Americans and the Great War, 1914-1919

Explore the Americans and the Great War, 1914-1919 study material pdf and utilize it for learning all the covered concepts as it always helps in improving the conceptual knowledge.

Americans and the Great War, 1914-1919 PDF Download

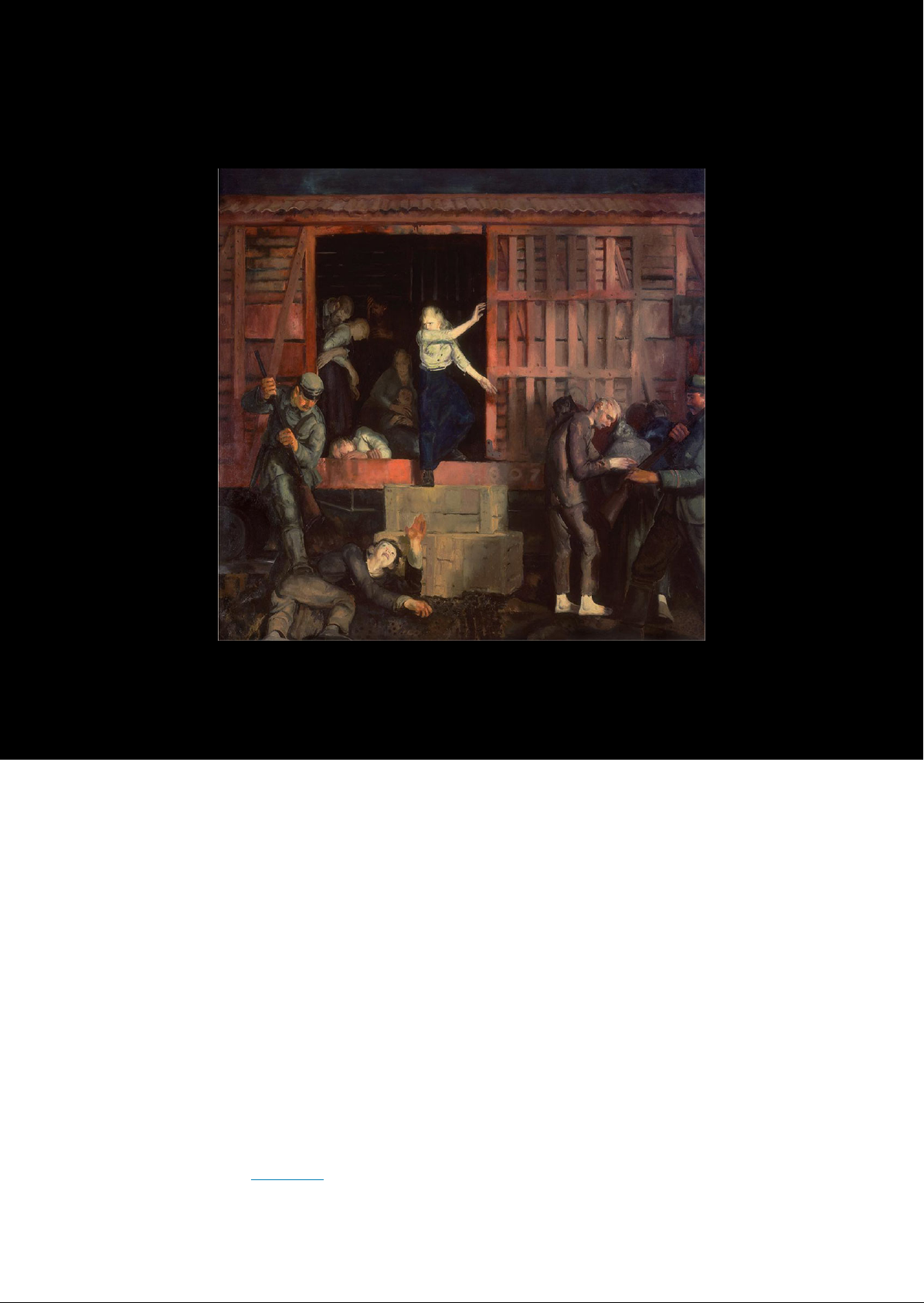

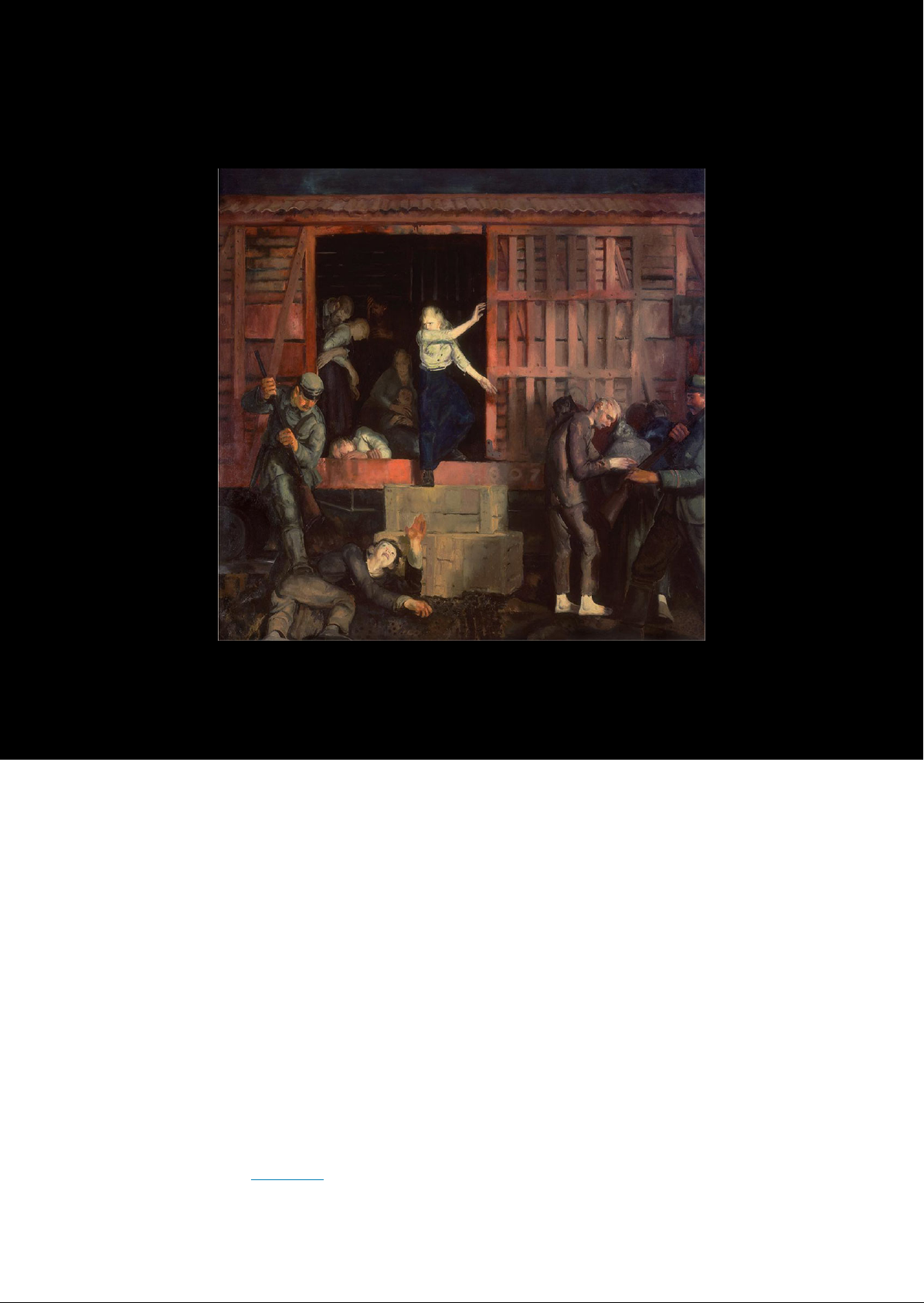

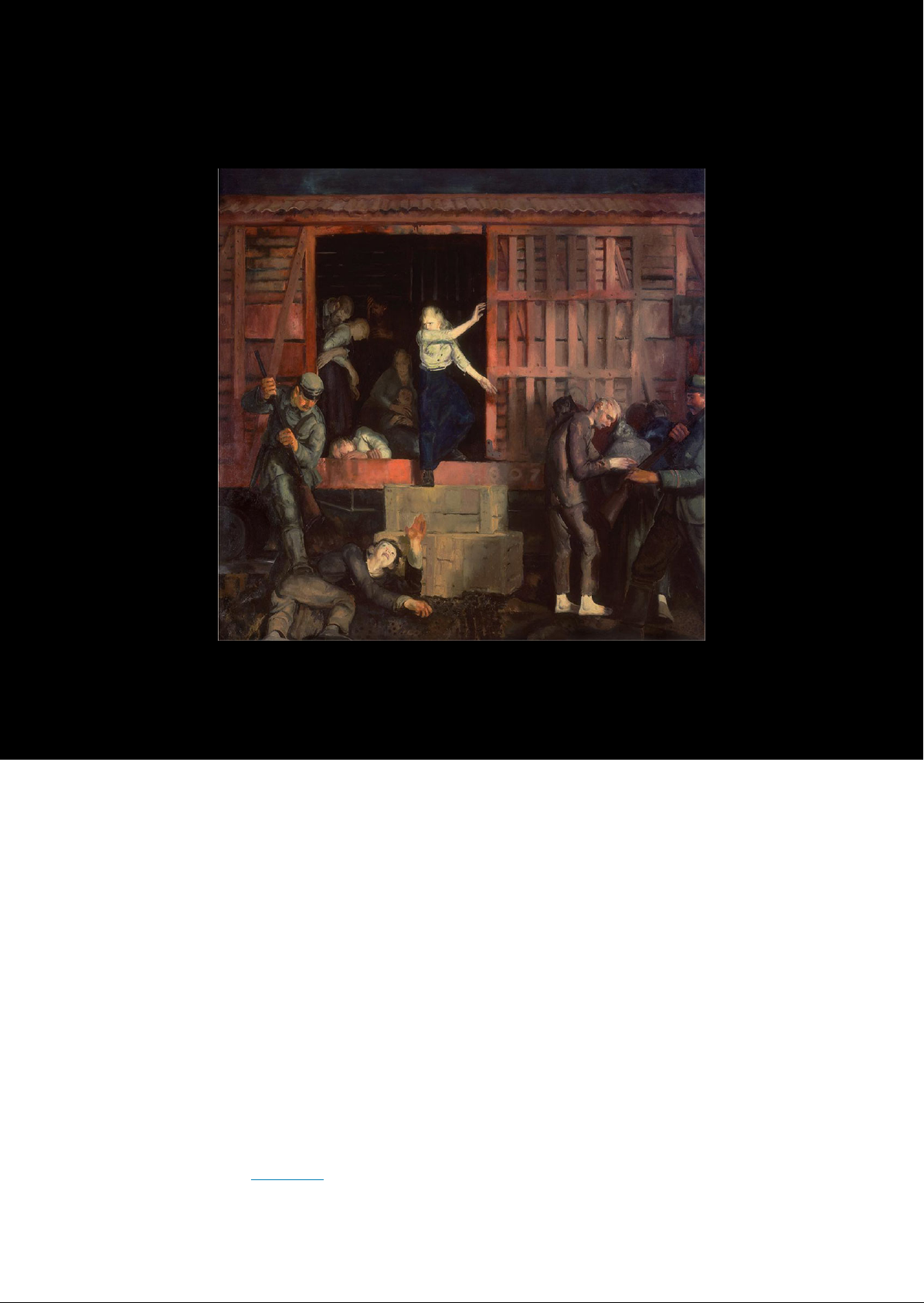

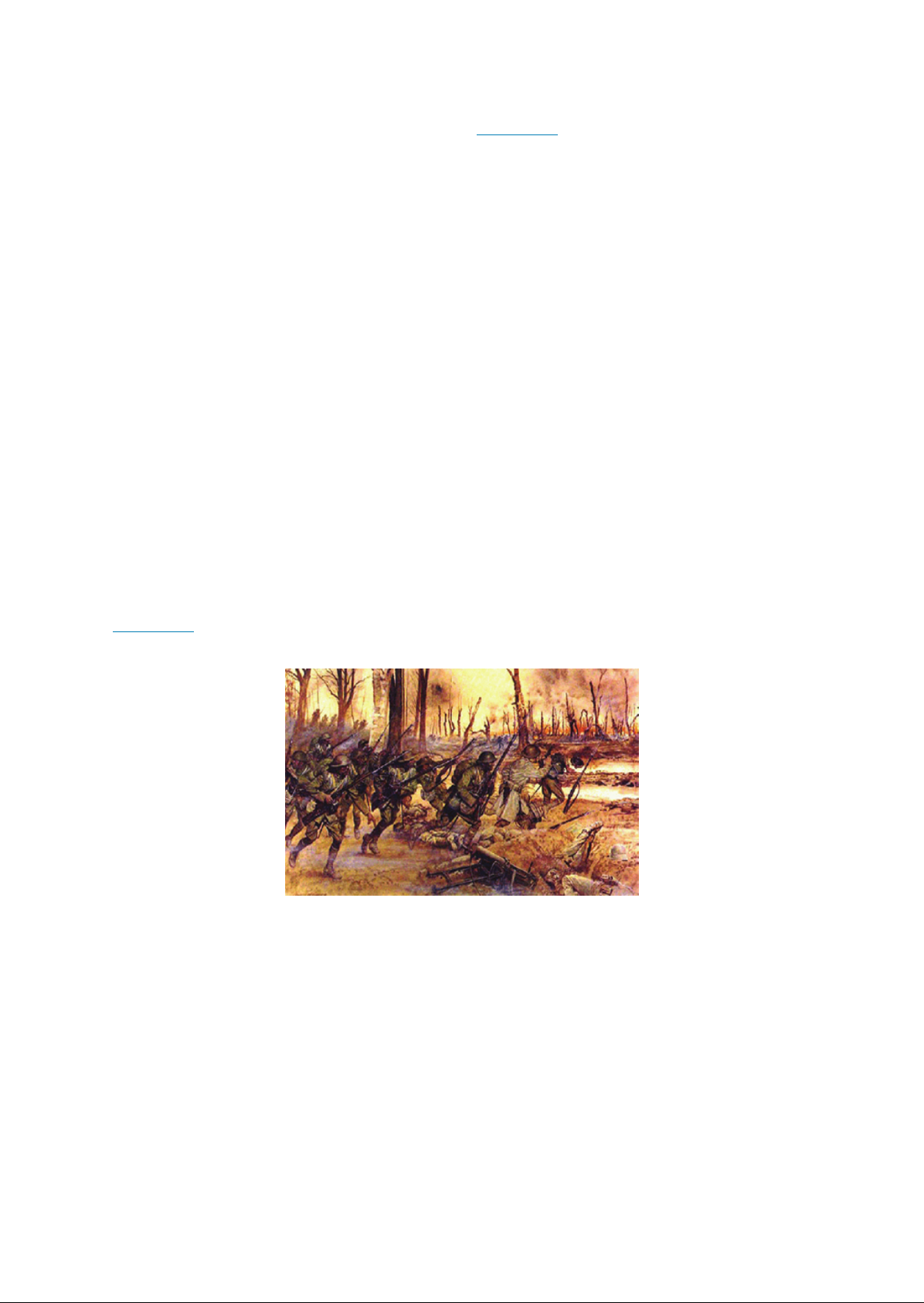

Americans and the Great War , FIGURE Return ofthe Useless ( 1918 ) by George Bellows , is an example of a kind of artistic imagery used to galvanize reluctant Americans into joining World War I . The scene shows German soldiers unloading and mistreating imprisoned civilians after their return home to Belgium from German camps . CHAPTER OUTLINE American Isolationism and the European Origins of War The United States Prepares for War A New Home Front From Peace Demobilization and Its Difficult Aftermath INTRODUCTION On the eve of World War I , the US . government under President Woodrow Wilson opposed any entanglement in international military . But as the war engulfed Europe and the belligerents ' total war strategies targeted commerce and travel across the Atlantic , it became clear that the United States would not be able to maintain its position of neutrality . Still , the American public was of mixed resisted the idea of American intervention and American lives lost , no matter how bad the circumstances . In 1918 , artist George Bellows created a series of paintings intended to strengthen public support for the war effort . His paintings depicted German war explicit and expertly captured detail , from children run through with bayonets to torturer happily resting while their victims suffered . The image above , entitled Return of the Useless Fit shows Germans unloading sick or disabled labor camp prisoners from a boxcar , These paintings , not regarded as Bellows most important artistic work , were typical for

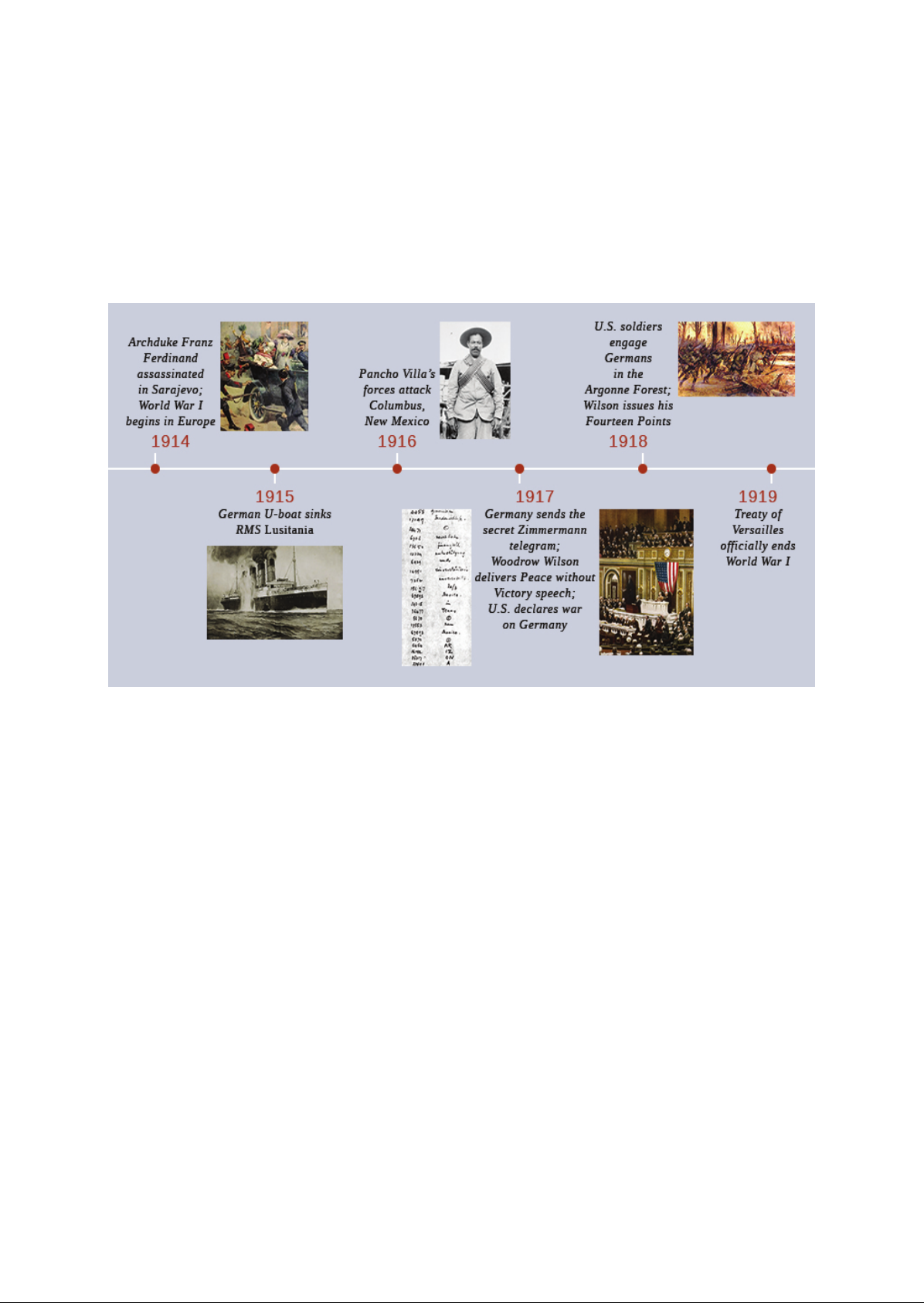

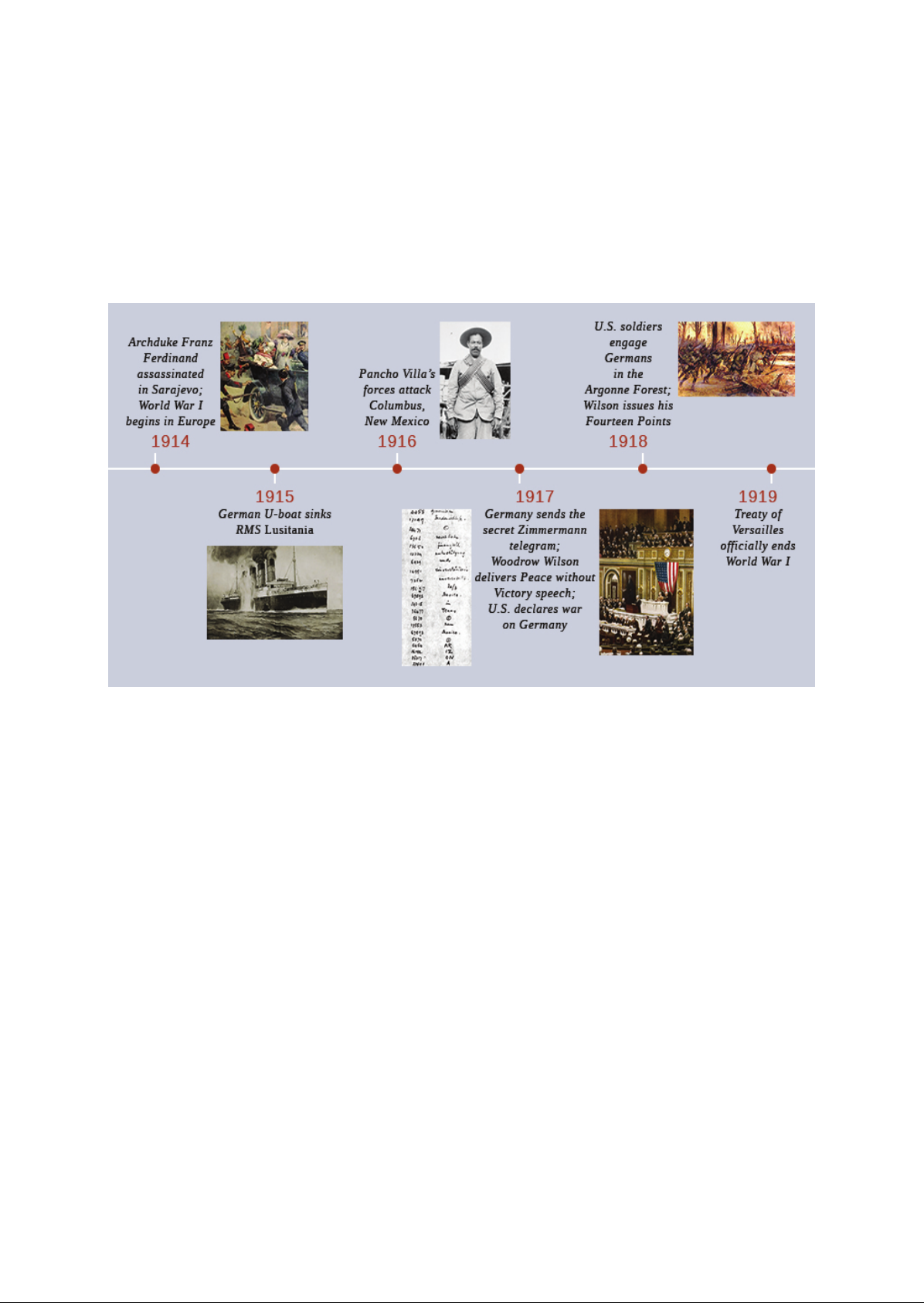

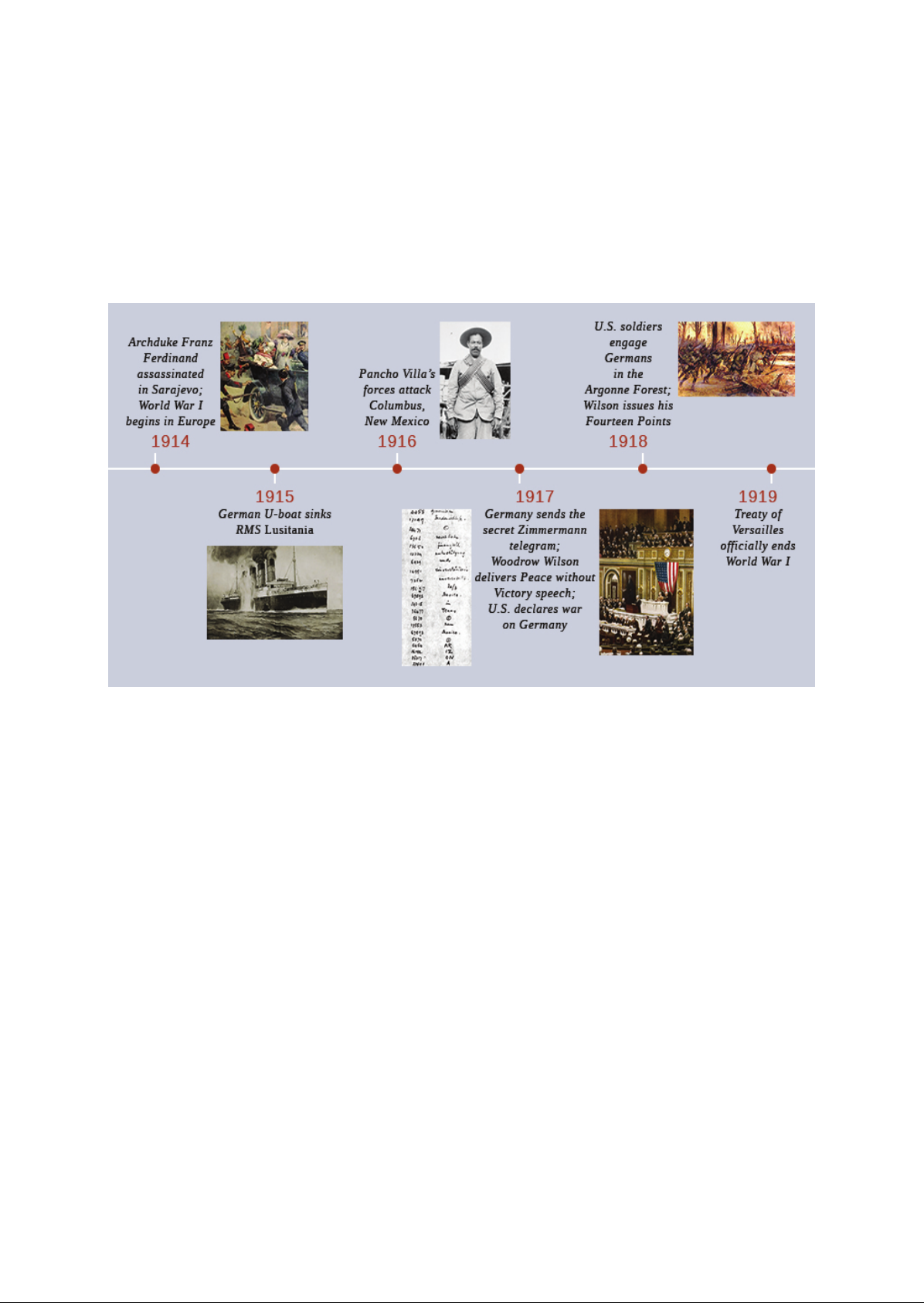

606 23 Americans and the Great War , German propaganda at the time . The government sponsored much of this propaganda out of concern that many American immigrants sympathized with the Central powers and would not support the war effort . American Isolationism and the European Origins of War LEARNING OBJECTIVES By the end ofthis section , you will be able to Explain Woodrow Wilson foreign policy and the of maintaining American neutrality at the outset of World Warl key factors that led to the . declaration of war on Germany in April 1917 soldiers Archduke Franz . I engage Ferdinand , Germans assassinated Pancho ' in the in Sarajevo forces attack Forest World War I Columbus , issues Iris begins in Europe ' New Mexico Fourteen Points 1914 1916 1918 I 1915 1917 19 German sinks 37 , Germany sends the Treaty of secret Versailles telegram ends ?

