Important Questions for Class 12 History Chapter 8 Peasants, Zamindars and the State (Agrarian Society and the Mughal Empire)

Important Questions for Class 12 History Chapter 8 – 2 Marks Questions

Question 1.

Mention any two steps taken by the Mughals to create the revenue as an administrative apparatus. (All India 2013)

Answer:

The Mughal created the revenue as an administrative apparatus in the following ways:

- The office (daftar) of the diwan was responsible for supervising the fiscal system of the empire.

- The revenue officials and record keepers penetrated the agricultural domain and became decisive agent in shaping agrarian relations.

Question 2.

Write two functions of Jati Panehayat in the 16th and 17th centuries. (Delhi 2008)

Answer:

Following are the two major functions of Jati Panchayat:

- They decided land disputes, and decided whether marriage were being performed according to the norms laid down by caste.

- Jati Panchayats decided civil cases between members of different castes.

Quesiton 3.

Why were women considered as an important resource in agrarian society? Mention two reasons. (HOTS; Delhi 2009)

Answer:

Women were considered as an important resource in the agrarian society due to the following reasons:

- Women were child bearers in agrarian society which was dependent on labour.

- Artisanal tasks such as spinning yarn, sifting and kneading clay for pottery, and embroidery were among the many aspects of production dependent on female labour.

Question 4.

Mention the major crop of Western India during 17th century. How did it come to India. (All India 2010)

Answer:

Maize was the major crop of Western India. It come into India via Africa and Spain and by the 17th century it was being listed as one of the major crops of Western India.

Important Questions for Class 12 History Chapter 8 – 4 Marks Questions

Quesiton 5.

Describe the life of forest dwellers in the Mughal Era. (All India 2015)

or

Describe the life led by the forest dwellers during the Mughal Era in 16th-17th centuries. (Delhi 2014)

Answer:

The life of the forest dwellers during the Mughal Era in 16th-17th centuries can be described in the following ways:

- Forests dwellers were termed as Jangli, but it did not mean an absence of ‘civilisation’.

- The term ‘Jangli’ rather described those whose livelihood came from the gathering of forest products, hunting and shifting agriculture.

- Their activities were mainly season specific. For example, among the Bhils spring was reserved for collecting forest produce, summer for fishing, the monsoon months for cultivation and autumn and winter for hunting.

- For the state, the forest became a subversive place i.e. a place of refuge for troublemakers.

- Forest dwellers supplied elephants for the army.

- In the Mughal period regular hunting expeditions to the forests, often enabled the king to attend personally to the grievances of its inhabitants. ,

Question 6.

How were the subsistence and commercial production closely interwined in an average peasant’s holding during the Mughal period in 16th and 17th centuries? Explain. (HOTS; All India 2014)

Answer:

The agriculture in medieval India was not only for subsistence. The term jins-i-kamil or perfect crops was found in the sources. The subsistence and commercial production were interwined in an average peasant’s holding in the following ways:

- The Mughal state encouraged peasants to produce commercial crops like cotton and sugar for more revenue. These two crops were jins-i-kamil par excellence.

- Cotton was grown over a vast territory, spreading over central India and the Deccan plateau. Bengal was famous for its sugar production.

- Other cash crops included various sorts of oilseeds (mustard) and lentils.

- Many new crops from the different parts of the world reached India. These were maize, tomatoes, potatoes, chillies, pineapple and papaya. It clearly shows that subsistence and commercial production were closely intertwined.

Question 7.

Describe three factors that accounted for the constant expansion of agriculture during 16th and 17th centuries.

(Delhi 2012, 2010)

Answer:

During the 16th and 17th centuries about 85 percent of the population of India lived in villages and agriculture was the main. profession of people. The factors which were responsible for the expansion of agriculture can be explained in the following ways:

The Abundance of Land: The cultivating peasants (asamis) i.e. plough up the fields, marked the limit of each field for identification and demarcation with borders of earth, brick and thorn. There was abundance of land for agriculture.

