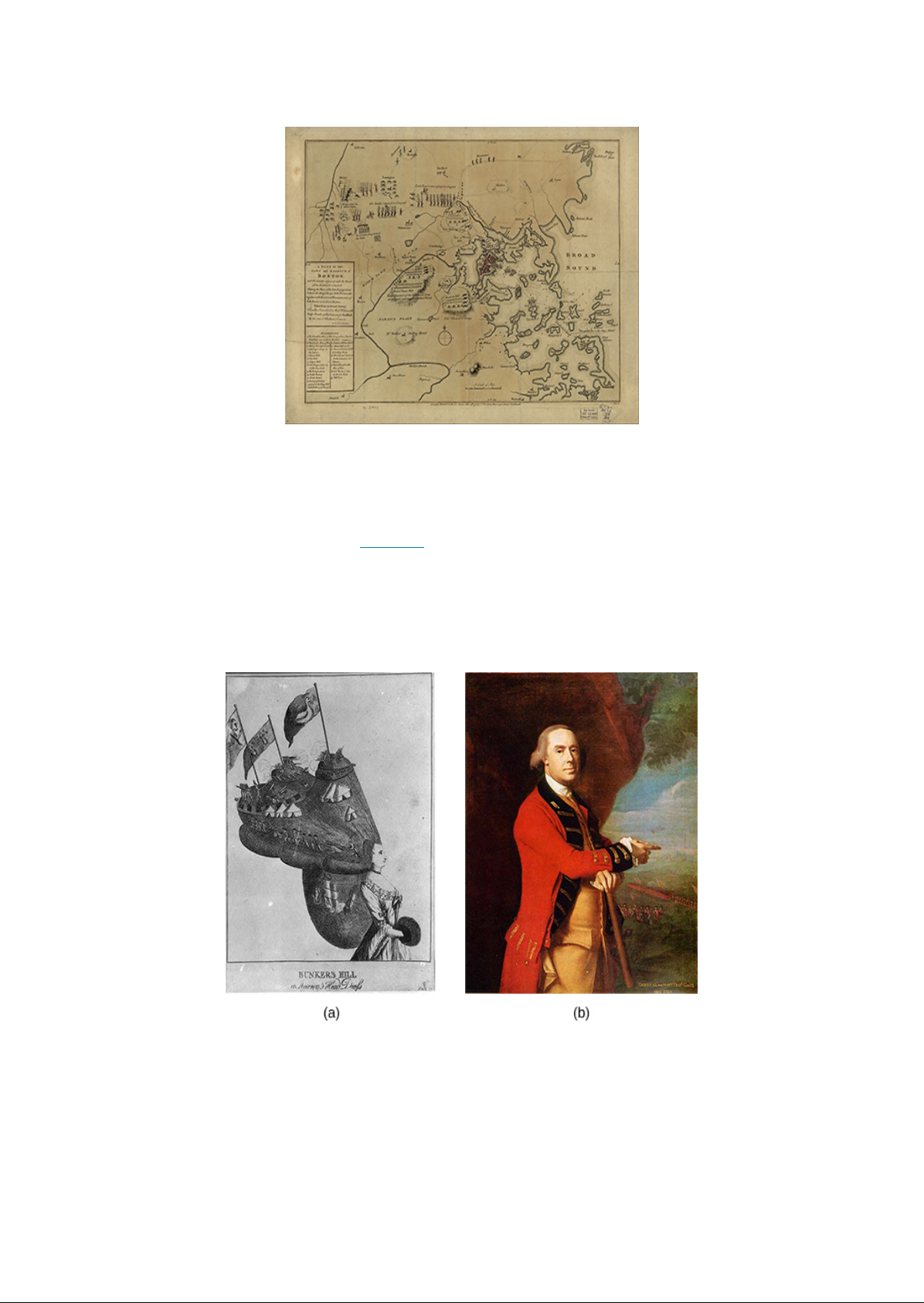

Britain Strategy and Its Consequences 143 to Massachusetts and used to bolster the Siege of Boston . ea FIGURE This 1779 map shows details of the British and Patriot troops in and around Boston , Massachusetts , at the beginning of the war . In June , General Gage resolved to take Breed Hill and Bunker Hill , the high ground across the Charles River from Boston , a strategic site that gave the rebel militias an advantage since they could train their cannons on the British . In the Battle of Bunker Hill Figure , on June 17 , the British launched three assaults on the hills , gaining control only after the rebels ran out of ammunition . British losses were very two hundred were killed and eight hundred , despite his victory , General Gage was unable to break the colonial forces siege of the city . In August , King George III declared the colonies to be in a state of rebellion . Parliament and many in Great Britain agreed with their king . Meanwhile , the British forces in Boston found themselves in a terrible predicament , isolated in the city and with no control over the countryside . FIGURE The British cartoon Bunkers Hill or America Head Dress ( a ) depicts the initial rebellion as an elaborate colonial coiffure . The illustration pokes fun at both the colonial rebellion and the overdone hairstyles for women that had made their way from France and Britain to the American colonies . Despite gaining control ofthe high ground after the colonial militias ran out of ammunition , General Thomas Gage ( shown here in a painting made in by John Singleton Copley , was unable to break the siege of the city . In the end , General George Washington , commander in chief of the Continental Army since June 15 , 1775 , used the Fort cannons to force the evacuation of the British from Boston . Washington had

144 America War for Independence , positioned these cannons on the hills overlooking both the positions of the British and Boston Harbor , where the British supply ships were anchored . The British could not return on the colonial positions because they could not elevate their cannons . They soon realized that they were in an untenable position and had to withdraw from Boston . On March 17 , 1776 , the British evacuated their troops to Halifax , Nova Scotia , ending the nearly siege . By the time the British withdrew from Boston , had broken out in other colonies as well . In May 1775 , County in North Carolina issued the Resolves , stating that a rebellion against Great Britain had begun , that colonists did not owe any further allegiance to Great Britain , and that governing authority had now passed to the Continental Congress . The resolves also called upon the formation of militias to be under the control of the Continental Congress . Loyalists and Patriots clashed in North Carolina in February 1776 at the Battle of Moore Creek Bridge . In Virginia , the royal governor , Lord Dunmore , raised Loyalist forces to combat the rebel colonists and also tried to use the large enslaved population to put down the rebellion . In November 1775 , he issued a decree , known as Dunmore Proclamation , promising freedom to enslaved people and indentured servants of rebels who remained loyal to the king and who pledged to with the Loyalists against the insurgents . Dunmore Proclamation exposed serious problems for both the Patriot cause and for the British . In order for the British to put down the rebellion , they needed the support of Virginia landowners , many of whom enslaved people . While Patriot slaveholders in Virginia and elsewhere proclaimed they acted in defense of liberty , they kept thousands in bondage , a fact the British decided to exploit . Although a number of enslaved people did join Dunmore side , the proclamation had the unintended effect of galvanizing Patriot resistance to Britain . From the rebels point of view , the British looked to deprive them of their enslaved property and incite a race war . Slaveholders feared an uprising and increased their commitment to the cause against Great Britain , calling for independence . Dunmore Virginia in 1776 . COMMON SENSE With the events of 1775 fresh in their minds , many colonists reached the conclusion in 1776 that the time had come to secede from the Empire and declare independence . Over the past ten years , these colonists had argued that they deserved the same rights as Englishmen enjoyed in Great Britain , only to themselves relegated to an intolerable subservient status in the Empire . The groundswell of support for their cause of independence in 1776 also owed much to the appearance of an anonymous pamphlet , published in January 1776 , entitled Common Sense . Thomas Paine , who had emigrated from England to Philadelphia in 1774 , was the author . Arguably the most radical pamphlet of the revolutionary era , Common Sense made a powerful argument for independence . Paine pamphlet rejected the monarchy , calling King George III a royal brute and questioning the right of an island ( England ) to rule over America . In this way , Paine helped to channel colonial discontent toward the king himself and not , as had been the case , toward the British bold move that signaled the desire to create a new political order disavowing monarchy entirely . He argued for the creation of an American republic , a state without a king , and extolled the blessings of republicanism , a political philosophy that held that elected representatives , not a hereditary monarch , should govern states . The vision of an American republic put forward by Paine included the idea of popular sovereignty citizens in the republic would determine who would represent them , and decide other issues , on the basis of majority rule . Republicanism also served as a social philosophy guiding the conduct of the Patriots in their struggle against the British Empire . It demanded adherence to a code of virtue , placing the public good and community above narrow . Paine wrote Common Sense Figure ) in simple , direct language aimed at ordinary people , not just the learned elite . The pamphlet proved immensely popular and was soon available in all thirteen colonies , where it helped convince many to reject monarchy and the British Empire in favor of independence and a republican form of government . Access for free at .