Woodrow , I World War I delivers Peace without I ) Victory speech In . declares war . on Germany . FIGURE Unlike his immediate predecessors , President Woodrow Wilson had planned to shrink the role of the United States in foreign affairs . He believed that the nation needed to intervene in international events only when there was a moral imperative to do so . But as Europe political situation grew dire , it became increasingly for Wilson to insist that the growing overseas was not America responsibility . Germany war tactics struck most observers as morally reprehensible , while also putting American free trade with the Entente at risk . Despite campaign promises and diplomatic efforts , Wilson could only postpone American involvement in the war . WOODROW EARLY EFFORTS AT FOREIGN POLICY When Woodrow Wilson took over the White House in March 1913 , he promised a less expansionist approach to American foreign policy than Theodore Roosevelt and William Howard Taft had pursued . Wilson did share the commonly held view that American values were superior to those of the rest of the world , that democracy was the best system to promote peace and stability , and that the United States should continue to actively pursue economic markets abroad . But he proposed an idealistic foreign policy based on morality , rather than American , and felt that American interference in another nation affairs should occur only when the circumstances rose to the level of a moral imperative . Wilson appointed former presidential candidate William Jennings Bryan , a noted and proponent of world peace , as his Secretary of State . Bryan undertook his new assignment with great vigor , encouraging nations around the world to sign cooling off treaties , under which they agreed to resolve international disputes through talks , not war , and to submit any grievances to an international commission . Bryan also negotiated friendly relations with Colombia , including a 25 million apology for Roosevelt actions Access for free at .

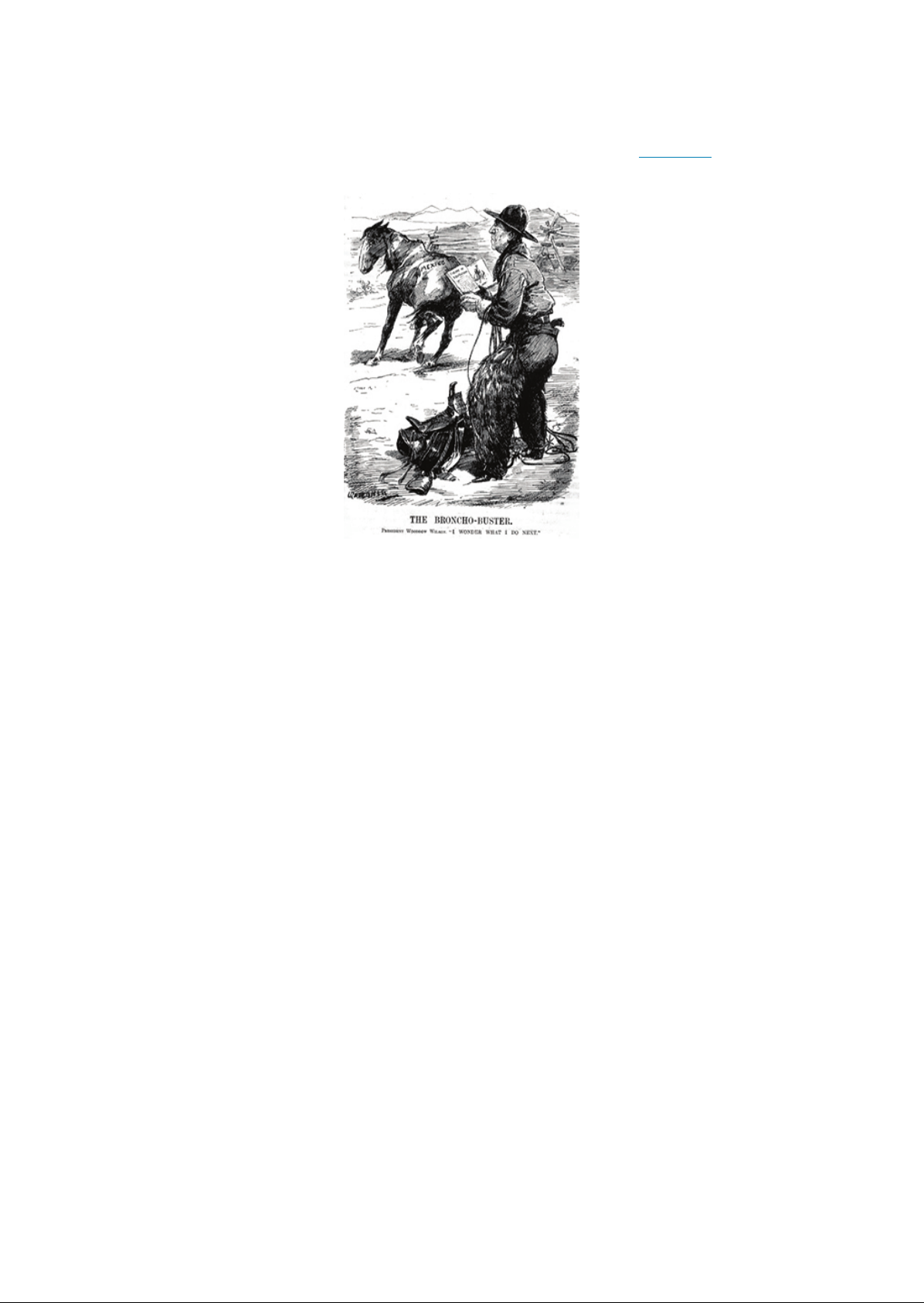

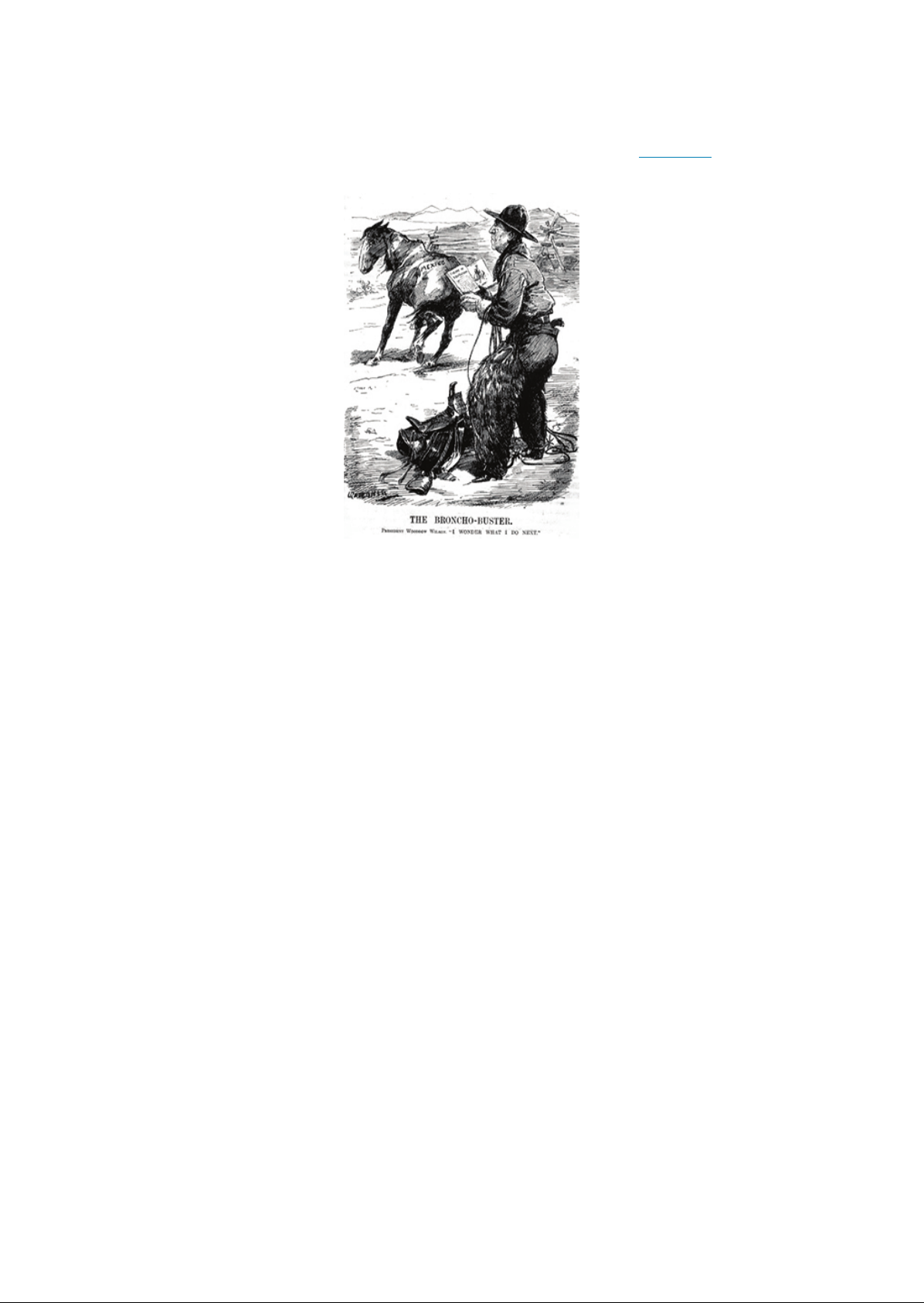

American and the European Origins of War during the Panamanian Revolution , and worked to establish effective in the Philippines in preparation for the eventual American withdrawal . Even with Bryan support , however , Wilson found that it was much harder than he anticipated to keep the United States out of world affairs ( Figure . In reality , the United States was interventionist in areas where its or threatened . FIGURE While Wilson strove to be less of an interventionist , he found that to be more in practice than in theory . Here , a political cartoon depicts him as a rather hapless cowboy , unclear on how to harness a foreign challenge , in this case , Mexico . Wilson greatest break from his predecessors occurred in Asia , where he abandoned Taft dollar diplomacy , a foreign policy that essentially used the power of economic dominance as a threat to gain favorable terms . Instead , Wilson revived diplomatic efforts to keep Japanese interference there at a minimum . But as World War I , also known as the Great War , began to unfold , and European nations largely abandoned their imperialistic interests in order to marshal their forces for , Japan demanded that China succumb to a Japanese protectorate over their entire nation . In 1917 , William Jennings Bryan successor as Secretary of State , Robert Lansing , signed the Agreement , which recognized Japanese control over the Manchurian region of China in exchange for Japan promise not to exploit the war to gain a greater foothold in the rest of the country . Furthering his goal of reducing overseas interventions , Wilson had promised not to rely on the Roosevelt Corollary , Theodore Roosevelt explicit policy that the United States could involve itself in Latin American politics whenever it felt that the countries in the Western Hemisphere needed policing . Once president , however , Wilson again found that it was more to avoid American interventionism in practice than in rhetoric . Indeed , Wilson intervened more in Western Hemisphere affairs than either Taft or Roosevelt . In 1915 , when a revolution in Haiti resulted in the murder of the Haitian president and threatened the safety of New York banking interests in the country , Wilson sent over three hundred Marines to establish order . Subsequently , the United States assumed control over the island foreign policy as well as its administration . One year later , in 1916 , Wilson again sent marines to , this time to the Dominican Republic , to ensure prompt payment of a debt that nation owed . In 1917 , Wilson sent troops to Cuba to protect sugar plantations from attacks by Cuban rebels this time , the troops remained for four years . Wilson most noted foreign policy foray prior to World War I focused on Mexico , where rebel general had seized control from a previous rebel government just weeks before inauguration . Wilson refused to recognize government , instead choosing to make an example of Mexico by demanding that they hold democratic elections and establish laws based on the moral principles he 607

608 23 Americans and the Great War , espoused . Wilson supported , who opposed military control of the country . When American intelligence learned of a German ship allegedly preparing to deliver weapons to forces , Wilson ordered the Navy to land forces at to stop the shipment . On April 22 , 1914 , a erupted between the Navy and Mexican troops , resulting in nearly 150 deaths , nineteen of them American . Although faction managed to overthrow in the summer of 1914 , most come to resent American intervention in their affairs . refused to work with Wilson and the government , and instead threatened to defend Mexico mineral rights against all American oil companies established there . Wilson then turned to support rebel forces who opposed , most notably Pancho Villa ( Figure . However , Villa lacked the strength in number or weapons to overtake in 1915 , Wilson reluctantly authorized recognition of government . FIGURE Pancho Villa , a Mexican rebel who Wilson supported , then from , attempted an attack on the United States in retaliation . Wilson actions in Mexico were emblematic of how it was to truly set the United States on a course of moral leadership . As a postscript , an irate Pancho Villa turned against Wilson , and on March , 1916 , led a force across the border into New Mexico , where they attacked and burned the town of Columbus . Over one hundred people died in the attack , seventeen of them American . Wilson responded by sending General John Pershing into Mexico to capture Villa and return him to the United States for trial . With over eleven thousand troops at his disposal , Pershing marched three hundred miles into Mexico before an angry ordered troops to withdraw from the nation . Although reelected in 1916 , Wilson reluctantly ordered the withdrawal of troops from Mexico in 1917 , avoiding war with Mexico and enabling preparations for American intervention in Europe . Again , as in China , Wilson attempt to impose a moral foreign policy had failed in light of economic and political realities . WAR ERUPTS IN EUROPE When a Serbian nationalist murdered the Archduke Franz Ferdinand of the Empire on June 28 , 1914 , the underlying forces that led to World War I had already long been in motion and seemed , at , to have little to do with the United States . At the time , the events that pushed Europe from ongoing tensions into war seemed very far away from interests . For nearly a century , nations had negotiated a series of mutual defense alliance treaties to secure themselves against their imperialistic rivals . Among the largest European powers , the Triple Entente included an alliance of France , Great Britain , and Russia . Opposite them , the Central powers , also known as the Triple Alliance , included Germany , the Ottoman Empire , and initially Italy . A series of side treaties likewise entangled the larger European powers to protect several smaller ones should war break out . At the same time that European nations committed each other to defense pacts , they jockeyed for power over empires overseas and invested heavily in large , modern militaries . Dreams of empire and military supremacy Access for free at .