Availability of labour during Mughal Regime: There was much labour available for the purpose of agriculture, mobility of peasants, which would help in continuous expansion of agricultural land as it increased cultivable land.

Artificial System of Irrigation: Monsoons remained the backbone of Indian agriculture as they are even today. But there were crops which required additional water. Artificial system of irrigation had to be devised for this. Irrigation projects received state support as well. For example e.g. in Northern India, the state undertook digging of new canals and also repaired the old canals.

Question 8.

Describe the condition of an average peasant of North India during the 17th century. (All India 2012)

Answer:

In the Mughal period raiyat, muzarian, kisan or asami were the terms to denote a peasant.

Condition of peasants in North India during 17th century was as follows:

- Overall condition was very ordinary, they had to face economic distress after a femine.

- They had hardly one pair of bullocks and two ploughs. However, most of them even had less than these. In Gujarat, peasants possessing about 6 acre of land were considered to be affluent. In Bengal, 5 acre was the upper limit of an average peasant farm and 10 acres would make a peasant a rich asami.

- Cultivation was based on the principle of individual ownership. Lands of peasants were bought and sold in same way as the lands of other property owners.

- There existed two kinds of peasants: Khud-Kashta They were residents of village in which they had their lands. Pahi-Kashta They were non-resident cultivators, meaning, resident of other village and cultivated in other village. People became Pahi-Kashta either out of a choice (e.g. when terms of revenue were more favourable in other village) or out of compulsion (e.g. forced by economic distress after a famine).

Question 9.

Why were the Jati Panchayats formed during 16th and 17th centuries? Explain their functions and authority. (All India 2011)

Answer:

The Jati Panchayats were formed during 16th and 17th centuries due to the following reasons:

1. The decision of the Panchayat in conflicts between Tower-caste’ peasants and state officials or the local zamindar could vary from case to case.

2. Archival records from Western India-notably Rajasthan and Maharashtra contain petitions presented to the Panchayat complaining about extortionate taxation or the demand for unpaid labour (begar) imposed by the ‘superior’ castes or officials of the state. These included excessive tax demands which, especially in times of drought or other disasters, endangered the peasant’s subsistence.

Thus, Jati Panchayats came into existence. Authorities and functions of Jati Panchayats are as follow:

- These Panchayats wielded considerable power in rural society. In Rajasthan Jati Panchayats arbitrated civil disputes between members of different castes.

- They mediated in contested claims on land.

- They decided whether marriages were performed according to the norms laid down by a particular caste group.

- They also determined who had ritual precedence in village functions, and so on.

- In most cases, except in matters of criminal justice, the state respected the decisions of Jati Panchayats.

Question 10.

Explain why Ain-i Akbari remains an extraordinary document of its times even today. (Delhi 2008)

Answer:

Ain – i Akbari written by Abu’l Fazl remains an extraordinary document of Mughal period even today.

The following are the reasons:

1. It is the third book of Akbar Nama. The Ain is made up of five books, of which the first three books describe the administration, the fourth and fifth books deal with religious, literary cultural tradition and a collection of Akbar’s auspicious sayings. It provided a fascinating glimpses into the structure and organisation of the Mughal empire.

2. It gave us ‘quantitative’ information about its products and people. The value of the Ain’s quantitative evidence is uncontested, where the study of agrarian relations is concerned. Abu’l Fazl adopted completely different stand point from the traditional writers of chronicles by recording the information about the country, its people and products. It contained people, their professions and trades on the imperial establishment and the grandness of the empire. It enables historians to reconstruct the social fabric of India at that time.

Question 11.

Describe the results of India’s overseas trade under the Mughals. (All India 2008)

Answer:

The Mughal Empire was considered as one of the largest territorial empires in Asia which consolidated power and resources during the 16th and 17th centuries. India’s overseas trade under the Mughals flourished due to the following reasons:

- The political stability achieved by the Ming (China) empire, Salavid (Iran) empire and Ottoman (Turkey) empire helped to create vibrant networks of overland trade from China to the Mediterranean Sea.