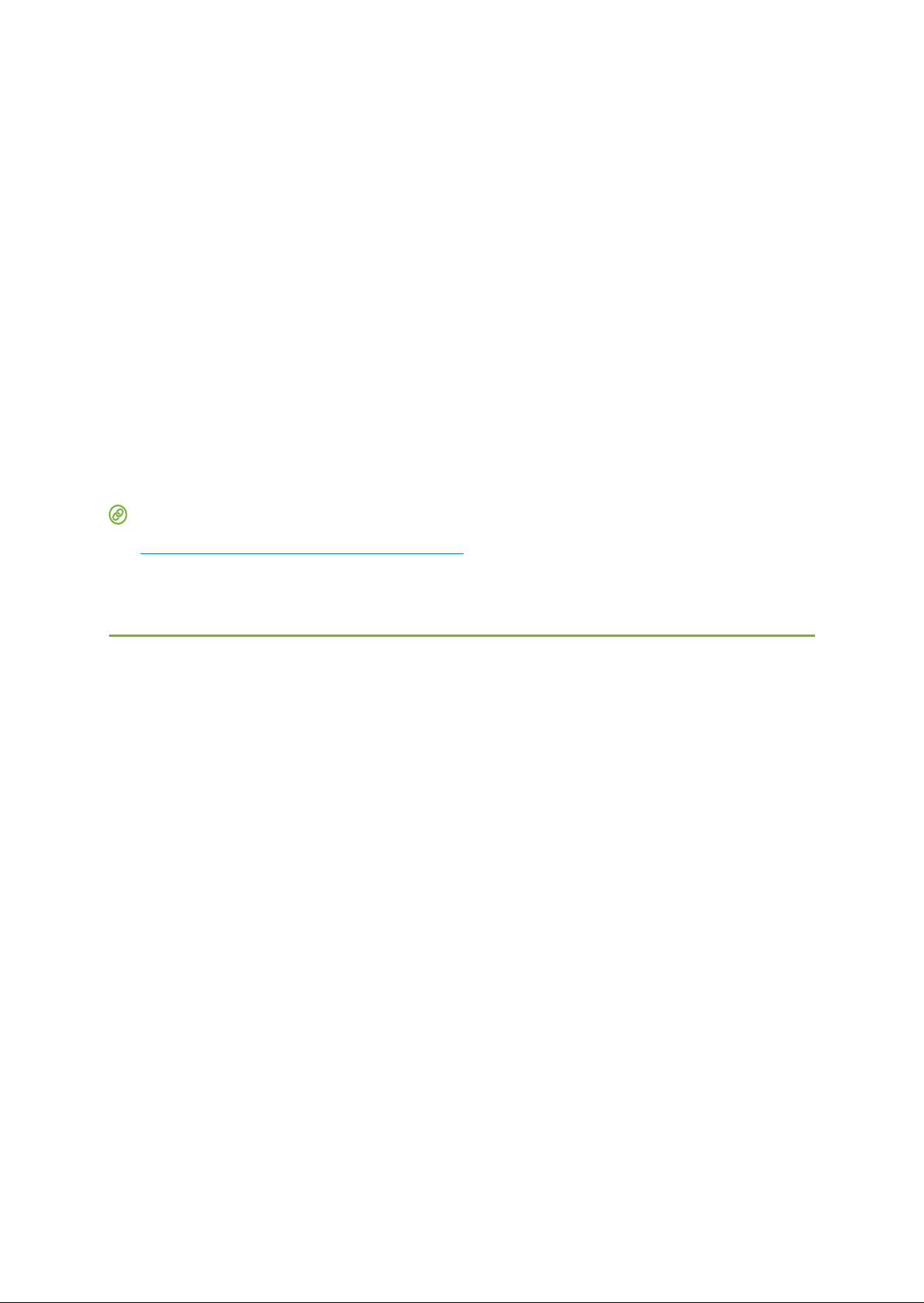

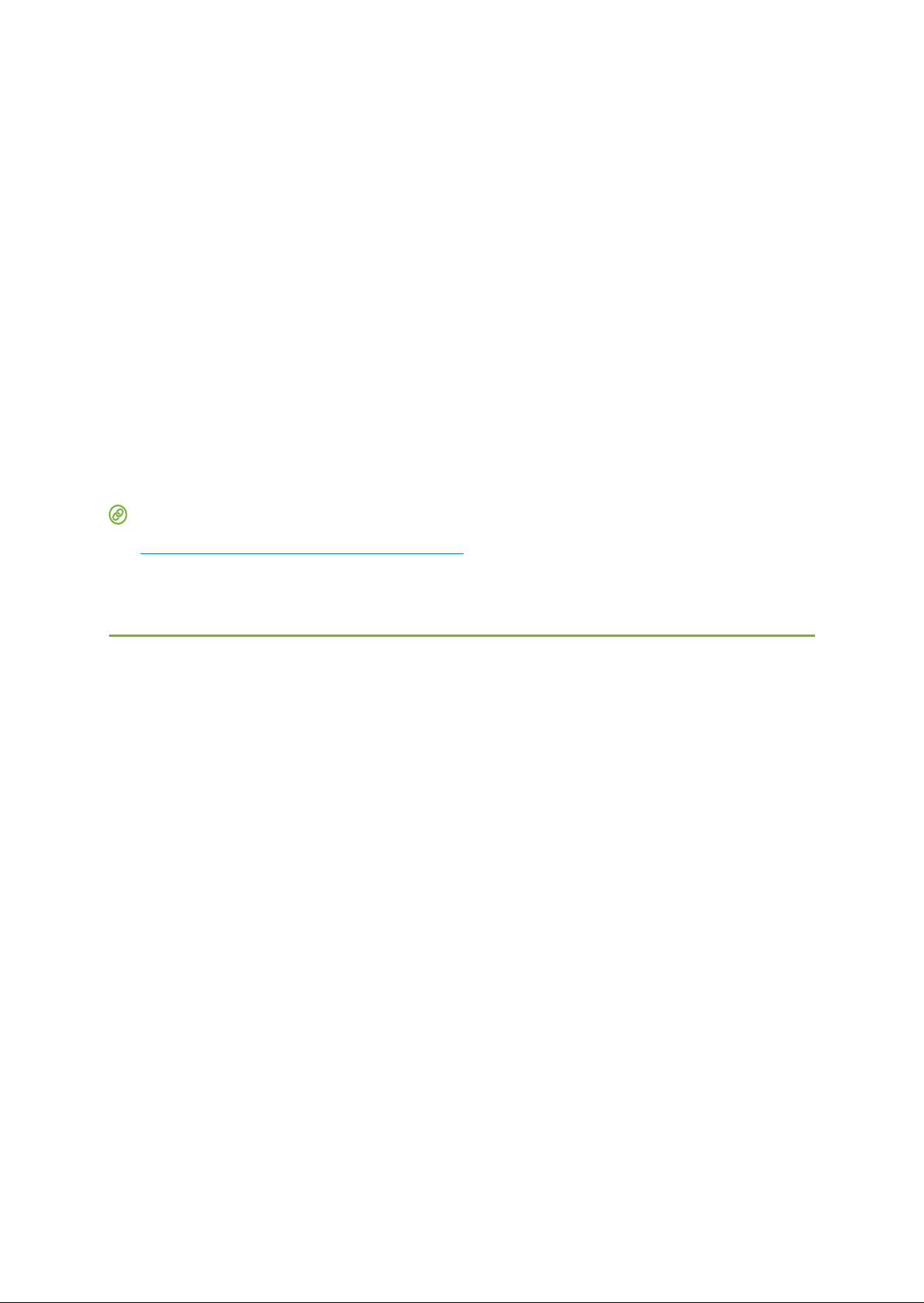

Britain Strategy and Its Consequences 145 . AMERICA , FIGURE Thomas Paine Common Sense ( a ) helped convince many colonists of the need for independence from Great Britain . Paine , shown here in a portrait by Laurent ( was a political activist and revolutionary best known for his writings on both the American and French Revolutions . THE DECLARATION OF INDEPENDENCE In the summer of 1776 , the Continental Congress met in Philadelphia and agreed to sever ties with Great Britain . Virginian Thomas Jefferson and John Adams of Massachusetts , with the support of the Congress , articulated the justification for liberty in the Declaration of Independence Figure . The Declaration , written primarily by Jefferson , included a long list of grievances against King George III and laid out the foundation of American government as a republic in which the consent of the governed would be of paramount importance . um I ) I . I I . A ( FIGURE The Broadsides , one of which is shown here , are considered the published copies ofthe Declaration of Independence . This one was printed on July . The preamble to the Declaration began with a statement of Enlightenment principles about universal human rights and values We hold these Truths to be , that all Men are created equal , that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights , that among these are Life , Liberty , and the pursuit of to secure these Rights , Governments are instituted among Men , deriving their just Powers

146 America War for Independence , from the Consent of the Governed , that it is the Right of the People to alter or abo served another purpose Patriot leaders aid in the contest against Great Britain . to the creation of a new and independent any Form of Government becomes destructive of these Ends , ish it . In addition to this statement of principles , the document ent copies to France and Spain in hopes their support and understood how important foreign recognition and aid would be nation . The Declaration of Independence has since had a global impact , serving as the basis for many subsequent movements to gain independence from her colonial powers . It is part of America civil religion , and thousands of people each year make pilgrimages to see the original document in Washington , The Declaration also reveals a existence of slavery and the idea that all al contradiction of the American Revolution the between the men are created equal . of the population in 1776 was enslaved , and at the time he drafted the Declaration , Jefferson himself owned more than one hundred enslaved individuals . Further , the Declaration framed equality as existing only among White men women and people were entirely left out a document that referred to Native peoples as merciless Indian savages who indiscriminately killed men , women , and children . Nonetheless , the promise of equality for all planted the seeds for future struggles waged by enslaved individuals , women , and many others to bring about its full realization . Much of American his ory is the story of the slow realization of the promise of equality expressed in the Declaration of ence . CLICK AND EXPLORE Visit Digital History ( to view The Female Combatants . In this 1776 engraving by an anonymous artist , Great Britain is depicted on the left as a staid , stern matron , while America , on the right , is shown as a Native American . Why do you think the artist depicted the two opposing sides this way ?

The Early Years of the Revolution LEARNING OBJECTIVES By the end ofthis section , you will be able to Explain the British and American strategies of 1776 through 1778 Identify the key battles of the early years of the Revolution After the British quit Boston , they slowly adopted a strategy to isolate New England from the rest of the colonies and force the insurgents in that region into submission , believing that doing so would end the . At , British forces focused on taking the principal colonial centers . They began by easily capturing New York City in 1776 . The following year , they took over the American capital of Philadelphia . The larger British effort to isolate New England was implemented in 1777 . That effort ultimately failed when the British surrendered a force of over five thousand to the Americans in the fall of 1777 at the Battle of Saratoga . The major campaigns over the next several years took place in the middle colonies of New York , New Jersey , and Pennsylvania , whose populations were sharply divided between Loyalists and Patriots . Revolutionaries faced many hardships as British superiority on the became evident and the of funding the war caused strains . THE BRITISH STRATEGY IN THE MIDDLE COLONIES After evacuating Boston in March 1776 , British forces sailed to Nova Scotia to regroup . They devised a strategy , successfully implemented in 1776 , to take New York City . The following year , they planned to end the rebellion by cutting New England off from the rest of the colonies and starving it into submission . Three British armies were to move simultaneously from New York City , Montreal , and Fort to converge along the Hudson River British control of that natural boundary would isolate New England . Access for free at .

The Early Years of the Revolution General William Howe ( Figure , commander in chief of the British forces in America , amassed thousand troops on Staten Island in June and July 1776 . His brother , Admiral Richard Howe , controlled New York Harbor . Command of New York City and the Hudson River was their goal . In August 1776 , General Howe landed his forces on Long Island and easily routed the American Continental Army there in the Battle of Long Island ( August 27 ) The Americans were outnumbered and lacked both military experience and discipline . Sensing victory , General and Admiral Howe arranged a peace conference in September 1776 , where Benjamin Franklin , John Adams , and South John Rutledge represented the Continental Congress . Despite the hopes , however , the Americans demanded recognition of their independence , which the were not authorized to grant , and the conference disbanded . FIGURE General William Howe , shown here in a 1777 portrait by Richard Purcell , led British forces in America in the first years of the war . On September 16 , 1776 , George Washington forces held up against the British at the Battle of Harlem Heights . This important American military achievement , a key reversal after the disaster on Long Island , occurred as most of Washington forces retreated to New Jersey . A few weeks later , on October 28 , General Howe forces defeated Washington at the Battle of White Plains and New York City fell to the British . For the next seven years , the British made the city the headquarters for their military efforts to defeat the rebellion , which included raids on surrounding areas . In 1777 , the British burned Danbury , Connecticut , and in July 1779 , they set to homes in and . They held American prisoners aboard ships in the waters around New York City the death toll was shocking , with thousands perishing in the holds . Meanwhile , New York City served as a haven for Loyalists who disagreed with the effort to break away from the Empire and establish an American republic . GEORGE WASHINGTON AND THE CONTINENTAL ARMY When the Second Continental Congress met in Philadelphia in May 1775 , members approved the creation of a professional Continental Army with Washington as commander in chief Figure . Although sixteen thousand volunteers enlisted , it took several years for the Continental Army to become a truly professional force . In 1775 and 1776 , militias still composed the bulk of the Patriots armed forces , and these soldiers returned home after the summer season , drastically reducing the army strength .