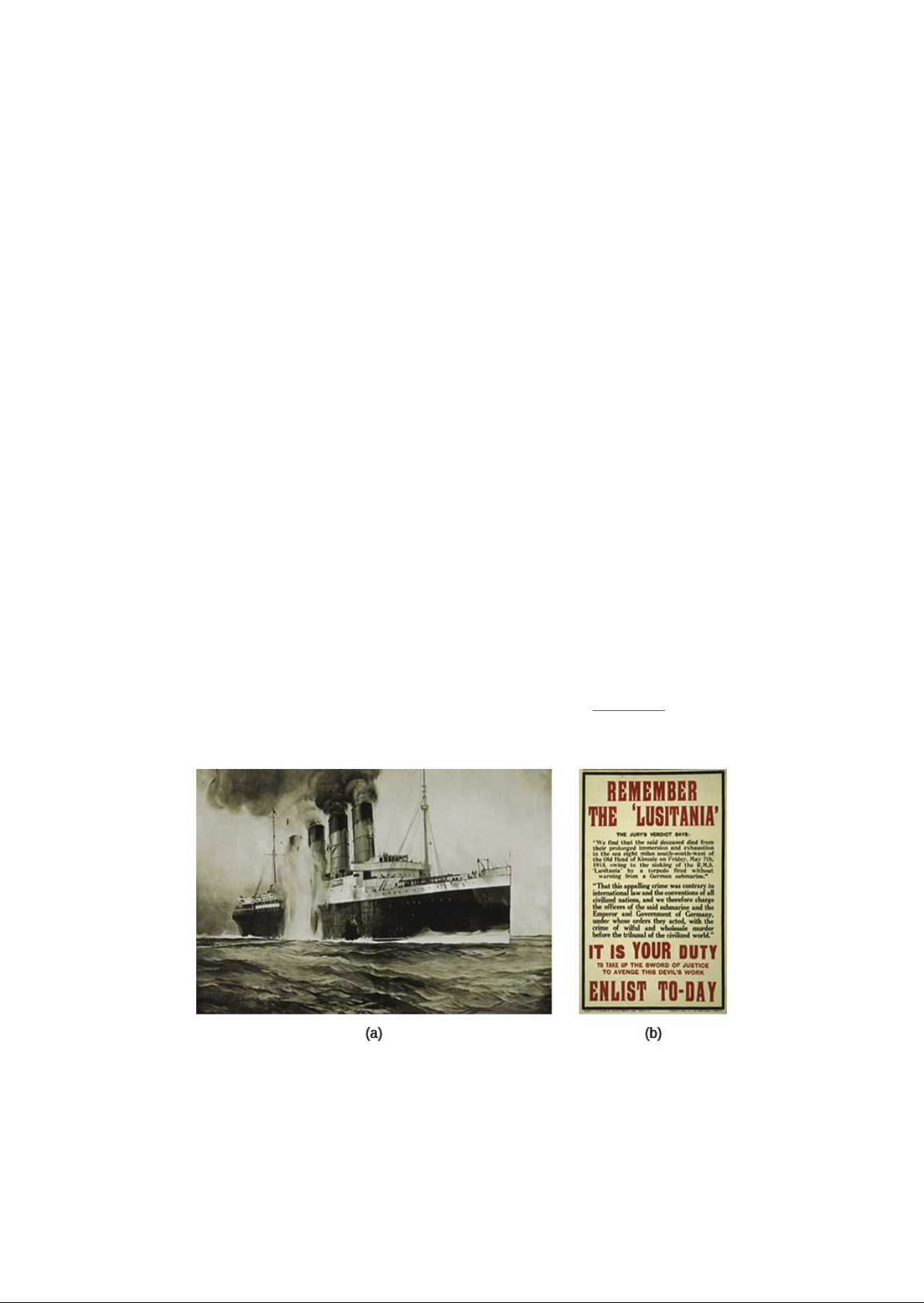

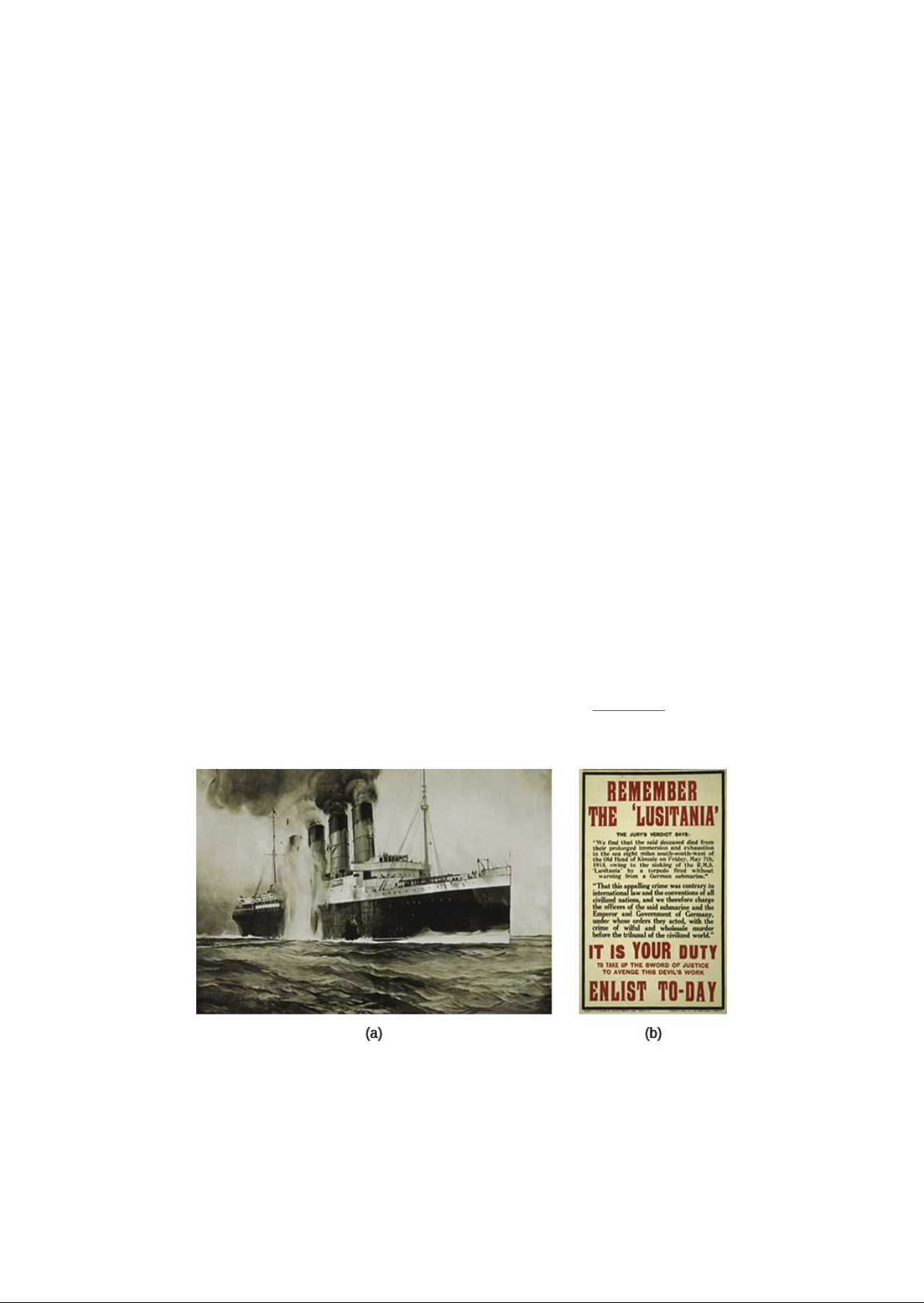

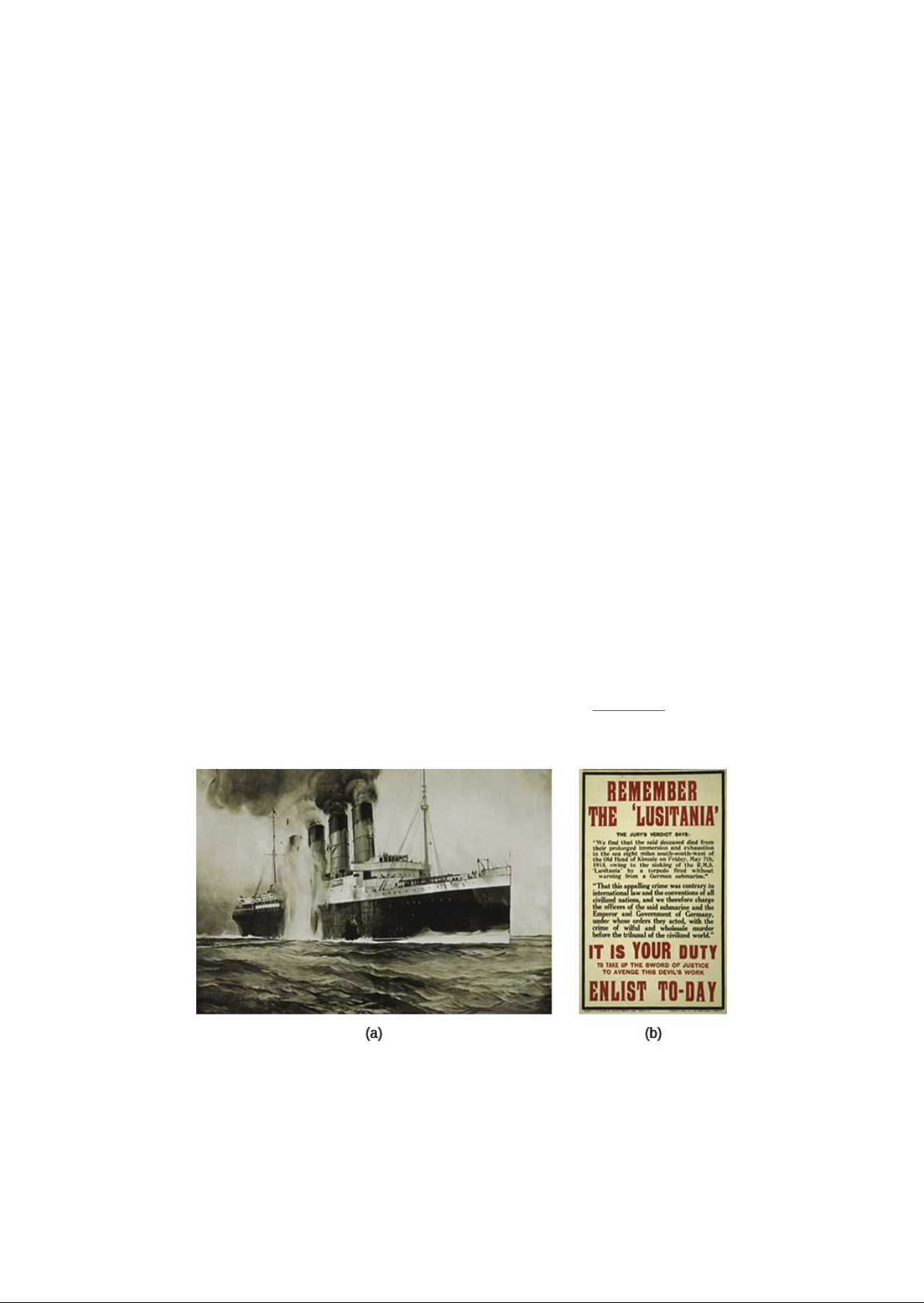

American and the European Origins of War 609 fueled an era of nationalism that was particularly pronounced in the newer nations of Germany and Italy , but also provoked separatist movements among Europeans . The Irish rose up in rebellion against British rule , for example . And in Bosnia capital of Sarajevo , Princip and his accomplices assassinated the Hungarian archduke in their for a nation . Thus , when Serbia failed to accede to Hungarian demands in the wake of the archduke murder , declared war on Serbia with the that it had the backing of Germany . This action , in turn , brought Russia into the , due to a reaty in which they had agreed to defend Serbia . Germany followed suit by declaring war on Russia , fearing hat Russia and France would seize this opportunity to move on Germany if it did not take the offensive . The eventual German invasion of Belgium drew Great Britain into the war , followed by the attack of the Ottoman Empire on Russia . By the end ofAugust 1914 , it seemed as if Europe had dragged the entire world into war . he Great War was unlike any war that came before it . Whereas in previous European , troops faced each other on open , World War I saw new military technologies that turned war into a of prolonged trench warfare . Both sides used new artillery , tanks , airplanes , machine guns , barbed wire , and , eventually , poison gas weapons that strengthened defenses and turned each military offense into of thousands of lives with minimal territorial advances in return . By the end of the war , he total military death toll was ten million , as well as another million civilian deaths attributed to military action , and another six million civilian deaths caused by famine , disease , or other related factors . One terrifying new piece of technological warfare was the German undersea boat or . By early 1915 , in an effort to break the British naval blockade of Germany and turn the tide of the war , the Germans dispatched a of these submarines around Great Britain to attack both merchant and military ships . The acted in direct violation of international law , attacking without warning from beneath the water instead of surfacing and permitting the surrender of civilians or crew . By 1918 , German had sunk nearly thousand vessels . Of greatest historical note was the attack on the British passenger ship , on its way from New York to Liverpool on May , 1915 . The German Embassy in the United States had announced that this ship would be subject to attack for its cargo of ammunition an allegation that later proved accurate . Nonetheless , almost civilians died in the attack , including 128 Americans . The attack the world , galvanizing support in England and beyond for the war Figure . This attack , more than any other event , would test President Wilson desire to stay out of what had been a largely European . FIGURE The torpedoing and sinking of the , depicted in the English drawing above ( a ) resulted in the death over twelve hundred civilians and was an international incident that shifted American sentiment as to their potential role in the war , as illustrated in a British recruiting poster ( THE CHALLENGE OF NEUTRALITY Despite the loss of American lives on the , President Wilson stuck to his path of neutrality in Europe

610 23 Americans and the Great War , escalating war in part out of moral principle , in part as a matter of practical necessity , and in part for political reasons . Few Americans wished to participate in the devastating battles that ravaged Europe , and Wilson did not want to risk losing his reelection by ordering an unpopular military intervention . Wilson neutrality did not mean isolation from all warring factions , but rather open markets for the United States and continued commercial ties with all belligerents . For Wilson , the did not reach the threshold of a moral imperative for involvement it was largely a European affair involving numerous countries with whom the United States wished to maintain working relations . In his message to Congress in 1914 , the president noted that Every man who really loves America will act and speak in the true spirit of neutrality , which is the spirit of impartiality and fairness and friendliness to all concerned . Wilson understood that he was already looking at a reelection bid . He had only won the 1912 election with 42 percent of the popular vote , and likely would not have been elected at all had Roosevelt not come back as a candidate to run against his former Taft . Wilson felt pressure from all different political constituents to take a position on the war , yet he knew that elections were seldom won with a campaign promise of If elected , I will send your sons to war ! Facing pressure from some businessmen and other government who felt that the protection of America best interests required a stronger position in defense of the Allied forces , Wilson agreed to a preparedness campaign in the year prior to the election . This campaign included the passage of the National Defense Act of 1916 , which more than doubled the size of the army to nearly , and the Naval Appropriations Act of 1916 , which called for the expansion of the , including battleships , destroyers , submarines , and other ships . As the 1916 election approached , the Republican Party hoped to capitalize on the fact that Wilson was making promises that he would not be able to keep . They nominated Charles Evans Hughes , a former governor of New York and sitting Supreme Court justice at the time of his nomination . Hughes focused his campaign on what he considered Wilson foreign policy failures , but even as he did so , he himself tried to walk a line between neutrality and belligerence , depending on his audience . In contrast , Wilson and the Democrats capitalized on neutrality and campaigned under the slogan kept us out of war . The election itself remained too close to call on election night . Only when a tight race in California was decided two days later could Wilson claim victory in his reelection bid , again with less than 50 percent of the popular vote . Despite his victory based upon a policy of neutrality , Wilson would true neutrality a challenge . Several different factors pushed Wilson , however reluctantly , toward the inevitability of American involvement . A key factor driving engagement was economics . Great Britain was the country most important trading partner , and the Allies as a whole relied heavily on American imports from the earliest days of the war forward . the value of all exports to the Allies quadrupled from 750 million to billion in the two years of the war . At the same time , the British naval blockade meant that exports to Germany all but ended , dropping from 350 million to 30 million . Likewise , numerous private banks in the United States made extensive excess of 500 England . Morgan banking interests were among the largest lenders , due to his family connection to the country . Another key factor complicating the decision to go to war was the deep ethnic divisions between Americans and more recent immigrants . For those of descent , the nations historic and ongoing relationship with Great Britain was paramount , but many resented British rule over their place of birth and opposed support for the world most expansive empire . Millions of Jewish immigrants had pogroms in Tsarist Russia and would have supported any nation that authoritarian state . German Americans saw their nation of origin as a victim of British and Russian aggression and a French desire to settle old scores , whereas emigrants from and the Ottoman Empire were mixed in their sympathies for the old monarchies or ethnic communities that these empires suppressed . For interventionists , this lack of support for Great Britain and its allies among recent immigrants only strengthened their conviction . Germany use of submarine warfare also played a role in challenging neutrality . After the sinking of the Access for free at .

American Isolationism and the European Origins of War 611 , and the subsequent August 30 sinking of another British liner , the Arabic , Germany had promised to restrict their use of submarine warfare . they promised to surface and visually identify any ship before they , as well as permit civilians to evacuate targeted ships . Instead , in February 1917 , Germany their use of submarines in an effort to end the war quickly before Great Britain naval blockade starved them out of food and supplies . The German high command wanted to continue unrestricted warfare on all Atlantic , including unarmed American freighters , in order to devastate the British economy and secure a quick and decisive victory . Their goal to bring an end to the war before the United States could intervene and tip the balance in this grueling war of attrition . In February 1917 , a German sank the American merchant ship , the , killing two passengers , and , in late March , quickly sunk four more American ships . These attacks increased pressure on Wilson from all sides , as government , the general public , and both Democrats and Republicans urged him to declare war . The element that led to American involvement in World War I was the telegram . British intelligence intercepted and decoded a telegram from German foreign minister Arthur to the German ambassador to Mexico , instructing the latter to invite Mexico to join the war effort on the German side , should the United States declare war on Germany . It further went on to encourage Mexico to invade the United States if such a declaration came to pass , as Mexico invasion would create a diversion and permit Germany a clear path to victory . In exchange , offered to return to Mexico land that was previously lost to the United States in the War , including Arizona , New Mexico , and Texas ( Figure ) nu nuI ' FIGURE The Temptation , which appeared in the Dallas Morning News on March , 1917 , shows Germany as the Devil , tempting Mexico to join their war effort against the United States in exchange forthe return of land formerly Mexico . The prospect of such a move made it all but impossible for Wilson to avoid war . credit Library of Congress ) The likelihood that Mexico , weakened and torn by its own revolution and civil war , could wage war against the United States and recover territory lost in the war with Germany help was remote at best . But combined with Germany unrestricted use of submarine warfare and the sinking of American ships , the telegram made a powerful argument for a declaration of war . The outbreak of the Russian Revolution in February and abdication of Tsar Nicholas II in March raised the prospect of democracy in the Eurasian empire and removed an important moral objection to entering the war on the side of the Allies . On April , 1917 , Wilson asked Congress to declare war on Germany . Congress debated for four days , and several senators and congressmen expressed their concerns that the war was being fought over economic interests more than strategic need or democratic ideals . When Congress voted on April , voted against the resolution , including the woman ever elected to Congress , Representative Rankin . This was the largest no vote against a war resolution in American history .

612 23 Americans and the Great War , DEFINING AMERICAN Wilson Peace without Victory Speech Wilson effort to avoid bringing the United States into World is captured in a speech he gave before the Senate on January 22 , 1917 . This speech , known as the Peace without Victory speech , extolled the country to be patient , as the countries involved in the war were nearing a peace . Wilson stated It must be a peace without victory . It is not pleasant to say this . I beg that I may be permitted to put my own interpretation upon it and that it may be understood that no other interpretation was in my thought . I am seeking only to face realities and to face them without soft . Victory would mean peace forced upon the loser , a victor terms imposed upon the vanquished . It would be accepted in humiliation , under duress , at an intolerable , and would leave a sting , a resentment , a bitter memory upon which terms of peace would rest , not permanently , but only as upon quicksand . Only a peace between equals can last , only a peace the very principle of which is equality and a common participation in a common benefit . Not surprisingly , this speech was not well received by either side the war . England resisted being put on the same moral ground as Germany , and France , whose country had been battered by years of warfare , had no desire to end the war without victory and its spoils . Still , the speech as a whole illustrates Wilson idealistic , if failed , attempt to create a more benign and foreign policy role for the United States . Unfortunately , the telegram and the sinking of the American merchant ships proved too provocative for Wilson to remain neutral . Little more than two months speech , he asked Congress to declare war on Germany . CLICK AND EXPLORE Read the full transcript ofthe Peace without Victory speech ( that clearly shows Wilson desire to remain out of the war , even when it seemed inevitable . The United States Prepares for War LEARNING OBJECTIVES By the end ofthis section , you will be able to steps taken by the government to secure enough men , money , food , and supplies to prosecute World Warl Explain how the government attempted to sway popular opinion in favor ofthe war effort Wilson knew that the key to America success in war lay largely in its preparation . With both the Allied and enemy forces entrenched in battles of attrition , and supplies running low on both sides , the United States needed , and foremost , to secure enough men , money , food , and supplies to be successful . The country needed to supply the basic requirements to a war , and then work to ensure military leadership , public support , and strategic planning . THE INGREDIENTS OF WAR The First World War was , in many ways , a war of attrition , and the United States needed a large army to help the Allies . In 1917 , when the United States declared war on Germany , the Army ranked seventh in the world in terms of size , with an estimated enlisted men . In contrast , at the outset of the war in 1914 , the German force included million men , and the country ultimately mobilized over eleven million soldiers over the course of the entire war . To compose a force , Congress passed the Selective Service Act in 1917 , which initially required all men aged through thirty to register for the draft Figure . In 1918 , the act was expanded to include all men between eighteen and . Through a campaign of patriotic appeals , as well as an Access for free at .

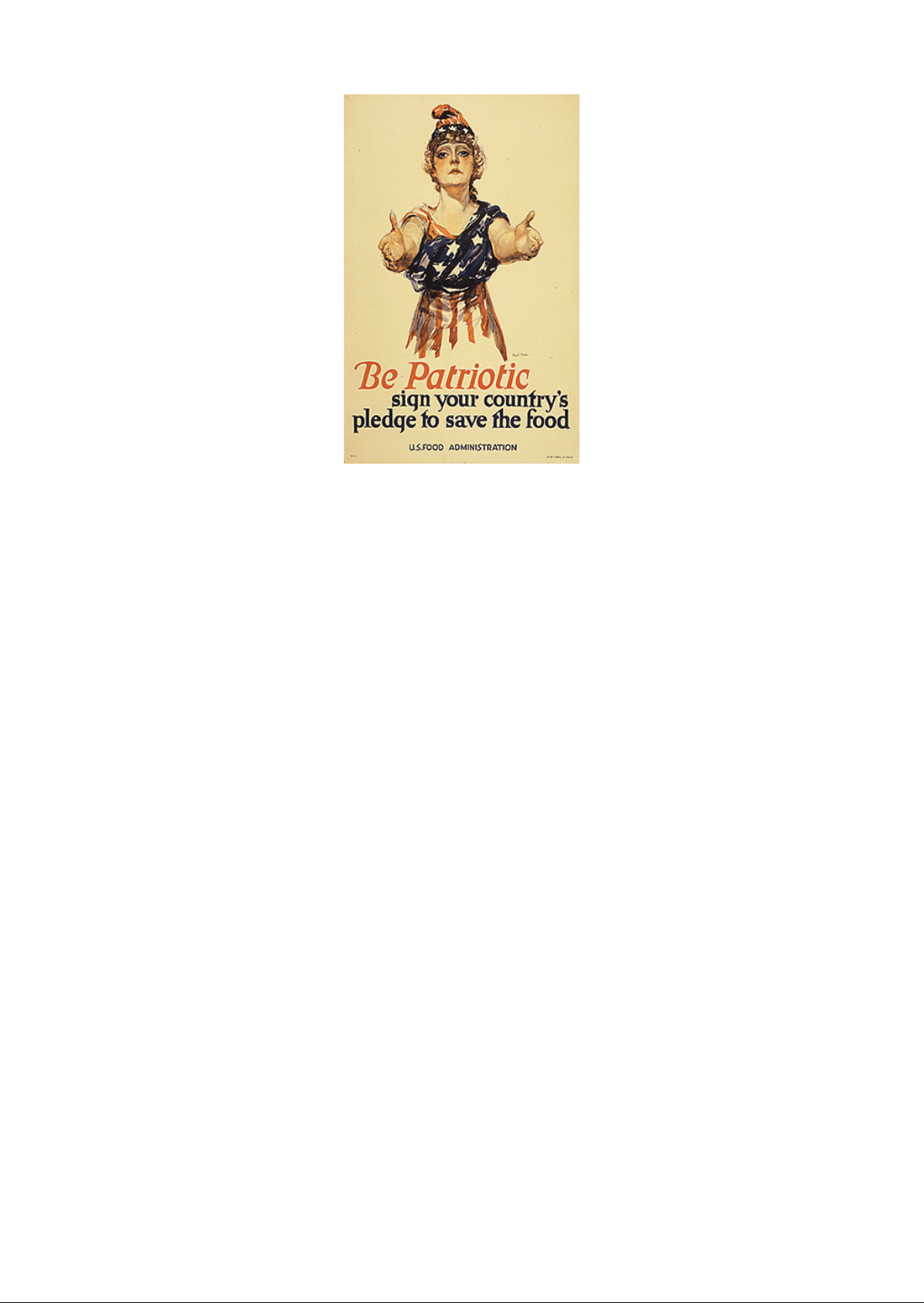

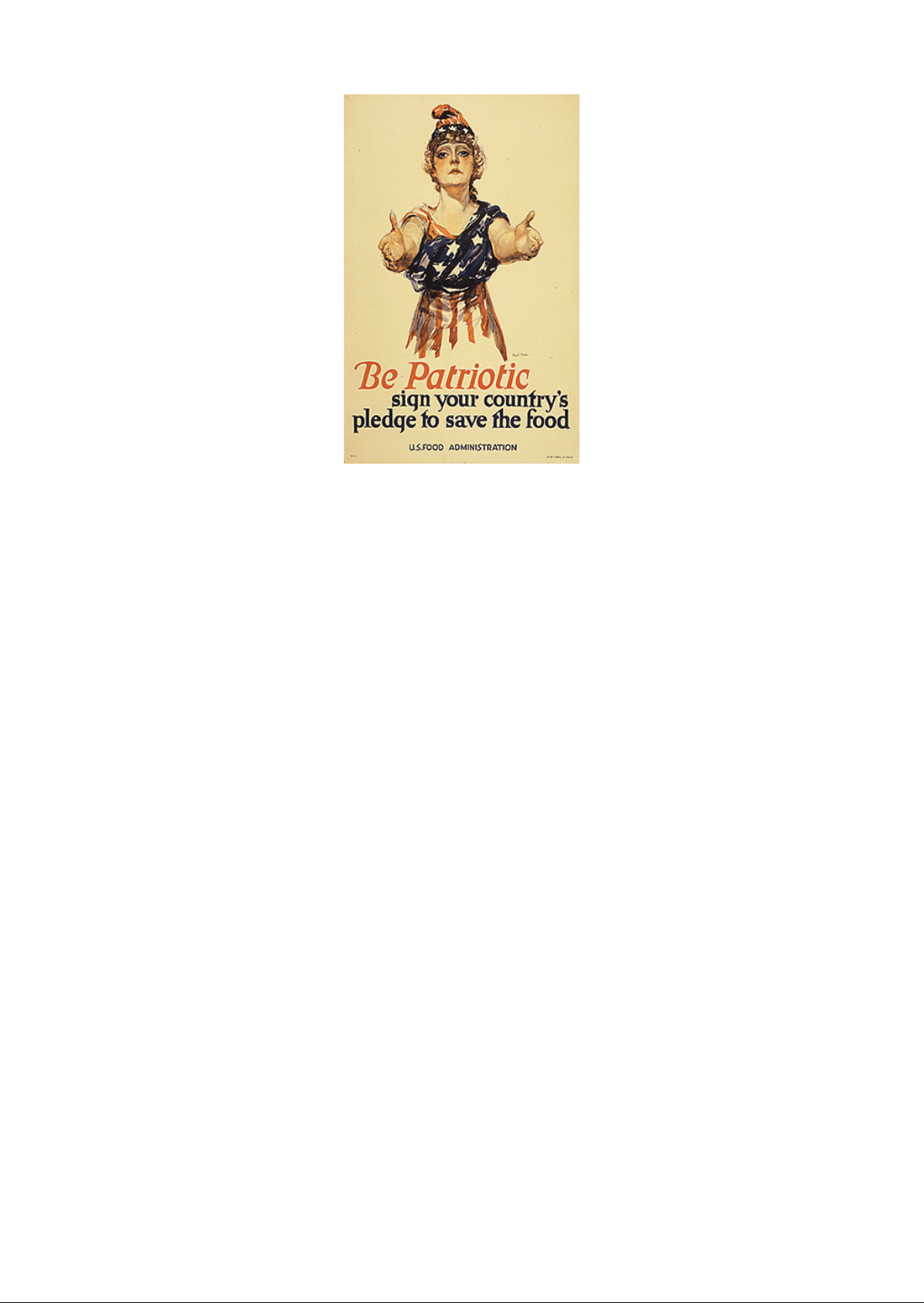

The United States Prepares for War administrative system that allowed men to register at their local draft boards rather than directly with the federal government , over ten million men registered for the draft on the very day . By the war end , million men had registered for the Army draft . Five million of these men were actually drafted , another million volunteered , and over additional men signed up for the navy or marines . In all , two million men participated in combat operations overseas . Among the volunteers were also twenty thousand women , a quarter of whom went to France to serve as nurses or in clerical positions . But the draft also provoked opposition , and almost eligible Americans refused to register for military service . About of these the conscription law as conscientious objectors , mostly on the grounds of their deeply held religious beliefs . Such opposition was not without risks , and whereas most objectors were never prosecuted , those who were found guilty at military hearings received stiff punishments Courts handed down over two hundred prison sentences of twenty years or more , and seventeen death sentences . FIGURE While many young men were eager to join the war effort , there were a sizable number who did not want to join , either due to a moral objection or simply because they did not want to in a war that seemed far from American interests . credit Library of Congress ) With the size of the army growing , the government next needed to ensure that there were adequate particular food and both the soldiers and the home front . Concerns over shortages led to the passage of the Lever Food and Fuel Control Act , which empowered the president to control the production , distribution , and price of all food products during the war effort . Using this law , Wilson created both a Fuel Administration and a Food Administration . The Fuel Administration , run by Harry , created the concept of fuel holidays , encouraging civilian Americans to do their part for the war effort by rationing fuel on certain days . also implemented daylight saving time for the time in American history , shifting the clocks to allow more productive daylight hours . Herbert Hoover coordinated the Food Administration , and he too encouraged volunteer rationing by invoking patriotism . With the slogan food will win the war , Hoover encouraged Meatless Mondays , Wheatless Wednesdays , and other similar reductions , with the hope of rationing food for military use ( Figure )

614 23 Americans and the Great War , the ro ?

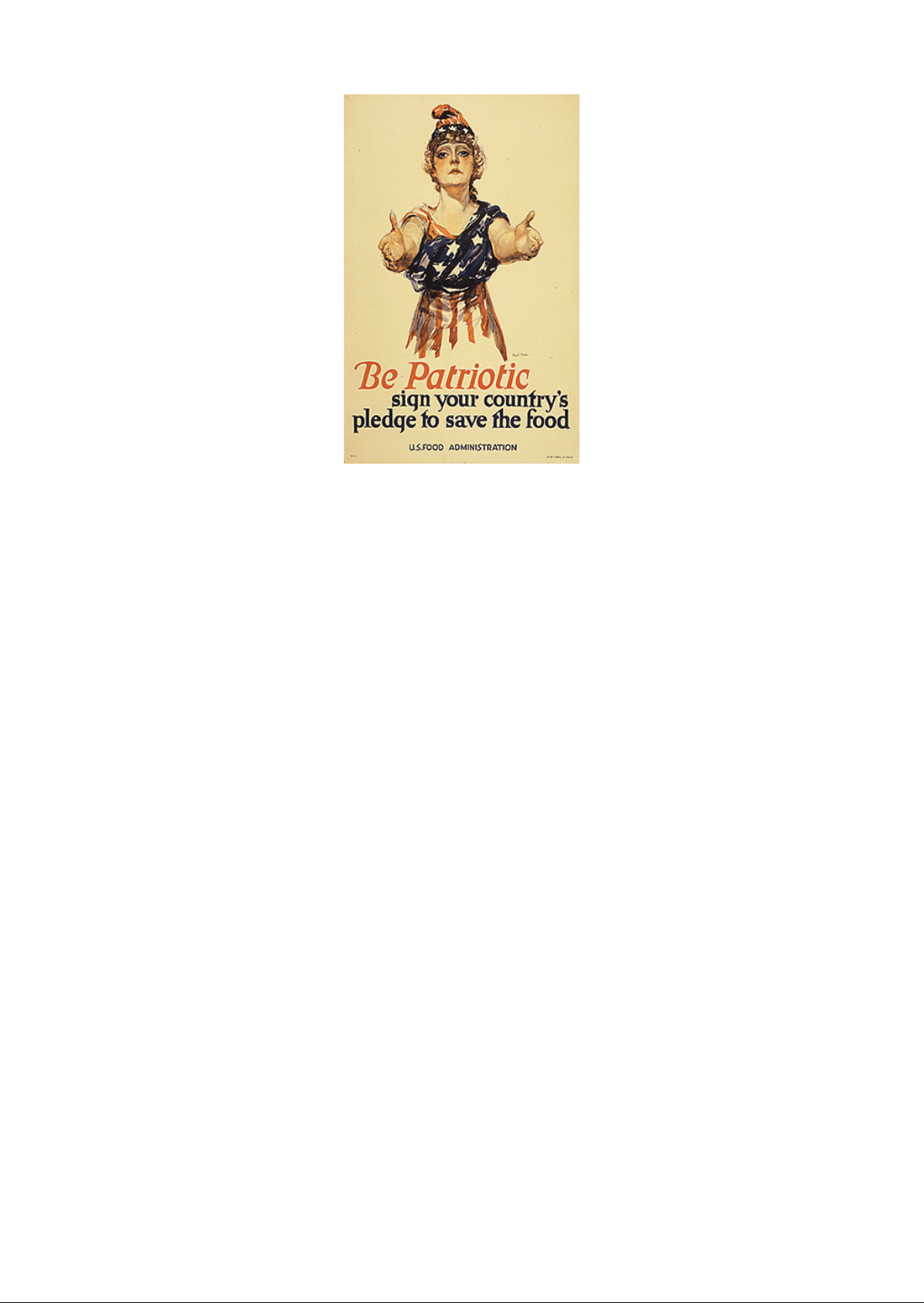

FIGURE With massive propaganda campaigns linking rationing and frugality to patriotism , the government sought to ensure adequate supplies to the war . Wilson also created the War Industries Board , run by Bernard Baruch , to ensure adequate military supplies . The War Industries Board had the power to direct shipments of raw materials , as well as to control government contracts with private producers . Baruch used lucrative contracts with guaranteed to encourage several private to shift their production over to wartime materials . For those that refused to cooperate , Baruch government control over raw materials provided him with the necessary leverage to convince them to join the war effort , willingly or not . As a way to move all the personnel and supplies around the country , Congress created the Railroad Administration . Logistical problems had led trains bound for the East Coast to get stranded as far away as Chicago . To prevent these problems , Wilson appointed William , the Secretary of the Treasury , to lead this agency , which had extraordinary war powers to control the entire railroad industry , including , terminals , rates , and wages . Almost all the practical steps were in place for the United States to a successful war . The only step remaining was to out how to pay for it . The war effort was an eventual price tag in excess of 32 billion by the government needed to it . The Liberty Loan Act allowed the federal government to sell liberty bonds to the American public , extolling citizens to do their part to help the war effort and bring the troops home . The government ultimately raised 23 billion through liberty bonds . Additional monies came from the government use of federal income tax revenue , which was made possible by the passage of the Sixteenth Amendment to the Constitution in 1913 . With the , transportation , equipment , food , and men in place , the United States was ready to enter the war . The next piece the country needed was public support . CONTROLLING DISSENT Although all the physical pieces required to a war fell quickly into place , the question of national unity was another concern . The American public was strongly divided on the subject of entering the war . While many felt it was the only choice , others protested strongly , feeling it was not America war to . Wilson needed to ensure that a nation of diverse immigrants , with ties to both sides of the , thought of themselves as American , and their home country nationality second . To do this , he initiated a propaganda campaign , pushing the America First message , which sought to convince Americans that they should do everything in their power to ensure an American victory , even if that meant silencing their own Access for free at .