- Voyages of discovery’ and the opening up of the New World resulted in a large expansion of Asia’s, particularly India’s trade with Europe. It led to a greater geographical diversity of India’s overseas trade. An expansion in the commodity composition of this trade also developed.

- An expanding trade brought in huge amounts of silver bullion to India which was good for India as it did not have natural resources of silver.

- The 16th and 18th century saw a remarkable stability in the availability of silver currency (Rupya) in India.

- It facilitated a large scale expansion of minting coins and circulation of money which helped Mughal state to extract taxes and revenue in cash.

Important Questions for Class 12 History Chapter 8 – 8 Marks Questions

Question 12.

“There was more to rural India than the sedentary agriculture”. Explain the statement in the context of Mughal period. (Delhi 2016)

Answer:

There was more to rural India than the sedentary agriculture. Apart from . intensively cultivated land, there were dense forests or scrubland all over Eastern India, Central India, Northern India, Jharkhand and in Peninsular India down the Western Ghats and the Deccan plateau. The life of the forest dwellers justify the above statement in the following ways:

- Forest dwellers were termed as ‘Jangli’ which did not mean an absence of civilisation.

- The livelihood of forest dwellers included the gathering of forest produce, hunting and shifting agriculture.

- The livelihood of the forest dwellers were largely season specific. For e.g. among the Bhil tribes, spring season was reserved for collecting forest produce, summer for fishing, the monsoon months for cultivation, and autumn and winter for hunting.

- For the state, the forest was regarded as a subversive place i.e. a place of refuge for troublemakers.

- The state required elephants for army. Thus, forest people supplied elephants.

- In the Mughal period, hunting ensured justice to all its subjects, rich and poor. Regular hunting expeditions enabled the emperor to travel extensively and attend grievances of its inhabitants. These were the observations found in Ain-i Akbari.

- New cultural influences also began to penetrate into forested zones. Sufi-saints played a major role in the slow acceptance of Islam among agricultural communities in newly colonised places.

Question 13.

Inspite of the limitations, the Ain-i Akbari remains an extraordinary document of its time. Explain the statement. (HOTS; Delhi 2016)

Answer:

The major sources for the agrarian history of the 16th and early 17th centuries are chronicles and documents from the Mughal court.

One of the most important chronicles was the Ain-i Akbari. Ain was authored by Akbar’s court historian Abu’l Fazl. This text meticulously recorded the arrangements made by the state to ensure cultivation to enable the collection of revenue by the agencies of the state and to regulate the relationship between the state and the zamindars.

Ain-i Akbari was not a mere reproduction of official papers. Abu’l Fazl had worked very carefully to search the authenticity of the documents. He tried to cross-check and verify oral testimonies before incorporating them as facts in the chronicle.

This was why that the text achieved its final form only after having gone through five . revisions. But there are some problems in using the Ain-i Akbari as a source for reconstructing agrarian history of that period. These are:

- We should realise that the Ain-i-Akbari was penned under patronship of the emperor. It was a part of larger royal project of history writing. Its main objective was to depict the Mughal empire under Akbar in such a way as to prove that social harmony was provided by a strong ruling class in the empire.

- The totalling given in the Ain-i Akbari are not thoroughly accurate. We find numerous errors in the totalling.

- Another problem while using the Ain-i Akbari as a source for reconstructing agrarian history is that the quantitative data given in it is of skewed nature.

- Similarly, though the fiscal data from the provinces has been given in detail, sufficient light had not been thrown on vital parameters such as prices and wages of the same areas.

However, it should be kept in mind that despite these limitations, Ain-i-Akbari has its own significance as a historical document. It is a mine of information for us about the Mughal Empire during Akbar’s reign, although it gives us a view, of society from its apex.

The various information compiled in the text, help us significantly in reconstructing the history of the period under consideration.

Question 14.