148 America War for Independence , FIGURE This 1775 etching shows George Washington taking command of the Continental Army at Cambridge , Massachusetts , just two weeks after his appointment by the Continental Congress . That changed in late 1776 and early 1777 , when Washington broke with conventional military tactics that called for in the summer months only . Intent on raising revolutionary morale after the British captured New York City , he launched surprise strikes against British forces in their winter quarters . In Trenton , New Jersey , he led his soldiers across the Delaware River and surprised an encampment of Hessians , German mercenaries hired by Great Britain to put down the American rebellion . Beginning the night of December 25 , 1776 , and continuing into the early hours of December 26 , Washington moved on Trenton where the Hessians were encamped . Maintaining the element of surprise by attacking at Christmastime , he defeated them , taking over nine hundred captive . On January , 1777 , Washington achieved another victory at the Battle of Princeton . He again broke with military protocol by attacking unexpectedly after the season had ended . DEFINING AMERICAN Thomas Paine on The American Crisis During the American Revolution , following the publication of Common Sense in January 1776 , Thomas Paine began a series of sixteen pamphlets known collectively as The American Crisis Figure 611 ) He wrote the first volume in 1776 , describing the dire situation facing the revolutionaries at the end of that hard year . Access for free at .

The Early Years of the Revolution . The A . mu Um I A . FIGURE Thomas Paine wrote the pamphlet The American Crisis , the first page of which is shown here , in 1776 . These are the times that try men souls . The summer soldier and the sunshine patriot will , in this crisis , shrink from the service of their country but we that stands it now , deserves the love and thanks of man and woman . Britain , with an army to enforce , has declared that she has a right ( not only to tax ) but to bind us in all cases whatsoever , and if being bound in that manner , is not slavery , then is there not such a thing as slavery upon earth . Even the expression is im for so unlimited a power can belong only to God . I shall conclude this paper with some miscellaneous remarks on the state of our affairs and shall begin with following question , Why is it that the enemy have left the New England provinces , and made these middle ones the seat of war ?

The answer is easy New England is not infested with Tories , and we are . I have been tender in raising the cry against hese men , and used numberless arguments to show them their danger , but it will not do to a world either to their folly or their baseness . The period is now arrived , in which either they or we must change our , or one or both must fall . By perseverance and fortitude we have the prospect of a glorious issue by cowardice and submission , the sad choice of a variety of ravaged depopulated without safety , and slavery without homes turned into and for Hessians , and a future race to provide for , whose fathers we shall doubt of . Look on this picture and weep over it ! and ifthere yet remains one thoughtless wretch who believes it not , let him er it unlamented . Paine , The American Crisis , December What topics does Paine address in this pamphlet ?

What was his purpose in writing ?

What does he write about Tories ( Loyalists ) and why does he consider them a problem ?

CLICK AND EXPLORE Visit to read the rest Paine American Crisis pamphlet , as well as the other in the series . 149 150 America War for Independence , PHILADELPHIA AND SARATOGA BRITISH AND AMERICAN VICTORIES In August 1777 , General Howe brought thousand British troops to Chesapeake Bay as part of his plan to take Philadelphia , where the Continental Congress met . That fall , the British defeated Washington soldiers in the Battle of Brandywine Creek and took control of Philadelphia , forcing the Continental Congress to . During the winter of , the British occupied the city , and Washington army camped at Valley Forge , Pennsylvania . Washington winter at Valley Forge was a low point for the American forces . A lack of supplies weakened the men , and disease took a heavy toll . Amid the cold , hunger , and sickness , soldiers deserted in droves . On February 16 , Washington wrote to George Clinton , governor of New York For some days past , there has been little less than a famine in camp . A part of the army has been a week without any kind of the rest three or four days . Naked and starving as they are , we can not enough admire the incomparable patience and of the soldiery , that they have not been ere before this excited by their sufferings to a general mutiny and dispersion . Of eleven thousand soldiers encamped at Valley Forge , hundred died of starvation , malnutrition , and disease . As Washington feared , nearly one hundred soldiers deserted every week . Desertions continued , and by 1780 , Washington was executing recaptured deserters every Saturday . The low morale extended all the way to Congress , where some wanted to replace Washington with a more seasoned leader . Assistance came to Washington and his soldiers in February 1778 in the form of the Prussian soldier Friedrich Wilhelm von Figure . Baron von was an experienced military man , and he implemented a thorough training course for Washington ragtag troops . By drilling a small corps of soldiers and then having them train others , he transformed the Continental Army into a force capable of standing up to the professional British and Hessian soldiers . His drill for the Order and Discipline of the Troops of the United military practices in the United States for the next several decades . FIGURE Prussian soldier Friedrich Wilhelm von , shown here in a 1786 portrait by Ralph Earl , was instrumental in transforming Washington Continental Army into a professional armed force . CLICK AND EXPLORE Explore Friedrich Wilhelm von Revolutionary War Drill Manual ( to understand how von was able to transform the Continental Army into a professional force . Note the tremendous amount of precision and detail in von descriptions . Meanwhile , the campaign to sever New England from the rest of the colonies had taken an unexpected turn during the fall of 1777 . The British had attempted to implement the plan , drawn up by Lord George Germain Access for free at .

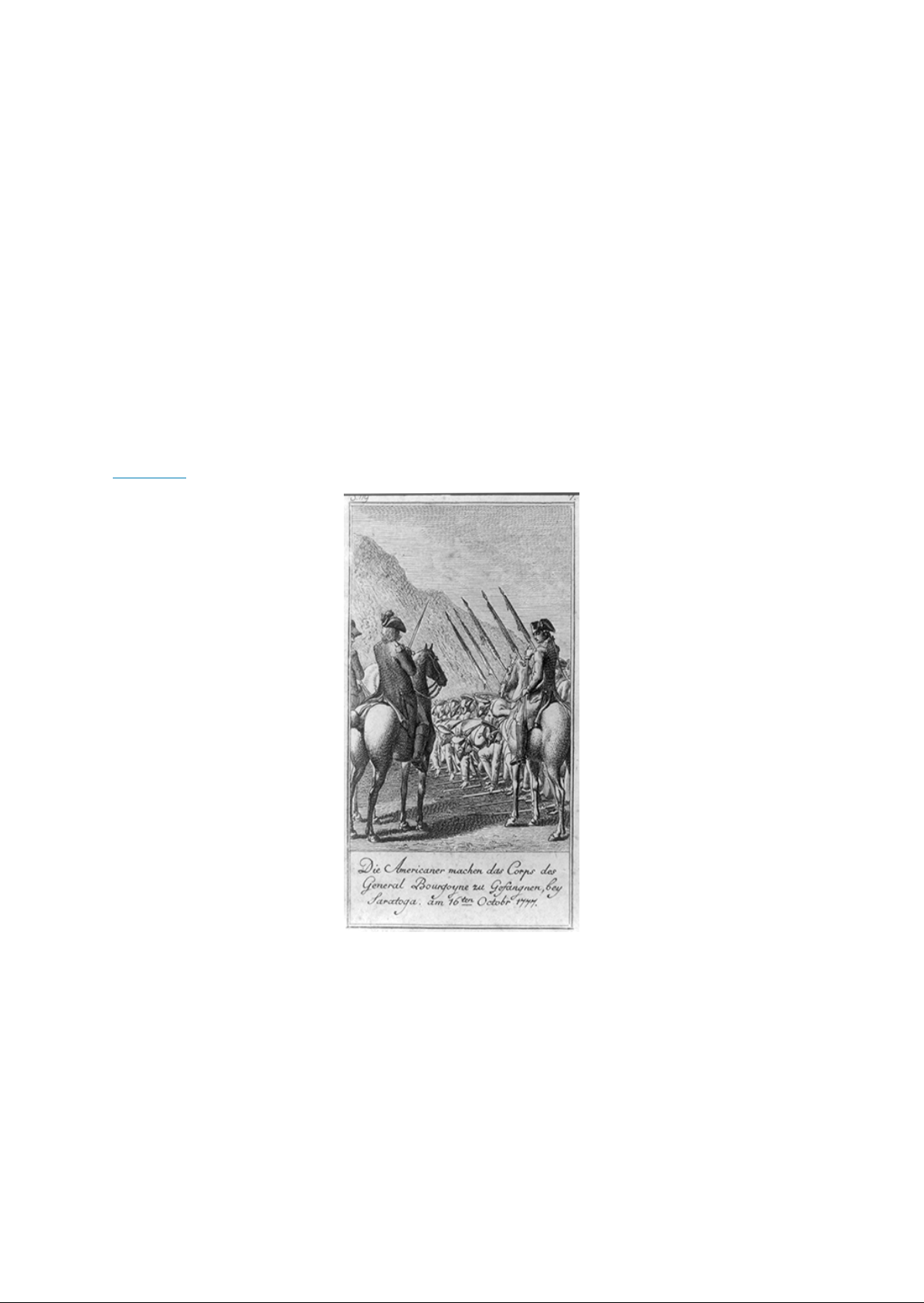

The Early Years of the Revolution 151 and Prime Minister Lord North , to isolate New England with the combined forces of three armies . One army , led by General John Burgoyne , would march south from Montreal . A second force , led by Colonel Barry Leger and made up of British troops and Iroquois , would march east from Fort on the banks of Lake Ontario . A third force , led by General Sir Henry Clinton , would march north from New York City . The armies would converge at Albany and effectively cut the rebellion in two by isolating New England . This northern campaign fell victim to competing strategies , however , as General Howe had meanwhile decided to take Philadelphia . His decision to capture that city siphoned off troops that would have been vital to the overall success of the campaign in 1777 . The British plan to isolate New England ended in disaster . Leger efforts to bring his force of British regulars , Loyalist , and Iroquois allies east to link up with General Burgoyne failed , and he retreated to Quebec . Burgoyne forces encountered resistance as he made his way south from Montreal , down Lake and the upper Hudson River corridor . Although they did capture Fort when American forces retreated , Burgoyne army found themselves surrounded by a sea of colonial militias in Saratoga , New York . In the meantime , the small British force under Clinton that left New York City to aid Burgoyne advanced slowly up the Hudson River , failing to provide the support for the troops at Saratoga . On October 17 , 1777 , Burgoyne surrendered his thousand soldiers to the Continental Army Figure . IA , FIGURE This German engraving , created by Daniel in 1784 , shows British soldiers laying down their arms before the American forces . The American victory at the Battle of Saratoga was the major turning point in the war . This victory convinced the French to recognize American independence and form a military alliance with the new nation , which changed the course of the war by opening the door to badly needed military support from France . Still smarting from their defeat by Britain in the Seven Years War , the French supplied the United States with gunpowder and money , as well as soldiers and naval forces that proved decisive in the defeat of Great Britain . The French also contributed military leaders , including the Marquis de Lafayette , who arrived in America in 1777 as a volunteer and served as Washington . The war quickly became more for the British , who had to the rebels in North America as well as the French in the Caribbean . Following France lead , Spain joined the war against Great Britain in 1779 ,