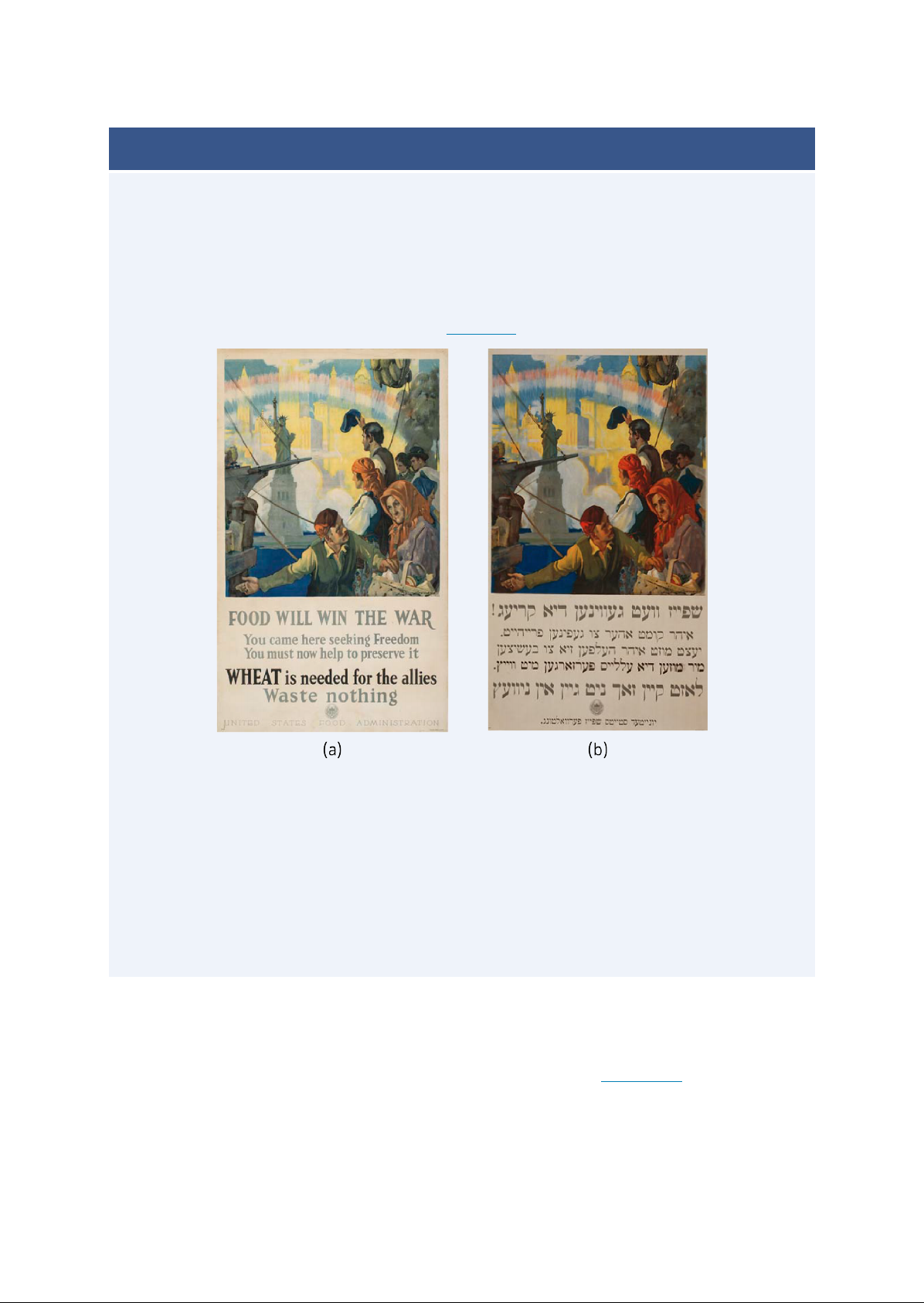

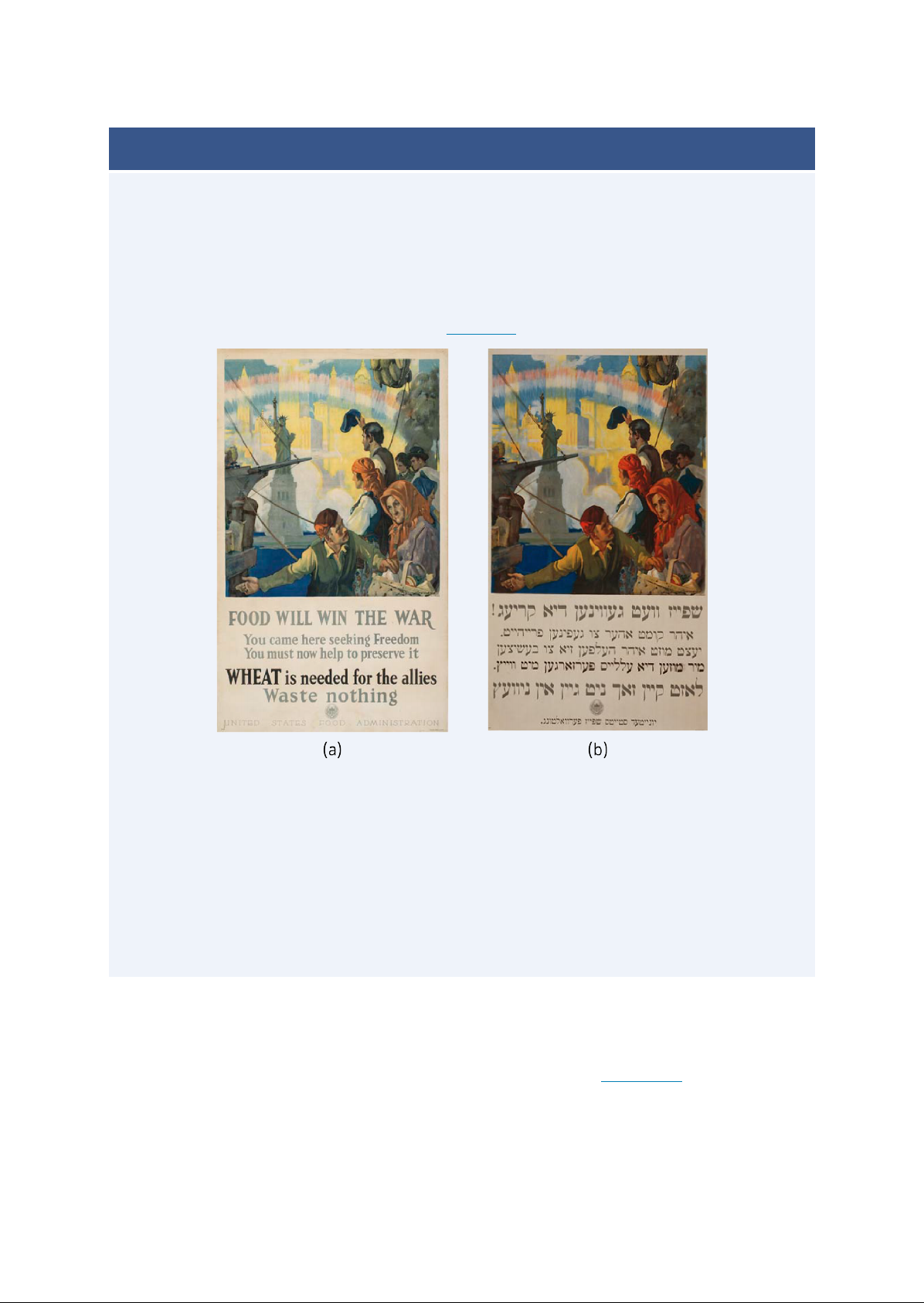

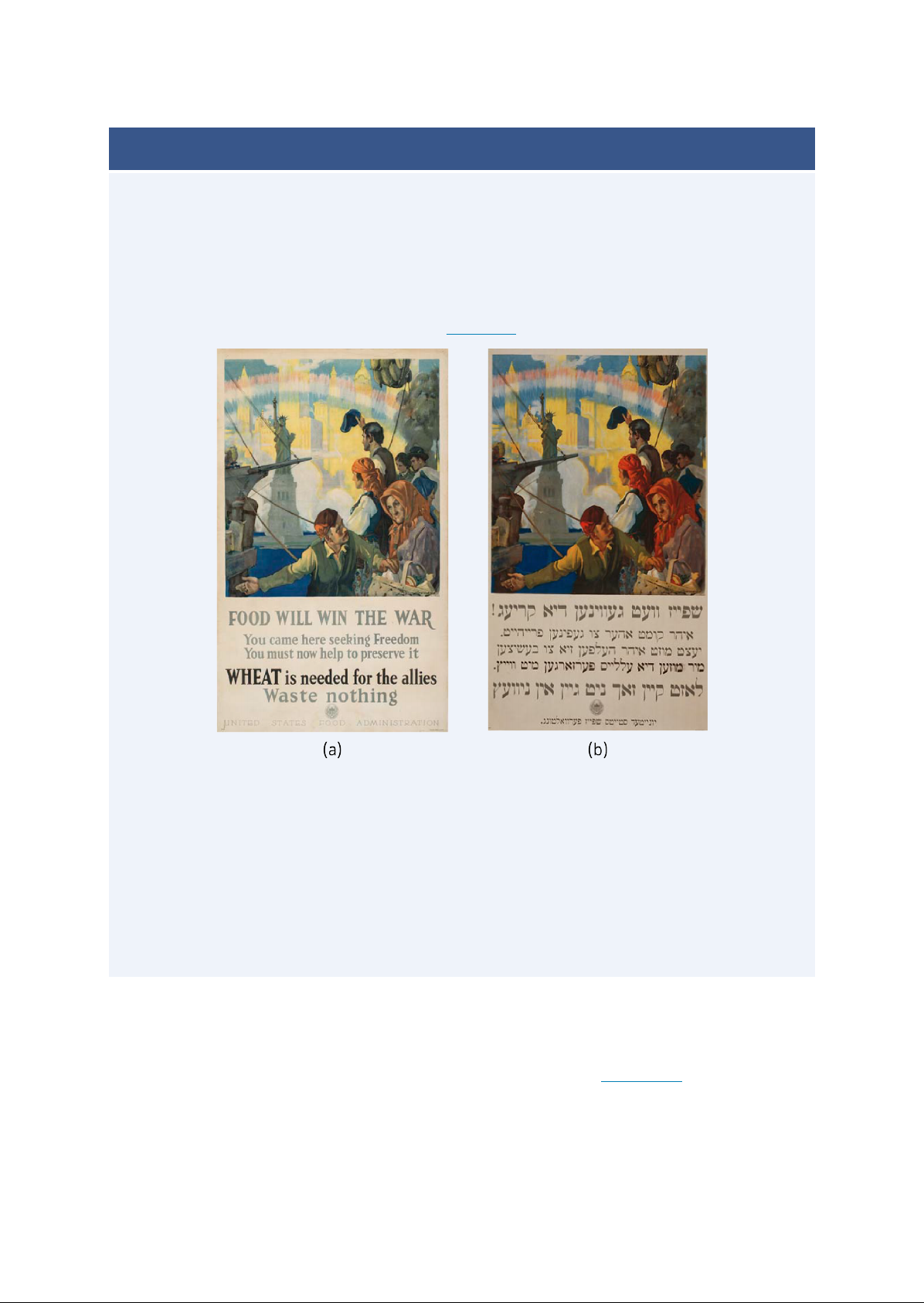

The United States Prepares for War criticisms . AMERICANA American First , American Above All At the outset of the war , one of the greatest challenges for Wilson was the lack of national unity . The country , after all , was made up of immigrants , some recently arrived and some well established , but all with ties to their home countries . These home countries included Germany and Russia , as well as Great Britain and France . In an effort to ensure that Americans eventually supported the war , the government propaganda campaign focused on driving home that message . The posters below , shown in both English and Yiddish , prompted immigrants to remember what they owed to America Figure . ram ' ix . romp array 15 ' min my um om rip . win roon WILL THE WAR You mine here seeking You must now to preserve it WHEAT is needed for the allies Waste nothing ( a ) FIGURE These posters clearly illustrate the pressure exerted on immigrants to quell any dissent they might feel about the United States at war . Regardless of how patriotic immigrants might feel and act , however , an xenophobia overtook the country . German Americans were persecuted and their businesses shunned , whether or not they voiced any objection to the war . Some cities changed the names of the streets and buildings if they were German . Libraries withdrew books from the shelves , and German Americans began to avoid speaking German for fear of reprisal . For some immigrants , the war was fought on two fronts on the of France and again at home . The Wilson administration created the Committee of Public Information under director George Creel , a former journalist , just days after the United States declared war on Germany . Creel employed artists , speakers , writers , and to develop a propaganda machine . The goal was to encourage all Americans to make during the war and , equally importantly , to hate all things German ( Figure 2310 . Through efforts such as the establishment of loyalty leagues in ethnic immigrant communities , Creel largely succeeded in molding an sentiment around the country . The result ?

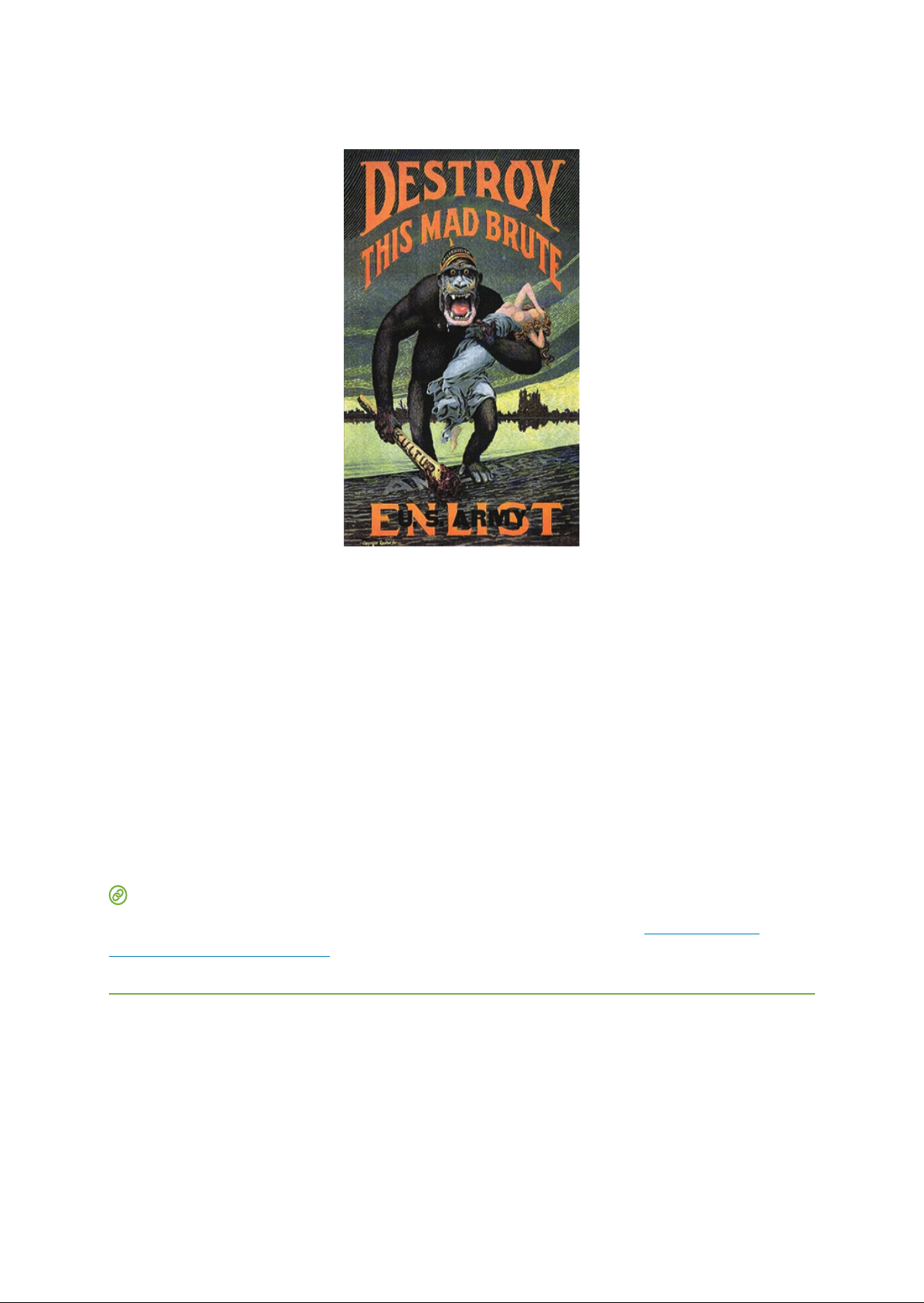

Some schools banned the teaching of the German language and some restaurants refused to serve frankfurters , sauerkraut , or hamburgers , instead serving liberty dogs with liberty cabbage and liberty Symphonies refused to perform music written by German composers . The hatred of Germans grew so widespread that , at one point , at a circus , 615

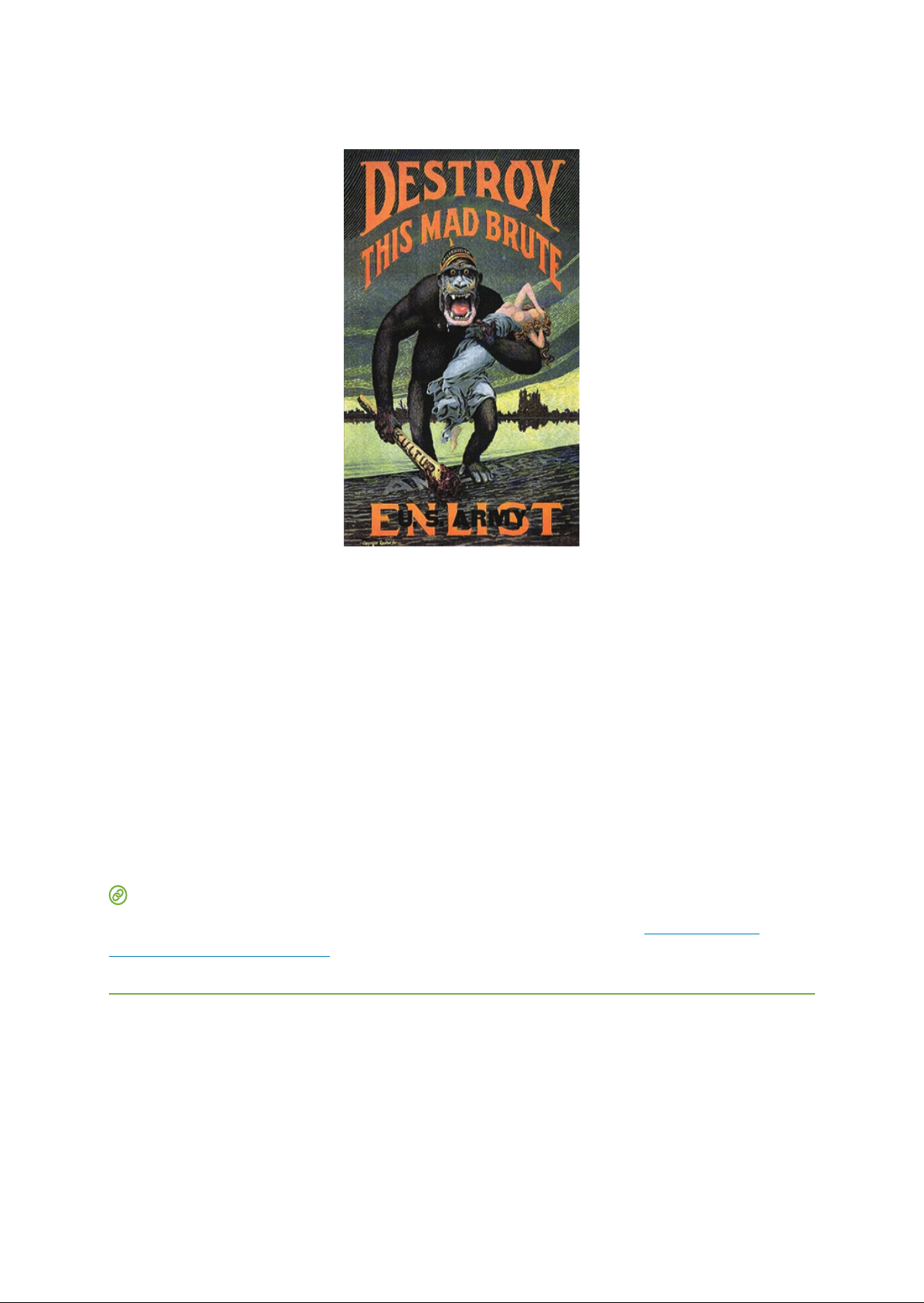

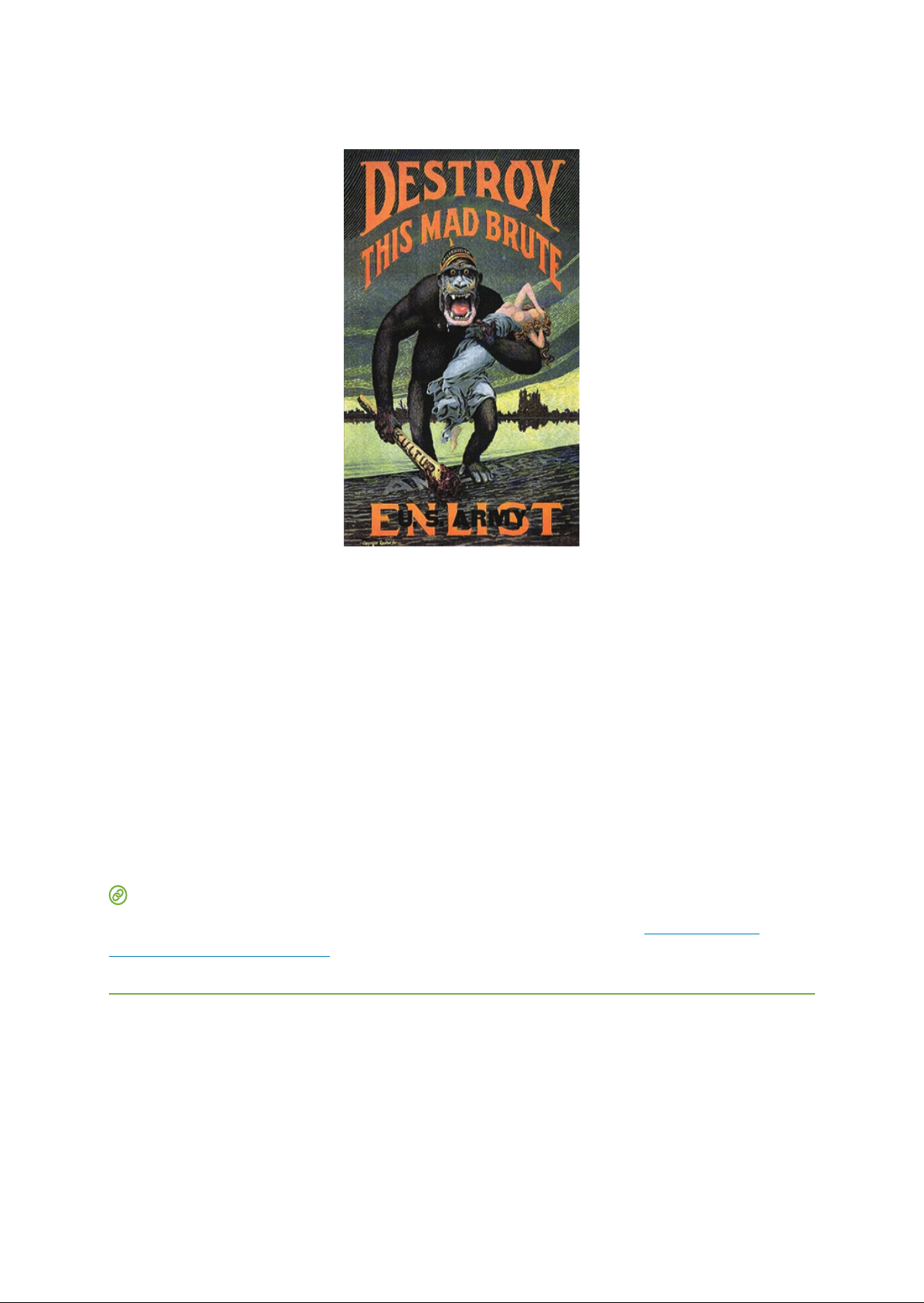

616 23 Americans and the Great War , audience members cheered when , in an act gone horribly wrong , a Russian bear mauled a German animal trainer ( whose ethnicity was more a part of the act than reality ) FIGURE Creel propaganda campaign embodied a strongly message . The depiction of Germans as brutal apes , stepping on the nation shores with their crude weapon of ( culture ) stood in marked contrast to the idealized rendition of the nation virtue as a fair beauty whose clothes had been ripped off her . In addition to its propaganda campaign , the government also tried to secure broad support for the war effort with repressive legislation . The Trading with the Enemy Act of 1917 prohibited individual trade with an enemy nation and banned the use of the postal service for disseminating any literature deemed treasonous by the postmaster general . That same year , the Espionage Act prohibited giving aid to the enemy by spying , or espionage , as well as any public comments that opposed the American war effort . Under this act , the government could impose and imprisonment of up to twenty years . The Sedition Act , passed in 1918 , prohibited any criticism or disloyal language against the federal government and its policies , the Constitution , the military uniform , or the American . More than two thousand persons were charged with violating these laws , and many received prison sentences of up to twenty years . Immigrants faced deportation as punishment for their dissent . Not since the Alien and Sedition Acts of 1798 had the federal government so infringed on the freedom of speech of loyal American citizens . CLICK AND EXPLORE For a sense of the response and pushback that antiwar sentiments incited , read this newspaper article from 1917 , discussing the dissemination of antidraft by the No Conscription League . In the months and years after these laws came into being , over one thousand people were convicted for their violation , primarily under the Espionage and Sedition Acts . More importantly , many more war critics were frightened into silence . One notable prosecution was that of Socialist Party leader Eugene Debs , who received a prison sentence for encouraging draft resistance , which , under the Espionage Act , was considered giving aid to the enemy . Prominent Socialist Victor Berger was also prosecuted under the Espionage Act and subsequently twice denied his seat in Congress , to which he had been properly elected by the citizens of Milwaukee , Wisconsin . One of the more outrageous prosecutions was that of a producer who released a about the American Revolution Prosecutors found the seditious , and a court convicted the producer Access for free at .