“The village panchayat during the Mughal period regulated rural society. Explain the statement. (Delhi 2016)

or

Describe caste and rural milieu of Mughal India. How did Jati-Panchayats wield considerable power in the rural society during Mughal period? Clarify. (Delhi 2016)

or

Assess the role played by Panchayats in the villages during Mughal period. (All India 2016)

or

Explain the ways through which Mughal village Panchayats and village headmen regulated rural society. (Delhi 2013)

or

How were the Panchayats formed during 16th and 17th centuries? Explain their functions and authorities (Delhi 2011)

or

Explain the role of Panchayats in the Mughal Rural Indian Society during 16th-17th centuries. (Delhi 2014)

or

Examine the role of Panchayat as the main constituent of the Mughal village community. (Delhi 2015)

Answer:

The Panchayat and villagemen occupied a significant place in rural society during the period of the 16th and 17th centuries. They played an important role in regulating the rural society.

Generally the Village Panchayat was an assembly of important and respected elders of the village having hereditary rights over their property Every Panchayat was headed by a headman who was known as Muqaddam or Mandal. The headman could hold his office as long as he enjoyed the confidence of the village elders. He had to lose his position if he failed to win the confidence of the elders. The Panchayat had its own funds. All the villagers contributed to a common financial pool. All expenditures of the Panchayat were met from these funds. The functions of Panchayat are:

1. The Panchayat was responsible for the administration of the village. All the functions such as security, health, and cleanliness, primary education, law and order, irrigation, construction work and making arrangements for the moral and religious upliftment of the masses were performed by the Panchayat.

One of the main function of the Panchayat was to keep accounts of the income and expenditure of the village. It used to accomplish this task with the help of the accountant or patwari of the Panchayat.

2. The most important function of the Panchayat in medieval India was to regulate the rural society The Panchayat endeavoured to ensure that the various communities inhabiting the village were up holding their caste limits and were following their caste norms as well. Thus, overseeing the conduct of the members of the village community in order to prevent any offence against their caste w’as an important duty of the village headman or mandal.

In addition to the village Panchayat, each caste or jati in the village had its own Jati Panchayat. The caste Panchayat protected the rights and interests of its members and raised voice against any injustice caused to them. The members of a particular caste could complain to their Panchayat in case the members of a superior caste or state officials forced them to pay taxes or to perform unpaid labour.

Villagers regarded the village Panchayat as the court of appeal that would ensure that the state carried out its moral obligations and guaranteed justice. The decision of the Panchayat in relation to conflicts between ‘lower caste’ peasants and state officials or lower zamindars could vary from case to case. Sometimes panchayat suggested to compromise and in cases where reconciliation failed, peasants took their own decisions.

3. The Panchayats had the authority to levy fines and inflict more serious forms of punishment like expulsion from the community. These meant that the person was forced to leave the village and became an outcaste and he lost the right to practise his profession. Such a measure was taken on a violation of caste norms.

Question 15.

“Revenue was the economic mainstay of the Mughal Empire”. Explain the statement in the context of agriculture and trade. (Delhi 2016)

Answer:

Revenue was the economic mainstay of the Mughal Empire. This can be explained in the following ways:

- It was vital for the state to create an administrative apparatus to ensure control over agricultural production and to fix and collect revenues from the entire empire.

- The administrative apparatus included the office (daftar) of the diwan who was responsible for supervising the fiscal system of the empire. The revenue officials and record keepers became decisive agents in shaping agrarian relations.

- The Mughal state tried to first acquire specific information about the extent of the agricultural lands in the empire and what these lands produced before fixing the burden of taxes on people.

- The land revenue arrangements consisted of two stages-first assessment and then actual collection. The ‘Jama’ was the amount assessed, and the hasil was the amount collected by the cultivators.

- Akbar decreed that cultivators could pay in cash or in kinds. While fixing revenue, the attempt of the state was to maximise its claims. Both cultivated and cultivable lands were measured in each province.