152 America War for Independence , though it did not recognize American independence until 1783 . The Dutch Republic also began to support the American revolutionaries and signed a treaty of commerce with the United States in 1782 . Great Britain effort to isolate New England in 1777 failed . In June 1778 , the occupying British force in Philadelphia evacuated and returned to New York City in order to better defend that city , and the British then turned their attention to the southern colonies . War in the South LEARNING OBJECTIVES By the end ofthis section , you will be able to Outline the British southern strategy and its results Describe key American victories and the end of the war Identify the main terms of the Treaty of Paris ( 1783 ) By 1778 , the war had turned into a stalemate . Although some in Britain , including Prime Minister Lord North , wanted peace , King George III demanded that the colonies be brought to obedience . To break the deadlock , the British revised their strategy and turned their attention to the southern colonies , where they could expect more support from Loyalists . The southern colonies soon became the center of the . The southern strategy brought the British success at first , but thanks to the leadership of George Washington and General Greene and the crucial assistance of French forces , the Continental Army defeated the British at Yorktown , effectively ending further operations during the war . GEORGIA AND SOUTH CAROLINA The British architect of the war strategy , Lord George Germain , believed Britain would gain the upper hand with the support of Loyalists , enslaved people , and Native American allies in the South , and indeed , this southern strategy initially achieved great success . The British began their southern campaign by capturing Savannah , the capital of Georgia , in December 1778 . In Georgia , they found support from thousands of enslaved individuals who ran to the British side to escape their bondage . As the British regained political control in Georgia , they forced the inhabitants to swear allegiance to the king and formed twenty Loyalist regiments . The Continental Congress had suggested that enslaved people be given freedom if the Patriot army against the British , but revolutionaries in Georgia and South Carolina refused to consider this proposal . Once again , the Revolution served to further divisions over race and slavery . After taking Georgia , the British turned their attention to South Carolina . Before the Revolution , South Carolina had been starkly divided between the backcountry , which harbored revolutionary partisans , and the coastal regions , where Loyalists remained a powerful force . Waves of violence rocked the backcountry from the late into the early . The Revolution provided an opportunity for residents to over their local resentments and with murderous consequences . Revenge killings and the destruction of property became in the savage civil war that gripped the South . In April 1780 , a British force of eight thousand soldiers besieged American forces in Charleston ( Figure . After six weeks of the Siege of Charleston , the British triumphed . General Benjamin Lincoln , who led the effort for the revolutionaries , had to surrender his entire force , the largest American loss during the entire war . Many of the defeated Americans were placed in jails or in British prison ships anchored in Charleston Harbor . The British established a military government in Charleston under the command of General Sir Henry Clinton . From this base , Clinton ordered General Charles Cornwallis to subdue the rest of South Carolina . Access for free at .

War in the South 153 FIGURE This 1780 map of Charleston ( a ) which shows details of the Continental defenses , was probably drawn by British engineers in anticipation of the attack on the city . The Siege of Charleston was one of a series of defeats for the Continental forces in the South , which led the Continental Congress to place General Greene ( shown here in a 1783 portrait by Charles Wilson , in command in late 1780 . Greene led his troops to two crucial victories . The disaster at Charleston led the Continental Congress to change leadership by placing General Horatio Gates in charge of American forces in the South . However , General Gates fared no better than General Lincoln at the Battle of Camden , South Carolina , in August 1780 , Cornwallis forced General Gates to retreat into North Carolina . Camden was one of the worst disasters suffered by American armies during the entire Revolutionary War . Congress again changed military leadership , this time by placing General Greene Figure in command in December 1780 . As the British had hoped , large numbers of Loyalists helped ensure the success of the southern strategy , and thousands of enslaved individuals seeking freedom arrived to aid Cornwallis army . However , the war turned in the Americans favor in 1781 . General Greene realized that to defeat Cornwallis , he did not have to win a single battle . So long as he remained in the , he could continue to destroy isolated British forces . Greene therefore made a strategic decision to divide his own troops to wage the strategy worked . American forces under General Daniel Morgan decisively beat the British at the Battle of in South Carolina . General Cornwallis now abandoned his strategy of defeating the backcountry rebels in South Carolina . Determined to destroy Greene army , he gave chase as Greene strategically retreated north into North Carolina . At the Battle of Courthouse in March 1781 , the British prevailed on the but suffered extensive losses , an outcome that paralleled the Battle of Bunker Hill nearly six years earlier in June 1775 . YORKTOWN In the summer of 1781 , Cornwallis moved his army to Yorktown , Virginia . He expected the Royal Navy to transport his army to New York , where he thought he would join General Sir Henry Clinton . Yorktown was a tobacco port on a peninsula , and Cornwallis believed the British navy would be able to keep the coast clear of rebel ships . Sensing an opportunity , a combined French and American force of sixteen thousand men swarmed the peninsula in September 1781 . Washington raced south with his forces , now a disciplined army , as did the Marquis de Lafayette and the Comte de Rochambeau with their French troops . The French Admiral de sailed his naval force into Chesapeake Bay , preventing Lord Cornwallis from taking a seaward escape route . In October 1781 , the American forces began the battle for Yorktown , and after a siege that lasted eight days , Lord Cornwallis capitulated on October 19 Figure . Tradition says that during the surrender ofhis troops , the British band played The World Turned Upside Down , a song that the Empire unexpected reversal of fortune .

154 America War for Independence , FIGURE The 1820 painting above , by John Trumbull , is titled Surrender of Lord Cornwallis , but Cornwallis actually sent his general , Charles , to perform the ceremonial surrendering of the sword . The painting depicts General Benjamin Lincoln holding out his hand to receive the sword . General George Washington is in the background on the brown horse , since he refused to accept the sword from anyone but Cornwallis himself . DEFINING AMERICAN The World Turned Upside Down The World Turned Upside Down , reputedly played during the surrender of the British at Yorktown , was a traditional English ballad from the seventeenth century . It was also the theme of a popular British print that circulated in the 17905 Figure . FIGURE In many of the images in this popular print , entitled The World Turned Upside Down or the Folly of Man , animals and humans have switched places . In one , children take care oftheir parents , while in another , the sun , moon , and stars appear below the earth . Why do you think these images were popular in Great Britain in the decade following the Revolutionary War ?

What would these images imply to Americans ?

CLICK AND EXPLORE Visit the Public Domain Review ( to explore the images in an century British chapbook ( a pamphlet for tracts or ballads ) titled The World Turned Upside Down . The chapbook is illustrated with woodcuts similar to those in the popular print mentioned above . Access for free at .