A New Home Front 617 to ten years in prison for portraying the British , who were now American allies , as the obedient soldiers of a monarchical empire . State and local , as well as private citizens , aided the government efforts to investigate , identify , and crush subversion . Over communities created local councils of defense , which encouraged members to report any antiwar comments to local authorities . This mandate encouraged spying on neighbors , teachers , local newspapers , and other individuals . In addition , a larger national American Protective support from the Department of Justice to spy on prominent dissenters , as well as open their mail and physically assault draft evaders . Understandably , opposition to such repression began mounting . In 1917 , Roger Baldwin formed the National Civil Liberties forerunner to the American Civil Liberties Union , which was founded in challenge the government policies against wartime dissent and conscientious objection . In 1919 , the case of United States went to the Supreme Court to challenge the constitutionality of the Espionage and Sedition Acts . The case concerned Charles , a leader in the Socialist Party of Philadelphia , who had distributed thousand leaflets , encouraging young men to avoid conscription . The court ruled that during a time of war , the federal government was in passing such laws to quiet dissenters . The decision was unanimous , and in the court opinion , Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes wrote that such dissent presented a clear and present danger to the safety of the United States and the military , and was therefore . He further explained how the First Amendment right of free speech did not protect such dissent , in the same manner that a citizen could not be freely permitted to yell ! in a crowded theater , due to the danger it presented . Congress ultimately repealed most of the Espionage and Sedition Acts in 1921 , and several who were imprisoned for violation of those acts were then quickly released . But the Supreme deference to the federal government restrictions on civil liberties remained a volatile topic in future wars . A New Home Front LEARNING OBJECTIVES By the end ofthis section , you will be able to Explain how the status of organized labor changed duringthe First World War Describe how the lives of women and African Americans changed as a result of American participation in World War I Explain how America participation in World allowed for the passage of prohibition and women suffrage The lives of all Americans , whether they went abroad to or stayed on the home front , changed dramatically during the war . Restrictive laws censored dissent at home , and the armed forces demanded unconditional loyalty from millions of volunteers and conscripted soldiers . For organized labor , women , and African Americans in particular , the war brought changes to the prewar status quo . Some White women worked outside of the home for the time , whereas others , like African American men , found that they were eligible for jobs that had previously been reserved for White men . African American women , too , were able to seek employment beyond the domestic servant jobs that had been their primary opportunity . These new options and freedoms were not easily erased after the war ended . NEW OPPORTUNITIES BORN FROM WAR After decades of limited involvement in the challenges between management and organized labor , the need for peaceful and productive industrial relations prompted the federal government during wartime to invite organized labor to the negotiating table . Samuel , head of the American Federation of Labor ( sought to capitalize on these circumstances to better organize workers and secure for them better wages and working conditions . His efforts also his own base of power . The increase in production that the war required exposed severe labor shortages in many states , a condition that was further exacerbated by the draft , which pulled millions of young men from the active labor force . Wilson only investigated the longstanding animosity between labor and management before ordering

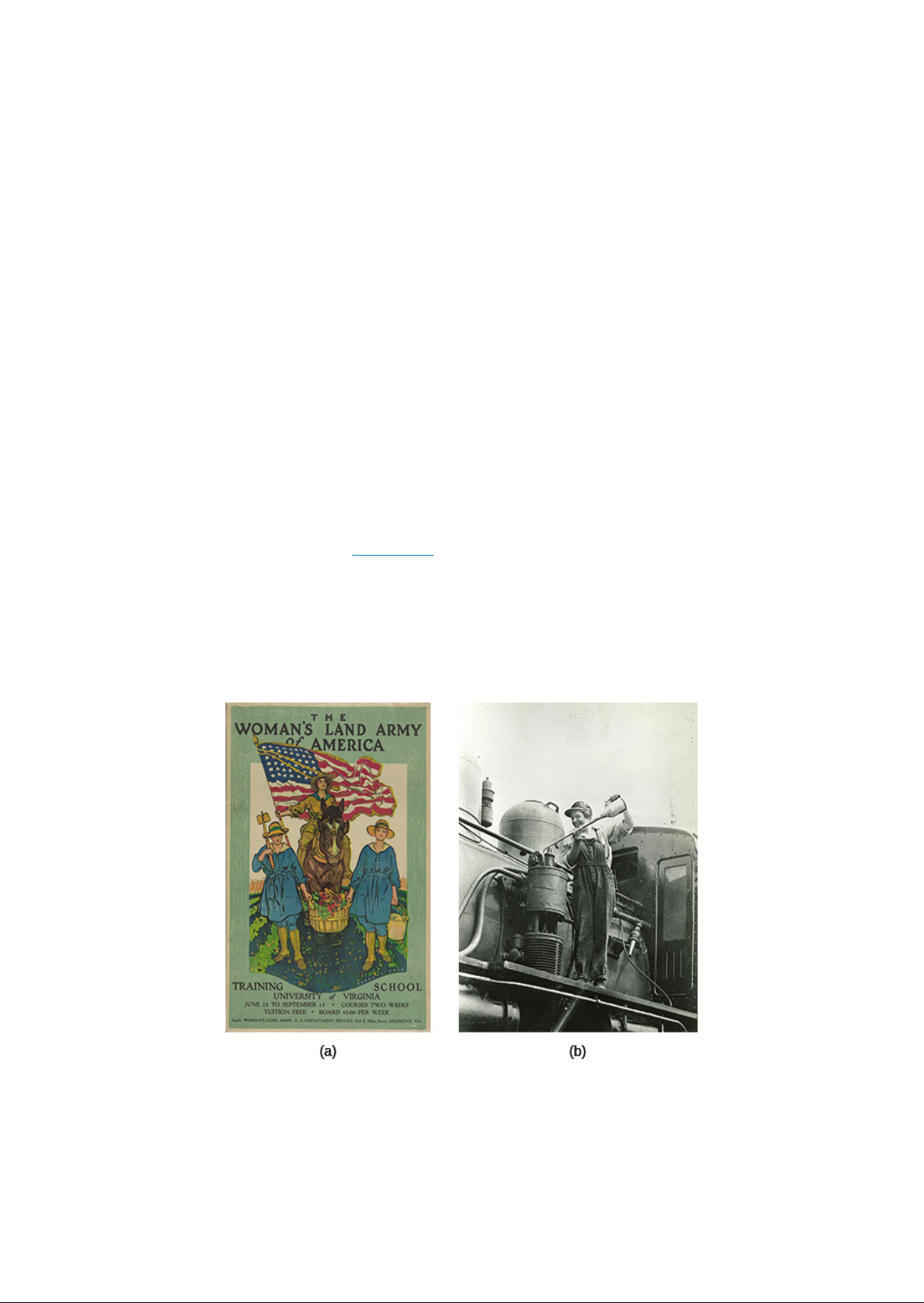

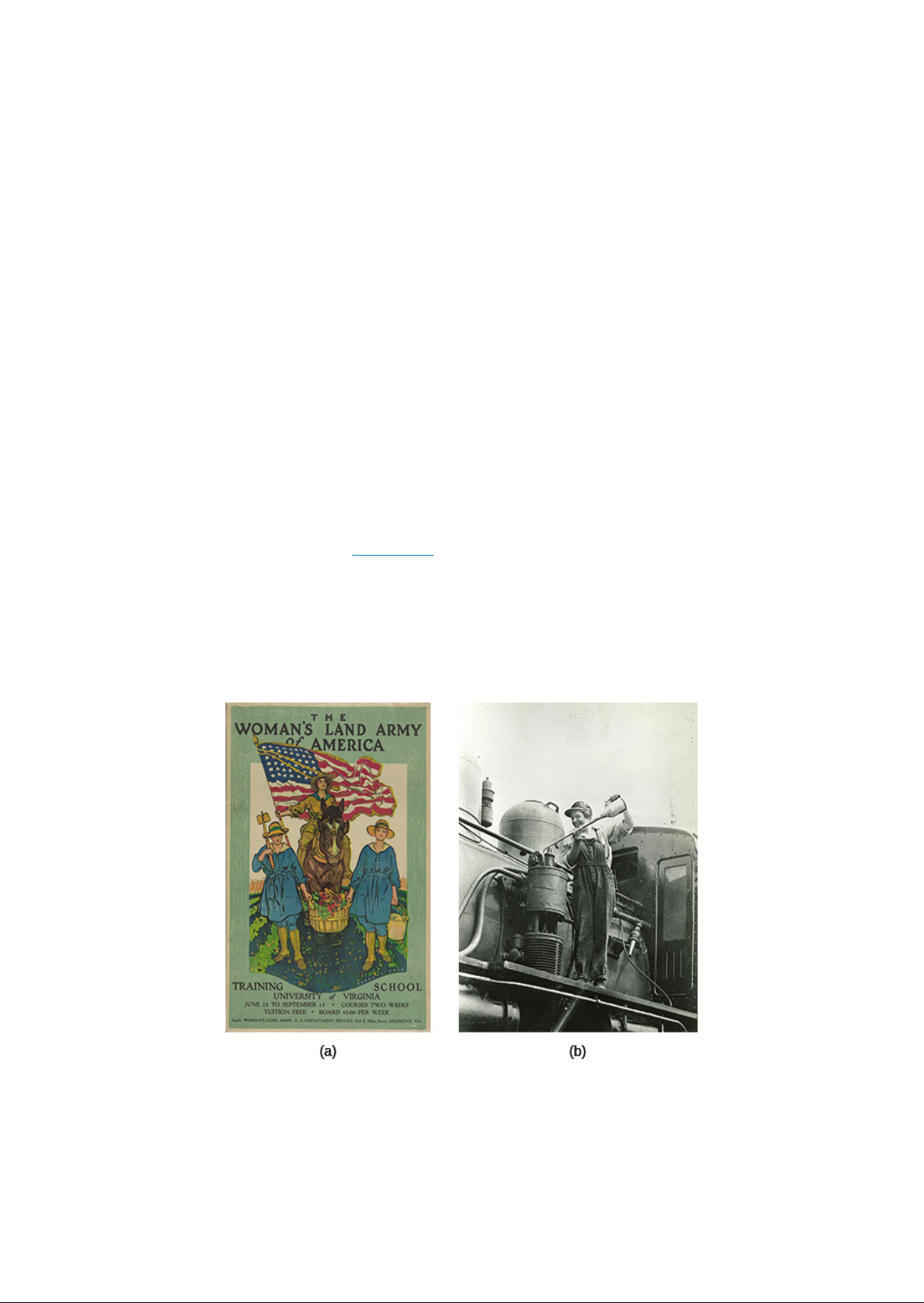

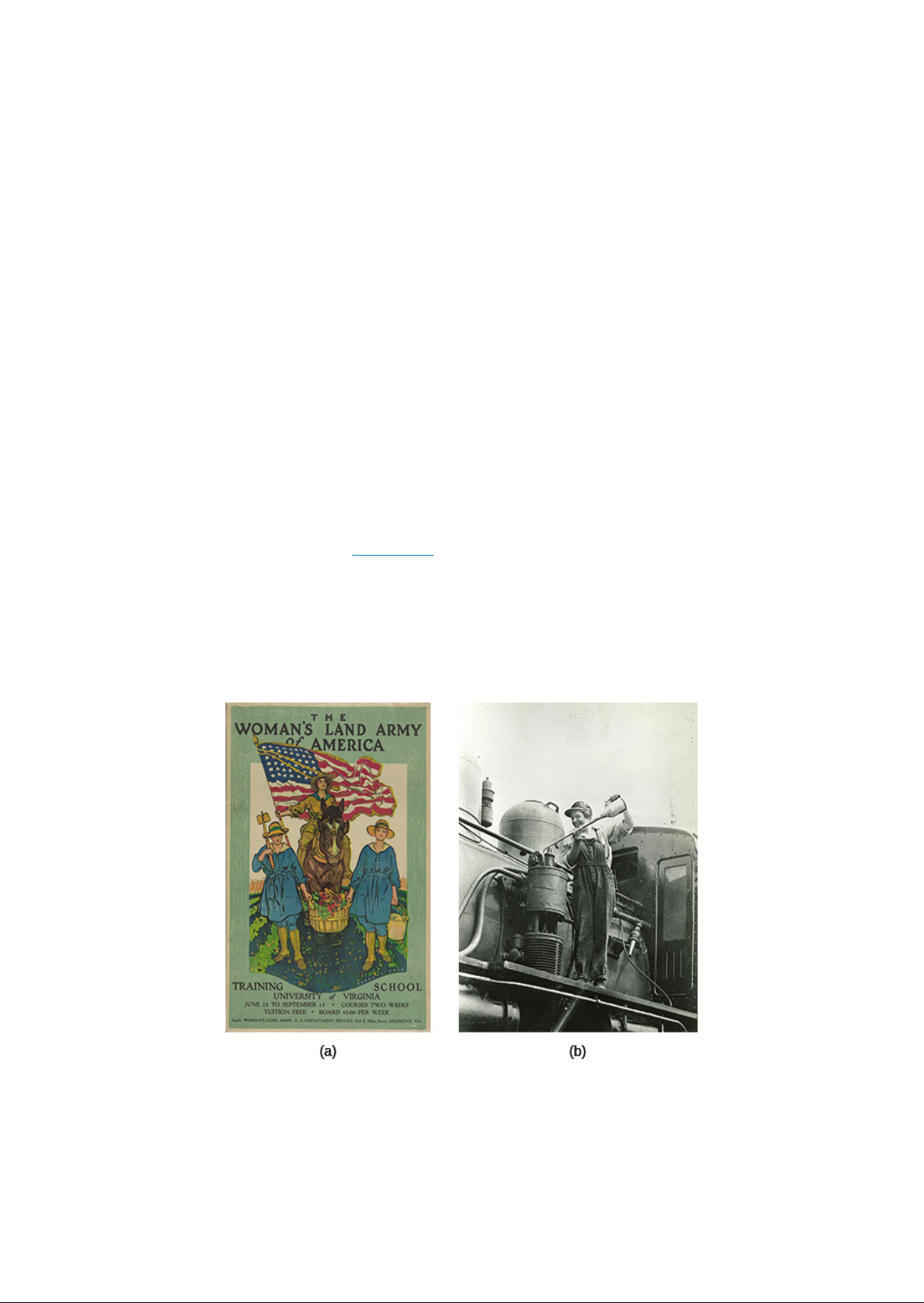

618 23 Americans and the Great War , the creation of the National Labor War Board in April 1918 . Quick negotiations with and the resulted in a promise Organized labor would make a pledge for the duration of the war , in exchange for the government protection of workers rights to organize and bargain collectively . The federal government kept its promise and promoted the adoption of an workday ( which had been adopted by government employees in 1868 ) a living wage for all workers , and union membership . As a result , union membership skyrocketed during the war , from million members in 1916 to million in 1919 . In short , American workers received better working conditions and wages , as a result of the participation in the war . However , their economic gains were limited . While prosperity overall went up during the war , it was enjoyed more by business owners and corporations than by the workers themselves . Even though wages increased , offset most of the gains . Prices in the United States increased an average of percent annually between 1917 and 1920 . Individual purchasing power actually declined during the war due to the substantially higher cost of living . Business , in contrast , increased by nearly a third during the war . Women in Wartime For women , the economic situation was complicated by the war , with the departure of men and the higher cost of living pushing many toward less comfortable lives . At the same time , however , wartime presented new opportunities for women in the workplace . More than one million women entered the workforce for the time as a result of the war , while more than eight million working women found higher paying jobs , often in industry . Many women also found employment in what were typically considered male occupations , such as on the railroads Figure ) where the number of women tripled , and on assembly lines . After the war ended and men returned home and searched for work , women were from their jobs , and expected to return home and care for their families . Furthermore , even when they were doing men jobs , women were typically paid lower wages than male workers , and unions were ambivalent at hostile at women workers . Even under these circumstances , wartime employment familiarized women with an alternative to a life in domesticity and dependency , making a life of employment , even a career , plausible for women . When , a generation later , World War II arrived , this trend would increase dramatically . FIGURE The war brought new opportunities to women , such as the training offered to those who joined the Land Army ( a ) or the opening up of traditionally male occupations . In 1918 , Eva Abbott ( was one of many new women workers on the Erie Railroad . However , once the war ended and veterans returned home , these opportunities largely disappeared . credit of work by Department of Labor ) One notable group of women who exploited these new opportunities was the Women Land Army of America . Access for free at .

A New Home Front 619 First during World War I , then again in World War II , these women stepped up to run farms and other agricultural enterprises , as men left for the armed forces ( Figure . Known as , some twenty thousand college educated and from larger urban in this capacity . Their reasons for joining were manifold . For some , it was a way to serve their country during a time of war . Others hoped to capitalize on the efforts to further the for women suffrage . Also of special note were the approximately thirty thousand American women who served in the military , as well as a variety of humanitarian organizations , such as the Red Cross and YMCA , during the war . In addition to serving as military nurses ( without rank ) American women also served as telephone operators in France . Of this latter group , 230 of them , known as Hello Girls , were bilingual and stationed in combat areas . Over eighteen thousand American women served as Red Cross nurses , providing much of the medical support available to American troops in France . Close to three hundred nurses died during service . Many of those who returned home continued to work in hospitals and home healthcare , helping wounded veterans heal both emotionally and physically from the scars of war . African Americans in the Crusade for Democracy African Americans also found that the war brought upheaval and opportunity . Black people composed 13 percent of the enlisted military , with men serving . Colonel Charles Young of the Tenth Cavalry division served as the African American . Black people served in segregated units and suffered from widespread racism in the military hierarchy , often serving in menial or support roles . Some troops saw combat , however , and were commended for serving with valor . The Infantry , for example , known as the Harlem , served on the frontline of France for six months , longer than any other American unit . One hundred men from that regiment received the Legion of Merit for meritorious service in combat . The regiment marched in a homecoming parade in New York City , was remembered in paintings Figure , and was celebrated for bravery and leadership . The accolades given to them , however , in no way extended to the bulk of African Americans in the war . FIGURE African American soldiers suffered under segregation and treatment in the military . Still , the Infantry earned recognition and reward for its valor in service both in France and the United States . On the home front , African Americans , like American women , saw economic opportunities increase during the war . During the Great Migration ( discussed in a previous chapter ) nearly African Americans had the War South for opportunities in northern urban areas . From , they moved north and found work in the steel , mining , shipbuilding , and automotive industries , among others . African American women also sought better employment opportunities beyond their traditional roles as domestic servants . By 1920 , over women had found work in diverse manufacturing industries , up from in 1910 . Despite these opportunities , racism continued to be a major force in both the North and South . Worried that Black veterans would feel empowered to change the status quo of White supremacy , many White people took political , economic , and violent action against them . In a speech on the Senate in 1917 , Mississippi

620 23 Americans and the Great War , Senator James said , Impress the negro with the fact that he is defending the , his untutored soul with military airs , teach him that it is his duty to keep the emblem of the Nation triumphantly in the is but a short step to the conclusion that his political rights must be respected . Several municipalities passed residential codes designed to prohibit African Americans from settling in certain neighborhoods . Race riots also increased in frequency In 1917 alone , there were race riots in cities , including East Saint Louis , where Black people were killed . In the South , White business and plantation owners feared that their cheap workforce was the region , and used violence to intimidate Black people into staying . According to NAACP statistics , recorded incidences of lynching increased from in 1917 to in 1919 . Dozens of Black veterans were among the victims . The frequency of these killings did not start to decrease until 1923 , when the number of annual lynchings dropped below for the time since the Civil War . CLICK AND EXPLORE Explore photographs and a written overview of the African American experience ( both at home and on the front line during World War I . THE LAST VESTIGES OF PROGRESSIVISM Across the United States , the war intersected with the last lingering efforts of the Progressives who sought to use the war as motivation for their push for change . It was in large part due to the wars that Progressives were able to lobby for the passage of the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Amendments to the Constitution . The Eighteenth Amendment , prohibiting alcohol , and the Nineteenth Amendment , giving women the right to vote , received their impetus due to the war effort . Prohibition , as the movement became known , had been a goal of many Progressives for decades . Organizations such as the Women Christian Temperance Union and the League linked alcohol consumption with any number of societal problems , and they had worked tirelessly with municipalities and counties to limit or prohibit alcohol on a local scale . But with the war , saw an opportunity for federal action . One factor that helped their cause was the strong sentiment that gripped the country , which turned sympathy away from the largely immigrants who ran the breweries . Furthermore , the public cry to ration food and latter being a key ingredient in both beer and hard prohibition even more patriotic . Congress the Eighteenth Amendment in January 1919 , with provisions to take effect one year later . the amendment prohibited the manufacture , sale , and transportation of intoxicating liquors . It did not prohibit the drinking of alcohol , as there was a widespread feeling that such language would be viewed as too intrusive on personal rights . However , by eliminating the manufacture , sale , and transport of such beverages , drinking was effectively outlawed . Shortly thereafter , Congress passed the Volstead Act , translating the Eighteenth Amendment into an enforceable ban on the consumption of alcoholic beverages , and regulating the and industrial uses of alcohol . The act also excluded from prohibition the use of alcohol for religious rituals Figure . Access for free at .