- In the field of trade, a huge amounts of silver bullion from Europe came to India which was good for our country, as India did not have natural resources of silver. It resulted a remarkable stability in the availability of metal currency i.e. silver rupya. It also facilitated an unprecedented expansion of minting of coins and the circulation in the economy. It helped the Mughal state to extract taxes and revenues in cash.

Question 16.

Analyse the role of zamindars during the Mughal period. (HOTS; All India 2016, 2014, 2013)

Answer:

The zamindars in the Mughal period were the class of those people who lived off agriculture but did not take part directly in the processes of agricultural production. Role of zamindars during the Mughal period are:

- They were landed proprietors who enjoyed certain social and economic privileges by virtue of their superior status in rural society.

- The factor of caste hierarchy played a significant role in the elevated status of zamindars. Another factor was that, they performed certain services (Khidmat) for the state.

- The zamindars had extensive personal lands, known as milkiyat. These lands w’ere cultivated with the help of hired labour for the private use of zamindars. The zamindars had the right to sell or mortgage these lands.

- The zamindars could often collect

revenue on behalf of the state, a service for which they were compensated financially. - The zamindars had fortresses and armed military resources which comprised of cavalry, artillery and infantry.

- If we visualise social relations in the Mughal countryside as a pyramid, zamindars constituted its very narrow apex. Abu’l Fazal said that an upper-caste, Brahmana-Rajput combine had already established firm control over rural society. However, Muslim zamindars were also present at that time.

- The dispossession of weaker people by a powerful military chieftain was a way of expanding a zamindari system. State did not support this aggression unless the zamindar had an imperial order (sanad).

- Sometimes in the slow processes of zamindari consolidation people belonging to the relatively lower castes entered the rank of zamindars. For e.g. peasant-pastoralists (like the Sadgops) carved out powerful zamindaris in areas of Central and South-Western Bengal.

- Zamindars spear headed the colonisation of agricultural land and helped in setting cultivators by providing them means of cultivation, cash, loan, etc.

The buying and selling by zamindars accelerated the process of monetisation in the country side. They sold the produce from their milkiyat lands. They often established markets (haats) to which peasants came to sell their produce. - Although, zamindars were an exploitative class, their relationship with the peasantry had an element of reciprocity, paternalism and patronage.

- Two views supported this fact. Firstly, the Bhakti saints who were the strong critic of casteism and other forms of oppression, did not portray the zamindars as exploiters of the peasantry. Secondly in a large number of agrarian uprisings in the 17th century, zamindars often received the support of the peasantry in their struggle against the state.

Question 17.

Examine the status and role played by women in the agrarian society during Mughal period. All India 2016 or

Explain the role of women in the agrarian society in Mughal India (Delhi 2008)

Answer:

Women played an important role in Indian agrarian society during the medieval period. Women belonging to peasant families participated actively in agricultural produce and worked shoulder to shoulder with men in the field.

Status and role of women were as follows:

1. The work of tilling and ploughing the fields was performed by men. The women particularly did the work of sowing, weeding and harvesting. They also extended their cooperation in threshing and winnowing the harvest. In fact, the labour and resources of the entire household had become the basis of production with the growth of nucleated village and expansion in individual peasant fanning during the 16th and 17th centuries. Therefore, it became quite difficult to draw a divisive line between the spheres of works for women and men.

2. Some aspects of production especially, artisanal tasks like spinning yarn, sifting and kneading clay for pottery and embroidery, etc were thoroughly dependent on female labour. It seems that the demand of women’s labour started growing with the commercialisation of the product. The peasant and artisan women worked in the fields, went to the house of their employers or to the markets, if necessary.

3. It is worth mentioning that as the women were child bearers in a society dependent on labour, they were regarded as an important resource in agrarian society. But because of frequent pregnancies, malnutrition and death during child birth, the mortality rate among women was very high. Thus, the number of the married women or wives in the society became less. Thus, marriages in many rural communities required the payment of bride price rather than dowry.

4. Instances from the contemporary sources suggest that several Hindu and Muslim women were inherited by zamindaris. They could sell or mortgage those zamindars. We find mention of women zamindars in Bengal and Rajasthan.