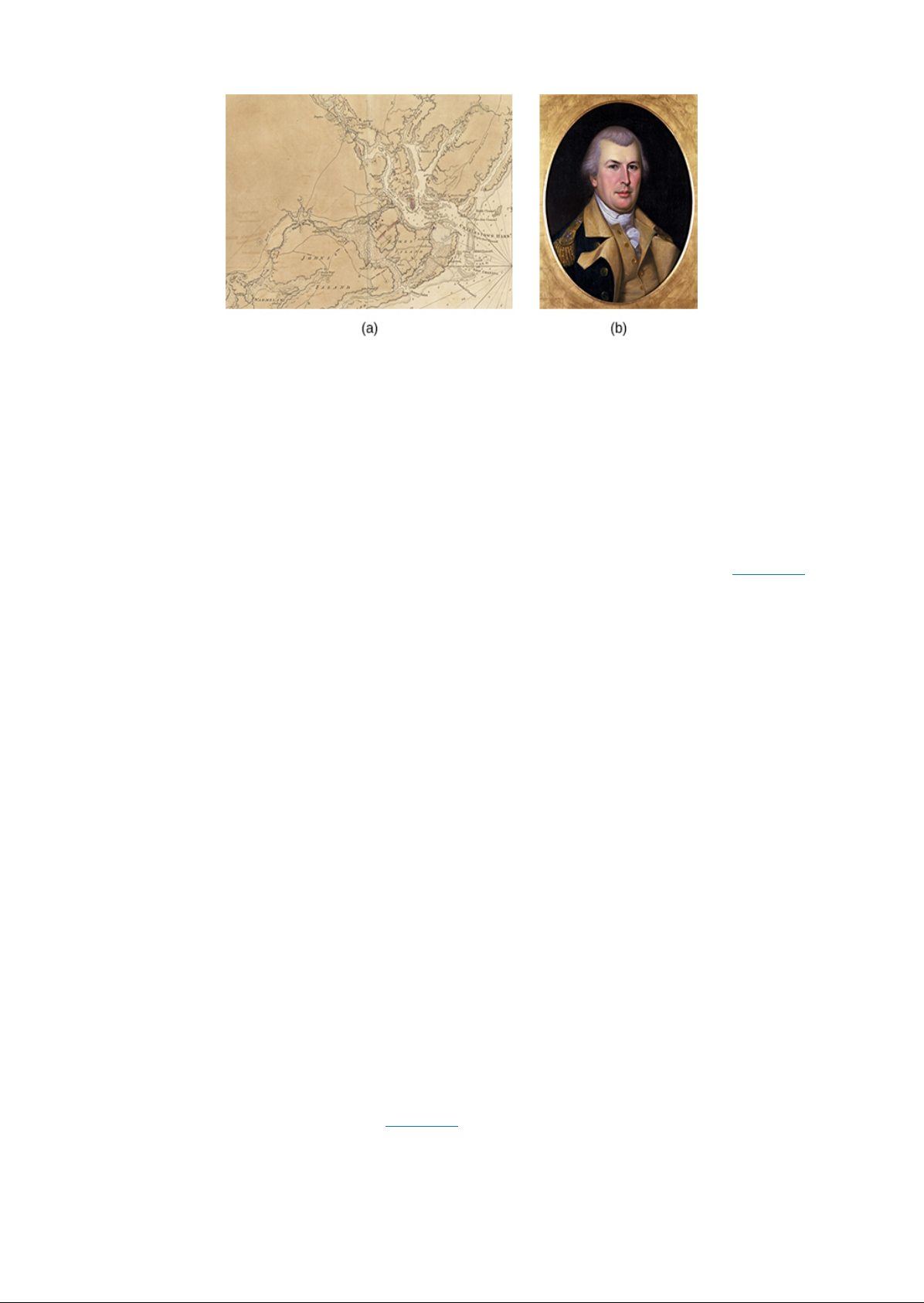

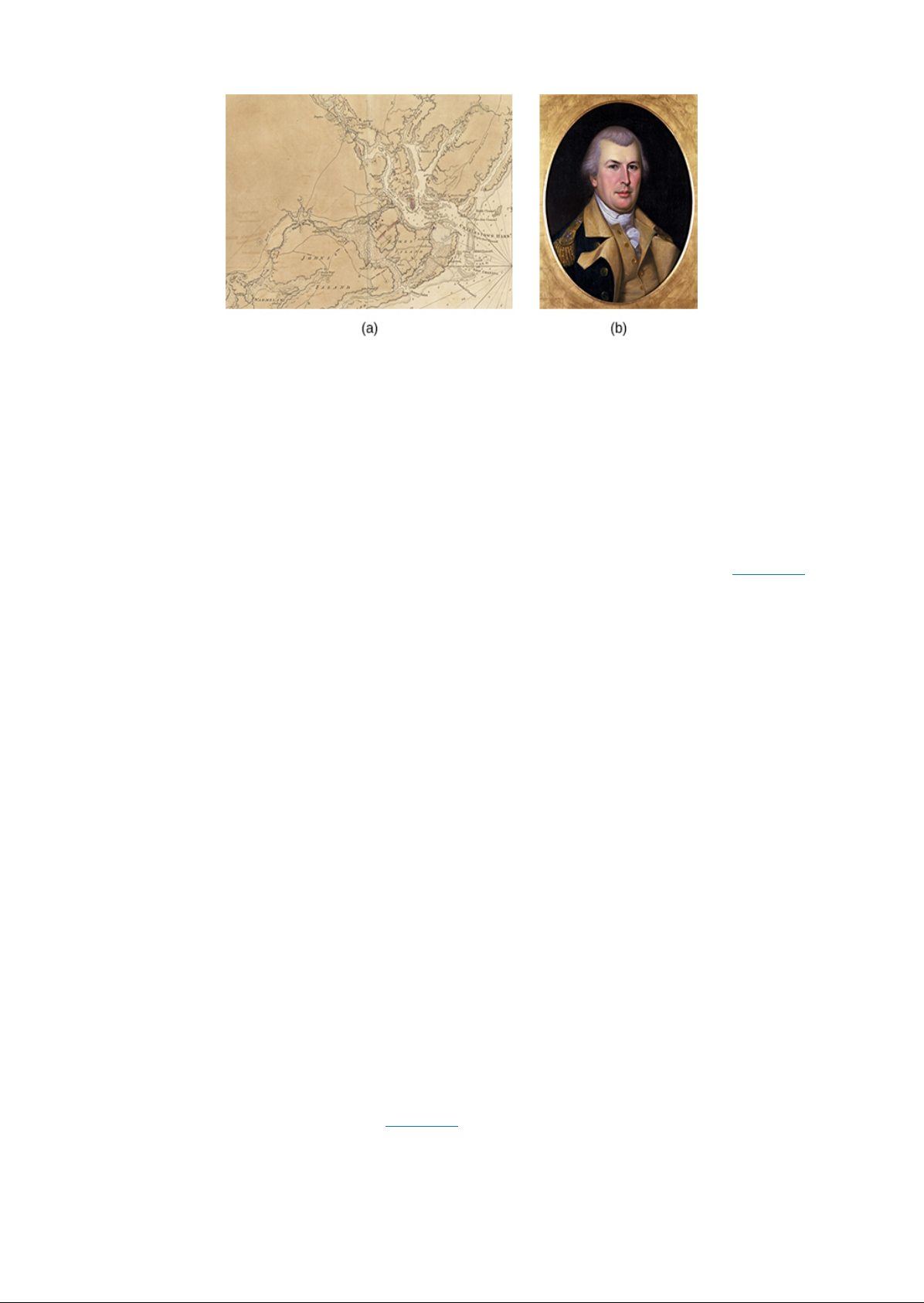

Identity during the American Revolution 155 THE TREATY OF PARIS The British defeat at Yorktown made the outcome of the war all but certain . In light of the American victory , the Parliament of Great Britain voted to end further military operations against the rebels and to begin peace negotiations . Support for the war effort had come to an end , and British military forces began to evacuate the former American colonies in 1782 . When hostilities had ended , Washington resigned as commander in chief and returned to his Virginia home . In April 1782 , Benjamin Franklin , John Adams , and John Jay had begun informal peace negotiations in Paris . from Great Britain and the United States the treaty in 1783 , signing the Treaty of Paris Figure in September of that year . The treaty recognized the independence of the United States placed the western , eastern , northern , and southern boundaries of the nation at the Mississippi River , the Atlantic Ocean , Canada , and Florida , respectively and gave New Englanders rights in the waters off Newfoundland . Under the terms of the treaty , individual states were encouraged to refrain from persecuting Loyalists and to return their property . FIGURE The last page of the Treaty of Paris , signed on September , 1783 , contained the signatures and seals of representatives for both the British and the Americans . From right to left , the seals pictured belong to David Hartley , who represented Great Britain , and John Adams , Benjamin Franklin , and John Jay for the Americans . Identity during the American Revolution LEARNING OBJECTIVES By the end ofthis section , you will be able to Explain Loyalist and Patriot sentiments Identify different groups that participated in the Revolutionary War The American Revolution in effect created multiple civil wars . Many of the resentments and that fed these predated the Revolution , and the outbreak of war acted as the catalyst they needed to burst forth . In particular , the middle colonies of New York , New Jersey , and Pennsylvania had deeply divided populations . Loyalty to Great Britain came in many forms , from wealthy elites who enjoyed the prewar status quo to escaped enslaved people who desired the freedom that the British offered . LOYALISTS Historians disagree on what percentage of colonists were Loyalists estimates range from 20 percent to over 30 percent . In general , however , of British America population of million , roughly remained loyal

156 America War for Independence , to Great Britain , while another third committed themselves to the cause of independence . The remaining third remained apathetic , content to continue with their daily lives as best they could and preferring not to engage in the struggle . Many Loyalists were royal and merchants with extensive business ties to Great Britain , who viewed themselves as the rightful and just defenders of the British constitution . Others simply resented local business and political rivals who supported the Revolution , viewing the rebe as hypocrites and schemers who used the break with the Empire to increase their fortunes . In New York Hudson Valley , animosity among the tenants of estates owned by Revolutionary leaders turned them to tie cause of King and Empire . During the war , all the states passed acts , which gave he new revolutionary governments in the former colonies the right to seize Loyalist land and property . To ferret out Loyalists , revolutionary governments also passed laws requiring the male population to take oaths of allegiance to the new states . Those who refused lost their property and were often imprisoned or made to work for he new local revolutionary order . William Franklin , Benjamin Franklin only surviving son , remained loyal to Crown and Empire and served as royal governor of New Jersey , a post he secured with his father he During the war , revolutionaries imprisoned William in Connecticut however , he remained steadfast in his allegiance to Great Britain and moved to England after the Revolution . He and his father never reconciled . As many as nineteen thousand colonists served the British in the fort to put down the rebellion , and after the Revolution , as many as colonists left , moving to England or north to Canada rather than staying in the new United States ( Figure ) Eight thousand White people and ive thousand free Black people went to Britain . Over thirty thousand went to Canada , transforming that na ion from predominately French to predominantly British . Another sizable group of Loyalists went to the British West Indies , taking enslaved people with them . FIGURE The Coming of the Loyalists , a ca . 1880 work that artist Henry created at least a century after the Revolution , shows colonists arriving by ship in New Brunswick , Canada . MY STORY Hannah on Removing to Nova Scotia Hannah was eleven years old in 1783 , when her Loyalist family removed from New York to Ste . Point in the colony of Nova Scotia . Later in life , she compiled her memories of that time . Access for free at .

Identity during the American Revolution 157 Father said we were to go to Nova Scotia , that a ship was ready to take us there , so we made all haste to get ready . Then on Tuesday , suddenly the house was surrounded by rebels and father was taken prisoner and carried away . When morning came , they said he was free to go . We had wagon loads carried down the Hudson in a sloop and then we went on board the transport that was to bring us to Saint John . I was just eleven years old when we left our farm to come here . It was the last transport of the season and had on board all those who could not come sooner . The transports had come in May so the people had all the summer before them to get settled . We lived in a tent at Anne got a house ready . There was no floor laid , no windows , no chimney , no door , but we had a roof at least . A good was blazing and mother had a big loaf of bread and she boiled a kettle of water and put a good piece of butter in a pewter bowl . We toasted the bread and all sat around the bowl and ate our breakfast that morning and mother said Thank God we are no longer in dread of having shots through our house . This is the sweetest meal I ever tasted for many a day . What do these excerpts tell you about life as a Loyalist in New York or as a transplant to Canada ?