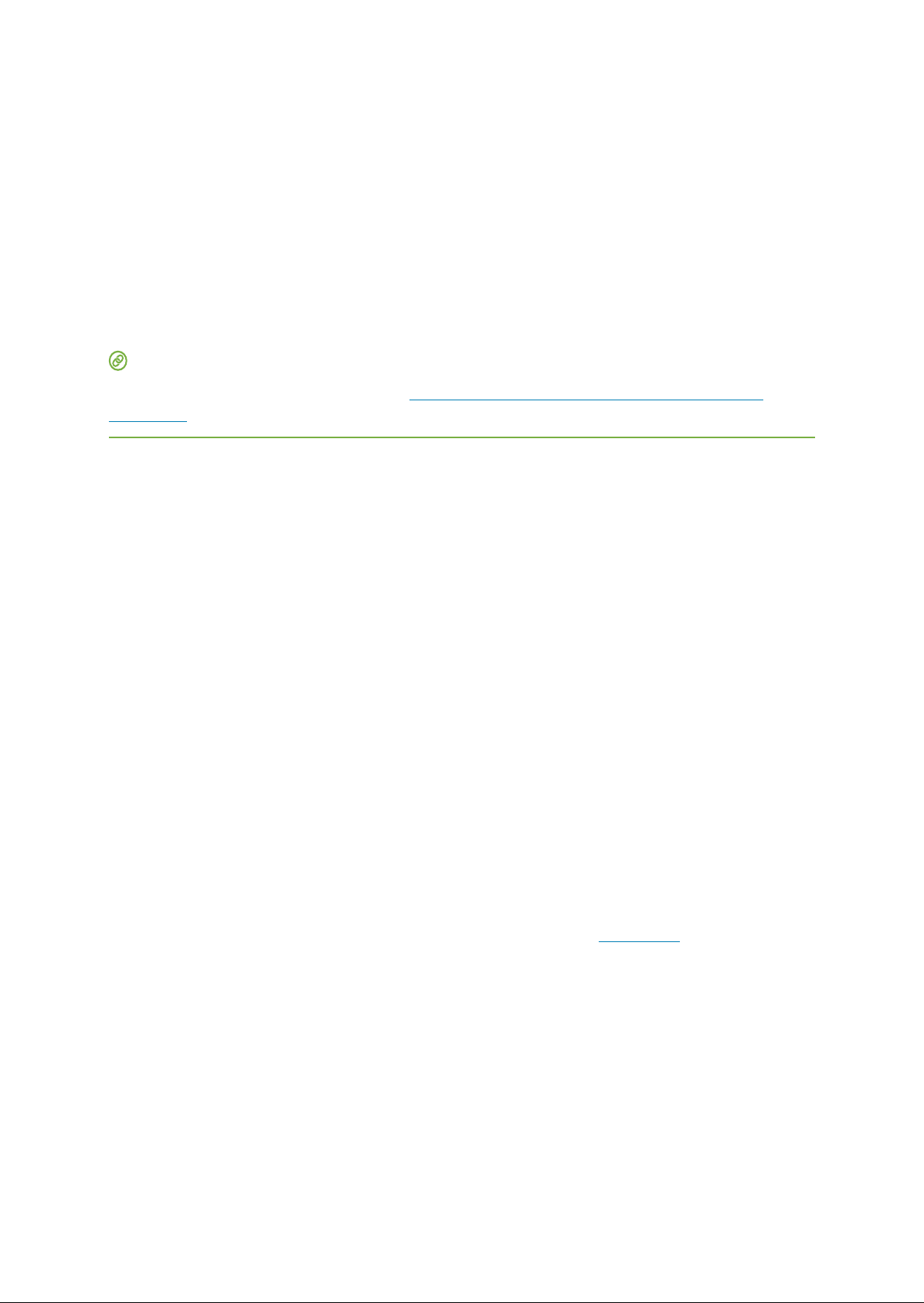

A New Home Front 621 FIGURE Surrounded by prominent dry workers , Governor James of Indiana signs a statewide bill to prohibit alcohol . Unfortunately for proponents of the amendment , the ban on alcohol did not take effect until one full year following the end of the war . Almost immediately following the war , the general public began to clearly law , making it very difficult to enforce . Doctors and druggists , who could prescribe whisky for medicinal purposes , found themselves inundated with requests . In the , organized crime and gangsters like Al Capone would capitalize on the persistent demand for liquor , making fortunes in the illegal trade . A lack of enforcement , compounded by an overwhelming desire by the public to obtain alcohol at all costs , eventually resulted in the repeal of the law in 1933 . The First World War also provided the impetus for another longstanding goal of some reformers universal suffrage . Supporters of equal rights for women pointed to Wilson rallying cry of a war to make the world safe for democracy , as hypocritical , saying he was sending American boys to die for such principles while simultaneously denying American women their democratic right to vote Figure 2314 . Carrie Chapman , president of the National American Women Suffrage Movement , capitalized on the growing patriotic fervor to point out that every woman who gained the vote could exercise that right in a show of loyalty to the nation , thus offsetting the dangers of or naturalized Germans who already had the right to vote . Alice Paul , of the National Women Party , organized more radical tactics , bringing national attention to the issue of women suffrage by organizing protests outside the White House and , later , hunger strikes among arrested protesters . African American , who had been active in the movement for decades , faced discrimination from their White counterparts . Some White leaders this treatment based on the concern that promoting Black women would erode public support . For example , leaders of the convention 1911 disallowed an amendment adding race as an element of the organization platform based on the idea that White men would oppose the entire movement . But overt racism played a role , as well . In response , Black had formed what would become the National Association of Colored Women Clubs . Its most prominent leaders , Josephine Pierre and Mary Church Terrell , led the organization in its efforts for women rights , ending lynchings , and raising money for social services such as orphanages and homes for the elderly . The did not always align with the even though they were moving toward the same general goals . At some points , the organizations came into direct confrontation . During the suffrage parade in 1913 , Black members were told to march at the rear of the line . Ida , a prominent voice for equality , asked her local delegation to oppose this segregation they refused . Not to be dismissed , waited in the crowd until the Illinois delegation passed by , then stepped onto the parade route and took her place among them . By the end of the war , the abusive treatment of suffragist in prison , important contribution to the war effort , and the arguments of his suffragist daughter Jessie Woodrow Wilson moved President Wilson to understand women right to vote as an ethical mandate for a true

622 23 Americans and the Great War , democracy . He began urging congressmen and senators to adopt the legislation . The amendment passed in June 1919 , and the states it by August 1920 . the Nineteenth Amendment prohibited all efforts to deny the right to vote on the basis of sex . It took effect in time for American women to vote in the presidential election of 1920 . FIGURE picketed the White House in 1917 , leveraging the war and America stance on democracy to urge Woodrow Wilson to support an amendment giving women the right to vote . From Peace LEARNING OBJECTIVES By the end ofthis section , you will be able to role that the United States played at the end of World Warl Describe Woodrow Wilson vision for the postwar world Explain why the United States never formally approved the Treaty of Versailles nor joined the League of Nations The American role in World War I was brief but decisive . While millions of soldiers went overseas , and many thousands paid with their lives , the country involvement was limited to the very end of the war . In fact , the peace process , with the international conference and subsequent process , took longer than the time soldiers were in country in France . For the Allies , American reinforcements came at a decisive moment in their defense of the western front , where a offensive had exhausted German forces . For the United States , and for Wilson vision of a peaceful future , the was faster and more successful than what was to follow . WINNING THE WAR When the United States declared war on Germany in April 1917 , the Allied forces were close to exhaustion . Great Britain and France had already indebted themselves heavily in the procurement of vital American military supplies . Now , facing defeat , a British delegation to Washington , requested immediate troop reinforcements to boost Allied spirits and help crush German morale , which was already weakened by short supplies on the frontlines and hunger on the home front . Wilson agreed and immediately sent American troops in June 1917 . These soldiers were placed in quiet zones while they trained and prepared for combat . By March 1918 , the Germans had won the war on the eastern front . The Russian Revolution of the previous year had not only toppled the hated regime of Tsar Nicholas II but also ushered in a civil war from which the Bolshevik faction of Communist revolutionaries under the leadership of Vladimir Lenin emerged victorious . Weakened by war and internal strife , and eager to build a new Soviet Union , Russian delegates agreed to a generous peace treaty with Germany . Thus emboldened , Germany quickly moved upon the Allied lines , causing both the French and British to ask Wilson to forestall extensive training to troops and instead Access for free at .