5. However, it should be kept in mind that the biases related to women’s biological functions still remained in existence.

For instance, in Western India, menstruating women could not touch the plough or potter’s wheel. In fact, they were not allowed to do so. Similarly, in Bengal, the menstruating women were not allowed to enter the groves where betel leaves (pan) were grown.

6. Women were kept under strict control by the male members of the family and the community. There was strict punishment for women if they suspected infidelity. But male infidelity was not always punished. Documents from Rajasthan, Gujarat and Maharashtra showed that record of petition sent by women to seek justice.

Question 18.

Explain the organisation of the administration and army during the rule of Akbar as given in ‘Ain-i Akbari’. (All India 2012)

Answer:

Ain-i Akbari consists of 5 books or daftars. The first three books of the Ain are about the description of the administration. Akbar was a great administrator and viewed it as the central point of his policies in administration. It is considered as a rich treasure of various information regarding the Mughal Empire during the rule of Akbar.

The following points can be the highlights:

The Manzil-Abadi:

The first book among 5 describes the royal household and its maintenance.

Sipah-Abadi:

The second book gives the detailed account of civil and military administration and the establishment of servants. It includes notices and short biographical sketches of imperial officials, learned men, poets and artists.

Mulk-Abadi:

The third book gives the fiscal polices of Mughal rule. It gives the detailed information on revenue rates alongwith the account of the 12 provinces. It also comprises of statistical figures having information on geographic, topographic and economic details of all subas and their administrative and fiscal divisions (Sarkars, Paraganas and Mahals), total measured area and assessed revenue (Jama).

Ain also provides a detailed picture of the Sarkars below the Suba. It does give a table data which has 8 columns with the following information:

- Parganat/Mahal

- Qila/(Forts)

- Arazi and Zamin-i-Paimuda (measured area)

- Naqdi, revenue assessed in cash

- Suyurghal, grants of revenue in charity

- Zamindars and

Columns 7 and 8 contain details of the castes of these zamindars, and their troops including their horsemen, foot soldiers and elephants.

Organisation of the Army during Akbar

- It consisted mainly three parts

- The troops provided by the Rajas or chiefs who were bound to supply military help to the king.

- The contingents of the Mansabdars.

- Emperor’s standing Army.

- There were two groups of soldiers to serve as bodyguards and were highly paid. These were known as Dakhilis and Ahdis.

- The imperial army consists of

- The infantry.

- The artillery

- The Cavalry

- The elephant corps

- The Navy

- The cavalry was considered as the main power centre of the army. Though the Mughal Empire is less known about naval power but Akbar had a naval department.

Important Questions for Class 12 History Chapter 8 Source Based Question

Quesiton 19.

The Ain on land revenue collection:

Let him (the amil-guzar) not make it a practice of taking only in cash but also in kind. The latter is effected in several ways. First, kankut: in the Hindi language kan signifies grain, and kut, estimates… If any doubts arise, the crops should be cut and estimated in three lots, the good, the middling and the inferior, and the hesitation

should be removed. Often, too, the land taken by appraisement, gives a sufficiently accurate return.

Secondly, batai, also called bhaoli, the crops are reaped and stacked and divided by agreement in the presence of the parties. But in this case several intelligent inspectors are required; otherwise, the evil-minded and false are given to deception. Thirdly, khet-batai, when they divide the fields after they are sown. Fourthly, land batai, after cutting the grain, they form it in heaps and divide it among themselves, and each takes his share home and turns it to profit.

- Explain the kankut system of land revenue.

- How was the land revenue assessed in the case of batai or bhaoli?

- Do you think that the land revenue system of the Mughals was flexible? (All India 2017)

Answer:

1. I think Kankut was a better method. The term ‘Kankut’ is a combination of two terms:

- Kan which signifies grain and

- Kut signifies estimates.