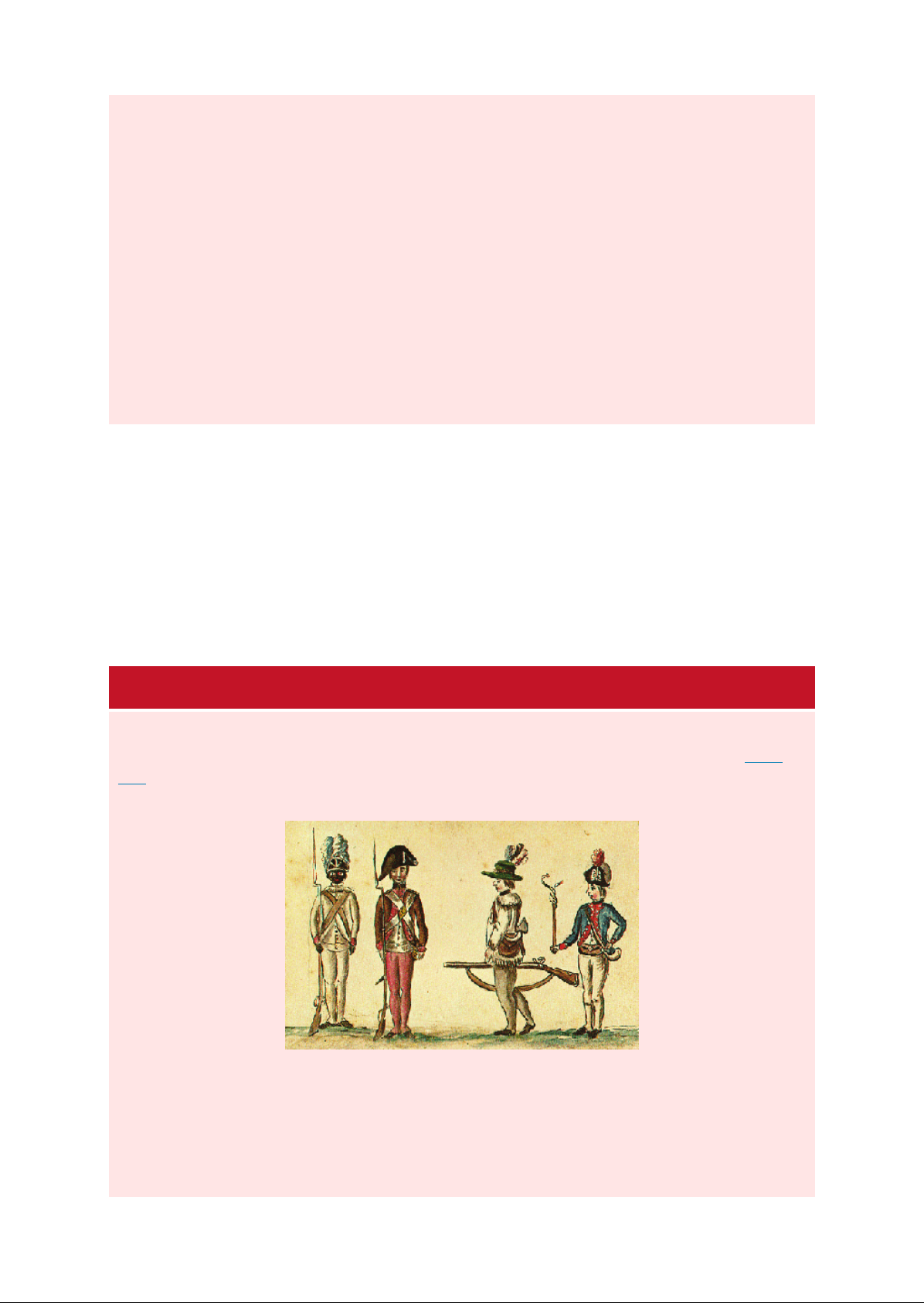

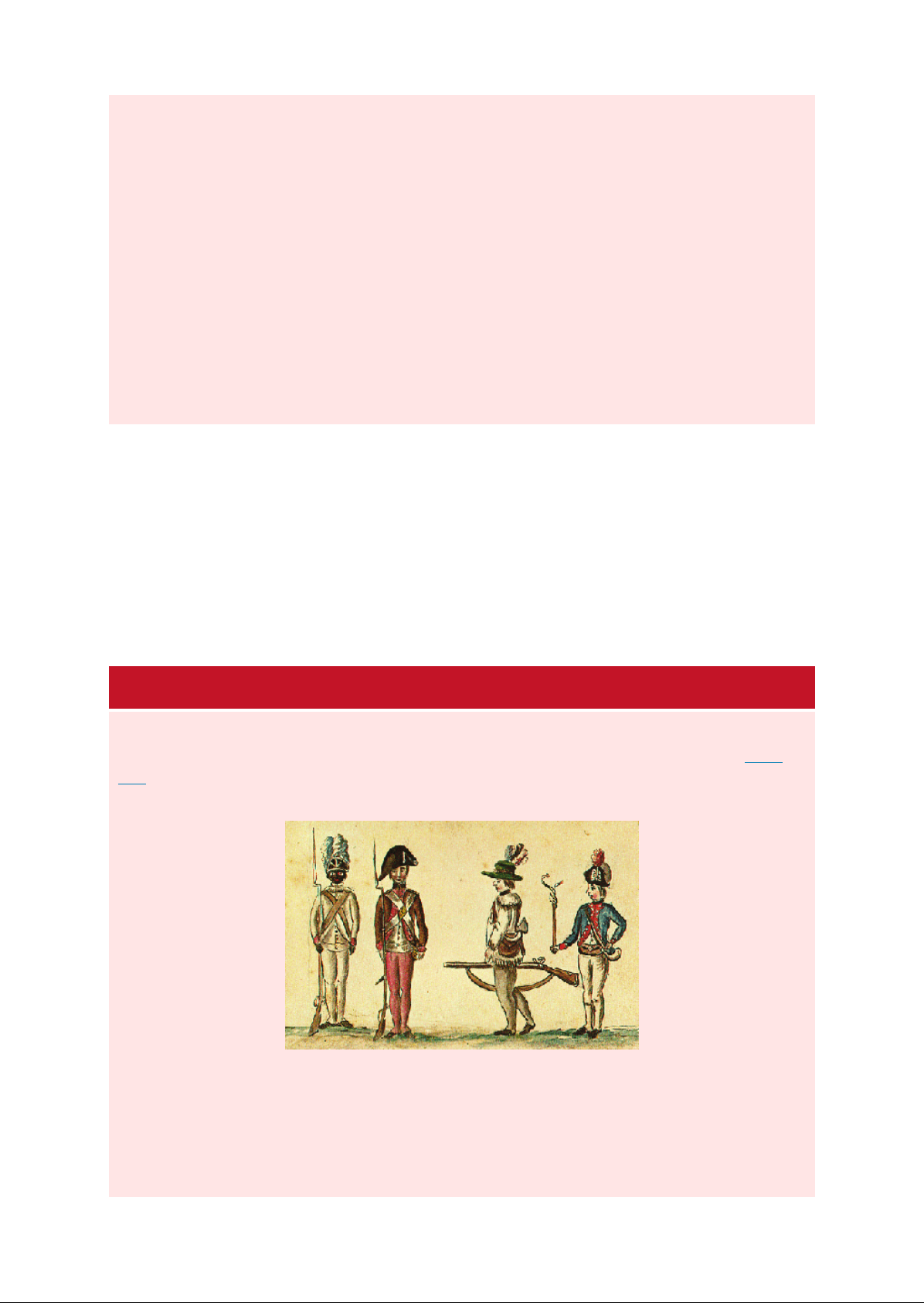

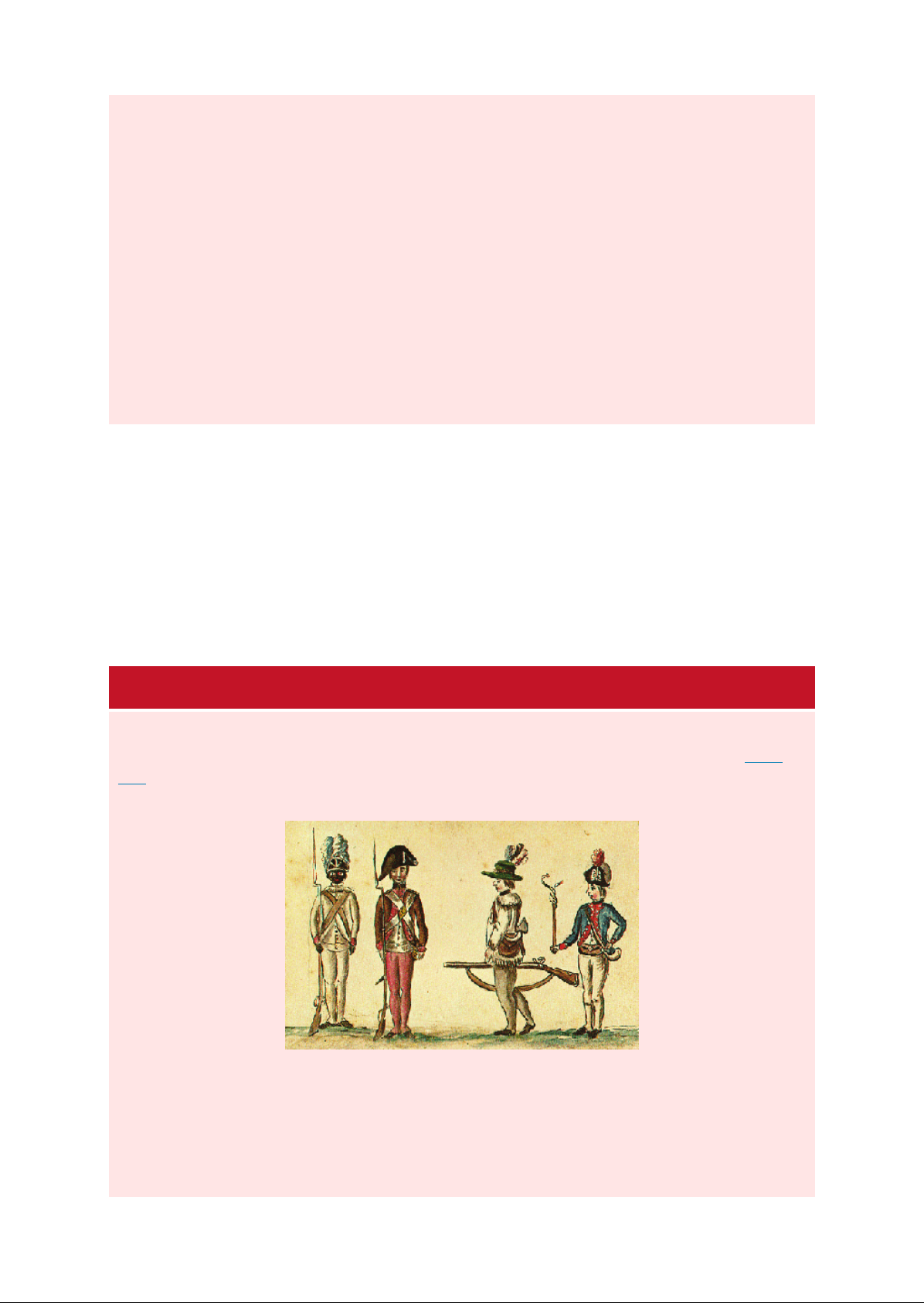

ENSLAVED PEOPLE AND NATIVE PEOPLE While some enslaved people who fought for the Patriot cause received their freedom , revolutionary the not grant these allies their freedom as a matter of course . Washington , the enslaver of more than two hundred people during the Revolution , refused to let enslaved people serve in the army , although he did allow free Black people to serve . In his will , Washington did free the people he enslaved . In the new United States , the Revolution largely reinforced a racial identity based on skin color . Whiteness , now a national identity , denoted freedom and stood as the key to power . Blackness , more than ever before , denoted servile status . Indeed , despite their class and ethnic differences , White revolutionaries stood mostly united in their hostility to both Black and Native Americans . MY STORY and Boston King on the Revolutionary War In the Revolutionary War , some Black people , both free and enslaved , chose to for the Americans ( Egg ) Others chose to for the British , who offered them freedom for joining their cause . Read the excerpts below for the perspective of a Black veteran from each side of the conflict . FIGURE . de Verger created this 1781 watercolor , which depicts American soldiers at the Siege of Yorktown . Verger was an in Rochambeau army , and his diary holds accounts of his experiences in the campaigns of 1780 and 1781 . This image contains one ofthe earliest known representations of a Black Continental soldier . was captured in Africa at age sixteen and brought to America . He joined the Patriot forces and

158 America War for Independence , was honorably discharged and emancipated after the war . He told his story to Benjamin Prentiss , who published it as The Slave in 1810 . Finally , I was in the battles at Cambridge , White Plains , Princeton , Newark , Frog Point , where I had a ball pass through my knapsack . All which sic the reader can obtain a more perfect account of in history , than I can give . At last we returned to West Point and were discharged 1783 , as the war was over . Thus was I , a slave for years for liberty . After we were disbanded , I returned to my old master at Connecticut , with whom I lived one year , my services in the American war , having emancipated me from further slavery , and from being bartered or sold . Here I enjoyed the pleasures of a freeman my food was sweet , my labor pleasure and one bright gleam of life seemed to shine upon me . Boston King was a enslaved man who escaped his captor and joined the Loyalists . He made his way to Nova Scotia and later Sierra Leone , where he published his memoirs in 1792 . The excerpt below describes his experience in New York after the war . When I arrived at , my friends rejoiced to see me once more restored to liberty , and joined me in praising the Lord for his mercy and goodness . In 1783 the horrors and devastation of war happily terminated , and peace was restored between America and Great Britain , which diffused among all parties , except us , who had escaped from slavery and taken refuge in the English army for a report prevailed at , that all the slaves , in number 2000 , were to be delivered up to their masters , altho some of them had been three or four years English , This dreadful rumour us all with inexpressible anguish and terror , especially when we saw our old masters comingfrom Virginia , and other parts , and seizing upon their slaves in the streets of , or even dragging them out of their beds . Many of the slaves had very cruel masters , so that the thoughts of returning home with them embittered life to us , For some days we lost our appetite for food , and sleep departed from our eyes . The English had compassion upon us in the day of distress , and issued out a Proclamation , importing , That all slaves should be free , who had taken refuge in the British lines , and claimed the sanction and privileges of the Proclamations respecting the security and protection of Negroes . In consequence of this , each of us received a from the commanding officer at , which dispelled all our fears , and us with joy and gratitude , What do these two narratives have in common , and how are they different ?

How do he two men describe freedom ?