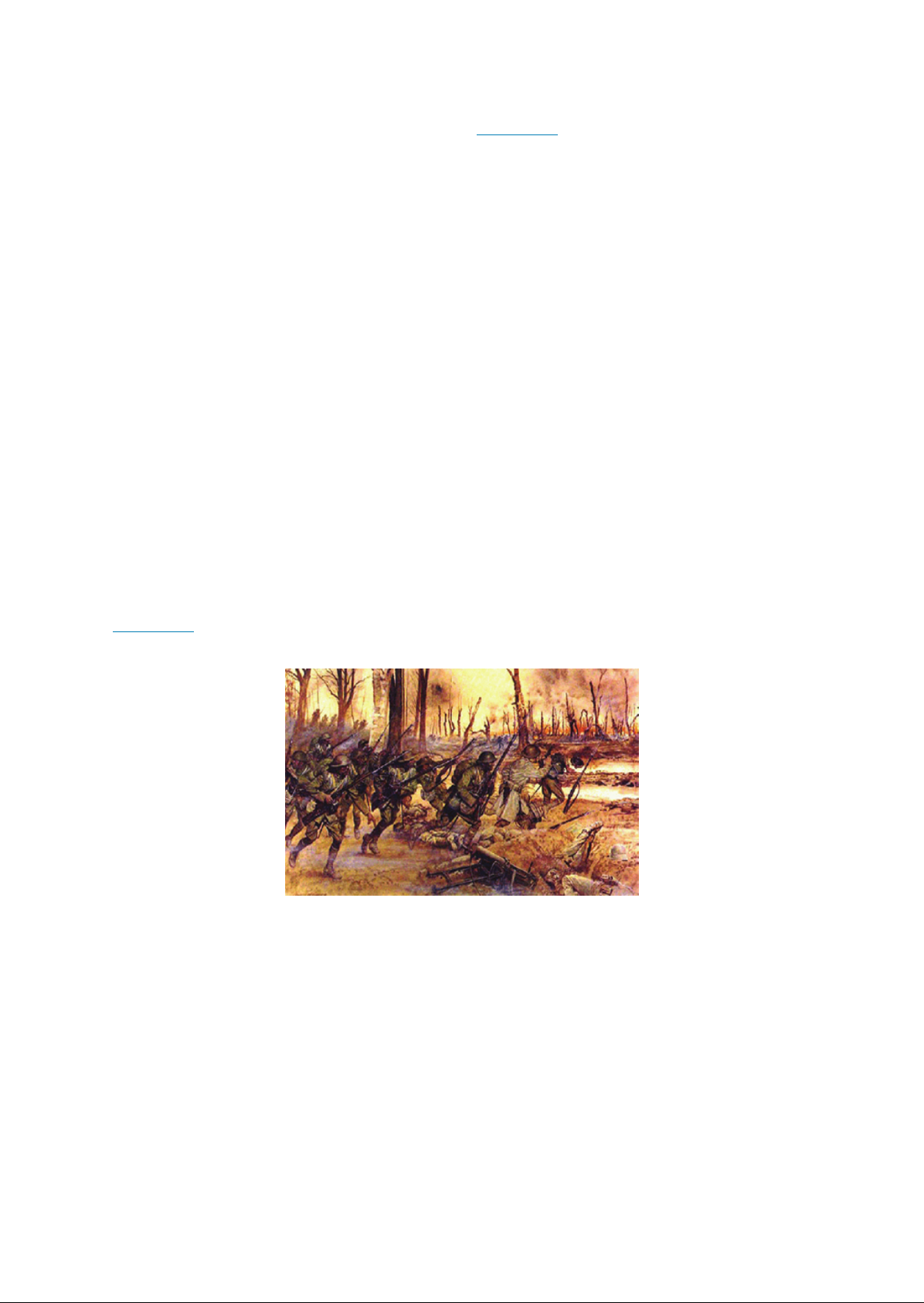

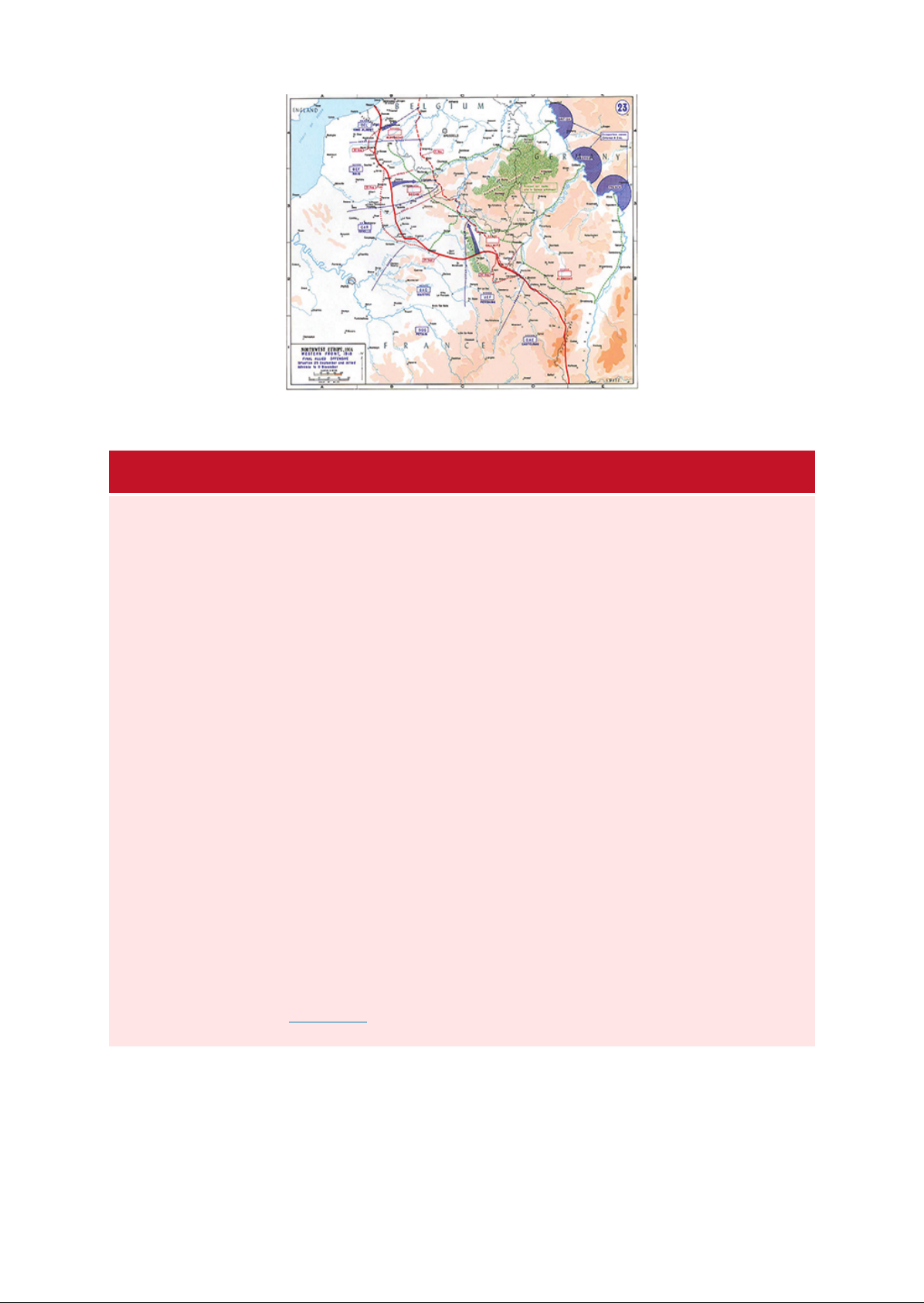

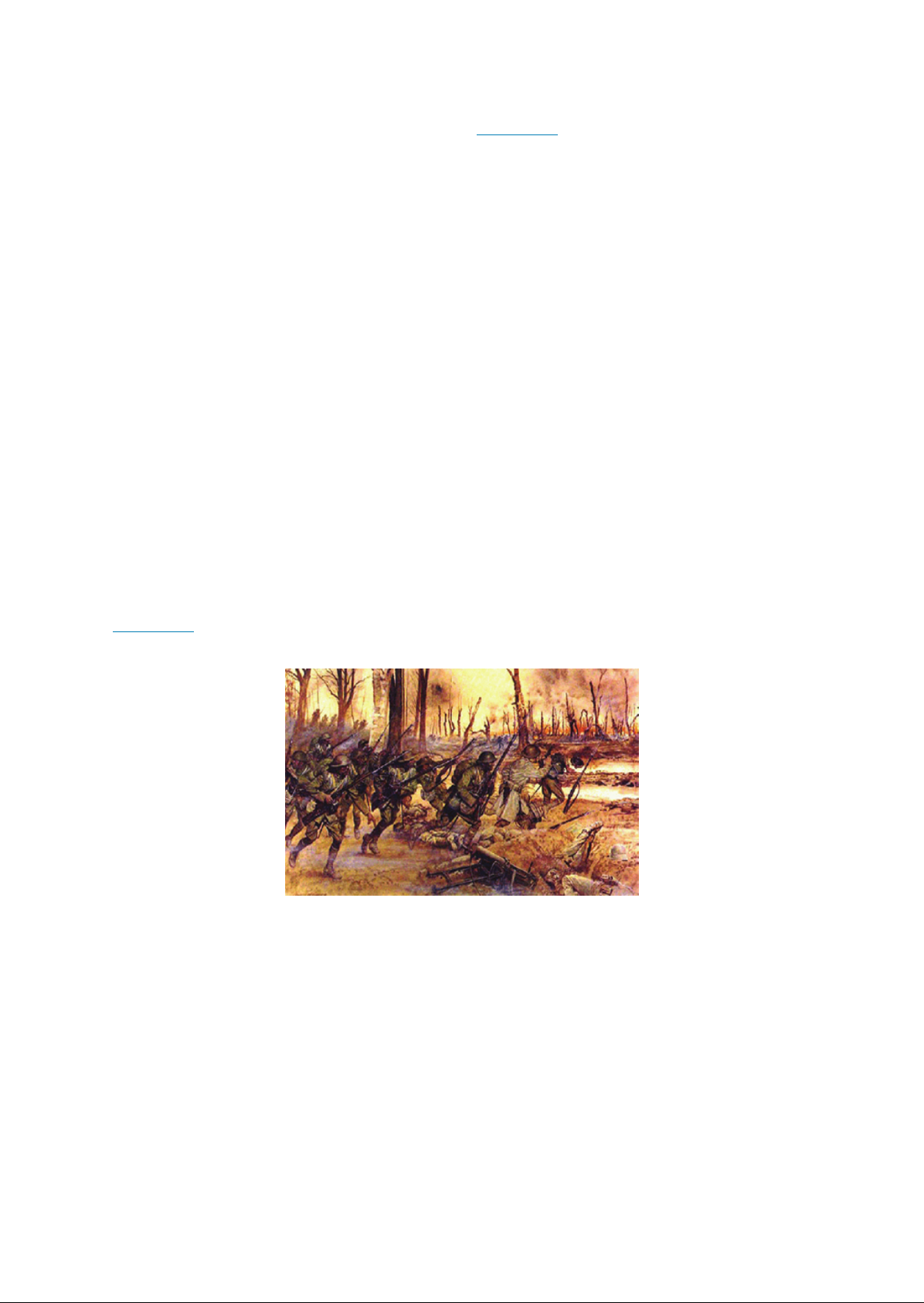

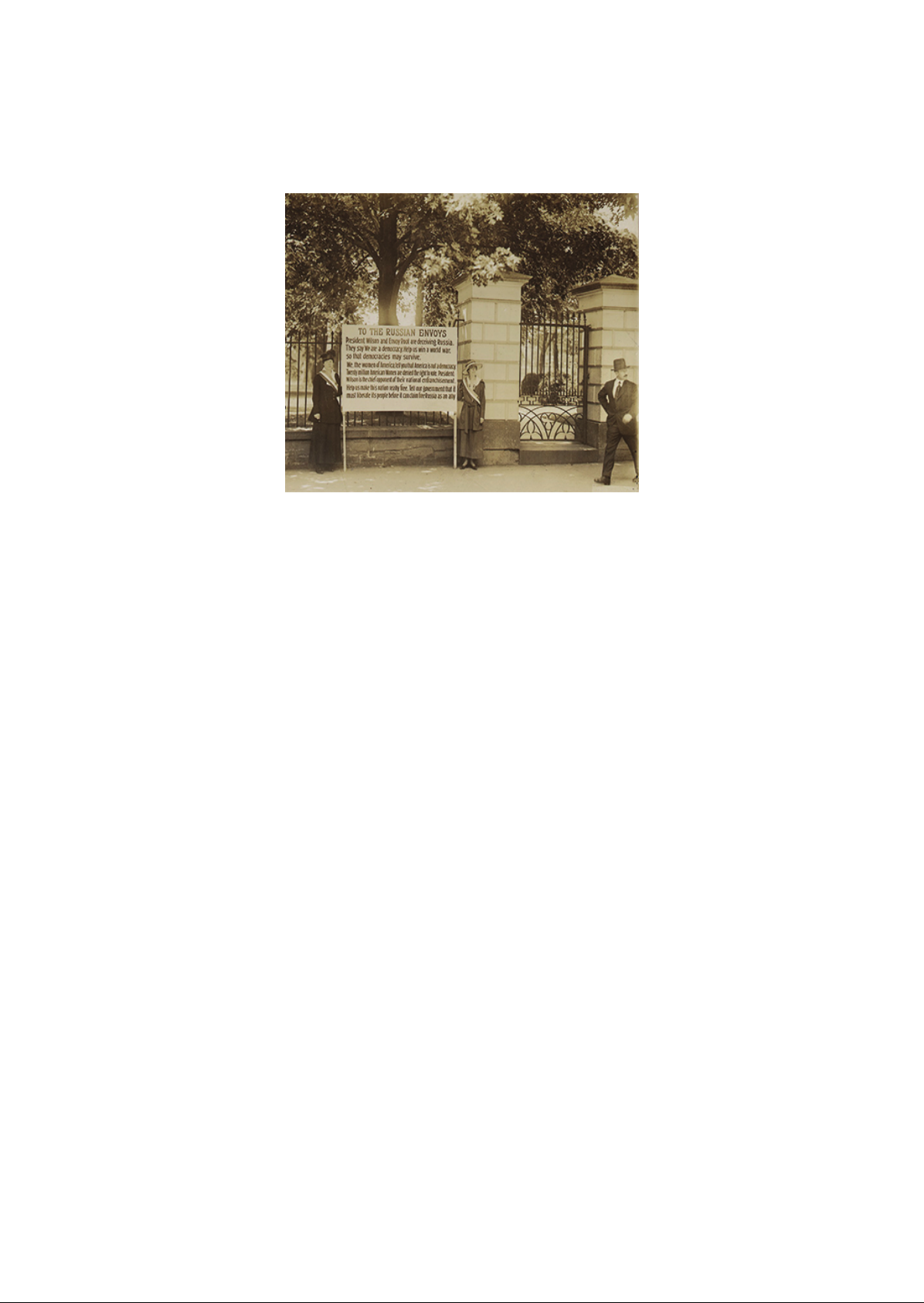

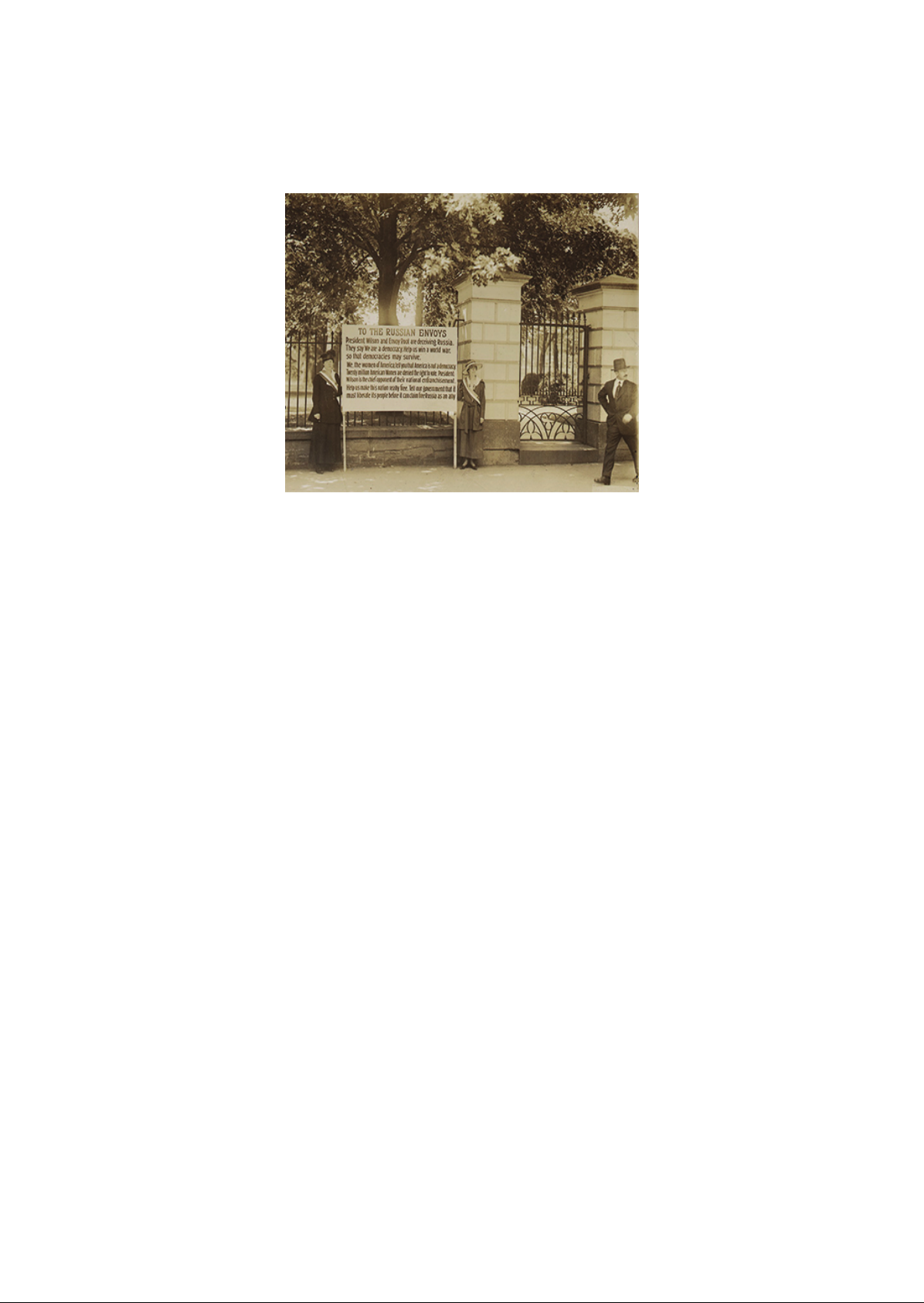

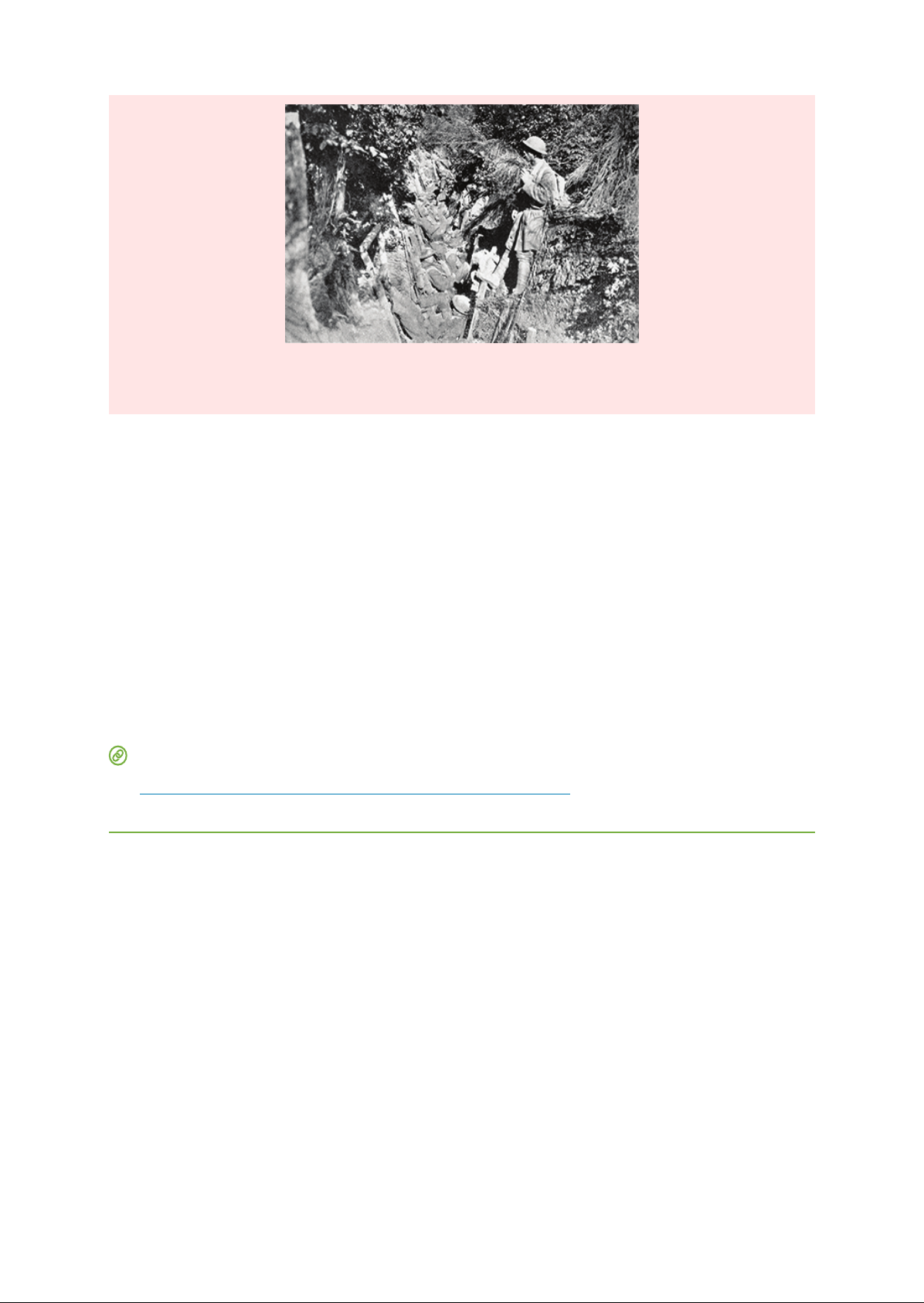

From War to Peace 623 commit them to the front immediately . Although wary of the move , Wilson complied , ordering the commander of the American Expeditionary Force , General John Blackjack Pershing , to offer troops as replacements for the Allied units in need of relief . By May 1918 , Americans were fully engaged in the war ( Figure . FIGURE soldiers run past fallen Germans on their way to a bunker . In World War I , forthe time , photographs ofthe battles brought the war vividly to life for those at home . In a series of battles along the front that took place from May 28 through August , 1918 , including the battles of , Chateau Thierry , Wood , and the Second Battle of the , American forces alongside the British and French armies succeeded in repelling the German offensive . The Battle of , on May 28 , was the American offensive in the war In less than two hours that morning , American troops overran the German headquarters in the village , thus convincing the French commanders of their ability to against the German line advancing towards Paris . The subsequent battles of Chateau Thierry and Wood proved to be the bloodiest of the war for American troops . At the latter , faced with a German onslaught of mustard gas , artillery , and mortar , Marines attacked German units in the woods on six times meeting them in and bayonet repelling the advance . The forces suffered casualties in the battle , with almost killed in total and on a single day . Brutal as they were , they amounted to small losses compared to the casualties suffered by France and Great Britain . Still , these summer battles turned the tide of the war , with the Germans in full retreat by the end of July 1918 ( Figure .

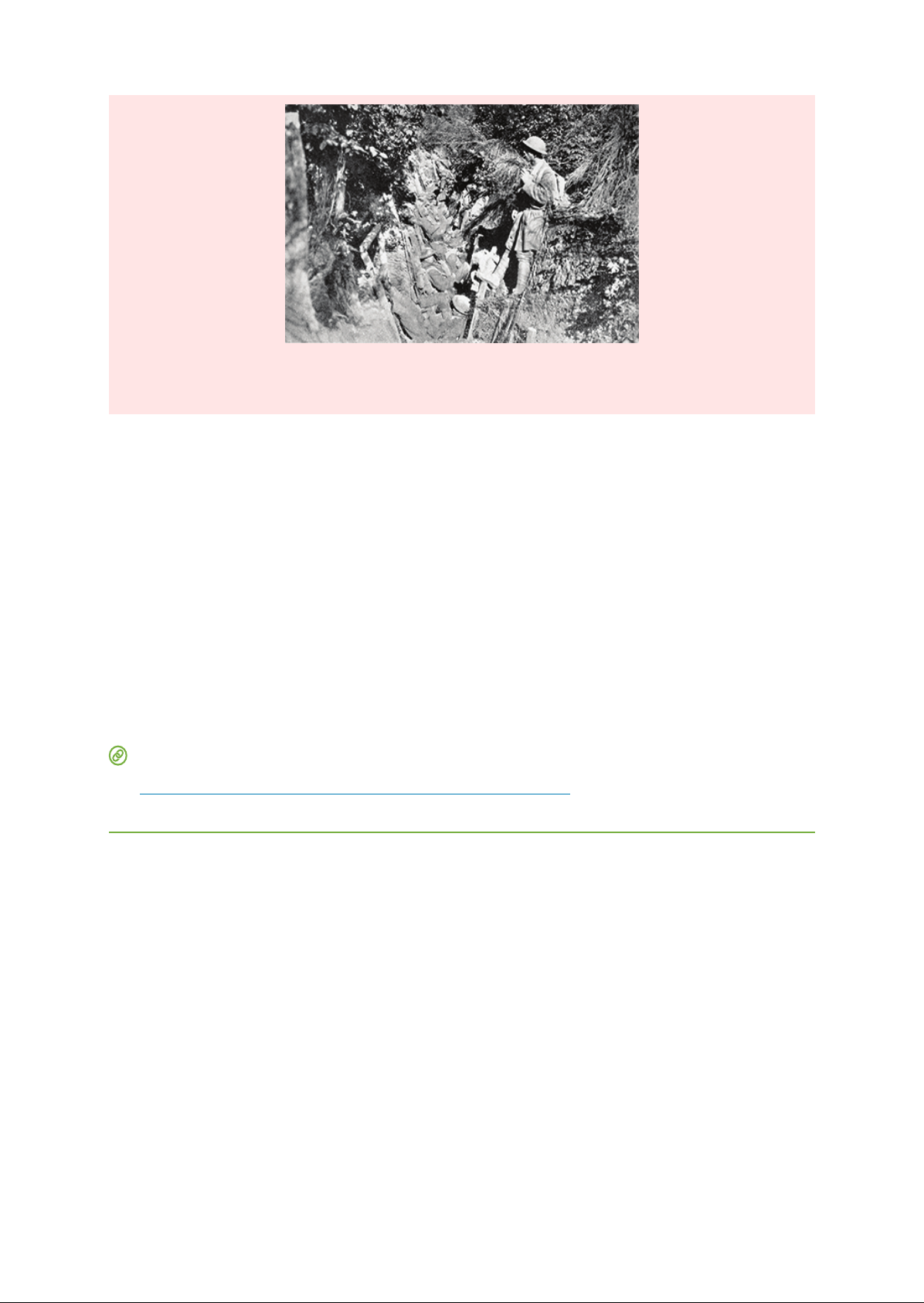

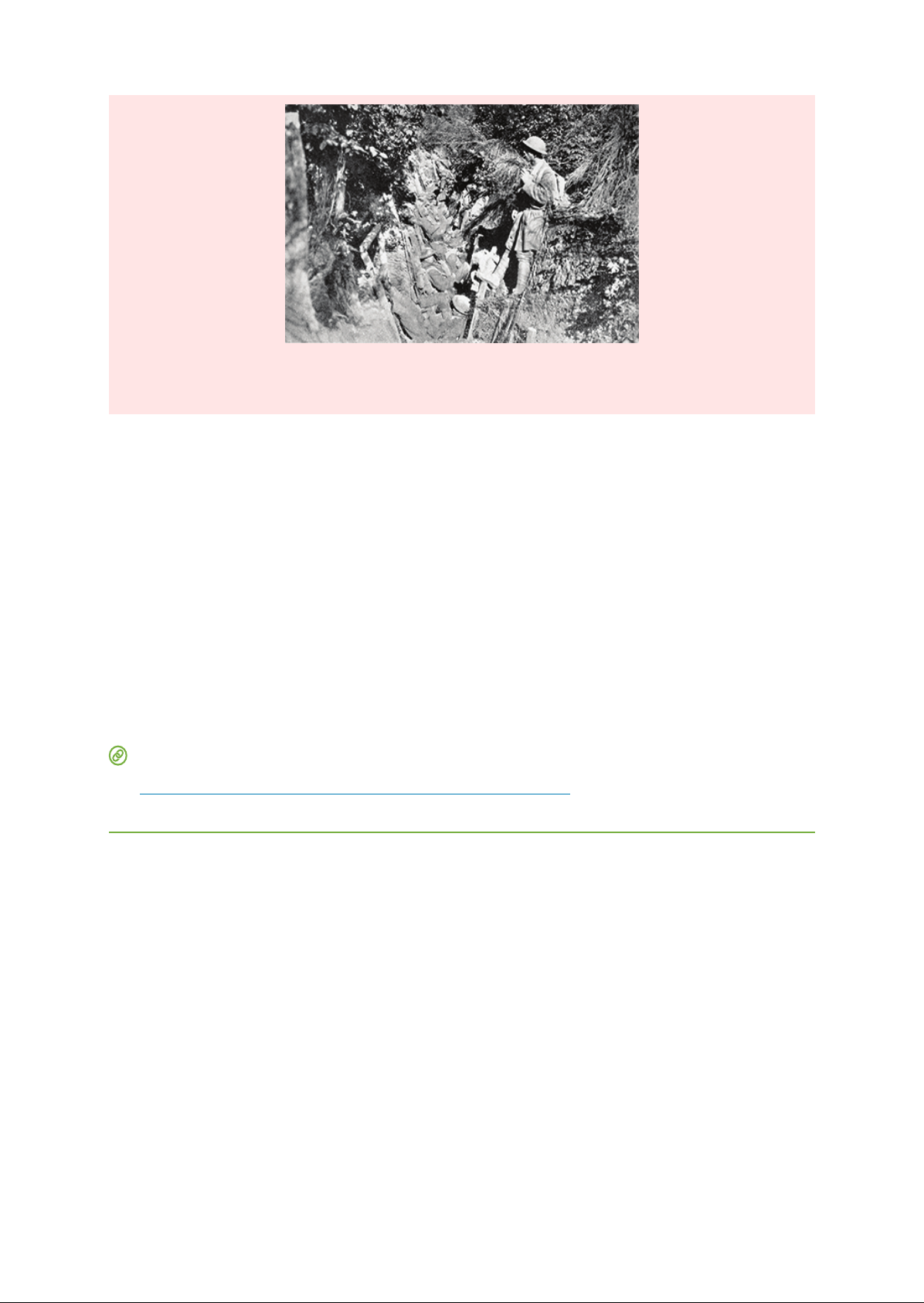

624 23 Americans and the Great War , FIGURE This map shows the western front at the end of the war , as the Allied Forces decisively break the German line . MY STORY . Charles Leon Boucher Life and Death in the Trenches of France Wounded in his shoulder by enemy forces , George , a machine gunner posted on the right end of the American platoon , was taken prisoner at the Battle of in 1918 . However , as darkness set in that evening , another American soldier , Charlie , heard a noise from a gully beside the trench in which he had hunkered down . I it must be the enemy patrol , Charlie later said . I only had a couple of bullets left in the chamber my . The noise stopped and a head popped into sight . When I was about to , I gave another look and a white and distorted face proved to be that of George , so I grabbed his shoulders and pulled him down into our trench beside me . He must have had about twenty bullet holes in him but not one of them was well placed enough to kill him . He made an effort to speak so I told him to keep quiet and conserve his energy . I had a few ma ted milk tablets left and , I forced them into his mouth . I also poured the last ofthe water I had left in my canteen into his mouth . Following a harrowing night , they began to crawl along the road back to their platoon . As they crawled , George explained how he survived being captured . Charlie ater told how George was taken to an enemy First Aid Station where his wounds were dressed . Then the motioned to have him taken to the rear oftheir lines . But , the Sergeant Major pushed him towards our sice and No Mans Land , pulled out his Luger Automatic and shot him down . Then , he began to crawl towards our lines little by little , being shot at consistently by the enemy snipers till , he arrived in our position . The story of Charlie and George , related later in life . Charles Leon Boucher to his grandson , was one replayed many times over in various forms duringthe American Expeditionary Force involvement in World War I . The industrial scale of death and destruction was as new to American soldiers as to their European counterparts , and the survivors brought home physical and psychological scars that influenced the United States long war was won Figure 2317 . Access for free at .

From War to Peace 625 , FIGURE This photograph of soldiers in a trench hardly begins to capture the brutal conditions of trench warfare , where disease , rats , mud , and hunger plagued the men . By the end of September 1918 , over one million soldiers staged a full offensive into the Forest . By nearly forty days of intense German lines were broken , and their military command reported to German Emperor Kaiser Wilhelm II of the desperate need to end the war and enter into peace negotiations . Facing civil unrest from the German people in Berlin , as well as the loss of support from his military high command , Kaiser Wilhelm abdicated his throne on November , 1918 , and immediately by train to the Netherlands . Two days later , on November 11 , 1918 , Germany and the Allies declared an immediate armistice , thus bring the to a stop and signaling the beginning of the peace process . When the armistice was declared , a total of American soldiers had been killed and wounded . The Allies as a whole suffered over million military deaths , primarily Russian , British , and French men . The Central powers suffered four million military deaths , with half of them German soldiers . The total cost of the war to the United States alone was in excess of 32 billion , with interest expenses and veterans eventually bringing the cost to well over 100 billion . Economically , emotionally , and geopolitically , the war had taken an enormous toll . CLICK AND EXPLORE This Smithsonian interactive exhibit ( offers a fascinating perspective on World War I . THE BATTLE FOR PEACE While Wilson had been loath to involve the United States in the war , he saw the country eventual participation as for America involvement in developing a moral foreign policy for the entire world . The new world order he wished to create from the outset of his presidency was now within his grasp . The United States emerged from the war as the predominant world power . Wilson sought to capitalize on that and impose his moral foreign policy on all the nations of the world . The Paris Peace Conference As early as January full months before military forces their shot in the war , and eleven months before the actual announced his postwar peace plan before a joint session of Congress . Referring to what became known as the Fourteen Points , Wilson called for openness in all matters of diplomacy and trade , free trade , freedom of the seas , an end to secret treaties and negotiations , promotion of of all nations , and more . In addition , he called for the creation of a League of Nations to promote the new world order and preserve territorial integrity through open discussions in place of intimidation and war .

626 23 Americans and the Great War , As the war concluded , Wilson announced , to the surprise of many , that he would attend the Paris Peace Conference himself , rather than ceding to the tradition of sending professional diplomats to represent the country ( Figure 2318 ) His decision other nations to follow suit , and the Paris conference became the largest meeting ofworld leaders to date in history . For six months , beginning in December 1918 , Wilson remained in Paris to personally conduct peace negotiations . Although the French public greeted Wilson with overwhelming enthusiasm , other delegates at the conference had deep misgivings about the American president plans for a peace without victory . Great Britain , France , and Italy sought to obtain some measure of revenge against Germany for drawing them into the war , to secure themselves against possible future aggressions from that nation , and also to maintain or even strengthen their own colonial possessions . Great Britain and France in particular sought substantial monetary reparations , as well as territorial gains , at Germany expense . Japan also desired concessions in Asia , whereas Italy sought new territory in Europe . Finally , the threat posed by a Bolshevik Russia under Vladimir Lenin , and more importantly , the danger of revolutions elsewhere , further spurred on these allies to use the treaty negotiations to expand their territories and secure their strategic interests , rather than strive towards world peace . FIGURE The Paris Peace Conference held the largest number of world leaders in one place to date . The photograph shows ( from left to right ) Prime Minister David Lloyd George of Great Britain Vittorio Emanuele Orlando , prime minister of Italy Georges , prime minister of France and President Woodrow Wilson discussing the terms ofthe peace . In the end , the Treaty of Versailles that concluded World War I resembled little of Wilson original Fourteen Points . The Japanese , French , and British succeeded in carving up many of Germany colonial holdings in Africa and Asia . The dissolution of the Ottoman Empire created new nations under the colonial rule of France and Great Britain , such as Iraq and Palestine . France gained much of the disputed territory along their border with Germany , as well as passage of a war guilt clause that demanded Germany take public responsibility for starting and prosecuting the war that led to so much death and destruction . Great Britain led the charge that resulted in Germany agreeing to pay reparations in excess of 33 billion to the Allies . As for Bolshevik Russia , Wilson had agreed to send American troops to their northern region to protect Allied supplies and holdings there , while also participating in an economic blockade designed to undermine Lenin power . This move would ultimately have the opposite effect of galvanizing popular support for the Bolsheviks . The sole piece of the original Fourteen Points that Wilson successfully fought to keep intact was the creation of a League of Nations . At a covenant agreed to at the conference , all member nations in the League would agree to defend all other member nations against military threats . Known as Article , this agreement would basically render each nation equal in terms of power , as no member nation would be able to use its military Access for free at .

Demobilization and Its Difficult Aftermath 627 might against a weaker member nation . Ironically , this article would prove to be the undoing of Wilson dream of a new world order . Ratification of the Treaty of Versailles Although the other nations agreed to the terms of the Treaty of Versailles , Wilson greatest battle lay in he debate that awaited him upon his return . As with all treaties , this one would require approval by the Senate for , something Wilson knew would be to achieve . Even Wilson return to Washington , Senator Henry Cabot Lodge , chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee that oversaw proceedings , issued a list of fourteen reservations he had regarding the reaty , most of which centered on the creation of a League of Nations . An isolationist in foreign policy issues , Lodge feared that Article would require extensive American intervention , as more countries would seek her in all controversial affairs . But on the other side of the political spectrum , interventionists argued hat Article would impede the United States from using her rightfully attained military power to secure and America international interests . Wilson greatest was with the Senate , where most Republicans opposed the treaty due to the clauses surrounding the creation of the League of Nations . Some Republicans , known as , opposed the reaty on all grounds , whereas others , called , would support the treaty if amendments were introduced that could eliminate Article . In an effort to turn public support into a weapon against those in opposition , Wilson embarked on a railway speaking tour . He began travelling in September 1919 , and the grueling pace , after the stress of the six months in Paris , proved too much . Wilson following a public event on September 25 , 1919 , and immediately returned to Washington . There he suffered a debilitating stroke , leaving his second wife Edith Wilson in charge as de facto president for a period of about six months . Frustrated that his dream of a new world order was slipping frustration that was compounded by the fact that , now an invalid , he was unable to speak his own thoughts urged Democrats in the Senate to reject any effort to compromise on the treaty . As a result , Congress voted on , and defeated , the originally worded treaty in November . When the treaty was introduced with reservations , or amendments , in March 1920 , it again fell short of the necessary margin for . As a result , the United States never became an signatory of the Treaty of Versailles . Nor did the the League of Nations , which shattered the international authority and of the organization . Although Wilson received the Nobel Peace Prize in October 1919 for his efforts to create a model of world peace , he remained personally embarrassed and angry at his country refusal to be a part of that model . As a result of its rejection of the treaty , the United States technically remained at war with Germany until July 21 , 1921 , when it formally came to a close with Congress quiet passage of the Resolution . CLICK AND EXPLORE Read about the Treaty of Versailles ( here , particularly how it sowed the seeds for Hitler rise to power and World War II . Demobilization and Its Difficult Aftermath LEARNING OBJECTIVES By the end ofthis section , you will be able to challenges that the United States faced conclusion of World War I Explain Warren Harding landslide victory in the 1920 presidential election As world leaders debated the terms of the peace , the American public faced its own challenges at the conclusion of the First World War . Several unrelated factors intersected to create a chaotic and time , just as massive numbers of troops rapidly demobilized and came home . Racial tensions , a terrifying

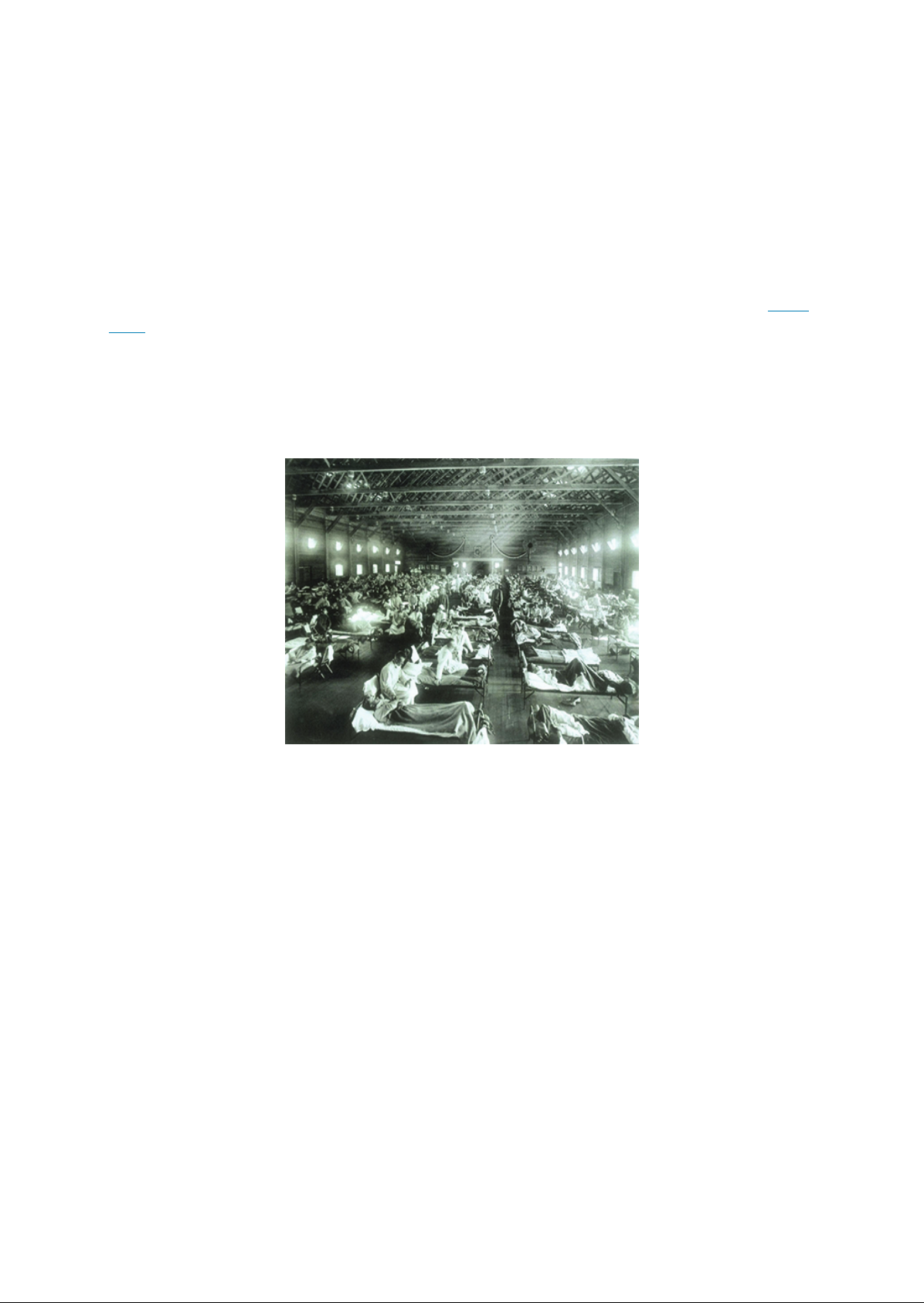

628 23 Americans and the Great War , epidemic , anticommunist hysteria , and economic uncertainty all combined to leave many Americans wondering what , exactly , they had won in the war . Adding to these problems was the absence of President Wilson , who remained in Paris for six months , leaving the country leaderless . The result of these factors was that , rather than a celebratory transition from wartime to peace and prosperity , and ultimately the Jazz Age of the , 1919 was a tumultuous year that threatened to tear the country apart . DISORDER AND FEAR IN AMERICA After the war ended , troops were demobilized and rapidly sent home . One unanticipated and unwanted effect of their return was the emergence of a new strain of that medical professionals had never before encountered . Within months of the war end , over twenty million Americans fell ill from the ( Figure Eventually , Americans died before the disease mysteriously ran its course in the spring of 1919 . Worldwide , recent estimates suggest that 500 million people suffered from this strain , with as many as million people dying . Throughout the United States , from the fall of 1918 to the spring of 1919 , fear of the gripped the country . Americans avoided public gatherings , children wore surgical masks to school , and undertakers ran out of and burial plots in cemeteries . Hysteria grew as well , and instead of welcoming soldiers home with a postwar celebration , people hunkered down and hoped to avoid contagion . FIGURE The flu pandemic of 1918 , commonly called Spanish Flu at the time , swept across the United States , resulting in overcrowded flu wards like this one in Camp , Kansas , and adding another trauma onto the recovering postwar psyche . Another element that greatly the challenges of immediate postwar life was economic upheaval . As discussed above , wartime production had led to steady the rising cost of living meant that few Americans could comfortably afford to live off their wages . When the government wartime control over the economy ended , businesses slowly recalibrated from the wartime production of guns and ships to the peacetime production of toasters and cars . Public demand quickly outpaced the slow production , leading to notable shortages of domestic goods . As a result , skyrocketed in 1919 . By the end of the year , the cost of living in the United States was nearly double what it had been in 1916 . Workers , facing a shortage in wages to buy more expensive goods , and no longer bound by the pledge they made for the National War Labor Board , initiated a series of strikes for better hours and wages . In 1919 alone , more than four million workers participated in a total of nearly three thousand strikes both records within all of American history . In addition to labor clashes , race riots shattered the peace at the home front . The race riots that had begun during the Great Migration only grew in postwar America . White soldiers returned home to Black workers in their former jobs and neighborhoods , and were committed to restoring their position of White supremacy . Black soldiers returned home with a renewed sense of justice and strength , and were determined to assert their rights as men and as citizens . Meanwhile , southern lynchings continued to escalate , with White mobs burning African Americans at the stake . The mobs often used false accusations of indecency and assault on Access for free at .