If any doubt arose, the crops were cut and estimated in three lots, the good, the middling and the inferior. Thus, the peasant could give tax in kinds not in cash.

2. In the case of batai or bhaoli the crops are reaped and stacked and divided by agreement in the presence of the parties. But in this case several intelligent inspectors are required; otherwise the mediator who are evil-minded are given to deception.

3. Yes, the land revenue system in the period of Mughal was flexible. As there are four kinds of revenue systems due to which revenue can be collected easily.

Question 20.

Classification of Lands under Akbar:

The following is a listing of criteria of classification excerpt from the Ain. The Emperor Akbar in his profound sagacity classified the lands and fixed a different revenue to be paid by each.

Polaj is a land which is annually cultivated for each crop in succession and is never allowed to lie fallow.

Parauti is land left out of cultivation for a time that it may recover its strength. Chachar is land that has lain fallow for 3 or 4 years. Banjar is land uncultivated for 5 years and more. Of the first two kinds of land, there are 3 classes, good, middling, and bad. They add together the produce of each sort, and the third of this represents the medium produce, one-third part of which is exacted as the Royal dues.

- Explain briefly the classification of lands by Akbar.

- How the revenue was fixed for the first two type of lands?

- Suggest some other way as you feel better. (Delhi 2010)

Answer:

1. Emperor Akbar classified lands in the following ways:

- Polaj: The land which is annually cultivated for each crop in succession and is never allowed to lie fallow.

- Parauti: The land is left out for cultivation for a time that it may recover its strength.

- Chachar: The land that has lain fallow for 3 or 4 years.

- Banjar: The land is uncultivated for 5 years and more.

2. The first two types of lands were divided into three classes, viz. good, middling and bad. The produced of each sort was added together and the third of this represents the medium produce, on-third part of which is exacted as the Royal dues.

3. I think Kankut was a better method. The term ‘Kankut’ is a combination of two terms:

- Kan which signifies grain and

- Kut signifies estimates.

If any doubt arose, the crops were cut and estimated in three lots, the good, the middling and the inferior. Thus, the peasant could give tax in kinds not in cash.

Important Questions for Class 12 History Chapter 8 Map Based Question

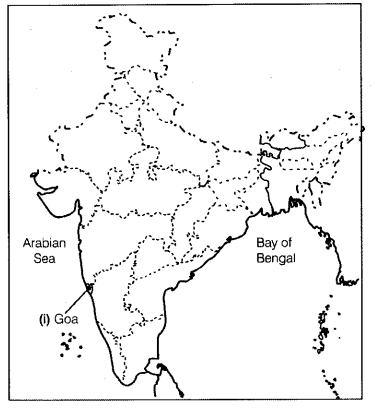

Question 21.

On the given political outline map of India, locate and label the following appropriately.

(i) Goa-A territory under the Mughals.

Answer:

Important Questions for Class 12 History Chapter 8 Value Based Questions

Question 22.

1. Explain the various sources to know about the rural society during the Mughal period.

2. Explain the technology used by the peasants for the cultivation during the same period. (Delhi 2016)

Answer:

1. The major source for the history of agrarian society of the 16th and 17th centuries are chronicles and documents from Mughal court. The authors of Mughal chronicles were courtiers. The histories they wrote focused on events centred on the ruler, his family, the court, nobles, war and administrative arrangements.

Some of the important chronicles were Akbar Nama, Shahjahan Nama, Alamgir Nama, etc. The most important Chronicle was Ain-i Akbari which was the third book of Akbar nama.

Ain-i Akbari was written by Akbar’s court hisorian Abu’l Fazl. It meticulously recorded the arrangements made by the state to ensure cultivation, to enable the collection of revenue by the agencies of the state and to regulate the relationship between the state and the zamindars.

The main purpose of the Ain was to present a vision of Akbar’s empire where social harmony was provided by the ruling class. Abu’l Fazl thought that any revolt against the Mughal rulers was predestined to fail.