For enslaved people willing to run away and join the British , the American ion offered a unique occasion to escape bondage . Of the halfa million enslaved people in the American colonies during the Revolution , twenty thousand joined the British cause . At Yorktown , for instance , thousands of Black troops fought with Lord Cornwallis . People enslaved by George Washington , Thomas Jefferson , Patrick Henry , and other revolutionaries seized the opportunity for freedom and to the British sic Between ten and twenty thousand enslaved people gained their freedom because of the Revolution arguably , the Revolution created the largest slave uprising and the greatest emancipation until the Civil War . After tie Revolution , some of these African Loyalists emigrated to Sierra Leone on the west coast of Africa . Others removed to Canada and England . It is also true that people of color made heroic contributions to the cause of American independence . However , while the British offered freedom , most American revolutionaries clung notions of Black inferiority . Powerful Native peoples who had allied themselves with the British , including the Mohawk and the Creek , also remained loyal to the Empire . A Mohawk named Joseph Brant , whose given name was ( rose to prominence while for the British during the Revolution . He joined forces with Colonel Barry Leger during the 1777 campaign , which ended with the surrender of General Burgoyne at Saratoga . After the war , Brant moved to the Six Nations reserve in Canada . From his home on the shores of Lake Ontario , he remained active in efforts to restrict White encroachment onto Native lands . After their defeat , the British Access for free at .