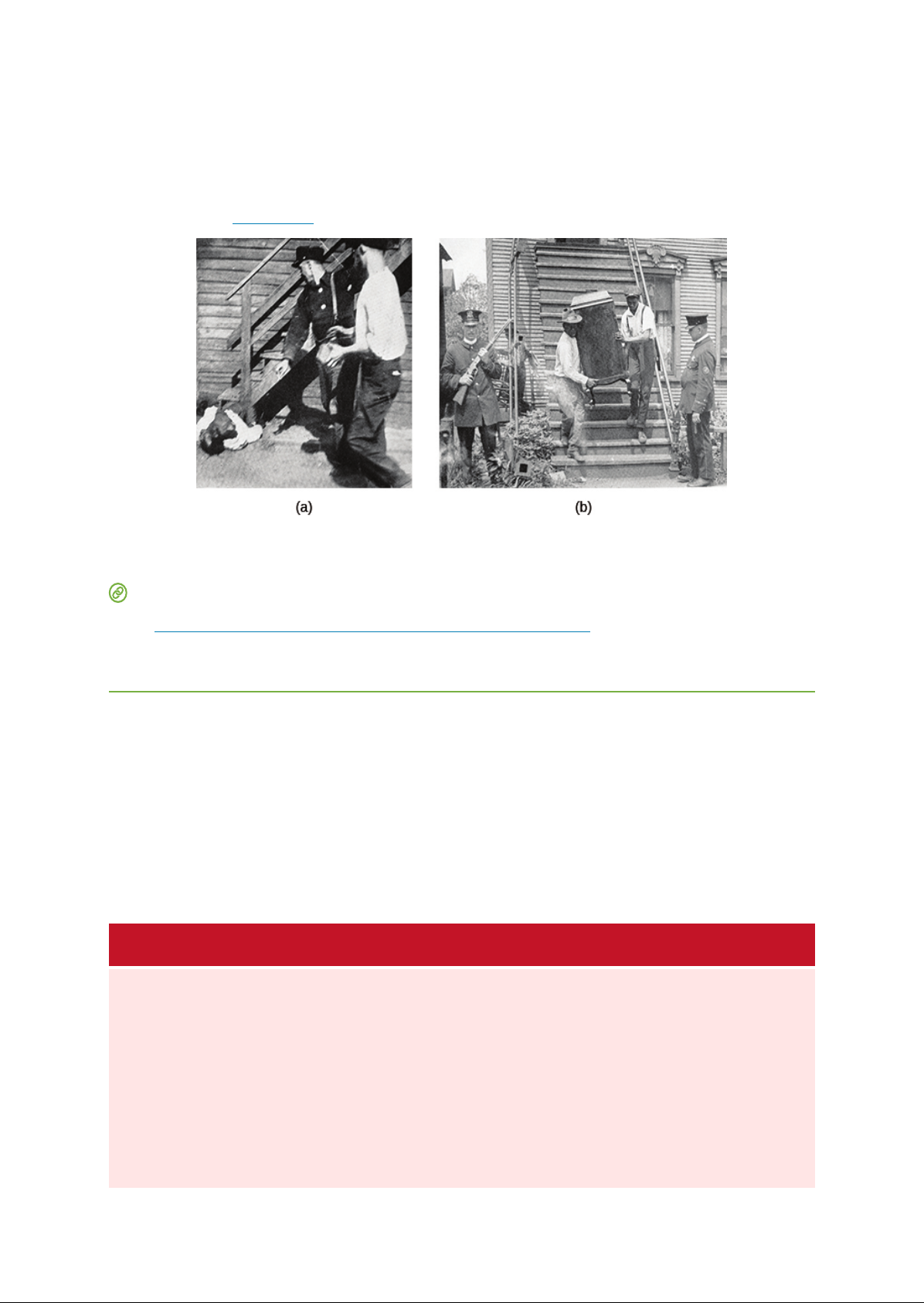

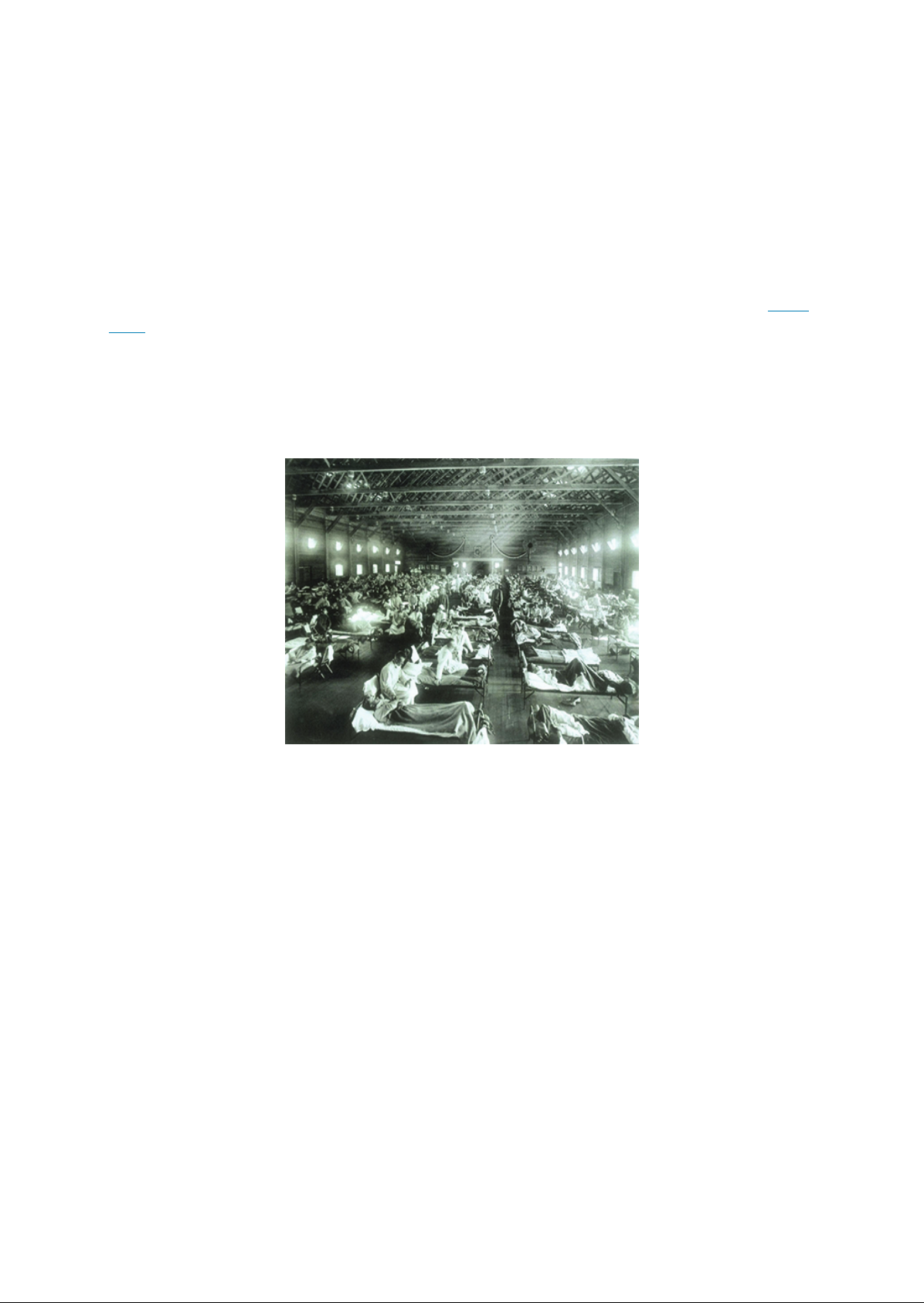

Demobilization and Its Difficult Aftermath 629 White women to justify the murders . During the Red Summer of 1919 , northern cities recorded bloody race riots that killed over 250 people . Among these was the Chicago Race Riot of 1919 , where a White mob stoned a young Black boy to death because he swam too close to the White beach on Lake Michigan . Police at the scene did not arrest the perpetrator who threw the rock . This crime prompted a riot that left Black people and White people dead , as well as millions of dollars worth of damage to the city ( Figure 2320 . FIGURE Riots broke out in Chicago in the wake of the stoning of a Black boy . After two weeks , more people had died , some were stoned ( a ) and many had to abandon their vandalized homes ( CLICK AND EXPLORE Read a Chicago newspaper report ( of the race riot , as well as a commentary on how the different written for the Black community as well as those written by the mainstream to sensationalize the story . A massacre in Tulsa , Oklahoma , in 1921 , turned out even more deadly , with estimates of Black fatalities ranging from to three hundred . Again , the violence arose based on a dubious allegation of assault on a White girl by a Black teenager . After an incendiary newspaper article , a at the courthouse led to ten White and two Black peoples deaths . A riot ensued , with White groups pursuing Black people as they retreated to the Greenwood section of the city . Both sides were armed , and and arson continued throughout the night . The next morning , the White groups began an assault on the Black neighborhoods , killing many Black residents and destroying homes and businesses . The Tulsa Massacre ( also called the Tulsa Riot , Greenwood Massacre , or Black Wall Street Massacre ) was widely reported at the time , but was omitted from many historical recollections , textbooks , and media for decades . MY STORY The Tulsa Race Riot and Three of Its Victims . Franklin was a prominent Black lawyer in Tulsa , Oklahoma . A survivor of the Tulsa Massacre , he penned a account ten years after the events . The manuscript was uncovered in 2015 and has been published by the Smithsonian . About , I arose and went to the north porch on the second floor of my hotel and , looking in a westerly direction , I saw the top of hill literally lighted up by blazes that came from the throats of machine guns , and I could hear bullets whizzing and cutting the air . There was shooting now in every direction , and the sounds that came from the thousands and thousands of guns were deafening

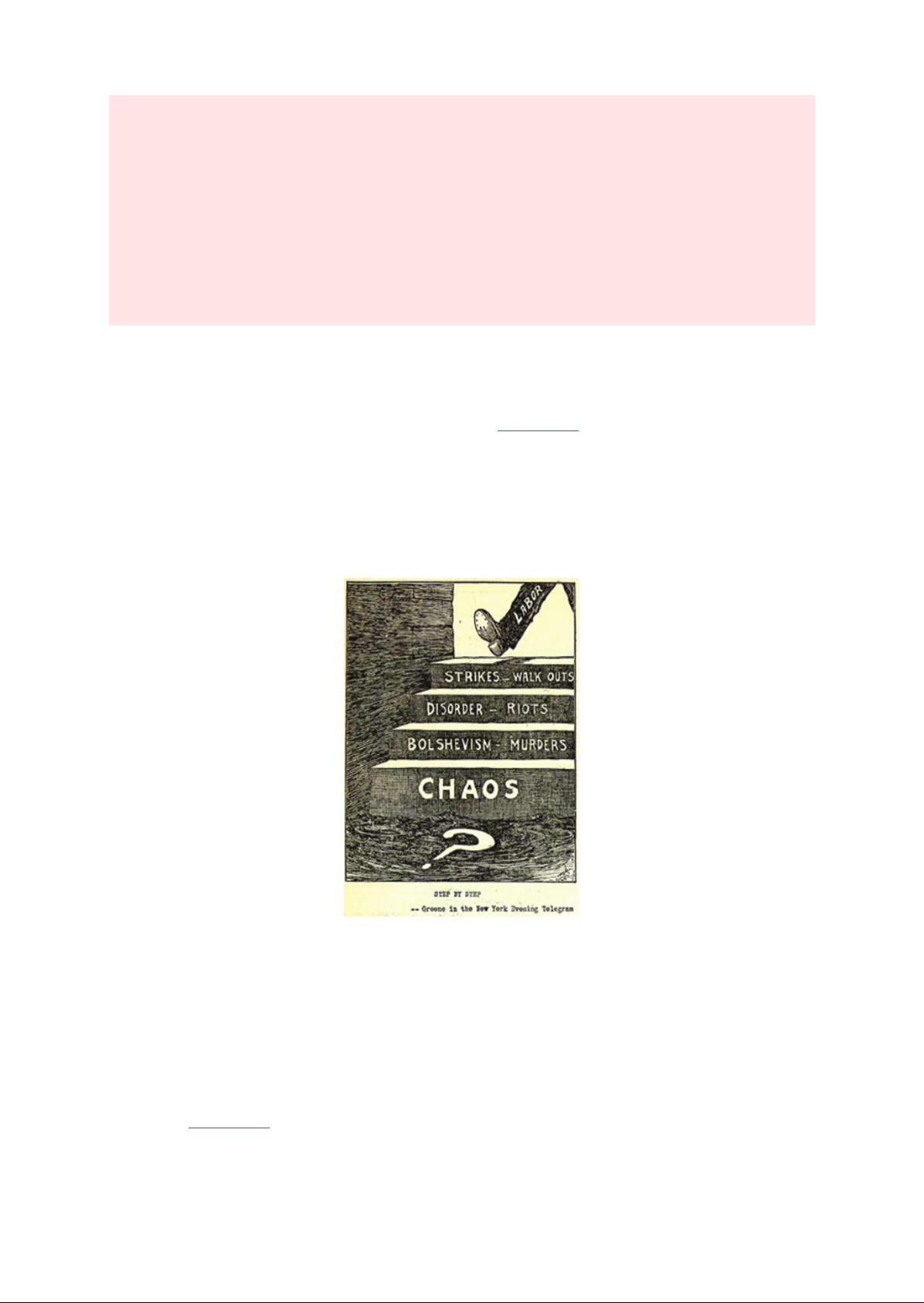

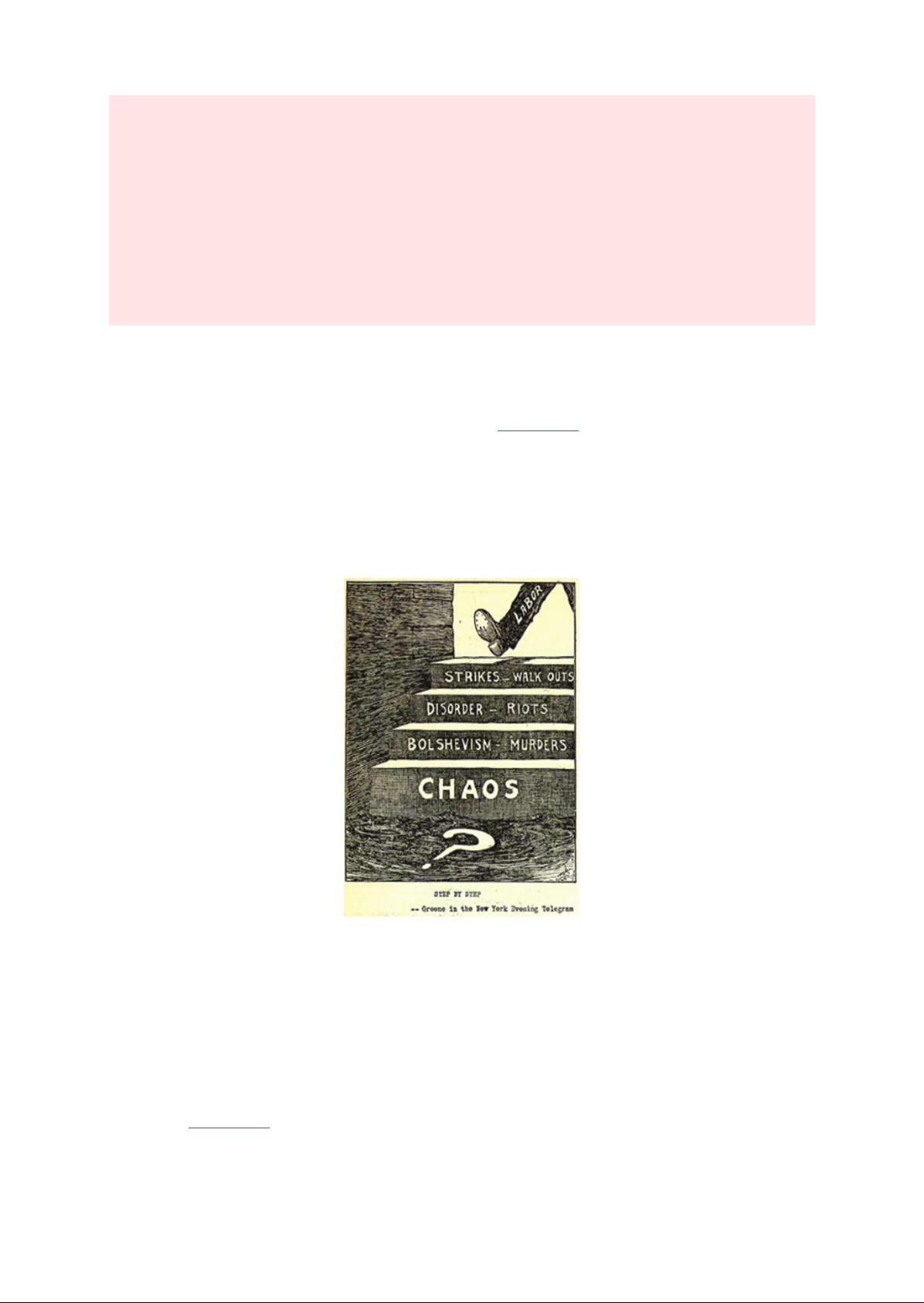

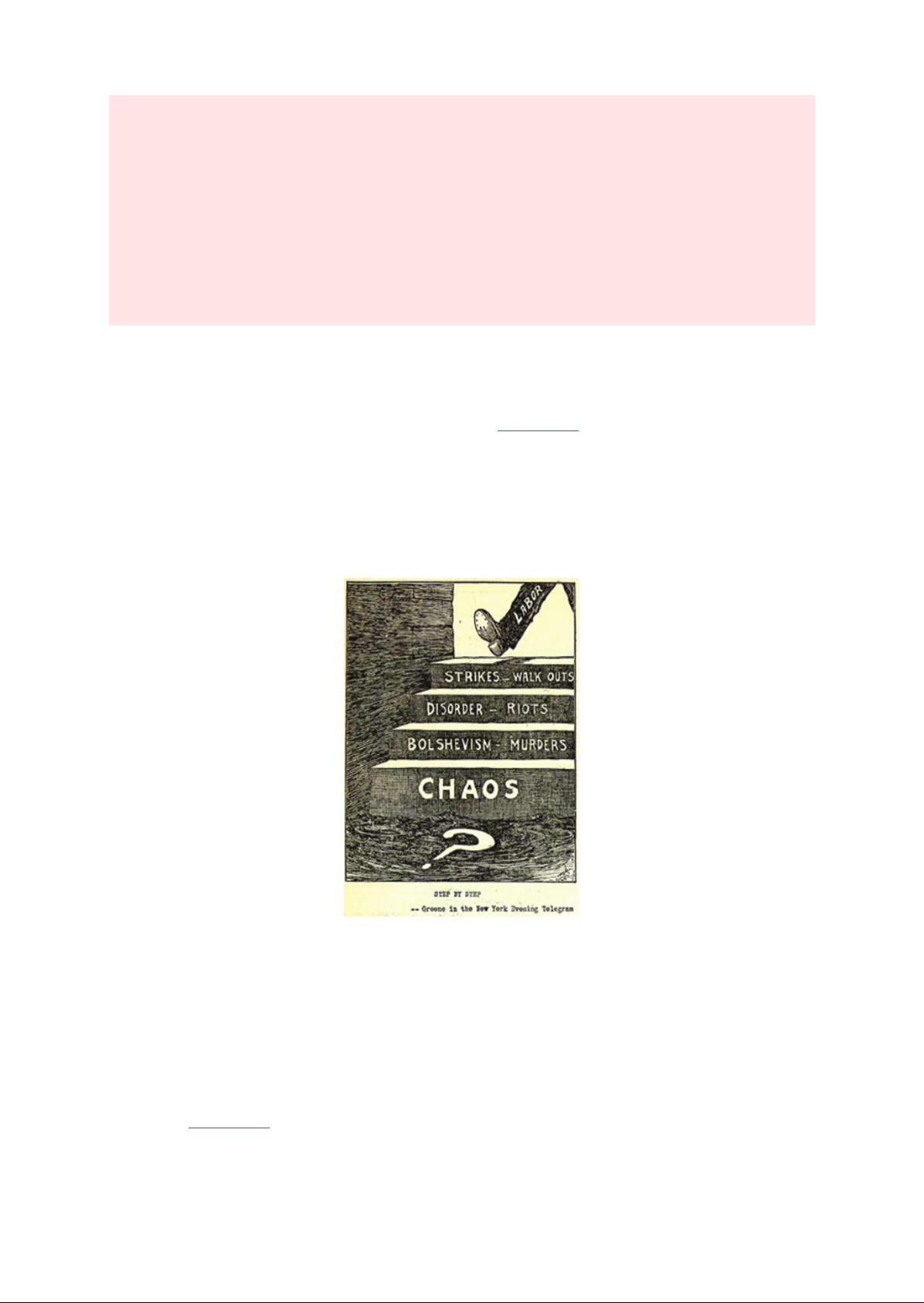

630 23 Americans and the Great War , I reached my in safety , but I knew that that safety would be . I now knew the . I knew too that government and law and order had broken down . I knew that mob law had been substituted in all its and barbarity . I knew that the mobbist cared nothing about the written law and the constitution and I also knew that he had neither the patience nor the intelligence to distinguish between the good and the bad , the and the lawless in my race . From my window , I could see planes circling in . They grew in number and hummed , darted and dipped low . I could hear something like hail falling upon the top of my building . Down East Archer , I saw the old hotel on , its top , and then another and another and another building began to burn from the top . While illness , economic hardship , and racial tensions all came from within , another destabilizing factor arrived from overseas . As revolutionary rhetoric emanating from Bolshevik Russia in 1918 and 1919 , a Red Scare erupted in the United States over fear that Communist sought to overthrow the American government as part of an international revolution ( Figure 2321 ) When investigators uncovered a collection of letter bombs at a New York City post , with recipients that included several federal , state , and local public officials , as well as industrial leaders such as John Rockefeller , fears grew . And when eight additional bombs actually exploded simultaneously on June , 1919 , including one that destroyed the entrance to attorney general Mitchell Palmer house in Washington , the country was convinced that all radicals , no matter what ilk , were to blame . Socialists , Communists , members of the Industrial Workers of the World ( and anarchists They were all threats to be taken down . WALK am Ha in nu ! FIGURE Some Americans feared that labor strikes were the first step on a path that led ultimately to Bolshevik revolutions and chaos . This political cartoon depicts that fear . Private citizens who considered themselves upstanding and loyal Americans , joined by discharged soldiers and sailors , raided radical meeting houses in many major cities , attacking any alleged radicals they found inside . By November 1919 , Palmer new assistant in charge of the Bureau of Investigation , Edgar Hoover , organized nationwide raids on radical headquarters in twelve cities around the country . Subsequent Palmer raids resulted in the arrests of four thousand alleged American radicals who were detained for weeks in overcrowded cells . Almost 250 of those arrested were subsequently deported on board a ship dubbed the Soviet Ark ( Figure 2322 ) Access for free at .