Whatever we know from the Ain about peasants remains a view from the top. The extensive records of the East India

Company provided us with important descriptions of the agrarian relations in Eastern India. All these sources record instances of conflicts between peasants, zamindars and the state. In the process, they give us an insight into peasant’s perception and expectations from the state authority.

2. During the Mughal peirod the terms raiyat, muzarian were used to denote the peasants. Cultivation was based on the principle of individual ownership. Monsoon is regarded as the backbone of Indian agriculture. But some crops required additional water. Artificial system of irrigation thus needed for it. Technologies used by the peasants for the cultivation were:

- Sometimes people used buckets and wheels to irrigate the land.

- Irrigation projects got state support. In Northern India, the state undertook digging of new canals (nahr or nala) and also repaired old ones, e.g. Shahnahar in Punjab during Shah Jahan’s reign.

- Peasants also used technologies that generally harnessed cattle energy.

The wooden plough was light and easily assembled with an iron tip or coulter. It did not make deep furrows, which preserved the moisture better during the intensely hot months. - A drill, pulled by a pair of giant oxen was used to plant seeds. But broadcasting was the most prevalent method during that time. Hoeing and weeding were done simultaneously using a narrow iron blade with a small wooden handle.

Question 23.

Read the following passage and answer the question that follows.

Women were considered an important resource in agrarian society also because they were child bearers in a society dependent on labour. At the same time high mortality rates among women – owing to malnutrition, frequent pregnancies, death during childbirth-often meant a shortage of wives. This led to the emergence of social customs in peasant and artisan communities that were distinct from those prevalent among elite groups. Marriages in many rural communities required the payment of bride-price rather than dowry to the bride’s family. Remarriage was considered legitimate both among divorced and widowed women.

The importance attached to women as a reproductive force also meant that the fear of losing control over them was great. According to established social norms, the household was headed by a male. Thus, women were kept under strict control by the male members of the family and the community. They could inflict draconian punishments if they suspected infidelity on the part of women.

1. Discuss the status of women in agrarian society in 17th century.

Answer:

1. In the 17th century in agrarian society women were considered an important resource, because they were child-bearers in a society dependent on labour.

At the same time, high mortality rates among women owing to malnutrition, frequent pregnancies, death during child-birth often meant a shortage of wives. This led to the emergence of new social customs in peasant and artisan communities which were never before. For e.g. payment of bride-price rather than dowry and remarriage of divorced and widowed women.

None the less women were considered as an important reproductive source, there was a great fear of losing control over them by male society. According to established social norms, the household was headed by a male. Thus, women were kept under strict control by the male members of the family and the community. They could inflict draconian punishments if they suspected infidelity on the part of women. While male infidelity was not always punished due to gender biasness. Thus, the status of women in agrarian society was some what the same as today.

Question 24.

Read the following passage and answer the question that follows.

Although there can be little doubt that zamindars were an exploitative class, their relationship with the peasantry has an element of reciprocity, paternalism and patronage.

Two aspects reinforce this view. First, the bhakti saints, who eloquently condemned caste-based and other forms of oppression, did not portray the zamindars (or, interestingly, the moneylender) as exploiters or oppressors of the peasantry.

Usually it was the revenue official of the state who was the object of their ire.

Second, in a large number of agrarian uprisings which erupted in north India in the seventeenth century, zamindars often received the support of the peasantry in their struggle against the state.

1. Which aspects highlight the view that zamindars were not exploitative class in the period of the Mughals?

Answer:

There are two aspects which reinforce the view that zamindars were not an exploitative class, rather their relationship with the peasantry had an element of reciprocity, paternalism and patronage. These aspects are as follow:

- The first aspect is that, the bhakti saints, who eloquently condemned caste-based and other forms of oppression did not portray the zamindars (or, interestingly, the moneylenders) as exploiters or oppressors of the peasantry. Usually it was the revenue official of the state who was the object of their ire.

- Second aspect explains that, in a large number of agrarian uprisings which erupted in north India in the 17th century, zamindars often received the support of the peasantry in their struggle against the state.