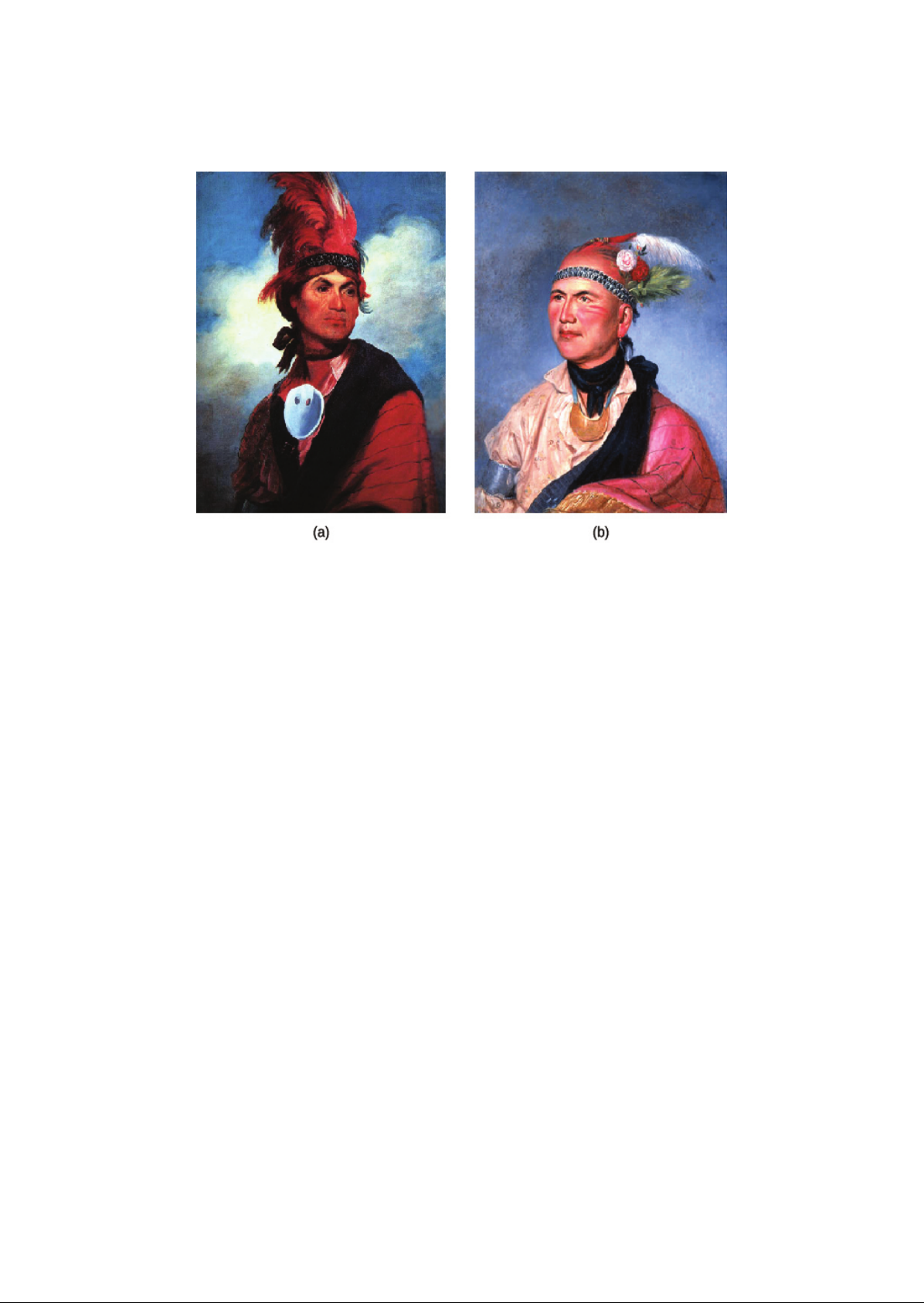

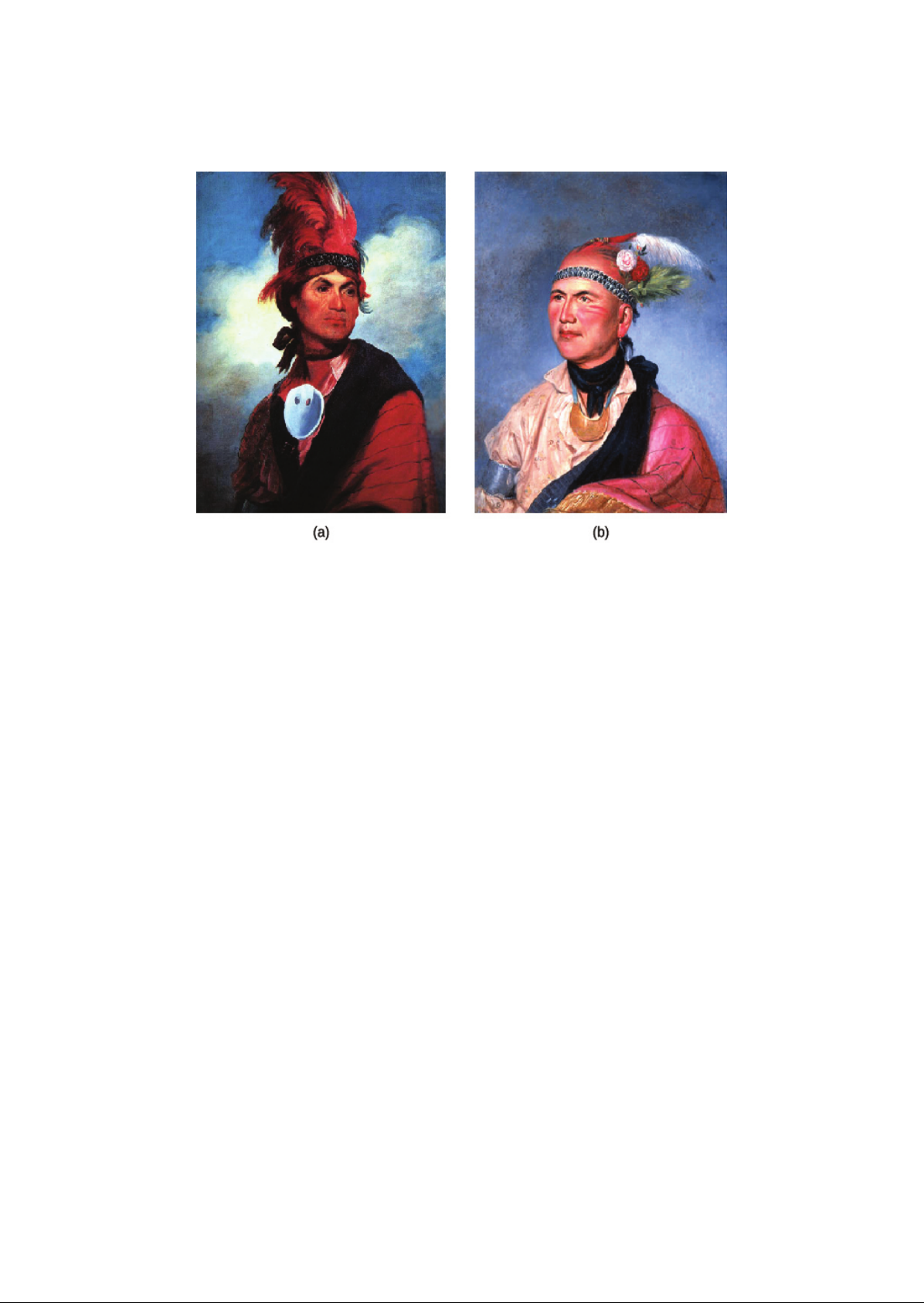

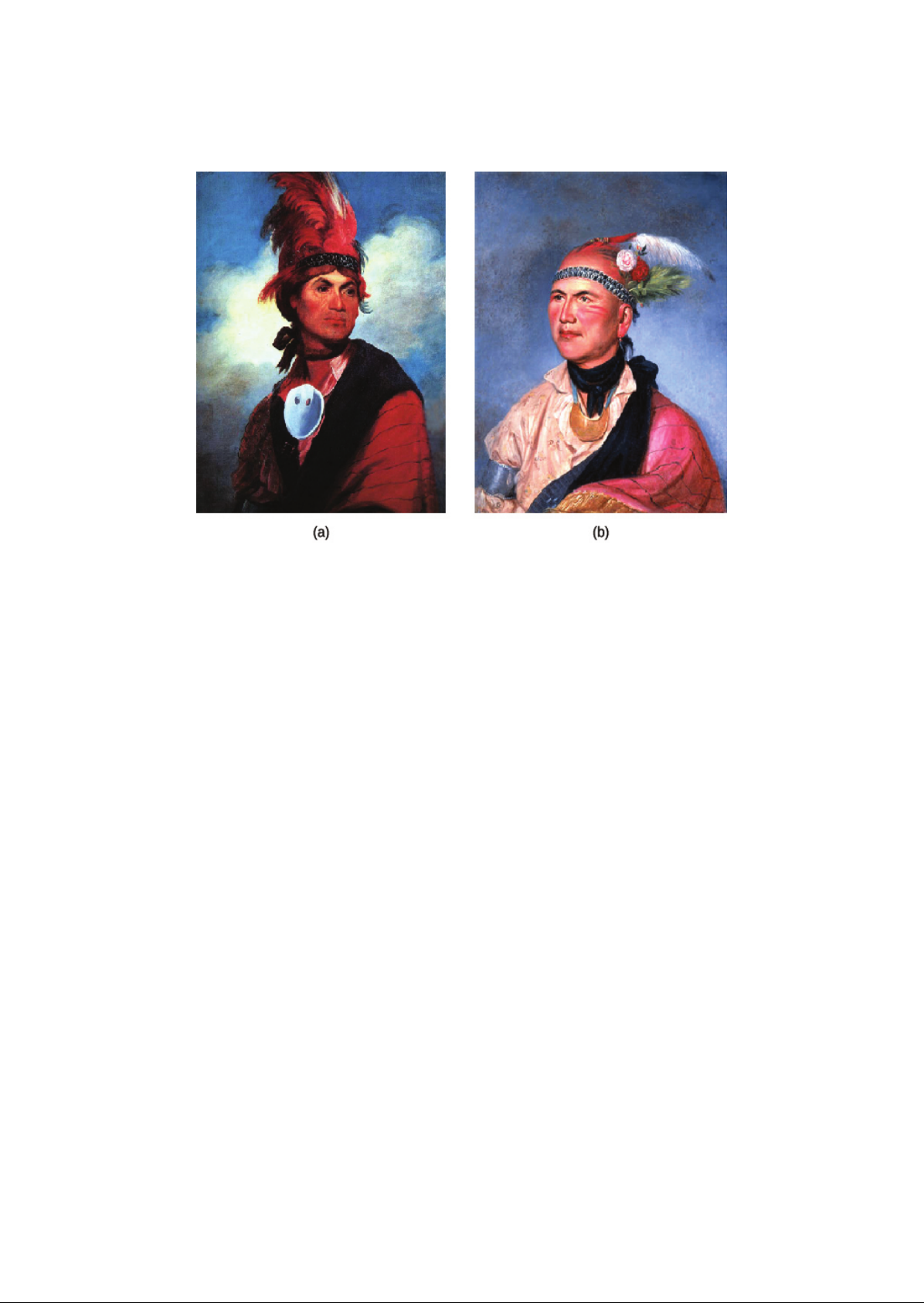

Identity during the American Revolution did not keep promises they made to help their Native American allies keep their territory in fact , the Treaty of Paris granted the United States huge amounts of supposedly regions that were actually Native lands . FIGURE What similarities can you see in these two portraits of Joseph Brant , one by Gilbert Stuart in 1786 ( a ) and one by Charles Wilson in 1797 ( What are the differences ?

Why do you think the artists made the choices they did ?

PATRIOTS The American revolutionaries ( also called Patriots or ) came from many different backgrounds and included merchants , shoemakers , farmers , and sailors . What is extraordinary is the way in which the struggle for independence brought a vast of society together , animated by a common cause . During the war , the revolutionaries faced great , including massive supply problems clothing , ammunition , tents , and equipment were all hard to come by . After an initial burst of enthusiasm in 1775 and 1776 , the shortage of supplies became acute in 1777 through 1779 , as Washington winter at Valley Forge demonstrates . Funding the war effort also proved very . Whereas the British could pay in gold and silver , the American forces relied on paper money , backed by loans obtained in Europe . This American money was called Continental currency unfortunately , it quickly fell in value . Not worth a Continental soon became a shorthand term for something of no value . The new revolutionary government printed a great amount of this paper money , resulting in runaway . By 1781 , was such that 146 Continental dollars were worth only one dollar in gold . The problem grew worse as each former colony , now a revolutionary state , printed its own currency . WOMEN In colonial America , women shouldered enormous domestic and responsibilities . The war for independence only increased their workload and , in some ways , their roles . Rebel leaders required women to produce articles for from clothing to also keeping their homesteads going . This was not an easy task when their husbands and sons were away . Women were also expected to provide food and lodging for armies and to nurse wounded soldiers . The Revolution opened some new doors for women , however , as they took on public roles usually reserved for men . The Daughters of Liberty , an informal organization formed in the to oppose British 159

160 America War for Independence , raising measures , worked tirelessly to support the war effort . Esther Reed of Philadelphia , wife of Governor Joseph Reed , formed the Ladies Association of Philadelphia and led a fundraising drive to provide sorely needed supplies to the Continental Army . In The Sentiments of an American Woman ( 1780 ) she wrote to other women , The time is arrived to display the same sentiments which animated us at the beginning of the Revolution , when we renounced the use of teas , however agreeable to our taste , rather than receive them from our persecutors when we made it appear to them that we placed former necessaries in the rank of , when our liberty was interested when our republican and laborious hands spun the , prepared the linen intended for the use of our soldiers when exiles and fugitives we supported with courage all the evils which are the of war . Reed and other women in Philadelphia raised almost in Continental money for the war . CLICK AND EXPLORE Read the entire text of Esther Reed The Sentiments of an American Woman ( on a page hosted by the University of . Women who did not share Reed prominent status nevertheless played key economic roles by producing homespun cloth and food . During shortages , some women formed mobs and wrested supplies from those who hoarded them . Crowds of women beset merchants and demanded fair prices for goods if a merchant refused , a riot would ensue . Still other women accompanied the army as camp followers , serving as cooks , washerwomen , and nurses . A few also took part in combat and proved their equality with men through violence against the hated British . Access for free at .

Key Terms 161 Key Terms acts acts that made it legal for state governments to seize Loyalists property Continental currency the paper currency that the Continental government printed to fund the Revolution Dunmore Proclamation the decree signed by Lord Dunmore , the royal governor of Virginia , which proclaimed that any enslaved or indentured servants who fought on the side of the British would be rewarded with their freedom Hessians German mercenaries hired by Great Britain to put down the American rebellion Resolves North Carolina declaration of rebellion against Great Britain minutemen colonial militias prepared to mobilize and the British with a minute notice popular sovereignty the practice of allowing the citizens of a state or territory to decide issues based on the principle of majority rule republicanism a political philosophy that holds that states should be governed by representatives , not a monarch as a social philosophy , republicanism required civic virtue of its citizens thirteen colonies the British colonies in North America that declared independence from Great Britain in 1776 , which included Connecticut , Delaware , Georgia , Maryland , the province of Massachusetts Bay , New Hampshire , New Jersey , New York , North Carolina , Pennsylvania , Rhode Island and Providence Plantations , South Carolina , and Virginia Yorktown the Virginia port where British General Cornwallis surrendered to American forces Summary Britain Strategy and Its Consequences Until Parliament passed the Coercive Acts in 1774 , most colonists still thought of themselves as proud subjects of the strong British Empire . However , the Coercive ( or Intolerable ) Acts , which Parliament enacted to punish Massachusetts for failing to pay for the destruction of the tea , convinced many colonists that Great Britain was indeed threatening to their liberty . In Massachusetts and other New England colonies , militias like the minutemen prepared for war by stockpiling weapons and ammunition . After the loss of life at the battles of Lexington and Concord in April 1775 , skirmishes continued throughout the colonies . When Congress met in Philadelphia in July 1776 , its members signed the Declaration of Independence , breaking ties with Great Britain and declaring their intention to be . The Early Years ofthe Revolution The British successfully implemented the part of their strategy to isolate New England when they took New York City in the fall of 1776 . For the next seven years , they used New York as a base of operations , expanding heir control to Philadelphia in the winter of 1777 . After suffering through a terrible winter in in Valley Forge , Pennsylvania , American forces were revived with help from Baron von , a Prussian military who helped transform the Continental Army into a professional force . The effort to cu off New England from the rest of the colonies failed with the General Burgoyne surrender at Saratoga in October 1777 . After Saratoga , the struggle for independence gained a powerful ally when France agreed to recognize the United States as a new nation and began to send military support . The entrance archrival in the contest of global the American helped to turn the tide of he war in favor of the revolutionaries . War in the South The British gained momentum in the war when they turned their military efforts against the southern colonies . scored repeated victories in the coastal towns , where they found legions of supporters , including people escaping bondage . As in other colonies , however , control of major seaports did not mean the British cou control the interior . Fighting in the southern colonies devolved into a merciless civil war as the Revolution opened the of anger and resentment between frontier residents and those along

162 Review Questions the coastal regions . The southern campaign came to an end at Yorktown when Cornwallis surrendered to American forces . Identity during the American Revolution The American Revolution divided the colonists as much as it united them , with Loyalists ( or Tories ) joining the British forces against the Patriots ( or revolutionaries ) Both sides included a broad of the population . However , Great Britain was able to convince many to join its forces by promising them freedom , something the southern revolutionaries would not agree to do . The war provided new opportunities , as well as new challenges , for enslaved and free Black people , women , and Native peoples . After the war , many Loyalists the American colonies , heading across the Atlantic to England , north to Canada , or south to the West Indies . Review Questions . How did British General Thomas Gage attempt to deal with the uprising in Massachusetts in 1774 ?

A . He offered the rebels land on the Maine frontier in return for loyalty to England . He allowed for town meetings in an attempt to appease the rebels . He attempted to seize arms and munitions from the colonial insurgents . He ordered his troops to burn Boston to the ground to show the determination of Britain . Which of the following was nota result of Dunmore Proclamation ?

Enslaved people joined Dunmore to for the British . A majority of enslaved people in the colonies won their freedom . Patriot forces increased their commitment to independence . Both slaveholding and White people feared a rebellion . Which of the following is of a republic ?

A . A republic has no hereditary ruling class . A republic relies on the principle of popular sovereignty . Representatives chosen by the people lead the republic . A republic is governed by a monarch and the royal he or she appoints . Wha are the main arguments that Thomas Paine makes in his pamphlet Common Sense ?

Why was this pain so popular ?

Which city served as the base for British operations for most of the war ?

A . New York Saratoga . Wha battle turned the tide of war in favor of the Americans ?

he Battle of Saratoga he Battle of Brandywine Creek he Battle of White Plains he Battle of Valley Forge Access for free at .

Critical Thinking Questions 163 . Which term describes German soldiers hired by Great Britain to put down the American rebellion ?

Patriots Royalists Hessians Loyalists . Describe the British strategy in the early years of the war and explain whether or not it succeeded . How did George Washington military tactics help him to achieve success ?

10 . Which American general is responsible for improving the American military position in the South ?

John Burgoyne Greene Wilhelm Frederick von Charles Cornwallis 11 . Describe the British southern strategy and its results . 12 . Which of the following statements best represents the division between Patriots and Loyalists ?

A . Most American colonists were Patriots , with only a few traditionalists remaining loyal to the King and Empire . Most American colonists were Loyalists , with only a few revolutionaries leading the charge for independence . American colonists were divided among those who wanted independence , those who wanted to remain part of the British Empire , and those who were neutral . The vast majority of American colonists were neutral and did take a side between Loyalists and Patriots . 13 . Which of the following is not one of the tasks women performed during the Revolution ?

holding government maintaining their homesteads feeding , quartering , and nursing soldiers raising funds for the war effort Critical Thinking Questions 14 . How did tie colonists manage to triumph in their battle for independence despite Great Britain military might ?

If any of these factors had been different , how might it have affected the outcome of the war ?

15 . How did tie condition of certain groups , such as women , Black people , and Native people , reveal a ion in the Declaration of Independence ?

16 . What was the effect and importance of Great Britain promise of freedom to enslaved people who joined the side ?

17 . How did tie Revolutionary War provide both new opportunities and new challenges for enslaved and free Black people in America ?

18 . Describe he ideology of republicanism . As a political philosophy , how did republicanism compare to the system that prevailed in Great Britain ?

19 . Describe he backgrounds and philosophies of Patriots and Loyalists . Why did colonists with such diverse individua interests unite in support of their respective causes ?

What might different groups of Patriots and Loyalists , depending upon their circumstances , have hoped to achieve by winning the war ?

164 Critical Thinking Questions Access for free at .